Brookings’ Faulty Defense of Transparency

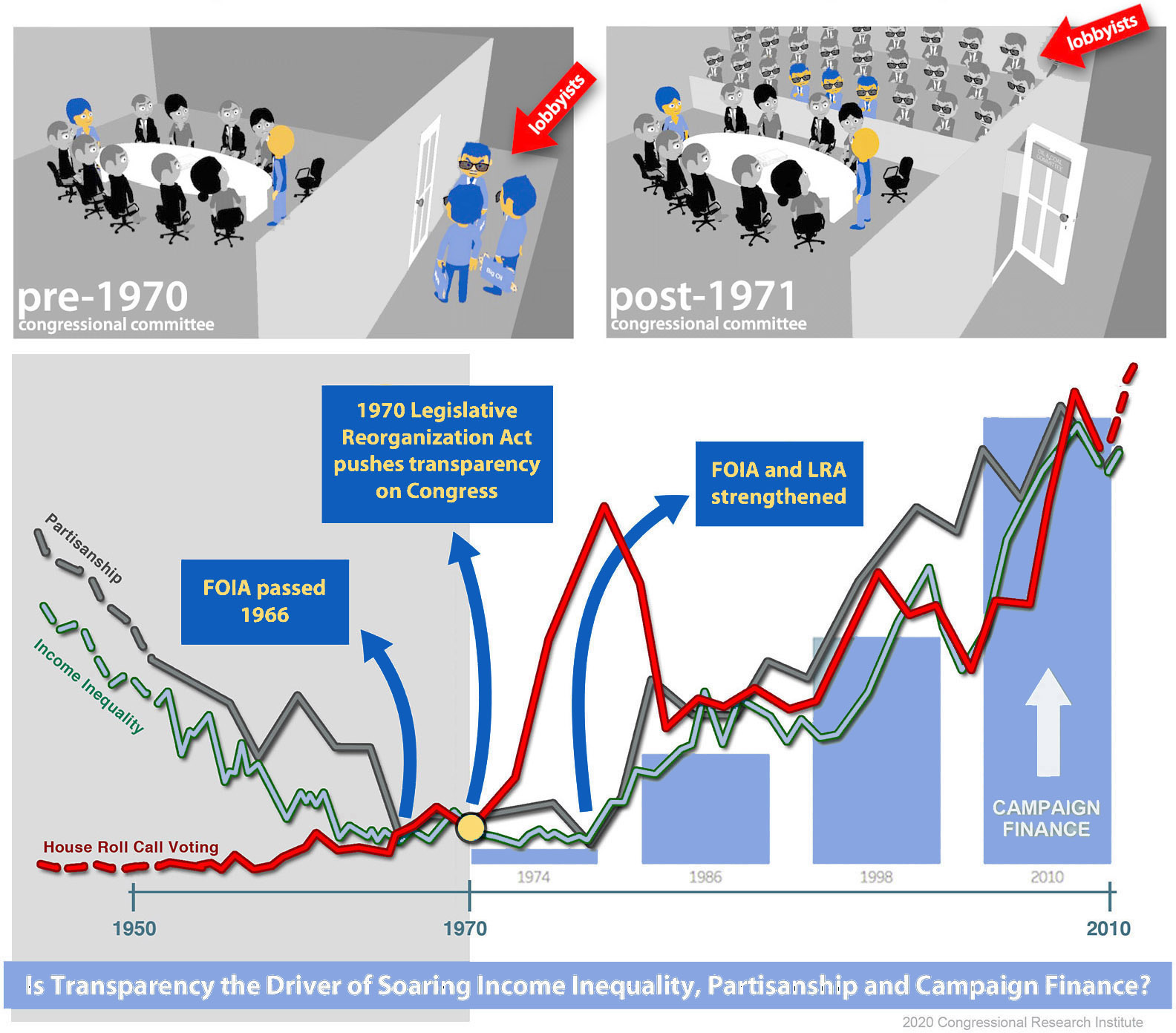

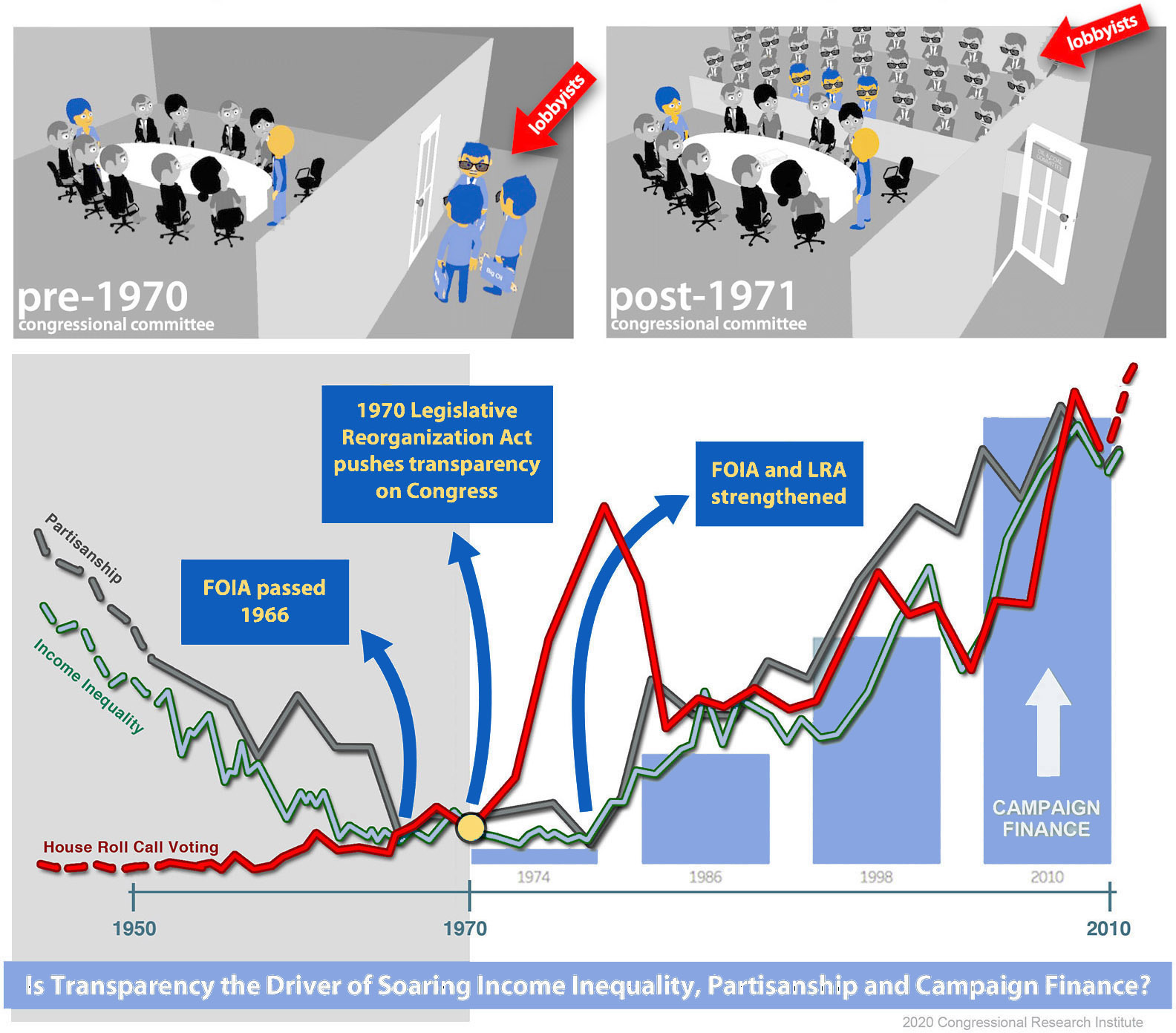

By overlooking one of two major congressional reforms, the 1970 Legislative Reorganization Act, Gary D. Bass, Danielle Brian and Norman Eisen publish mistaken claims about the benefits of sunshine. In November 2014, they authored a Brookings’ report titled ‘Why The Critics of Transparency are Wrong.’ Claiming that congressional transparency surged in 1986 (not in 1971 as the LRA mandated), they come to flawed conclusions.

By David King & James G. D’Angelo – November 2017 (updated 2020)

DRAFT

A number of commentators and academics have recently made the attention-grabbing assertion that excessive openness and transparency are one of the causes of our country’s governance woes.– Bass, Brian & Eisen 2014

A Fundamental Mistake

Gary D. Bass, Danielle Brian and Norman Eisen (B, B & E) are fervent advocates of government transparency. And so in a 2014 Brookings report, they take on a handful of scholars and journalists who had suggested in prior work that perhaps congressional transparency might not be as beneficial as once thought. And while the piece is now somewhat dated it is notable for two reasons. One, it is one of the only ‘academic’ papers in support of legislative transparency. Two, in a recent 2017 talk at Harvard moderated by pro-transparency advocate Archon Fung, Norm Eisen reaffirmed the alleged authenticity of this 2014 report. In the talk, Eisen referred to his paper as the essential 'data' that proves the benefits of transparency in Congress. The trouble is, the Brookings piece is deeply and fatally flawed.

Upon publication, the paper received immediate applause (from the legions of pro-transparency advocates) as well as important pushback. Dr. Sarah Binder, a political scientist at George Washington University, and one of those attacked by B, B & E, published her pushback the following month. In it, Binder took B, B & E to task on their notion that transparency improves negotiations. She claimed that that secrecy (as James Madison and others have long suggested) limits partisanship and can improve negotiations. She writes:

Our point is simply that transparency entails trade-offs, imposing direct costs on successful deal-making. This is especially true given today’s exceptionally polarized and competitive political parties and given the information environment in which lawmakers work. As we observed in our piece, greater public attention to Congress today combined with polarized parties increases the incentives of lawmakers to adhere to party messages.

Surprisingly however, and perhaps in the heat of the response, Binder does not notice the fundamental error of B, B & E’s paper. Central to B, B & E’s argument is their mistaken notion that Congress went through a massive increase in transparency in the 1980s. The authors use this date as their rock. Focusing on 1986 in particular, they go on to show that little change in political outcomes can be observed in this period. Yet they somehow overlook one of the two most important laws in congressional history – the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970.

Signed into law by Richard Nixon on October 26th, 1970, the LRA is also the most important transparency law in congressional history. Enacted just months later (January 3rd, 1971), it pushed both congressional committees and congressional voting into the sunshine, 15 years before B, B & E claim.

The changes surrounding the 1970 LRA

The changes surrounding the 1970 LRA

But, how is this oversight possible? Gary D. Bass is a professor of public policy at Georgetown, Danielle Brian has spent twenty years working on transparency initiatives and Norm Eisen is a widely followed and celebrated lawyer who has worked in government, pushing transparency initiatives for decades. Yet none of these ‘insiders’ appear to be familiar with one of only two major congressional reforms, the 1970 LRA (the other LRA took place in 1946).

Dozens of scholars point to the LRA as problematic. With hundreds of historical citations suggesting that congressional transparency overwhelmingly benefits lobbyists and special interests. Journalist Fareed Zakaria, summed up the sitution in his 2003 bestseller, The Future of Freedom:

Among the most consequential reforms of the 1970s was the move toward open committee meetings and recorded votes. Committee chairs used to run meetings at which legislation was “marked up” behind closed doors. Only members and a handful of senior staff were present. By 1973 not only were the meetings open to anyone, but every vote was formally recorded. Before this, in voting on amendments members would walk down aisles for the ayes and nays. The final count would be recorded but not the stand of each individual member. Now each member has to vote publicly on every amendment. The purpose of these changes was to make Congress more open and responsive. And so it has become – to money, lobbyists, and special interests.

As Zakaria states, the 1970 LRA mandated the opening of all the once closed committees to the public and insisted on the publication of the vast majority of congressional votes. Thus, almost overnight, the US Congress switched from being one of the most closed institutions in history to one of the most open.

Bass, Brian & Eisen’s Historical Mistake

Bass, Brian & Eisen’s Historical Mistake

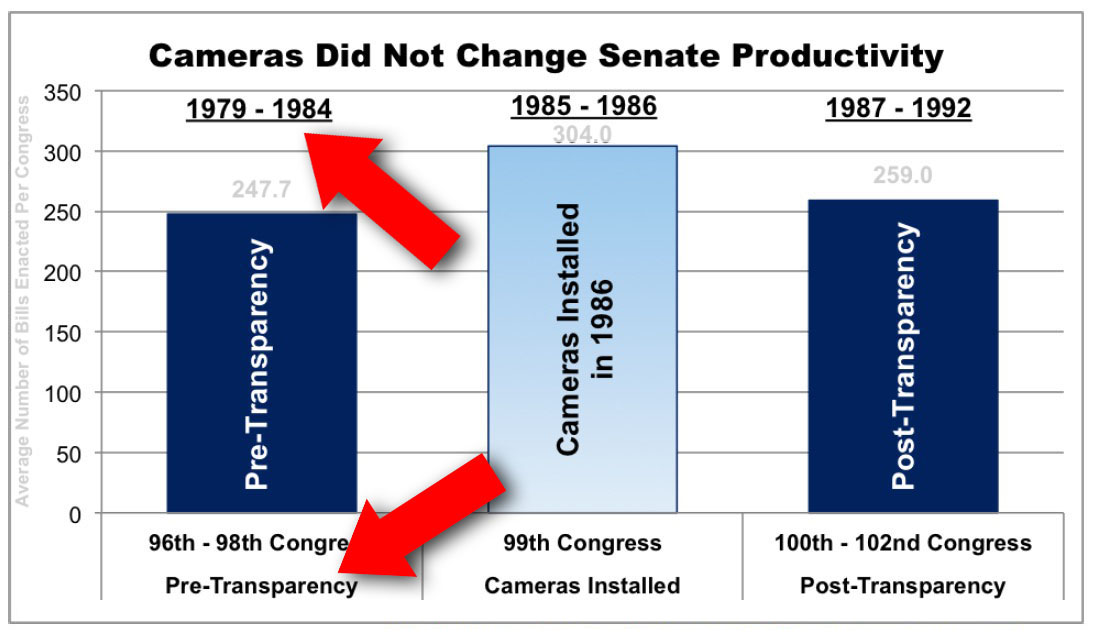

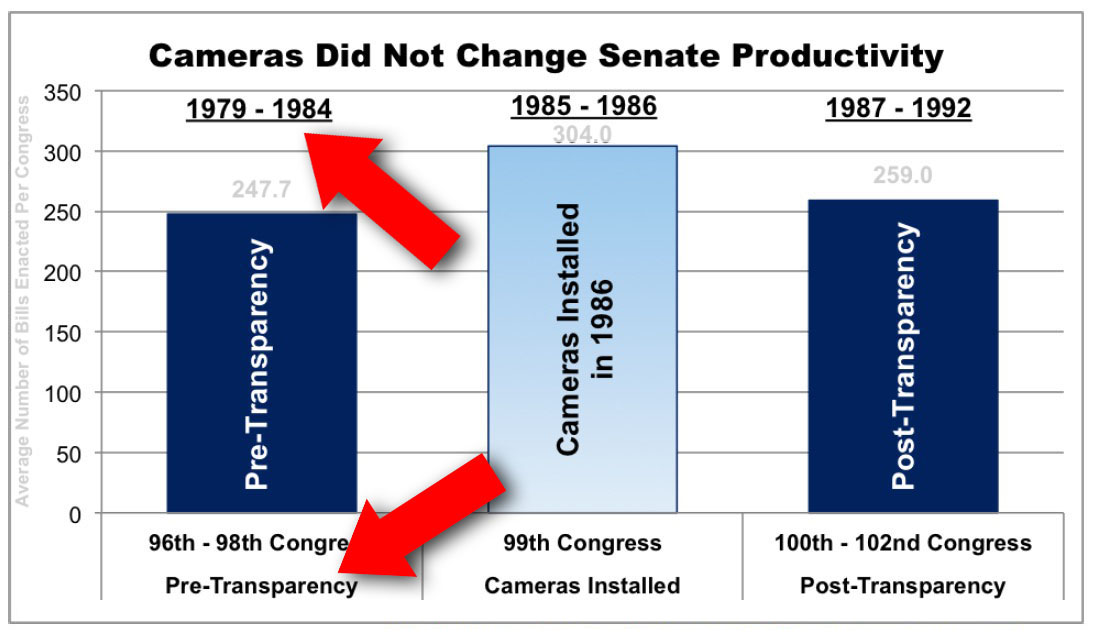

Somehow, B, B & E overlooked this fundamental change. And nothing makes this clearer then this graphic from their paper (above). In this image, one can see that the authors mistakenly cite the introduction of television cameras (and CSPAN) as the beginning of congressional transparency. They claim that the pre-transparency period (red arrows) is from 1979-1984, and the post-transparency period is from 1987 onward, mistakingly pointing to the beginnings of congressional transparency 15 years after it occurred. So yes, the Senate began televising in 1986, but the move to transparency was over a decade earlier. This, of course, negates their arguments that follow, as they build entirely around this mistaken 1986 date. And their subsequent mistakes make sense. If one looks for stark patterns or elbows in congressional behavior in the periods surrounding 1986, as they do, they are likely to come up with little or nothing. But that is all they offer. And it is this lack of significant change around 1986 that forms the core of their flawed conclusions.

It is striking that these the authors could have made such an oversight. But it is just as striking that this error didn’t grab the attention of their editors or other scholars at Brookings who read the paper. This might be excusable if the LRA were just a mere rule change, but the 1970 Act was in the works for over a decade, and it remains as one of two major reorganizations of Congress. Futher, the authors have somehow managed to avoid the many scholars (like Zakaria) who have pointed to the LRA as problematic. Note: To our knowledge, the only notable holdout with respect to the LRA is a young academic named Lee Drutman, and we discuss his particular case here.

Finally, B, B & E make another error of timeline in the same paper. Writing in 2014, they precede the above argument by claiming that “It is true that over the past fifteen years or so, Congress has decided on its own to become a more open institution.” And so here they are hinting that Congress began its true march toward sunshine, not in the mid-late 1980s (as they argue in the graph above), but just before the year 2000, further magnifying their error by another 15 years. In their enthusiasm to debunk calls for secrecy, they somehow overlook the 1970 LRA, the work of dozens of scholars as well as the Constitution.

–+–

Note: For the past five years we have reached out to the authors of the Brookings paper and have yet to receive a response. For more on this topic, see our 2019 piece in Foreign Affairs or browse all the links and citations on this site.

Bass, Brian & Eisen’s Historical Mistake