1250+ Academic Citations

The Pitfalls of

Congressional Transparency

How Lobbyists Thrive on Government Transparency

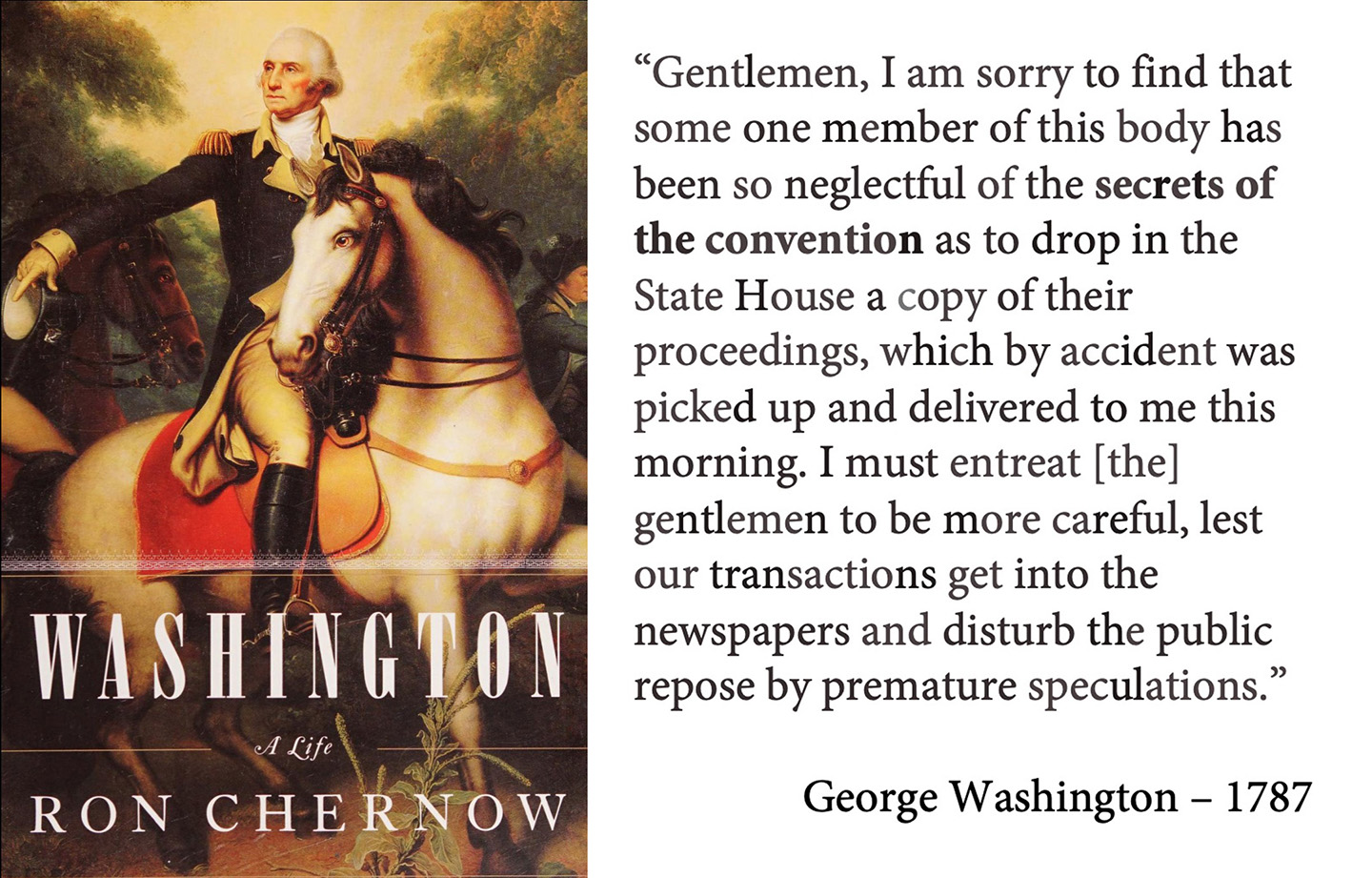

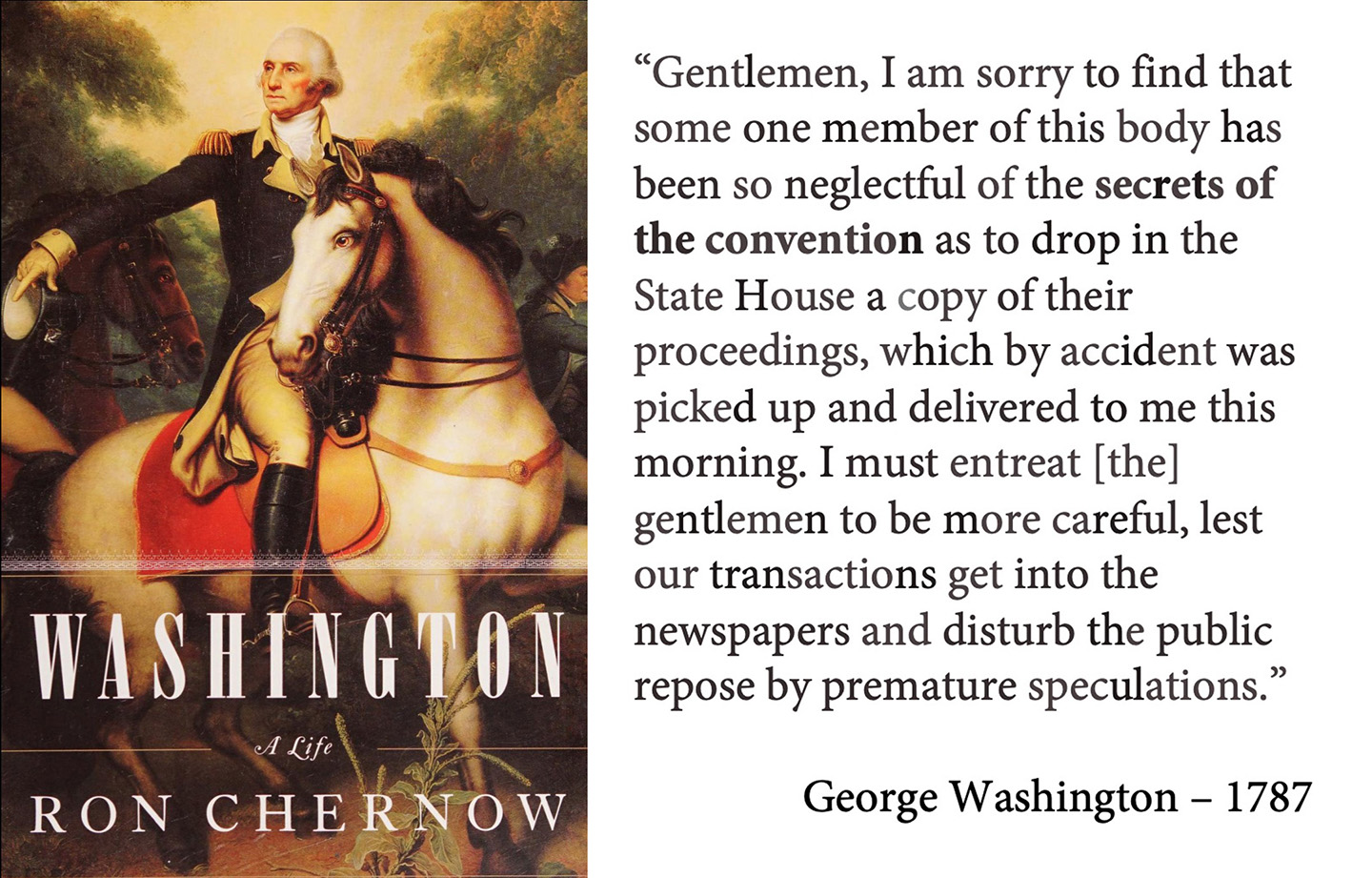

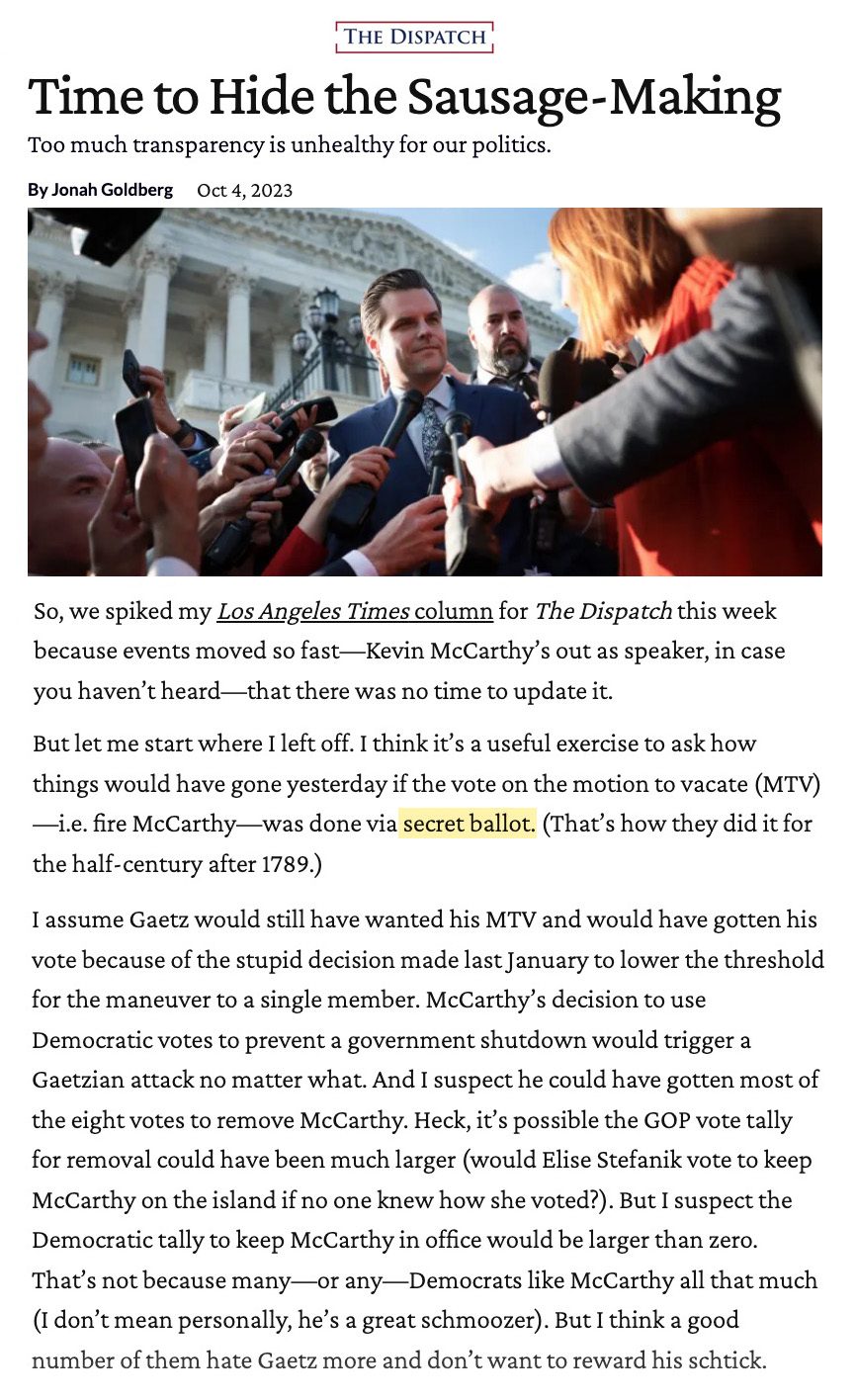

When drafting legislation, the Founding Fathers relied on secrecy. They wrote the Constitution and Bill of Rights in abject secrecy. This was no accident. As the following citations show, greater transparency has long been known to degrade the legislative process and provide benefits to powerful factions (lobbyists, partisan groups, and monied special interests).

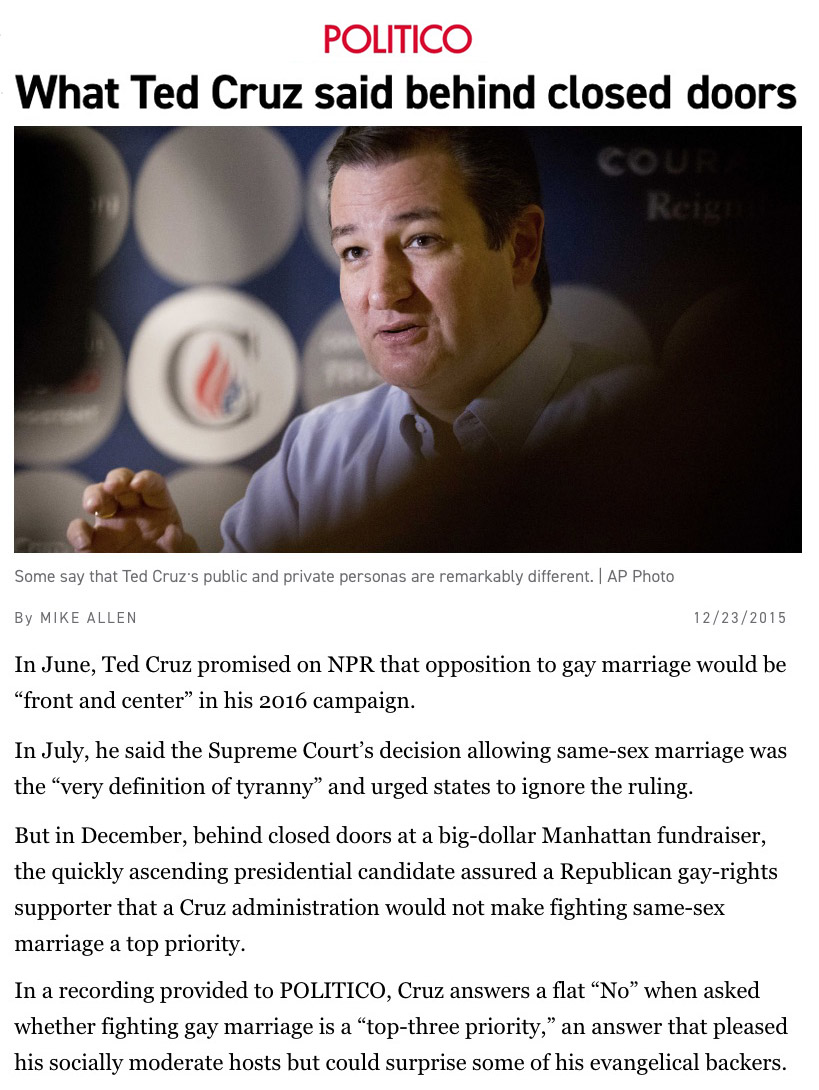

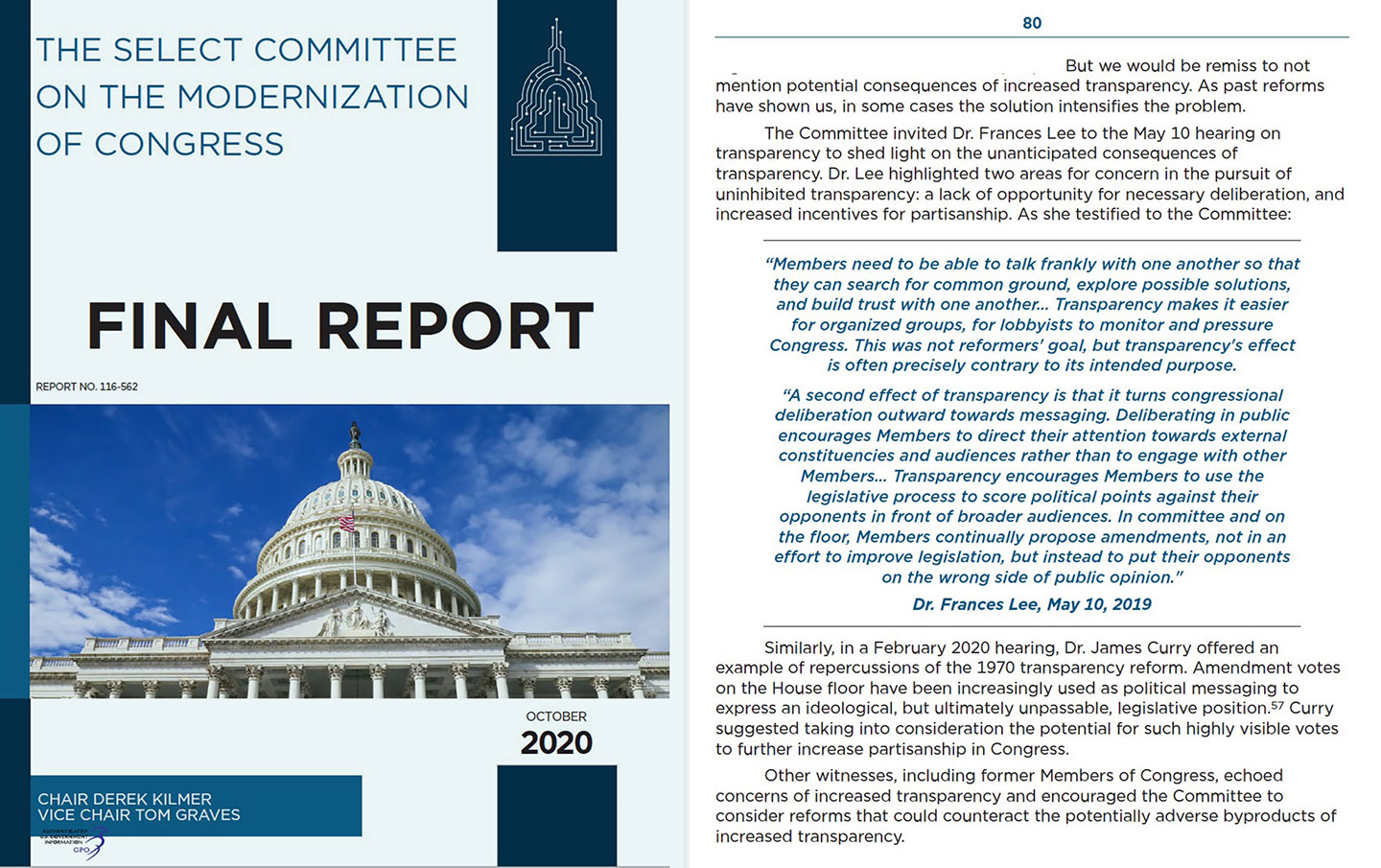

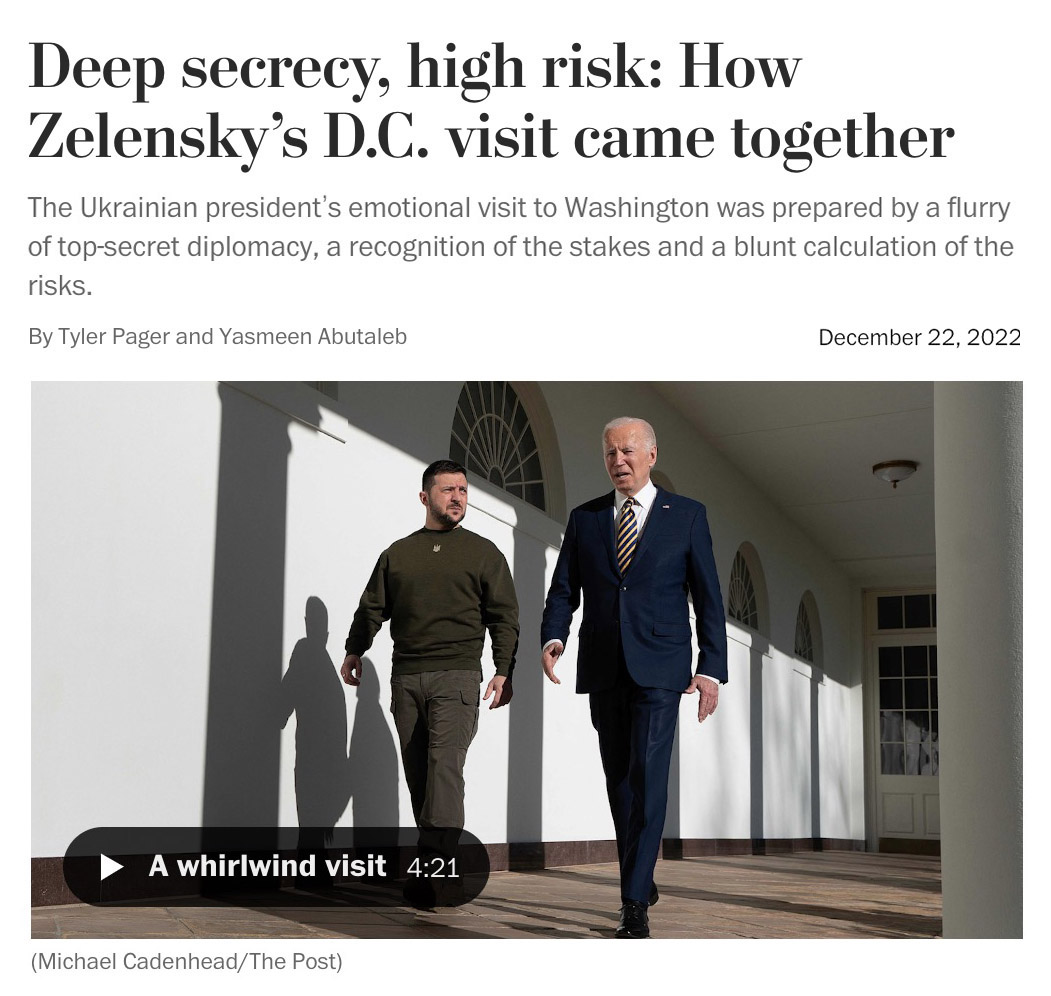

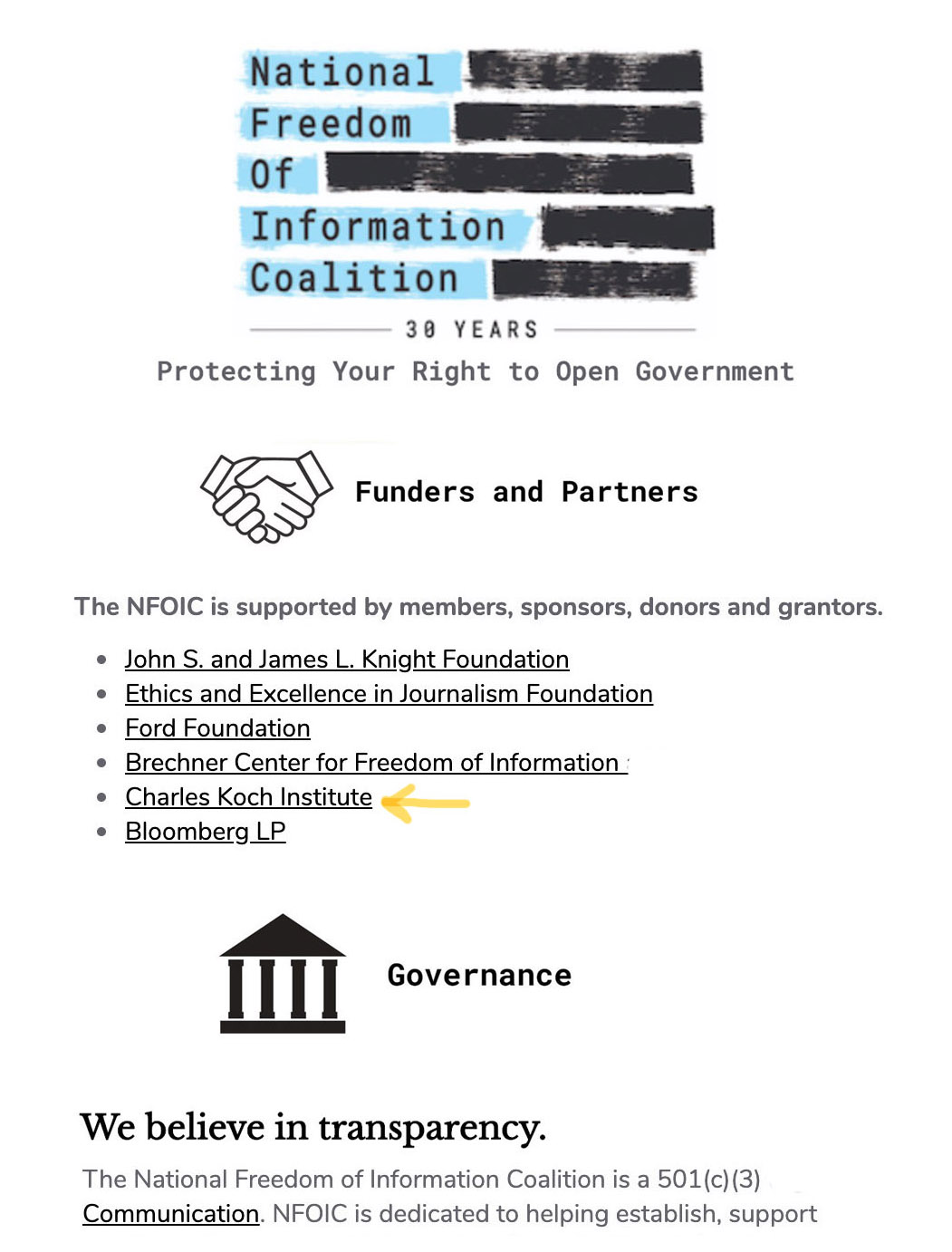

Today, despite decades of pro-transparency funding by billionaires like Charles Koch, Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates, the tide is turning. In March 2022, Joe Biden became the first U.S. President to suggest the benefits of secret ballots in legislatures. In 2021, Republican Senator Ben Sasse and Democrat Chuck Schumer were the first two U.S. Senators to suggest the same. In 2019 Princeton’s Frances Lee became the first scholar to present the benefits of secrecy to the House of Representatives. She declared that transparency benefits lobbyists, destroys accountability and drives both partisanship and chaos. The members of the committee agreed, becoming also the first sitting members of the House to concede this point. In 2020, scholar James Curry presented similar findings.

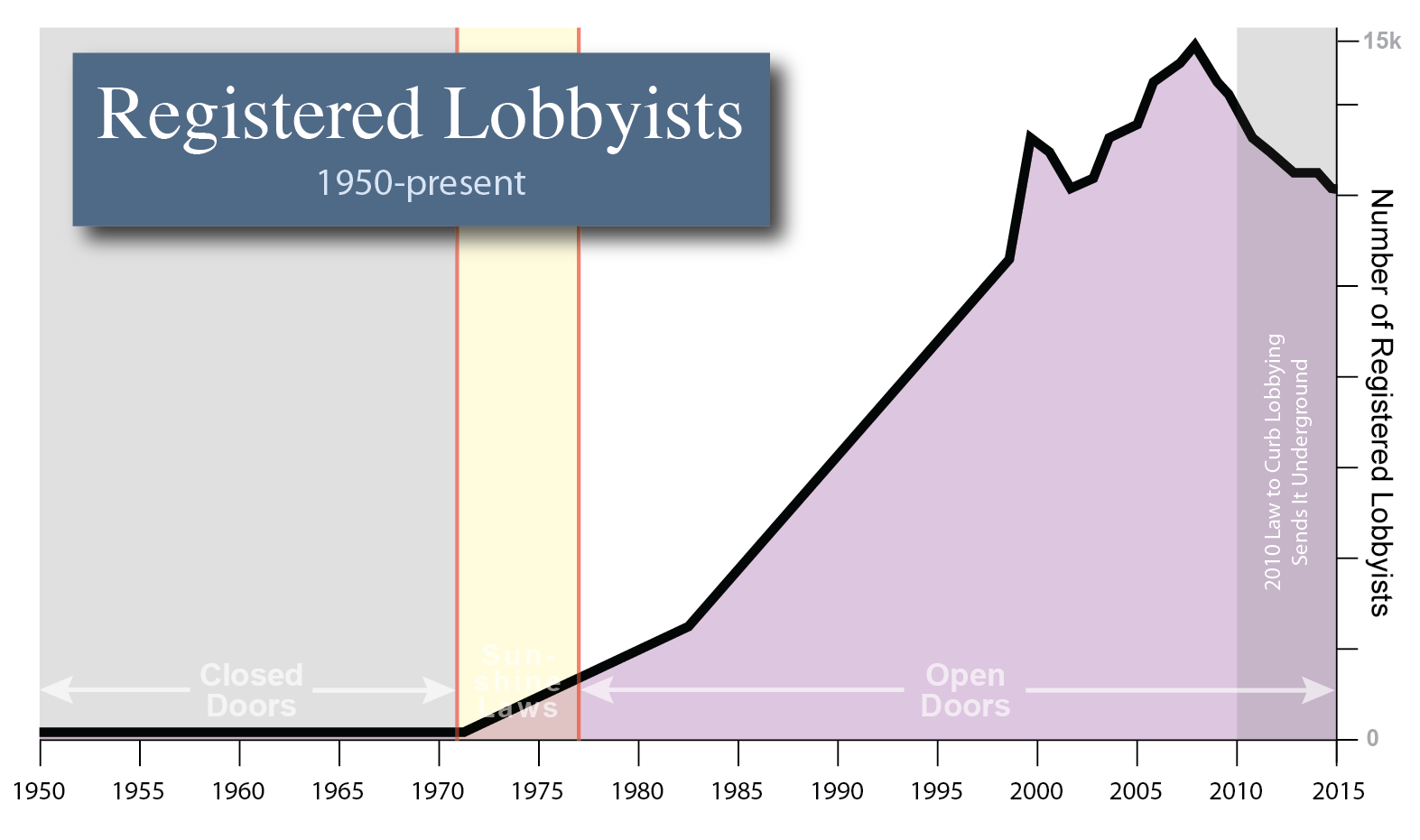

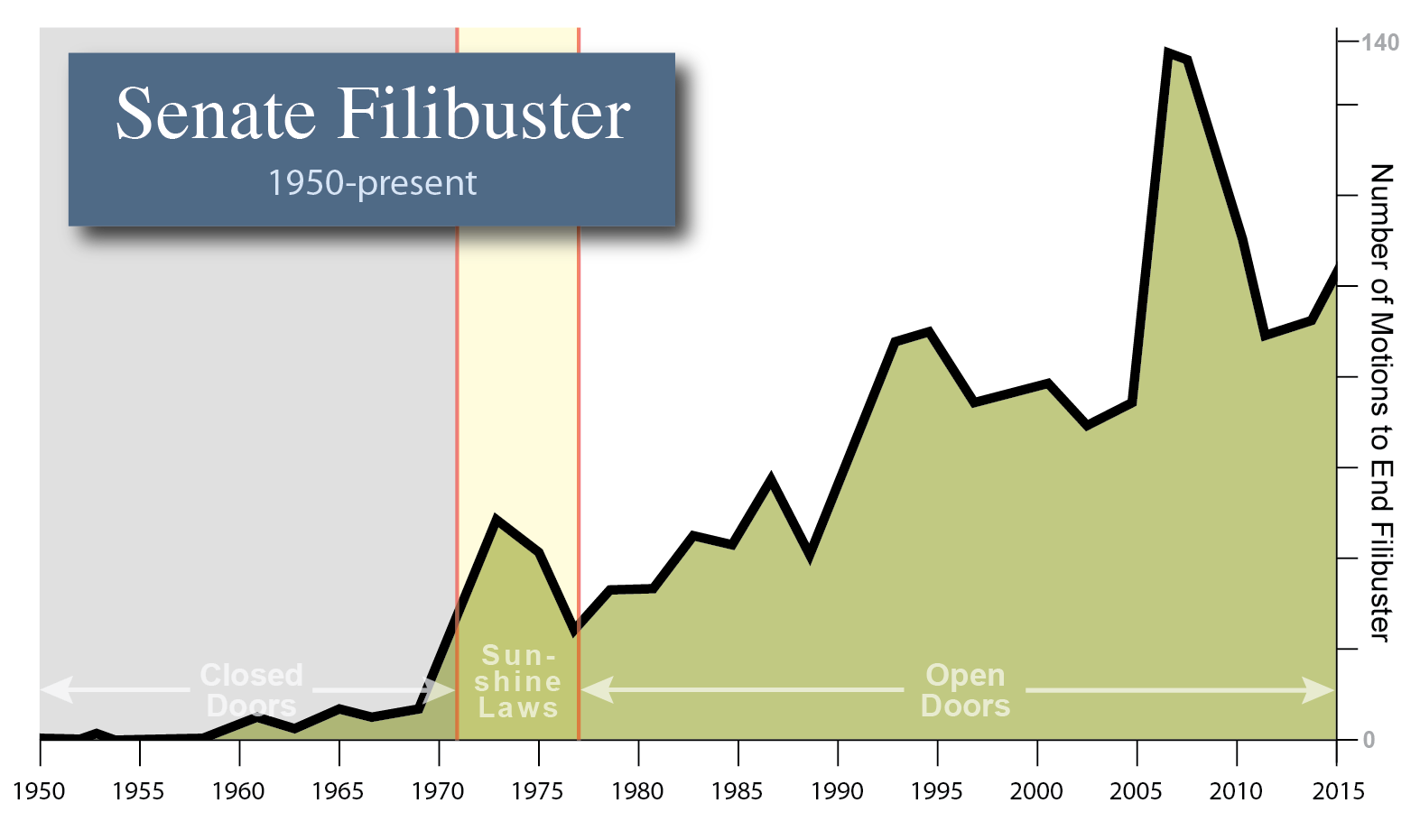

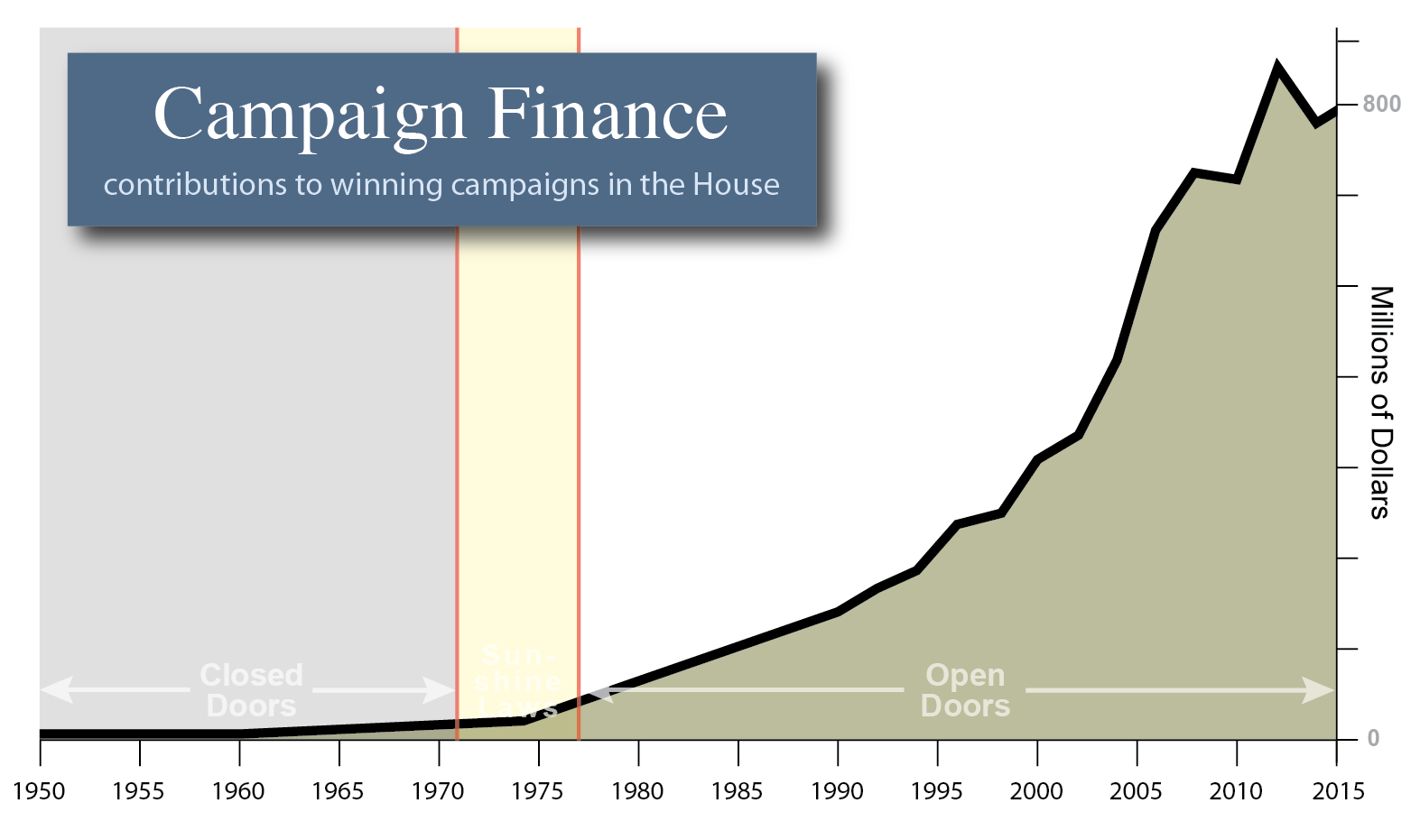

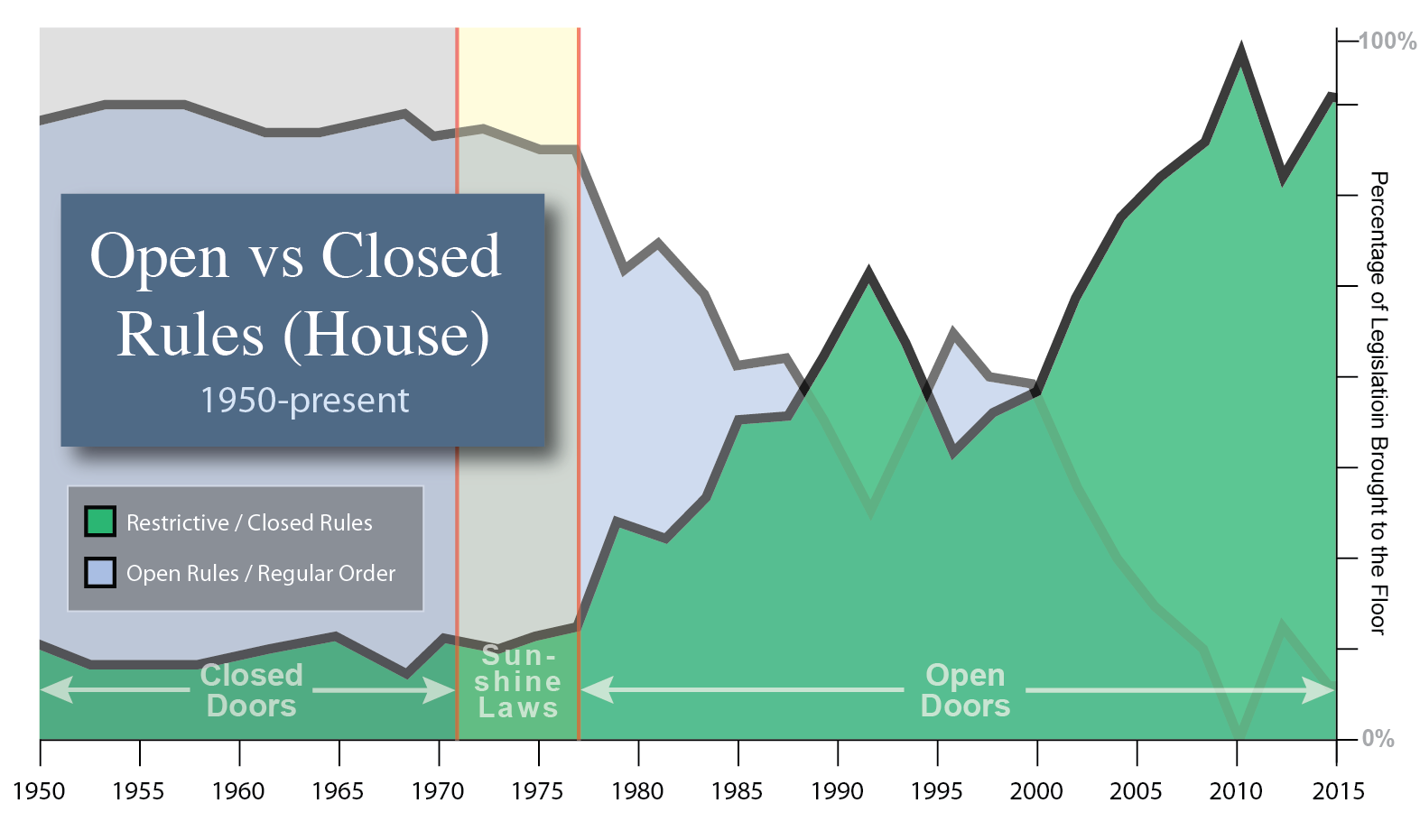

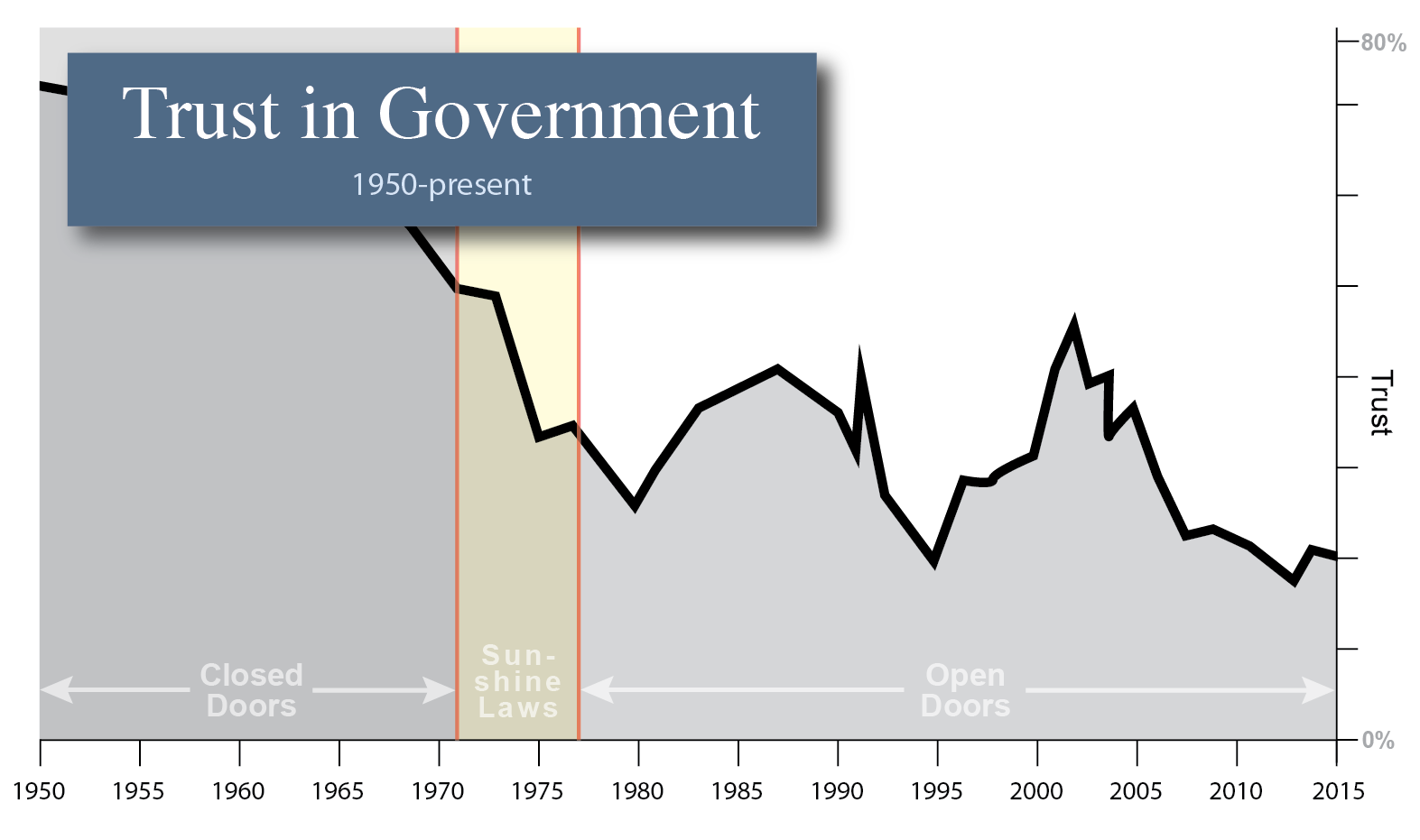

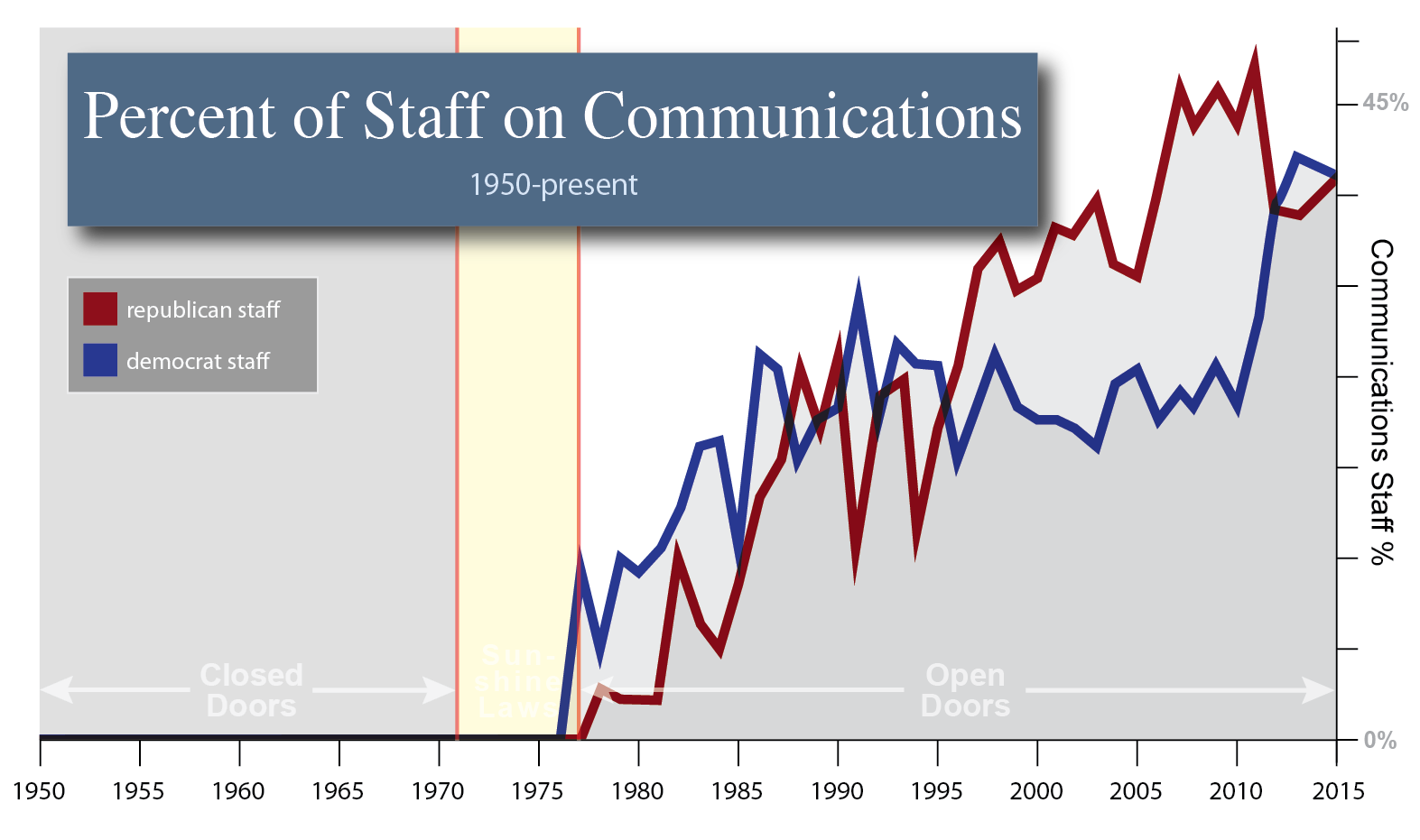

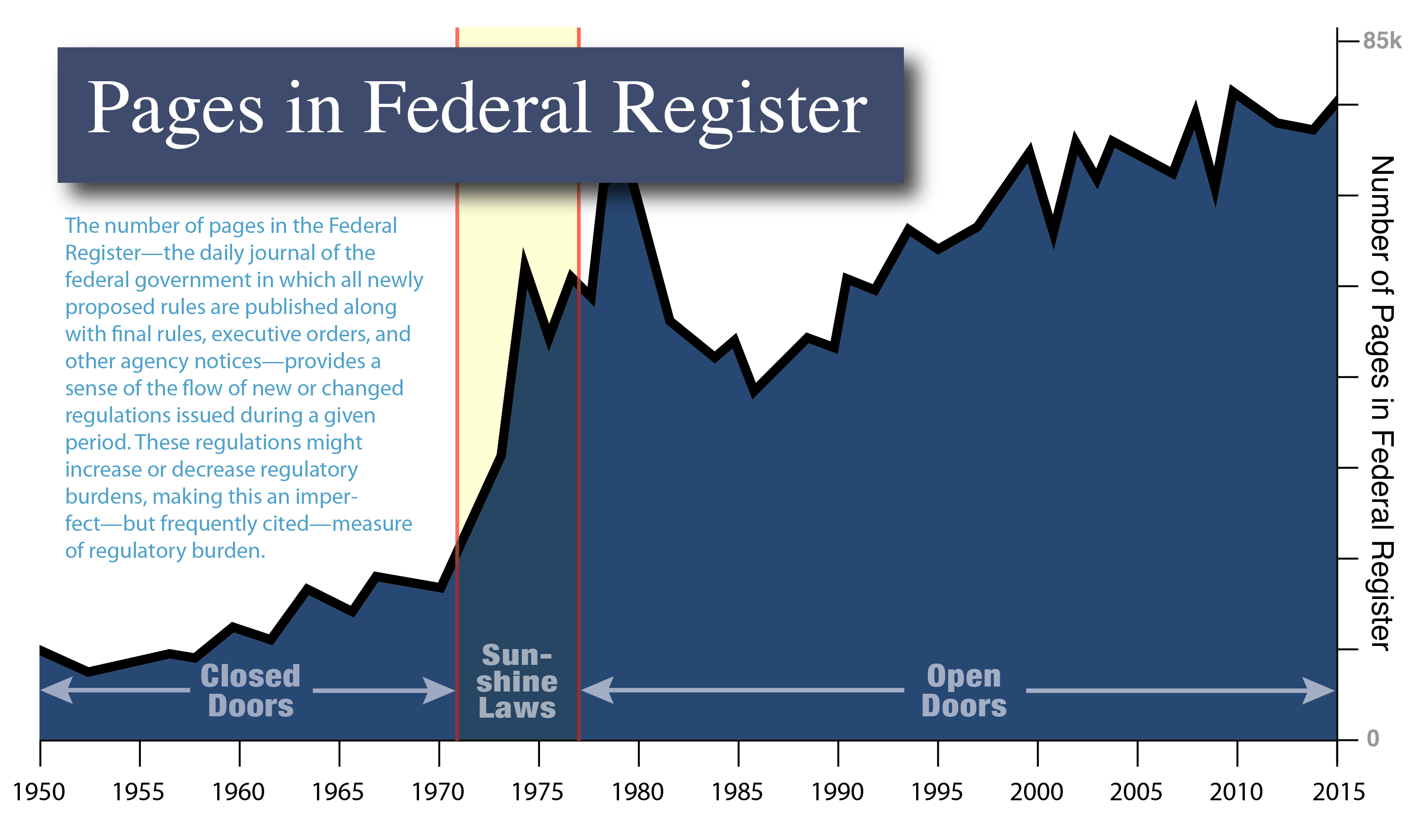

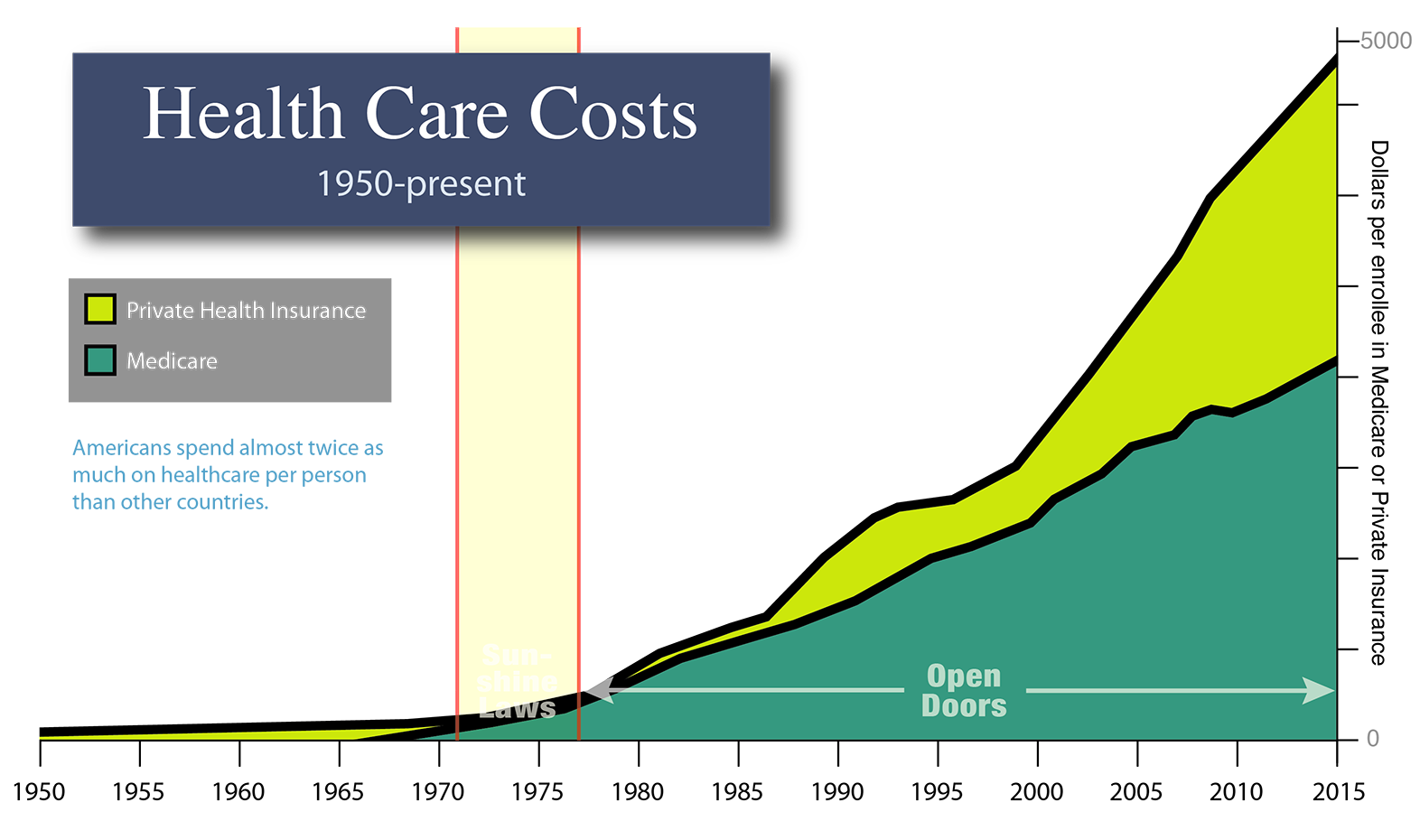

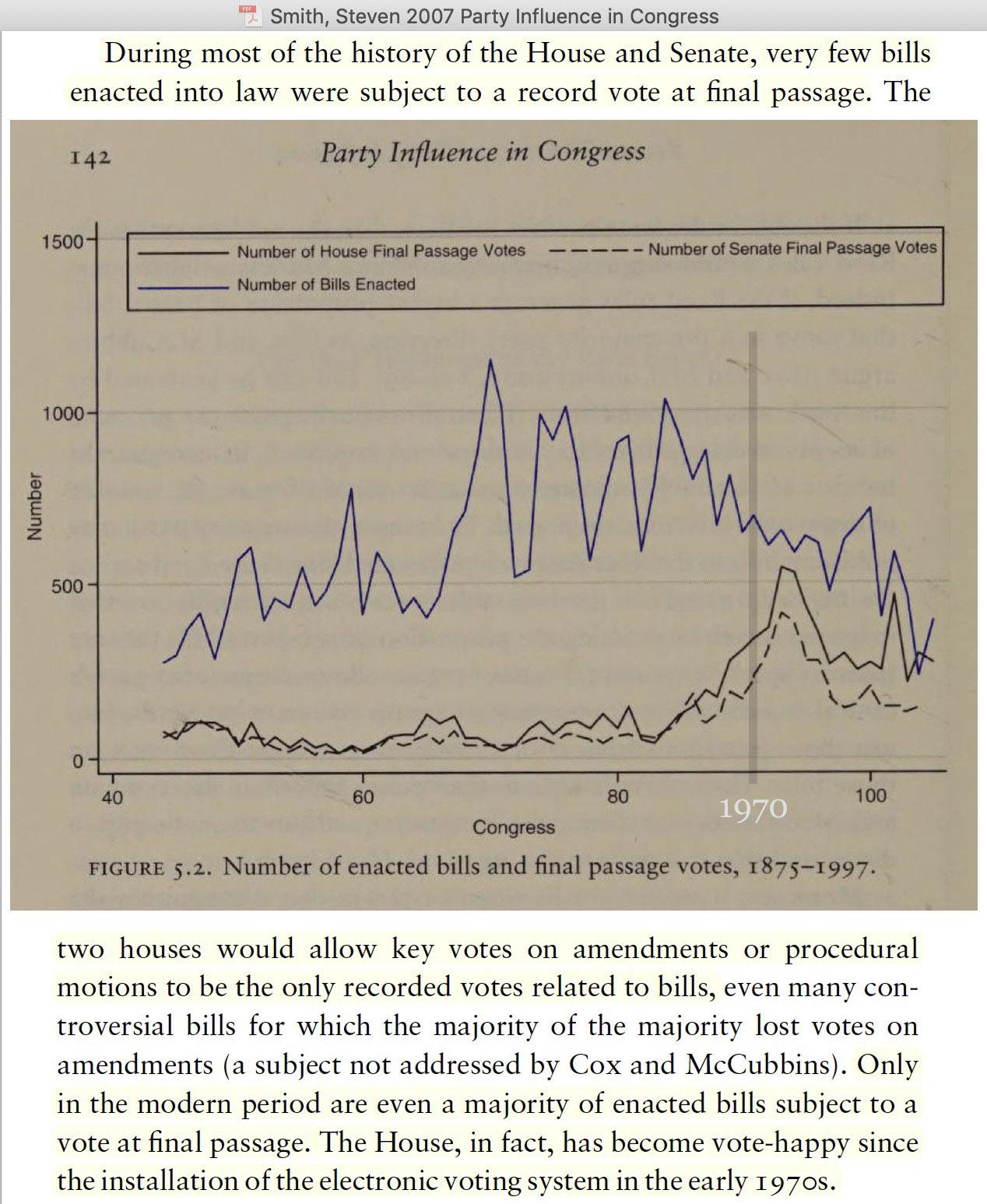

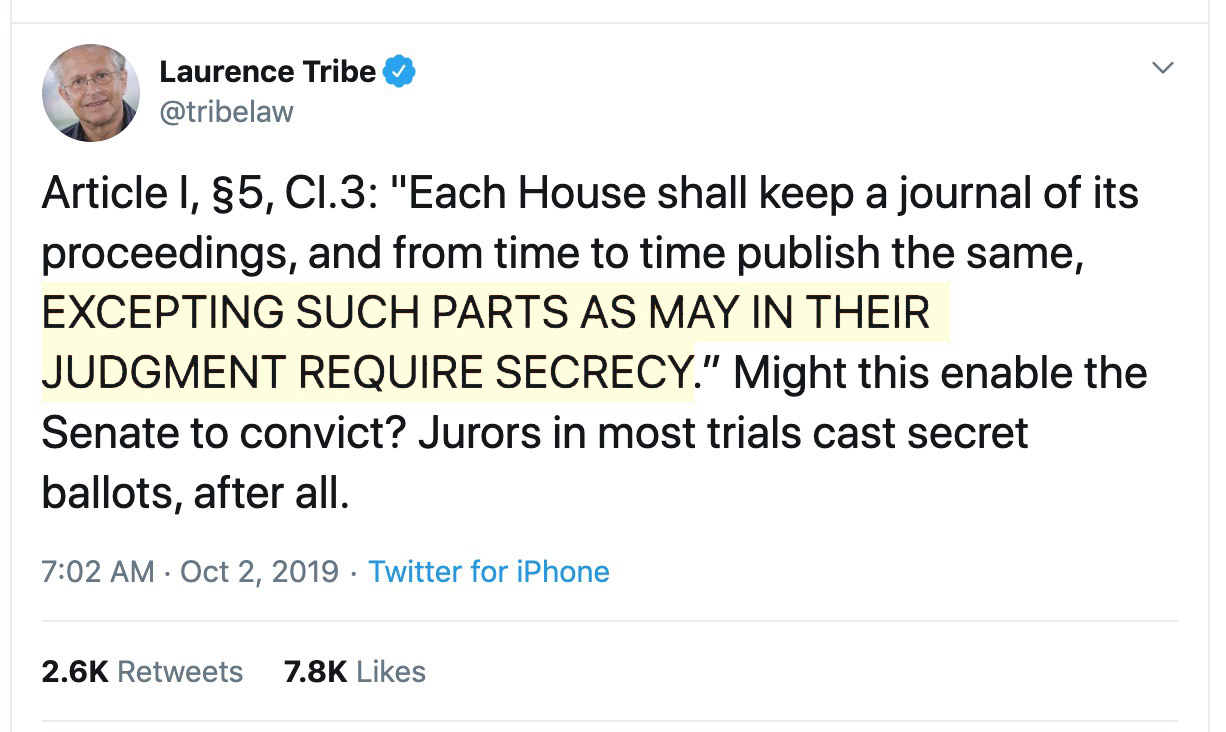

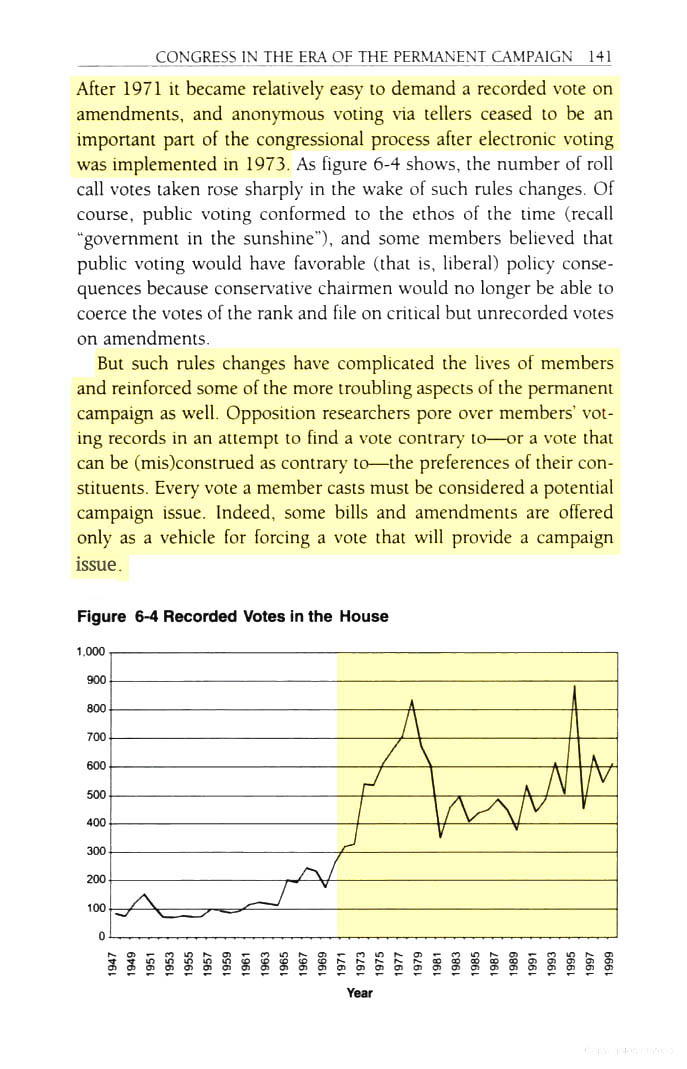

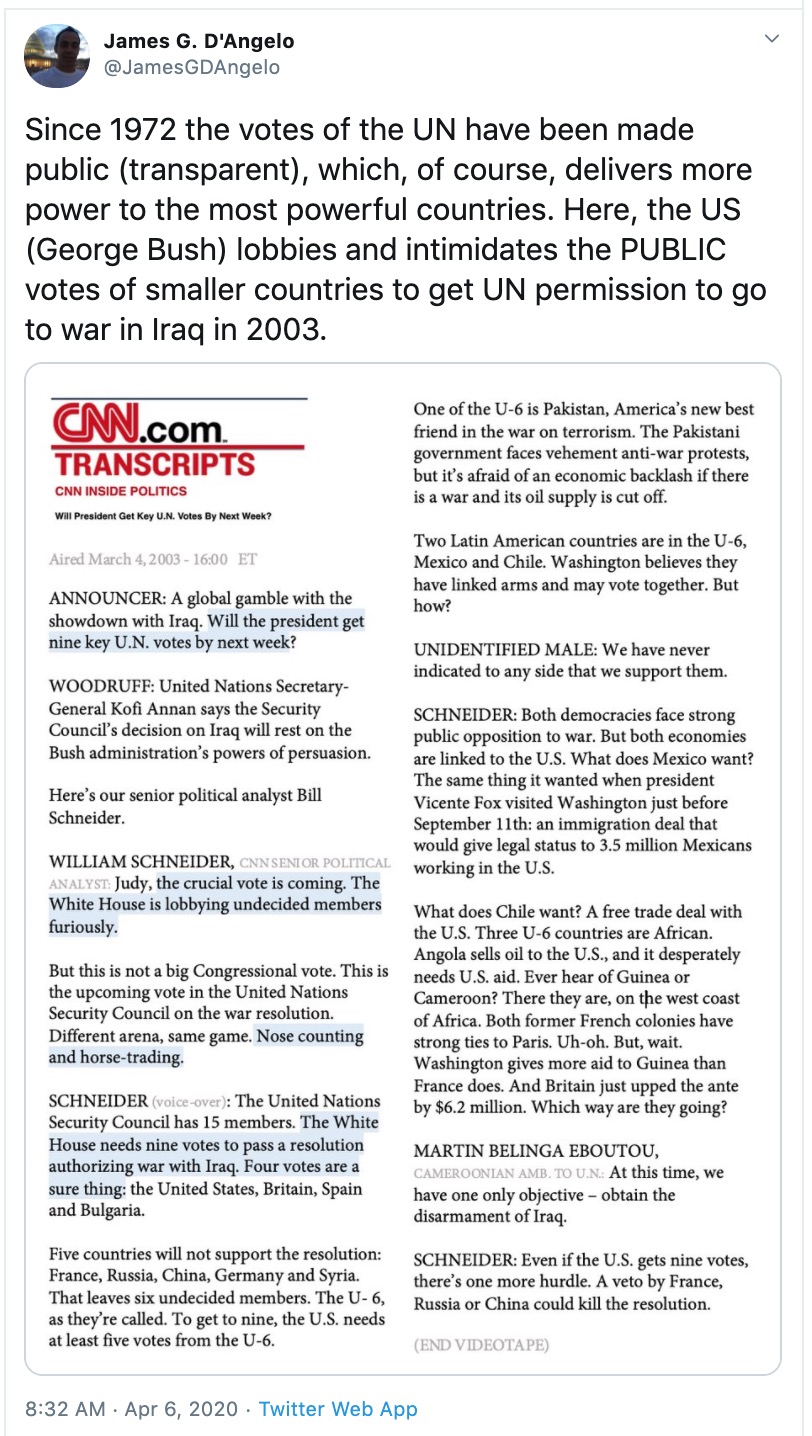

On this page we collect over a thousand academic citations on the pitfalls of legislative transparency. These include comments from some of the most celebrated political scientists, journalists, and politicos including Cicero, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison. In short, a surprising consensus appears – open door committees and public ‘roll-call’ voting leads to gridlock, partisanship, legislative warfare, soaring campaign finance and special interest capture. This is precisely what we see in the wake of the overlooked 1970 sunshine laws - laws which reject the Framers’ intentions and shun the ‘Secrecy Clause’ of the Constitution (Article I, Section 5, Clause 3).

By James D’Angelo and Brent Ranalli – March 16, 2024

Citations

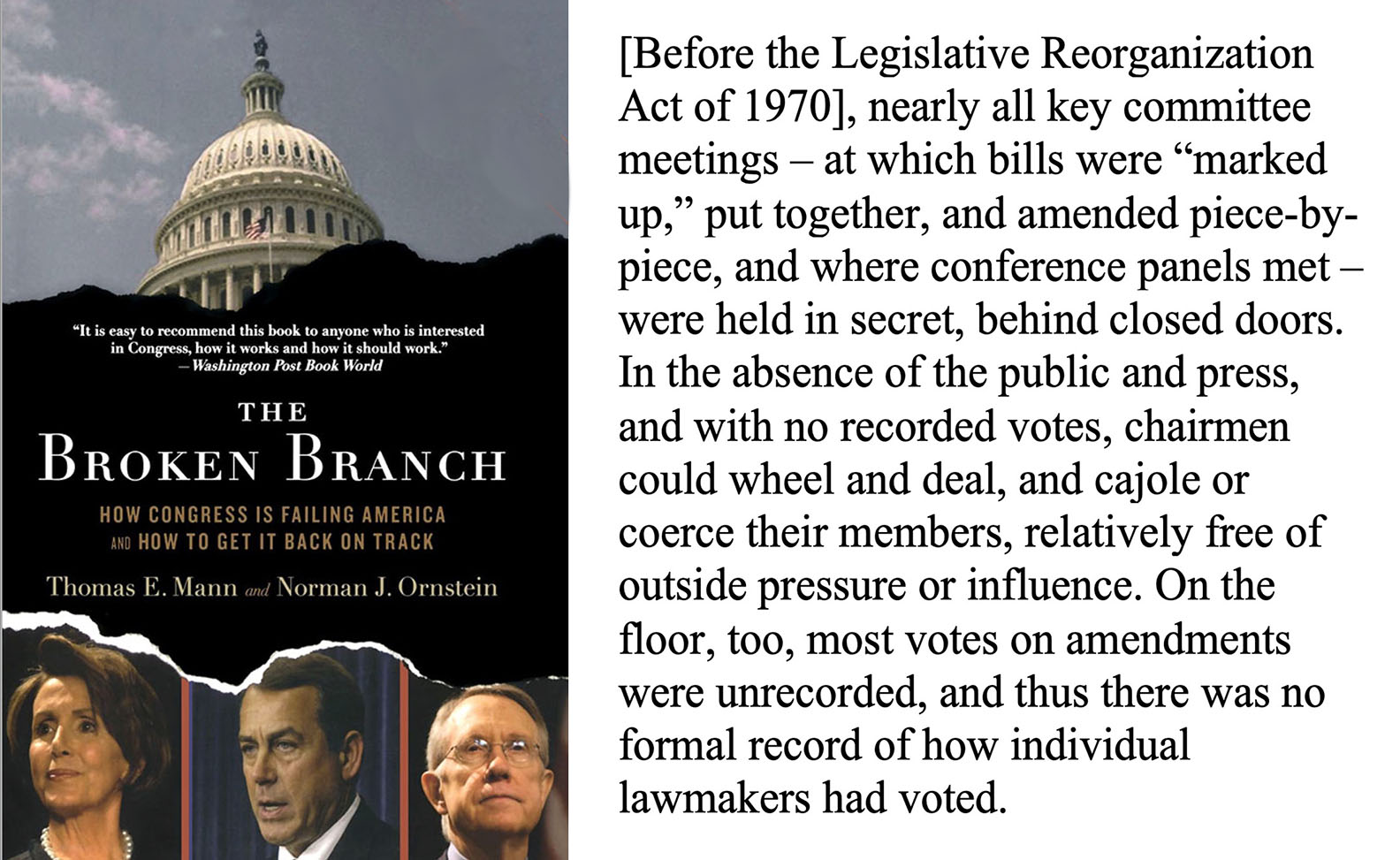

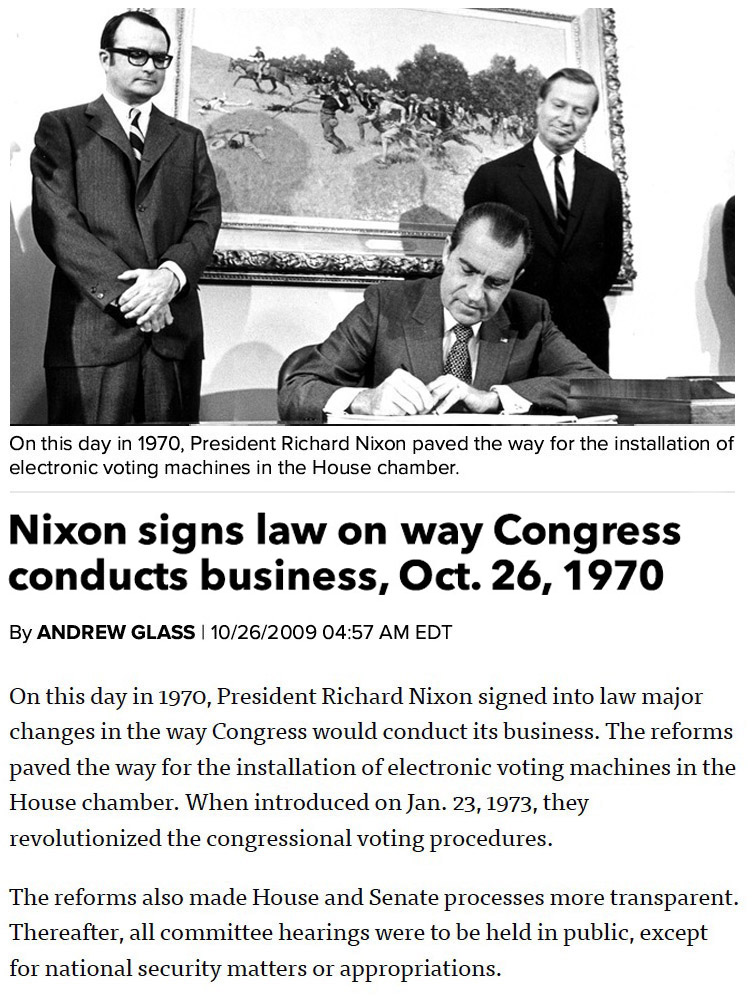

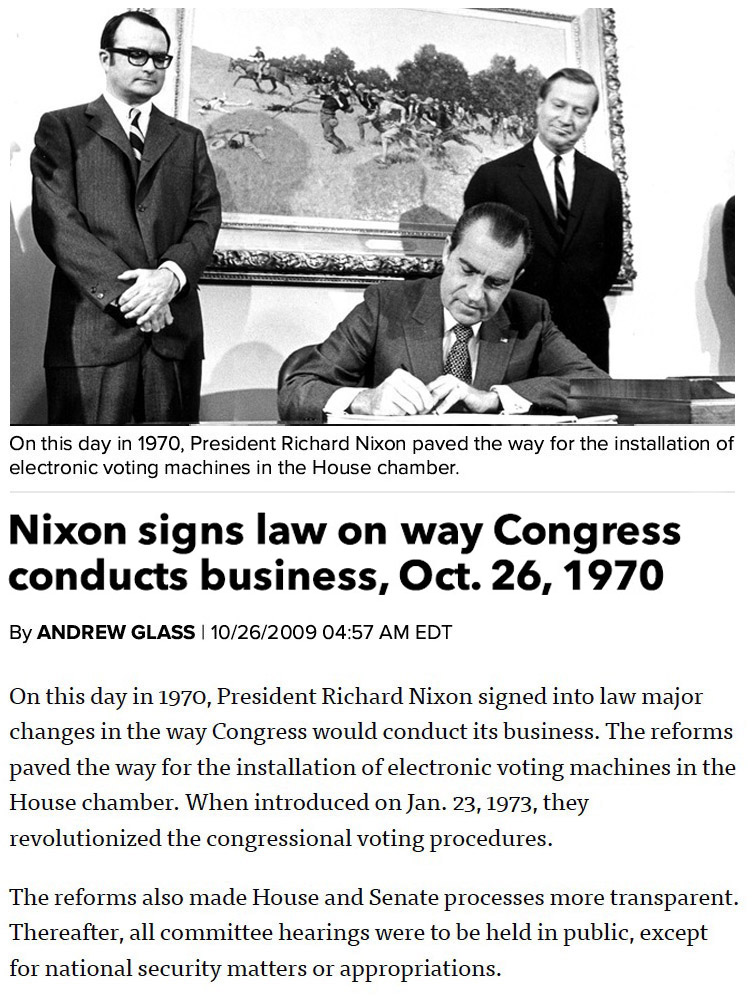

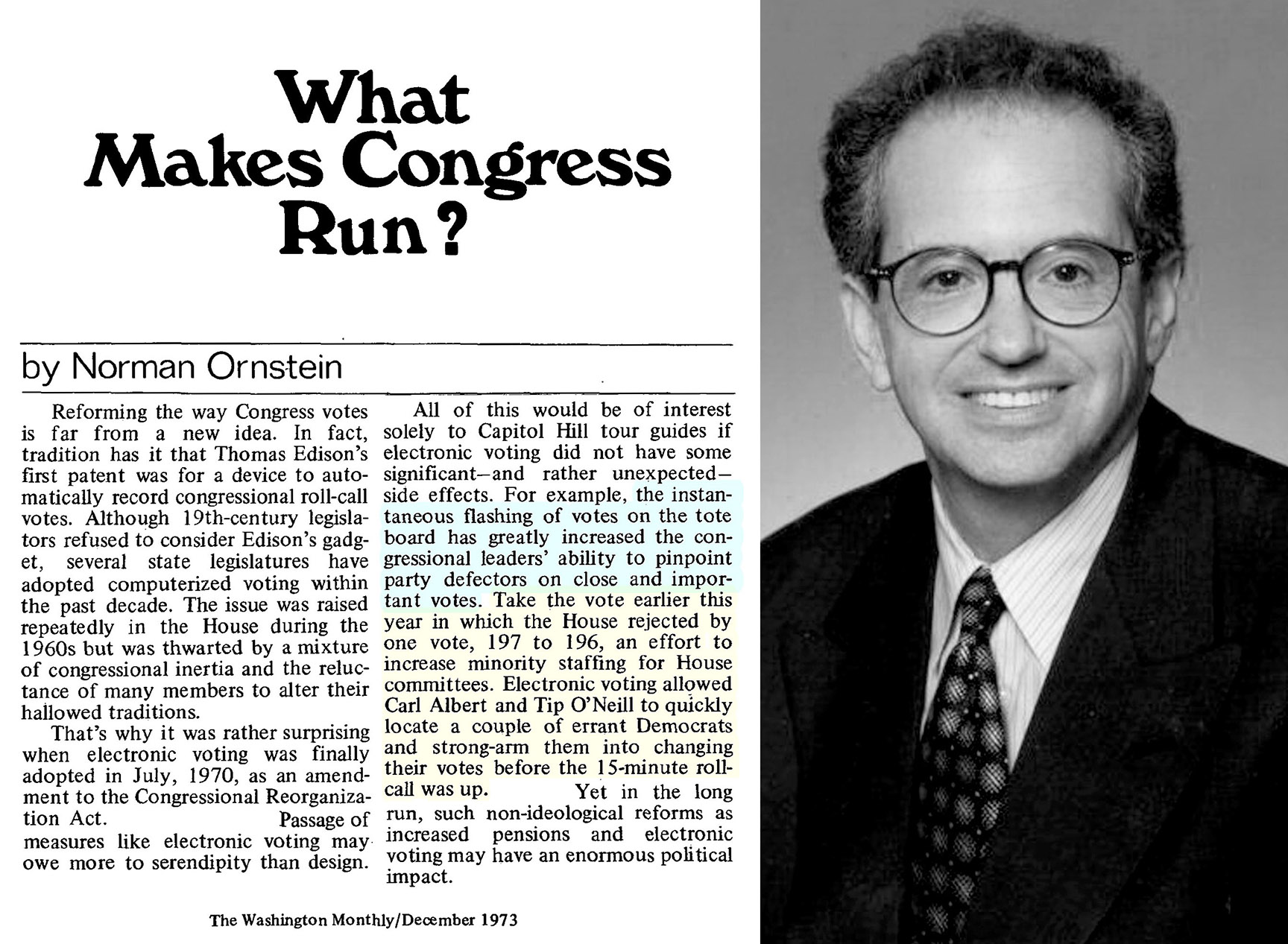

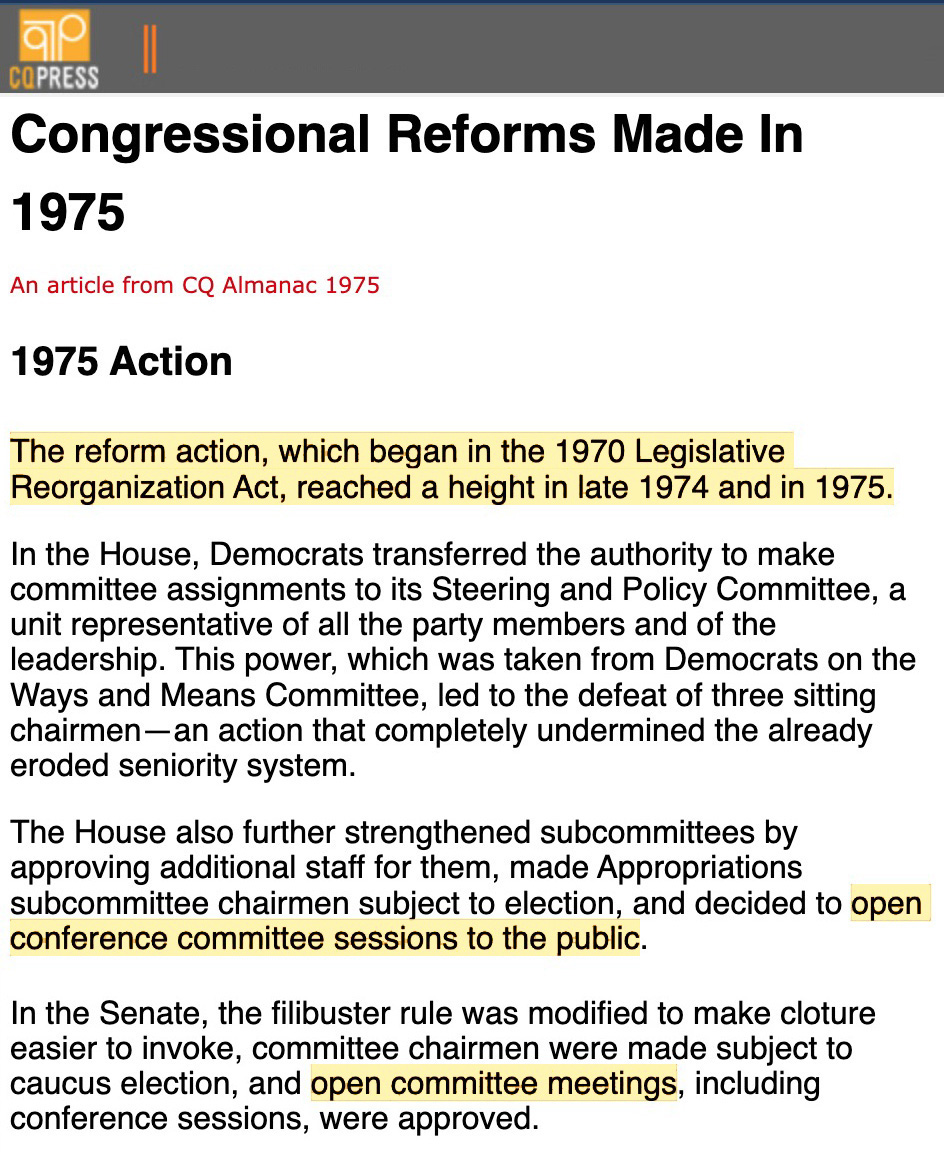

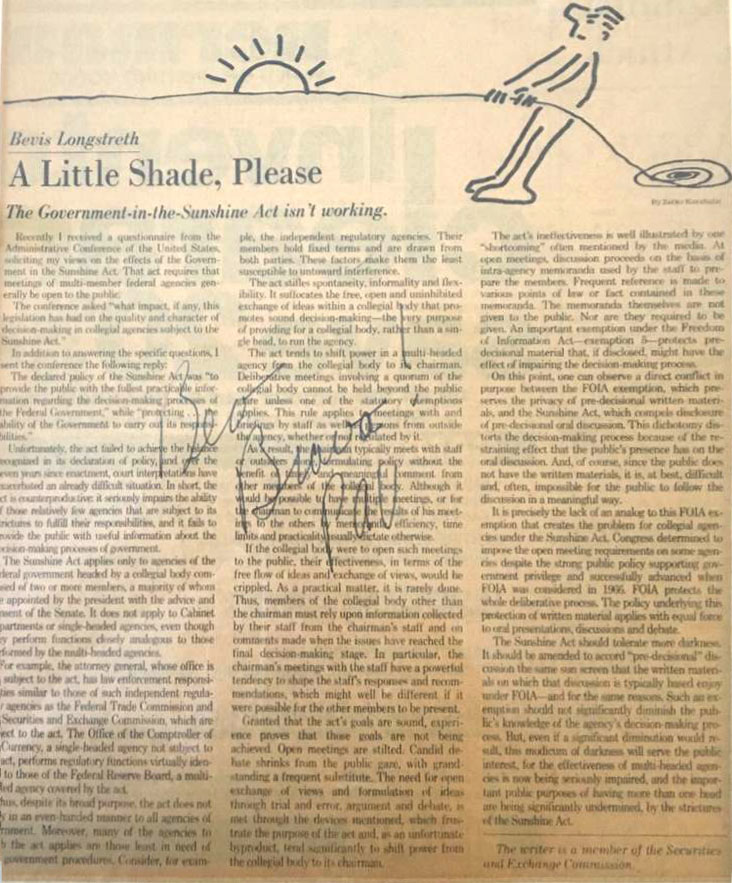

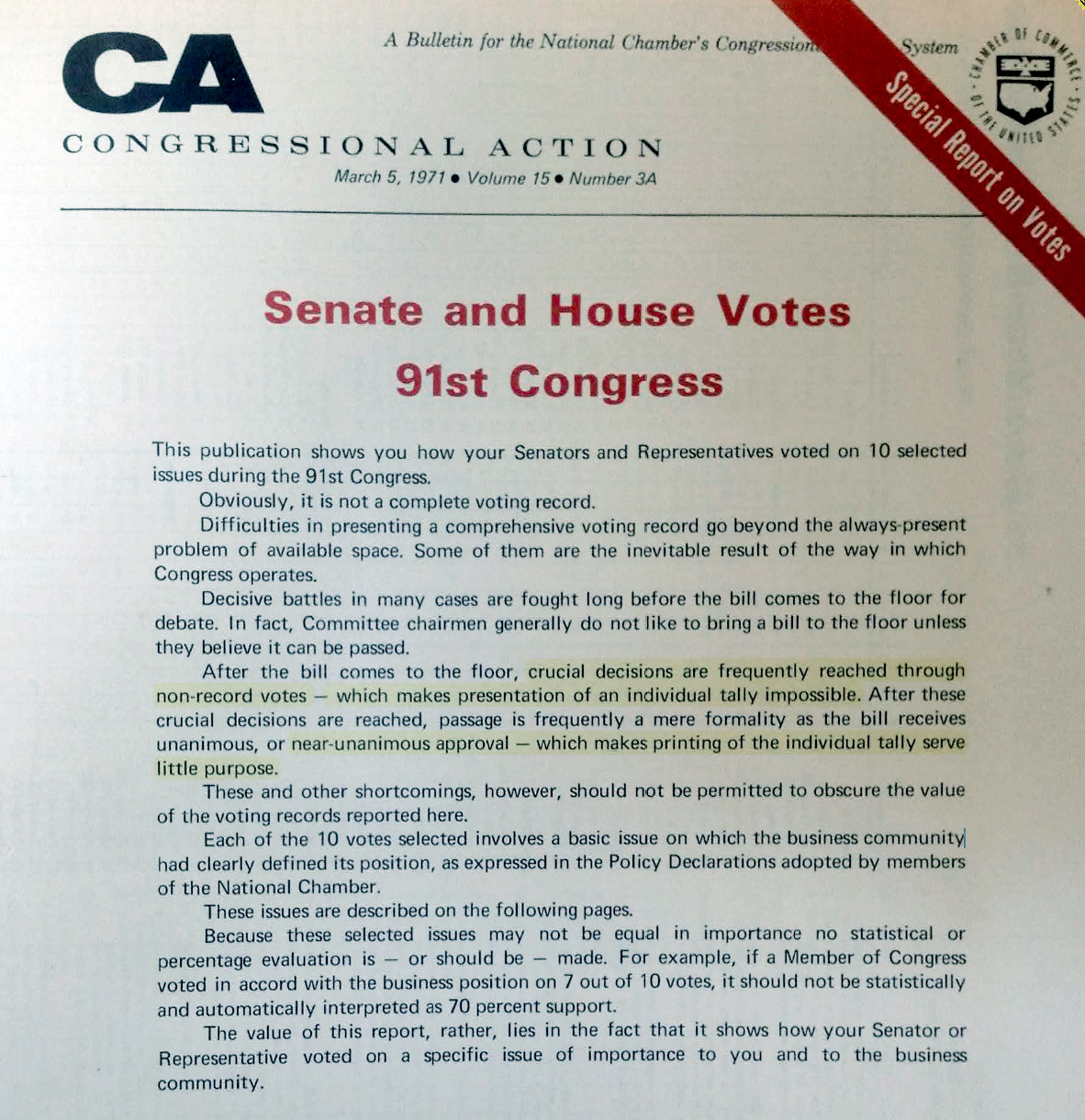

On October 26, 1970, President Nixon signed the Legislative Reorganization Act into law. The LRA countered the express intentions of the Framers who, like most congressional committees for nearly 200 years, worked behind closed doors to limit the power of factions (special interests). These citations (with links to original sources) focus on how this vast increase in congressional transparency benefits lobbyists, special interests and the powerful.

For citations on how transparency is weaponized to drive partisanship, gridlock and poor legislative outcomes, dig into the other menu items above. There we provide collections of citations on the secret ballot, perverse accountability, brubery (the opposite of bribery), and the abject lack of citizen engagement. Finally, it is worth noting that despite the amount of well funded groups pushing for greater congressional transparency, we have yet to see evidence that sunshine confers any benefit on the political process.

The more open the internal operation [of Congress], the easier it is for external groups to interpose their wishes at all stages of the process.Richard Fenno 1977

Congress Reconsidered – 1st Ed

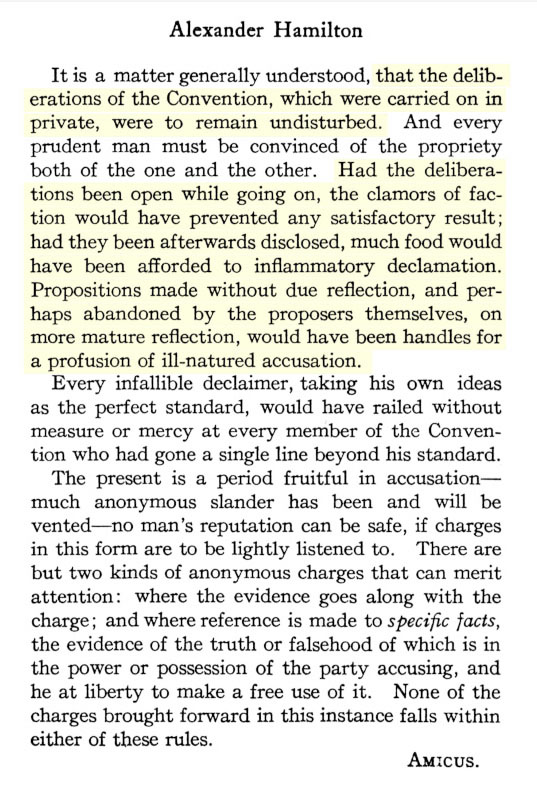

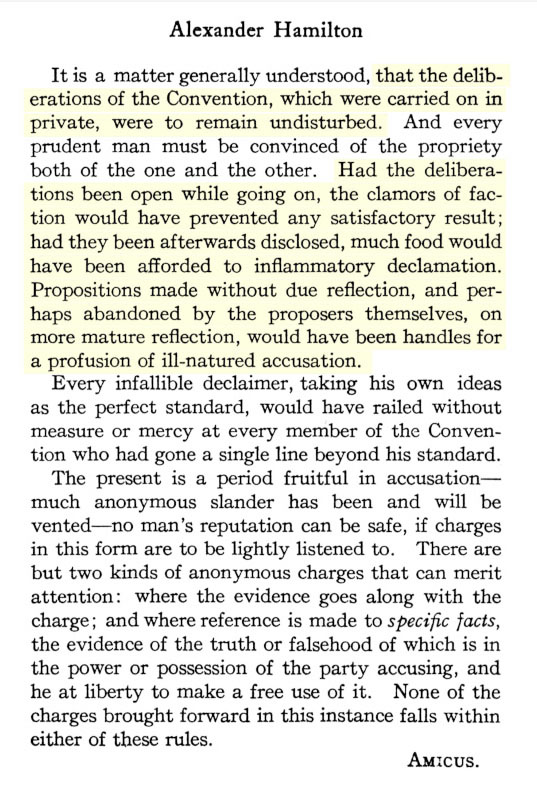

Had the deliberations been open while going on, the clamors of faction (special interests) would have prevented any satisfactory result.Alexander Hamilton 1792

History of the Republic

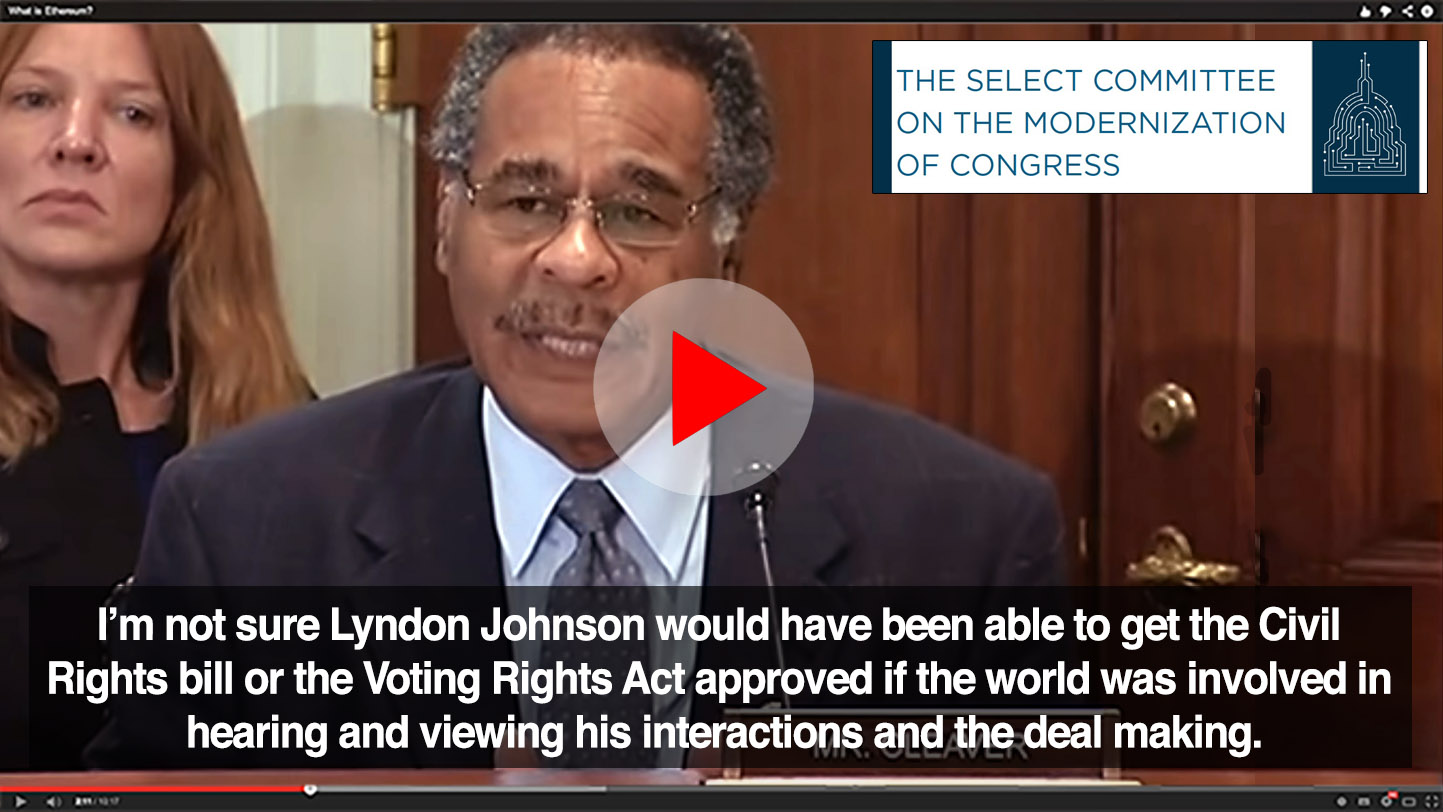

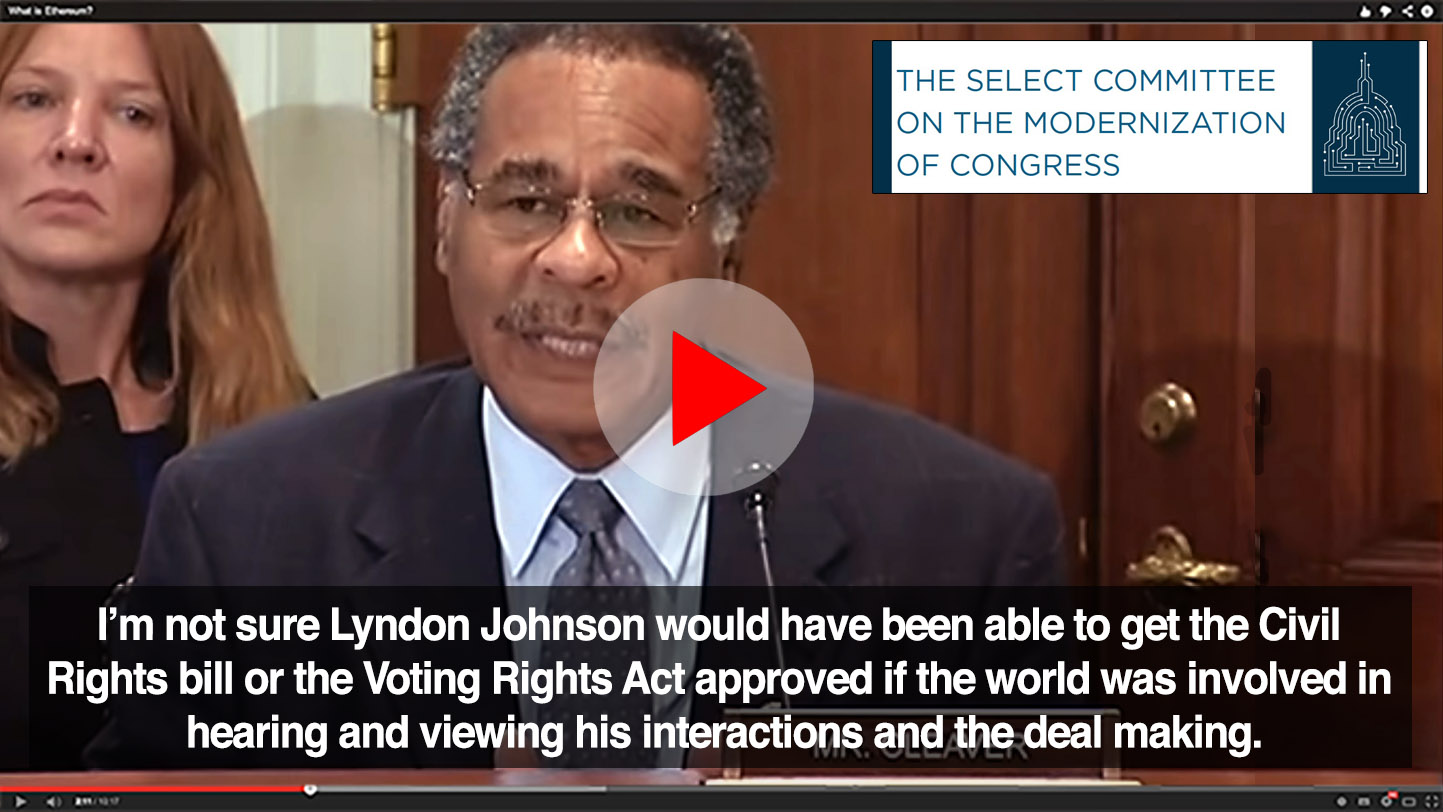

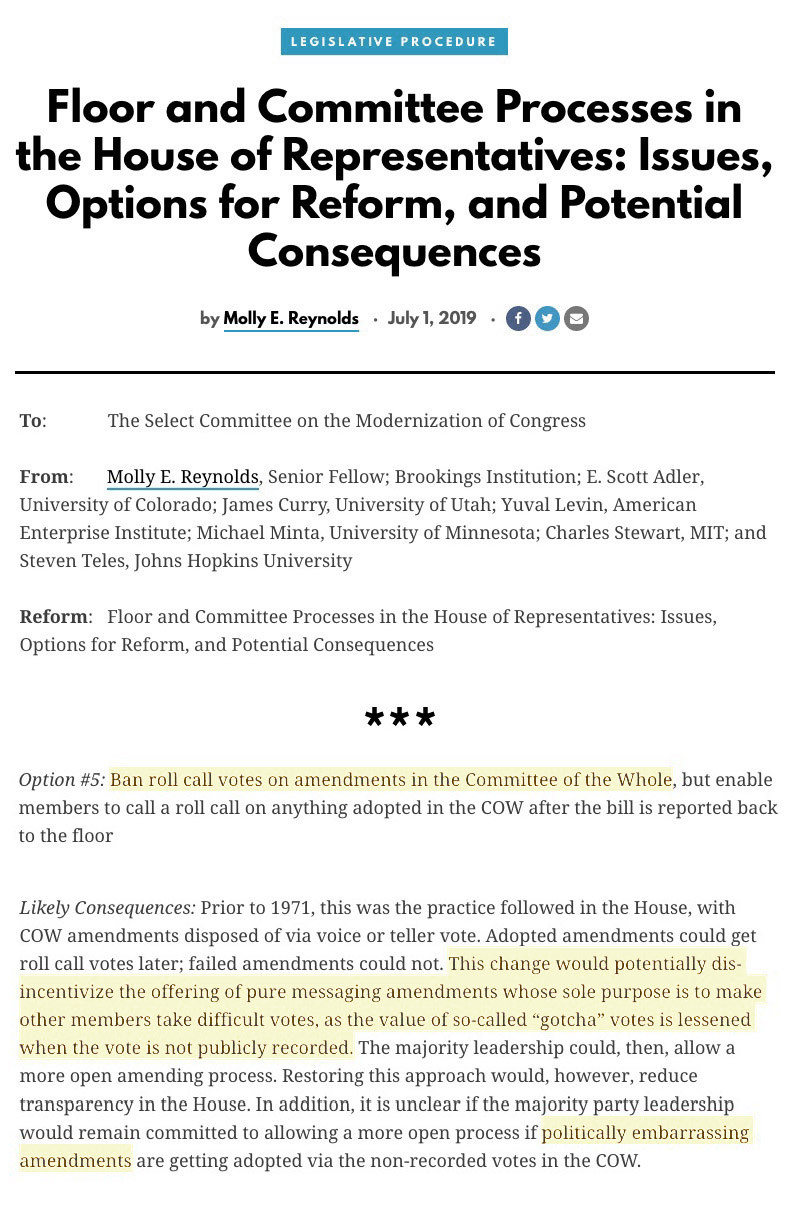

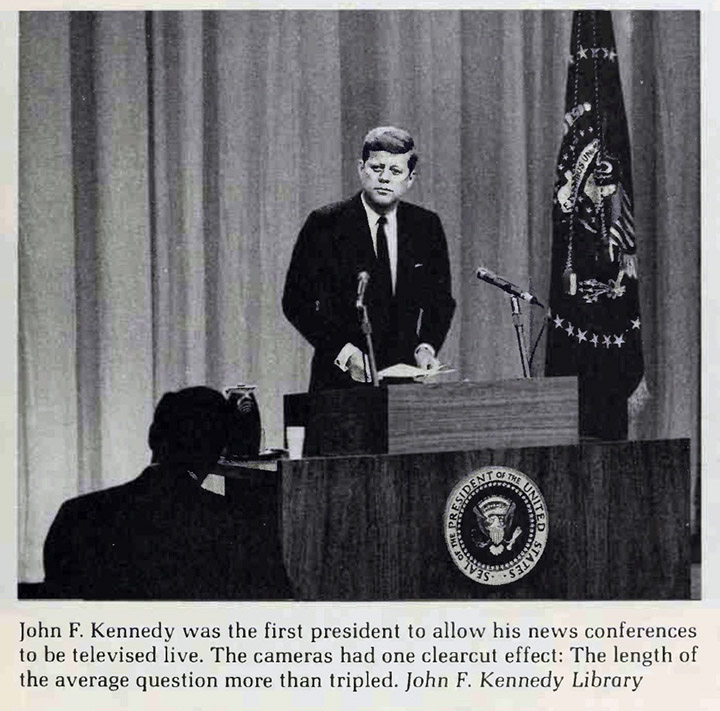

Frances Lee (Princeton) 2019 Congress: Problem with Sunshine

Frances Lee (Princeton) 2019 Congress: Problem with Sunshine

If we open up our [committees] to the public, every lobbyist in America is going to be there.Rep Harley Staggers (D-WV) 1973

Senate and House Open Up their Sessions

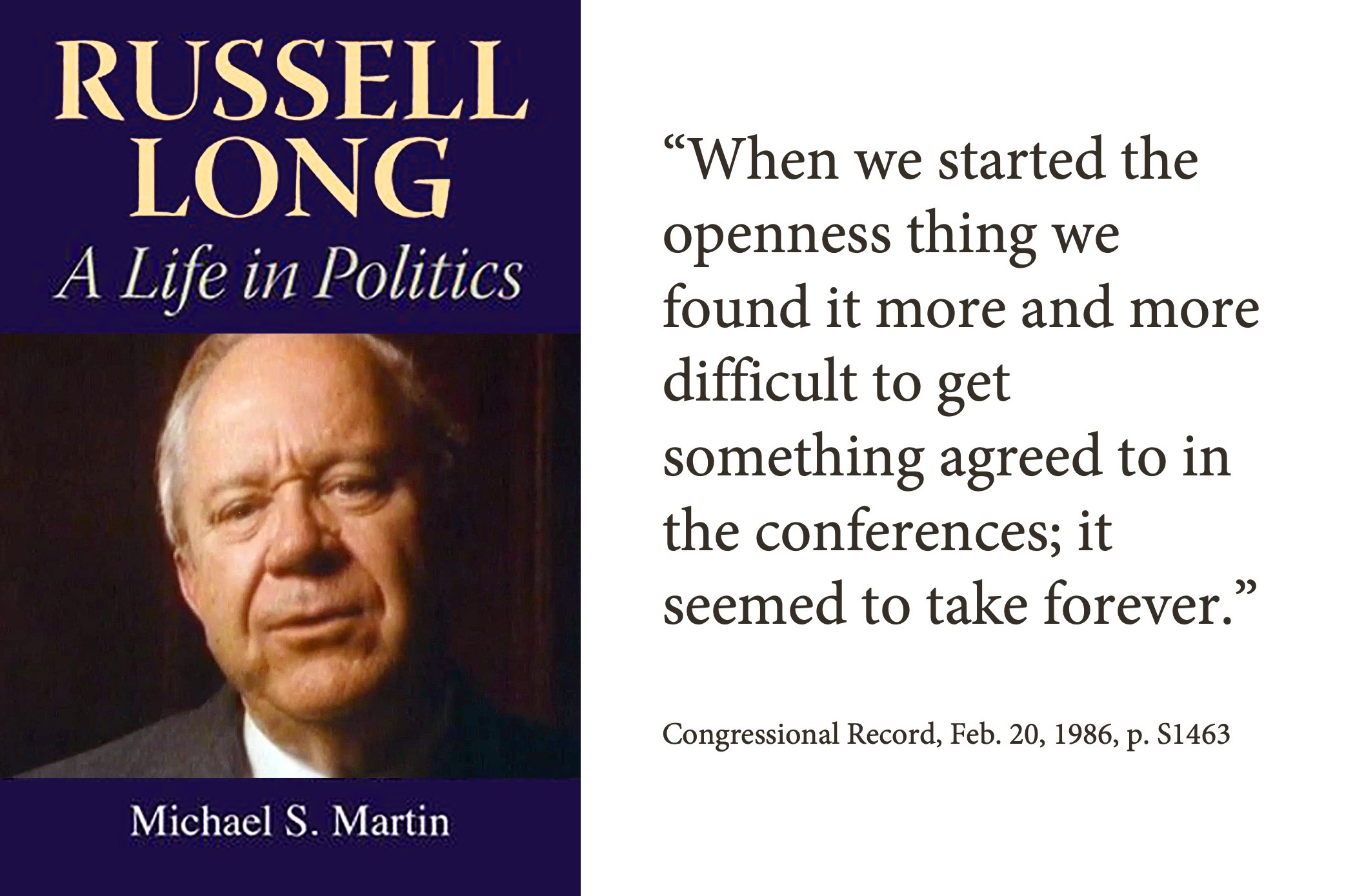

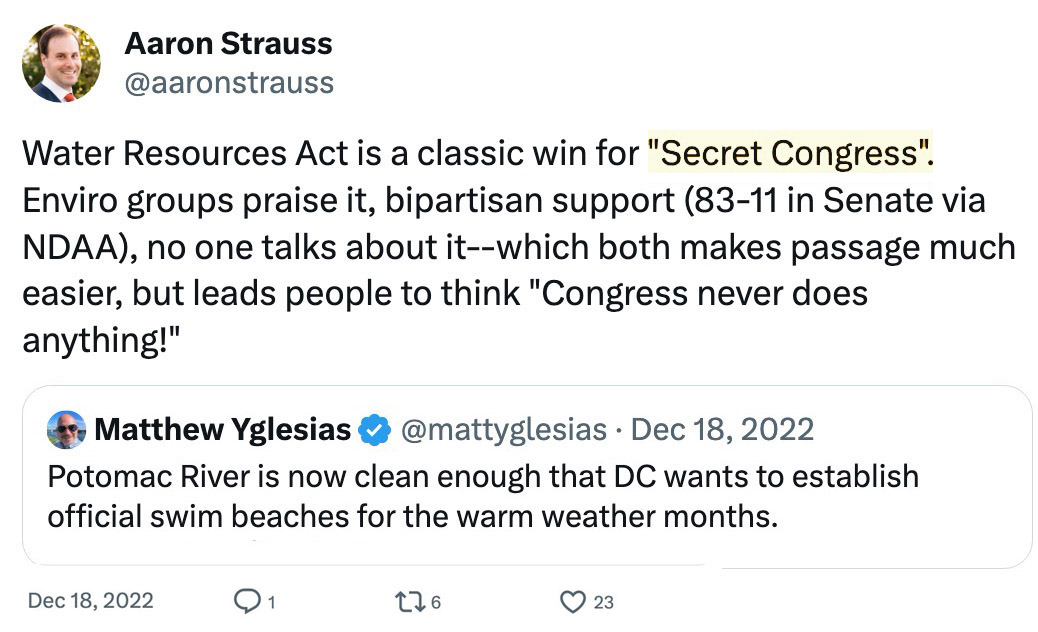

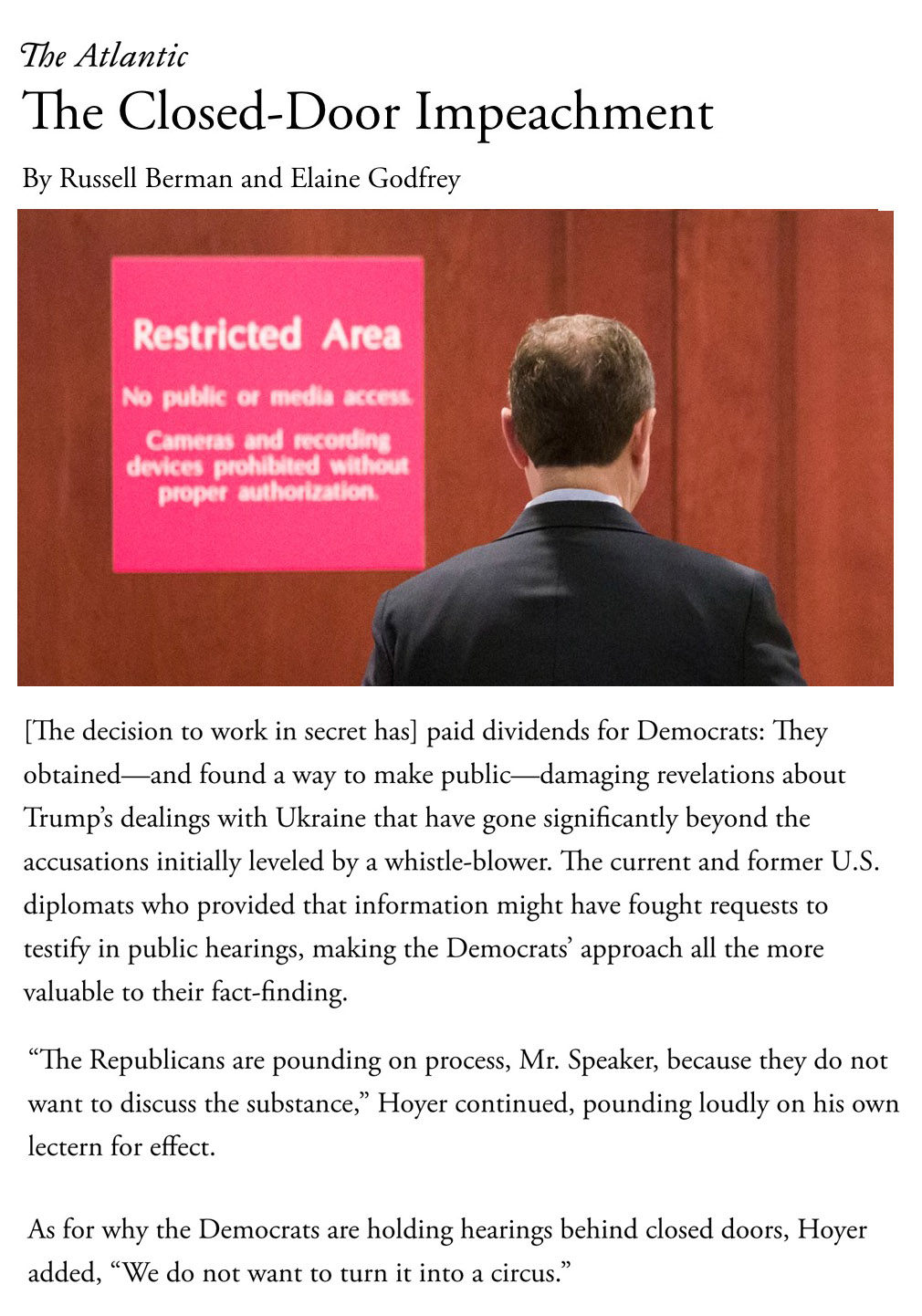

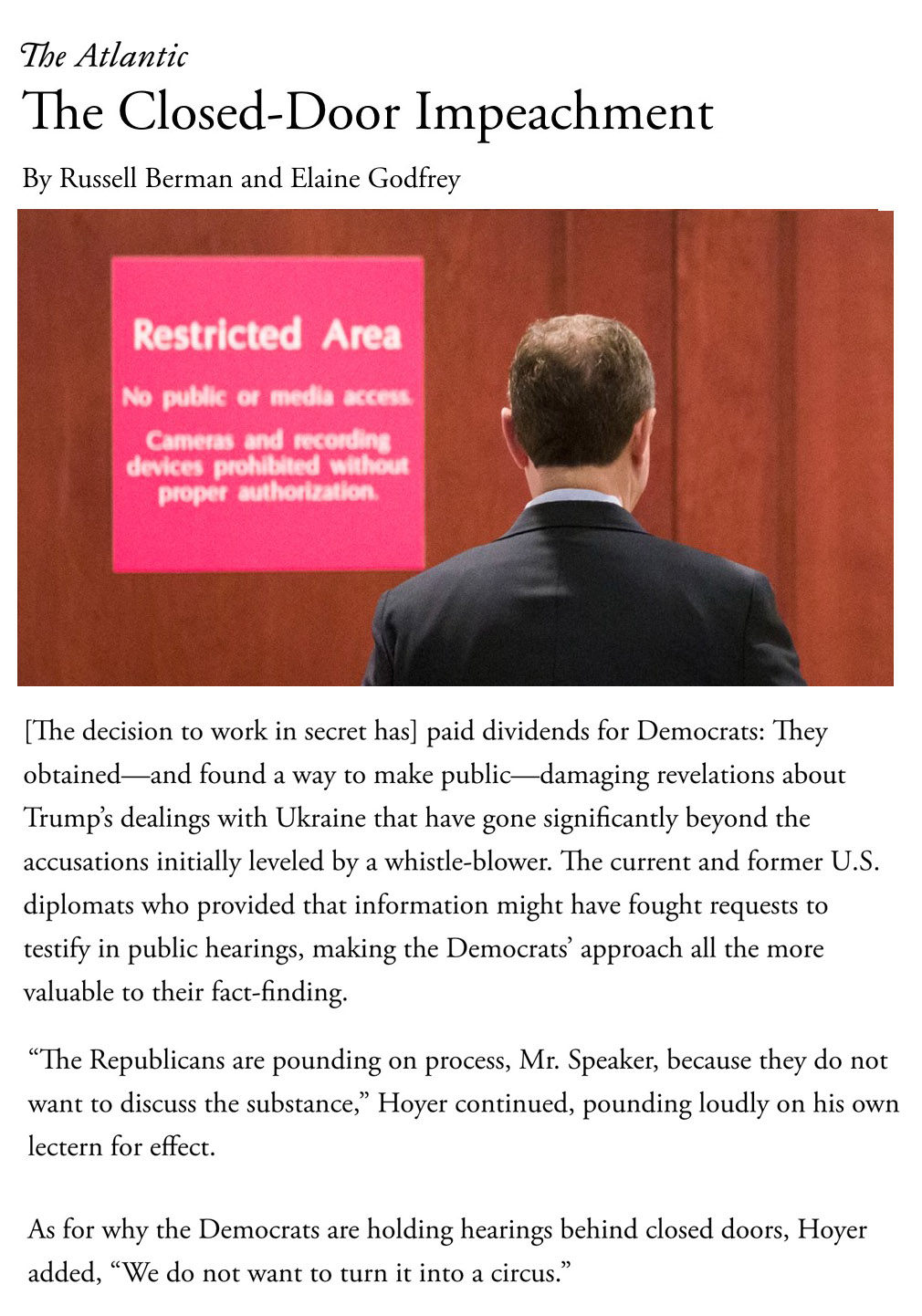

The secret to Congress’s success is secrecy.Russell Berman 2022 Atlantic Magazine

Shadow Congress

Some of the key [climate] issues debated over the past 20 years were resolved in Paris in secret meetings.Radoslav S. Dimitrov 2016

The Paris Agreement on Climate Change: Behind Closed Doors

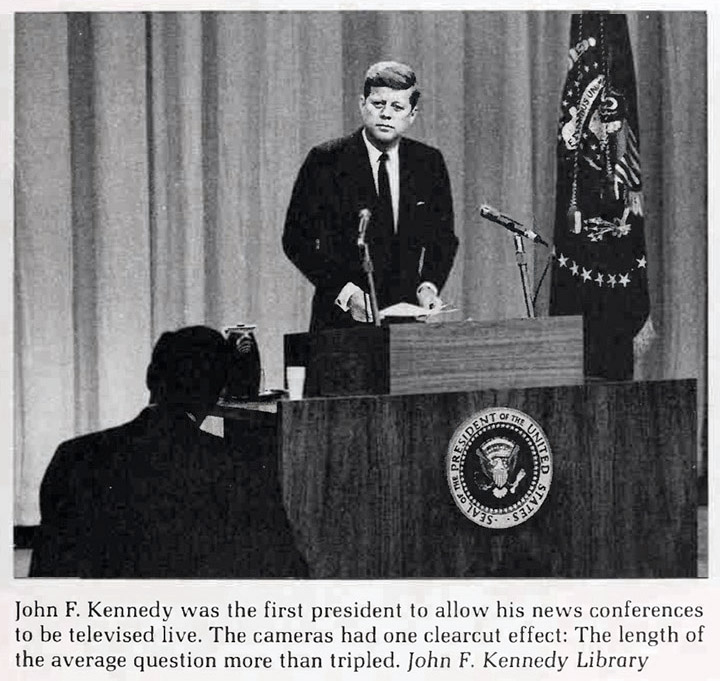

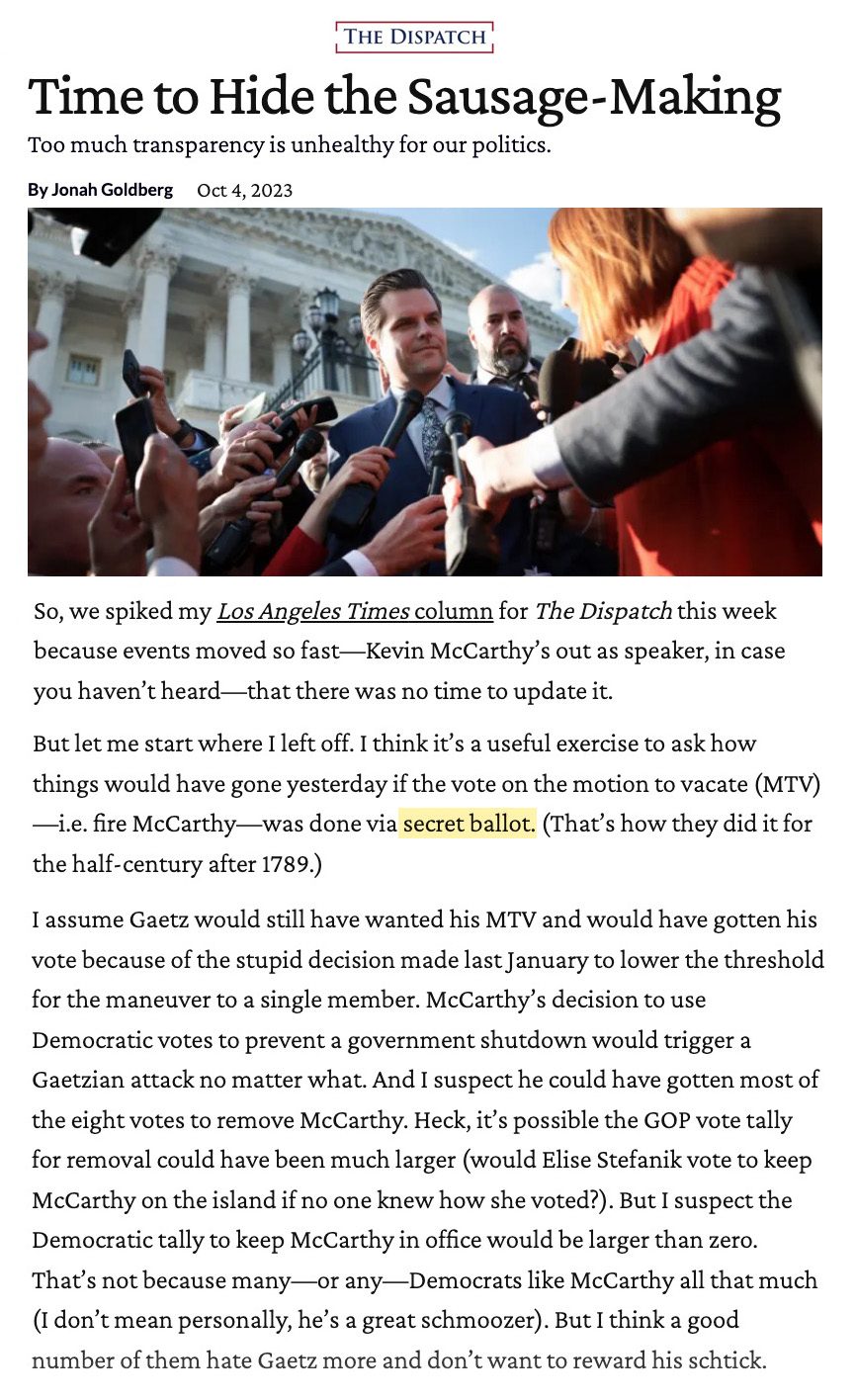

MSNBC Max Rose 2023 - Public Votes Drive Partisan Craziness

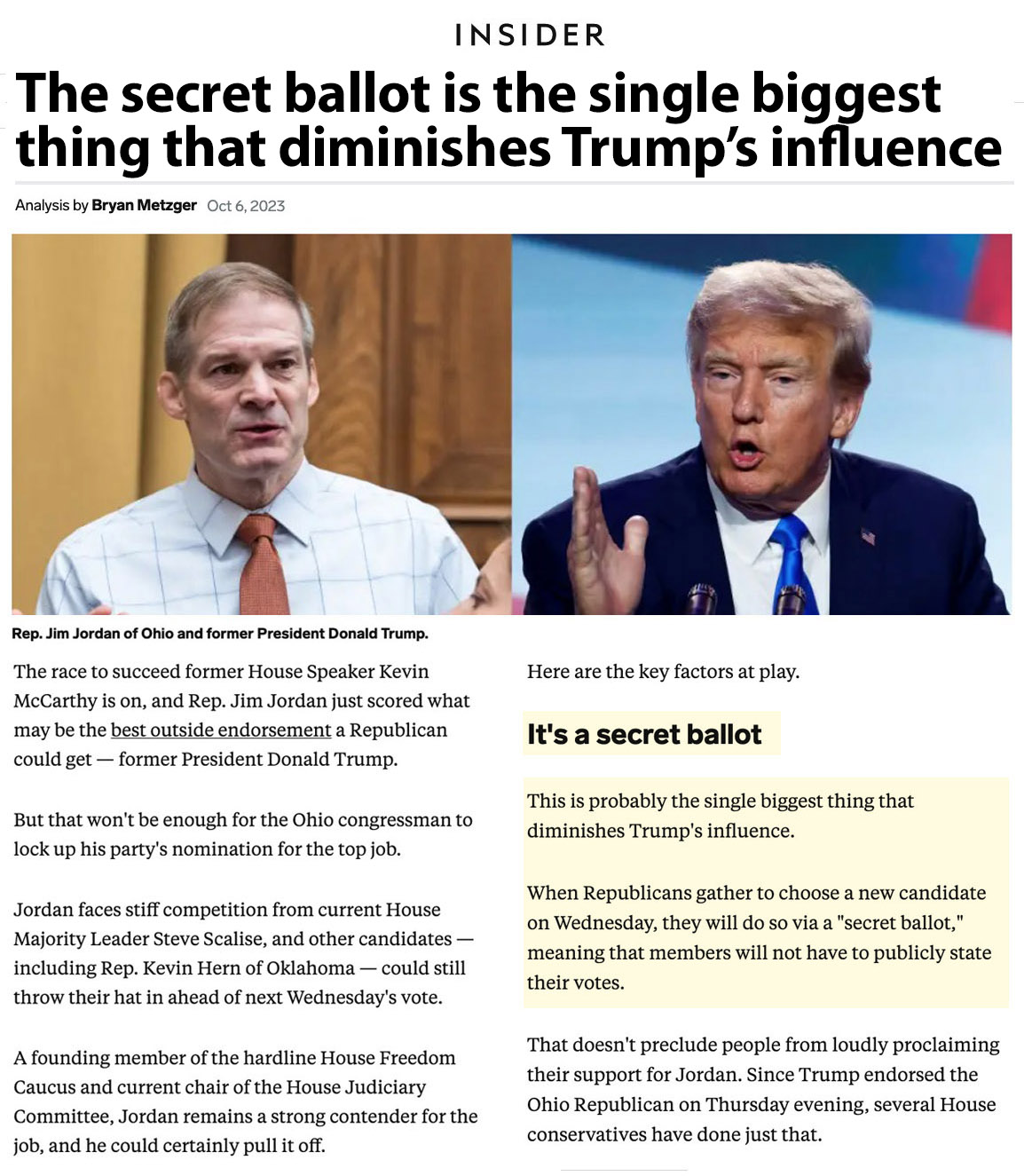

Text from October 11, 2023 on the Morning Joe Show with guest former Representative Max Rose - in a conversation about the secret ballot voting for the House speaker: "The thing with this vote behind closed doors, that's not gonna be the hurdle. Any time you get behind closed doors the extremists become somehow subdued. You know, they are not allowed their cameras, their phones, and not just because that leaks, but so they can't take a photo of their ballots. And so when they can't take a phot of their ballot, they don't have anything to show, whether its a text to Donald Trump, or to his people, or to his extremist base. But the danger will come when they have to go out in public and take that public vote."

MSNBC Max Rose 2023 - Public Votes Drive Partisan Craziness

Sunshine reforms have proved more useful to lobbyists than to average Americans.Frances Lee (Princeton) 2019

Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress

The more open a system becomes, the more easily it can be penetrated by money, lobbyists and fanatics… Congress can now be monitored and influenced as never before. As a result, lobbies, which do most of the monitoring and influencing, have gained power.Fareed Zakaria 2003

Future of Freedom

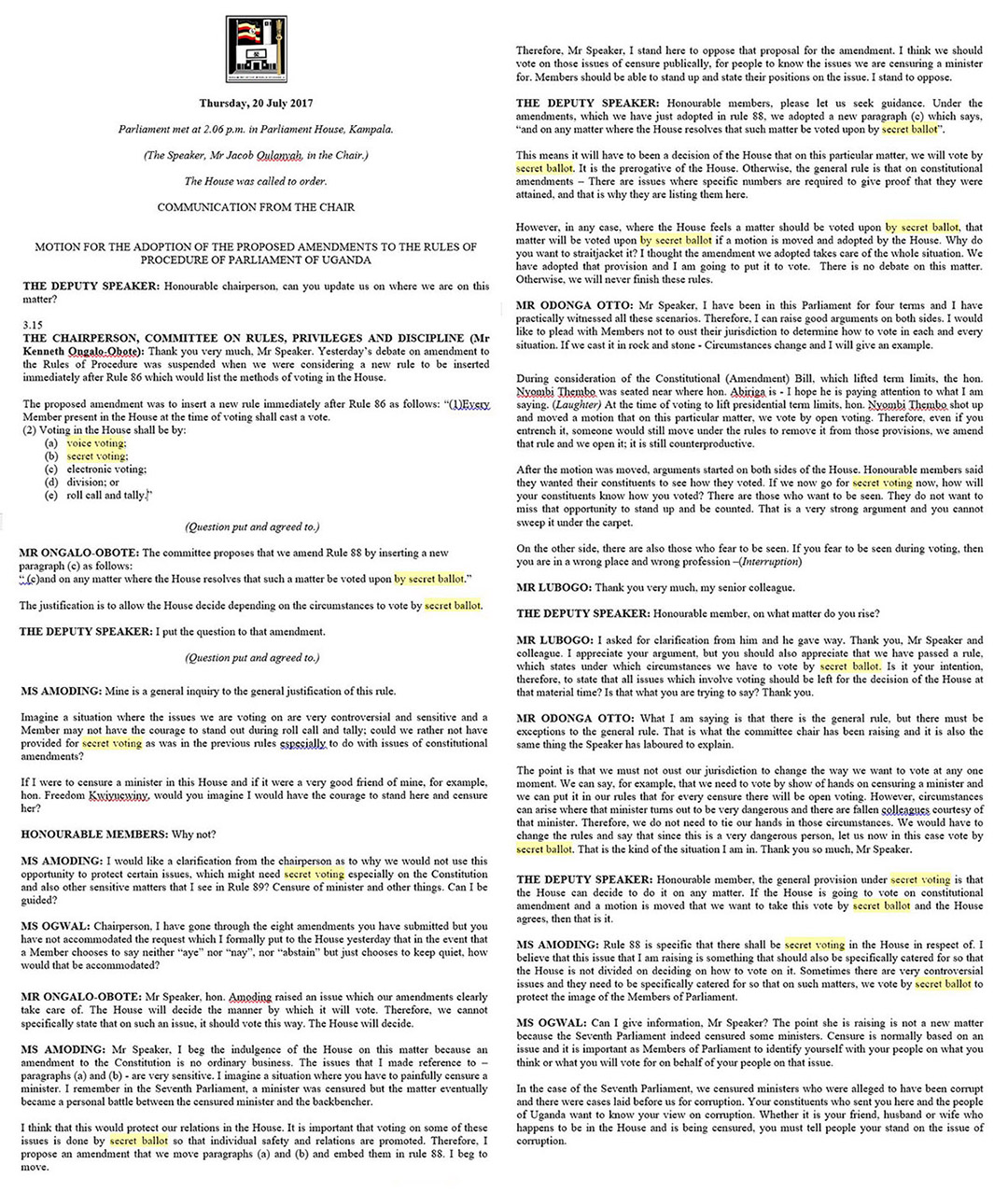

In places where open voting has been implemented, and especially in those countries where it is highly developed – such as the USA and also Norway - it has brought about considerable ills/drawbacks.Swedish Parliament 1899

Translation by Martin Söderholm

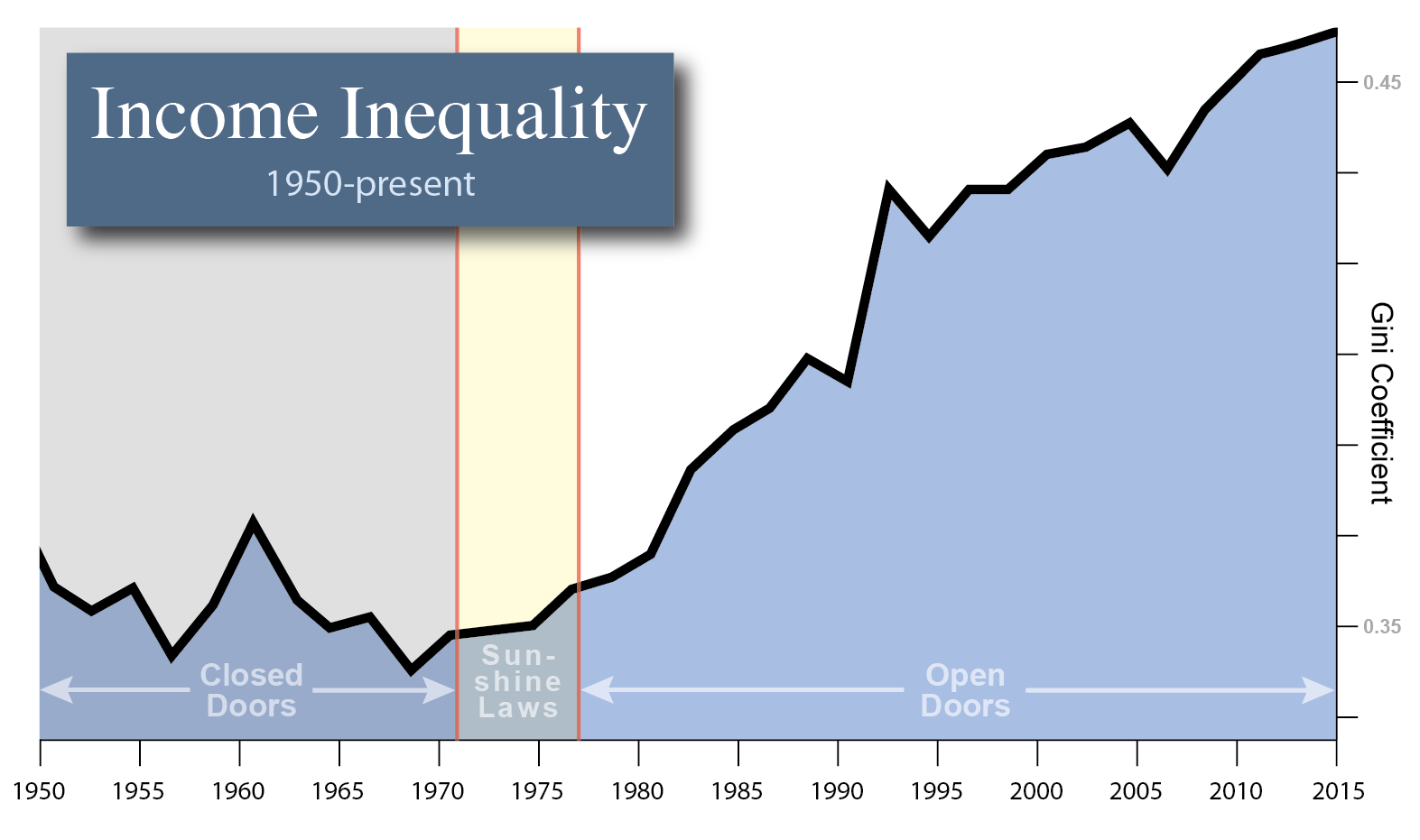

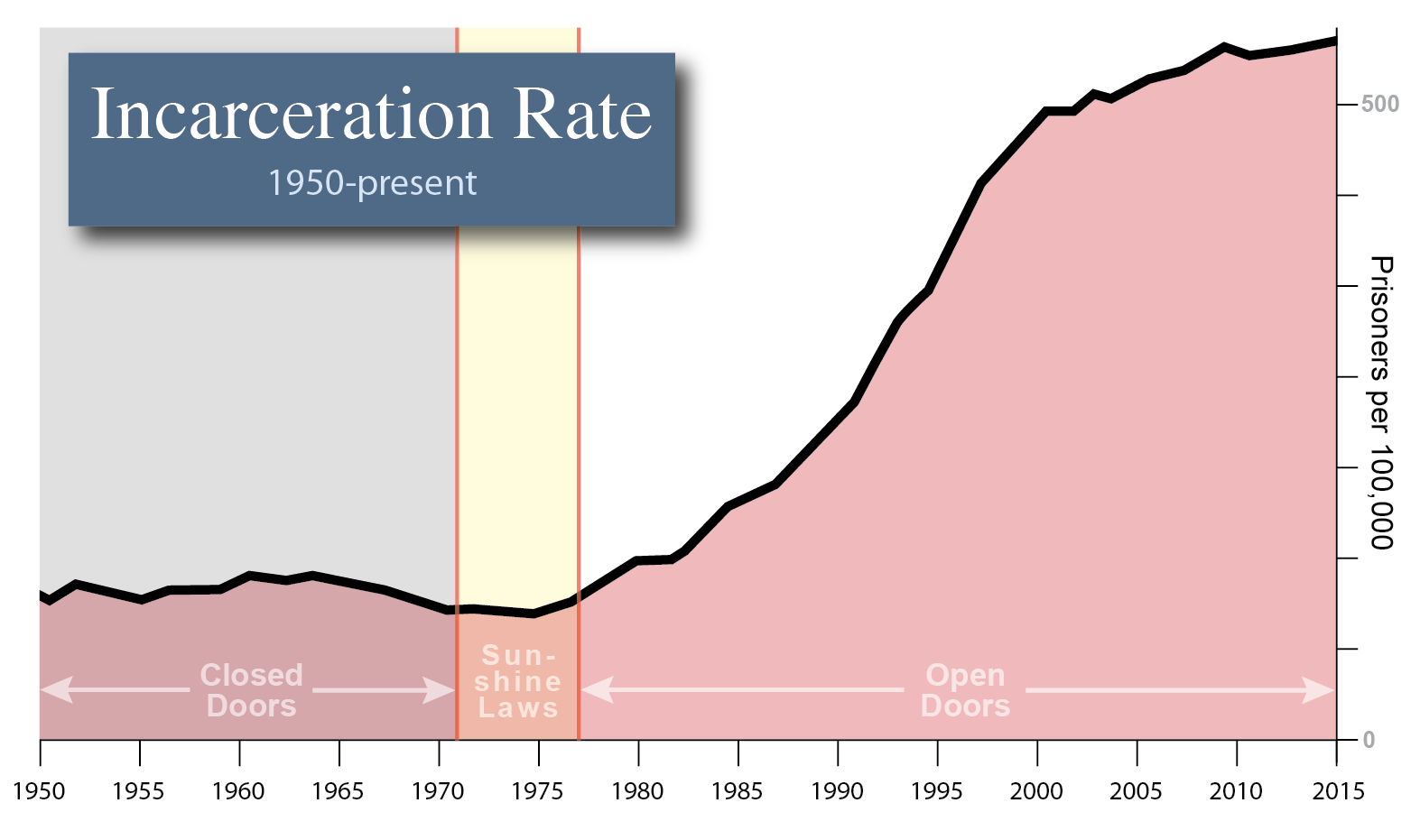

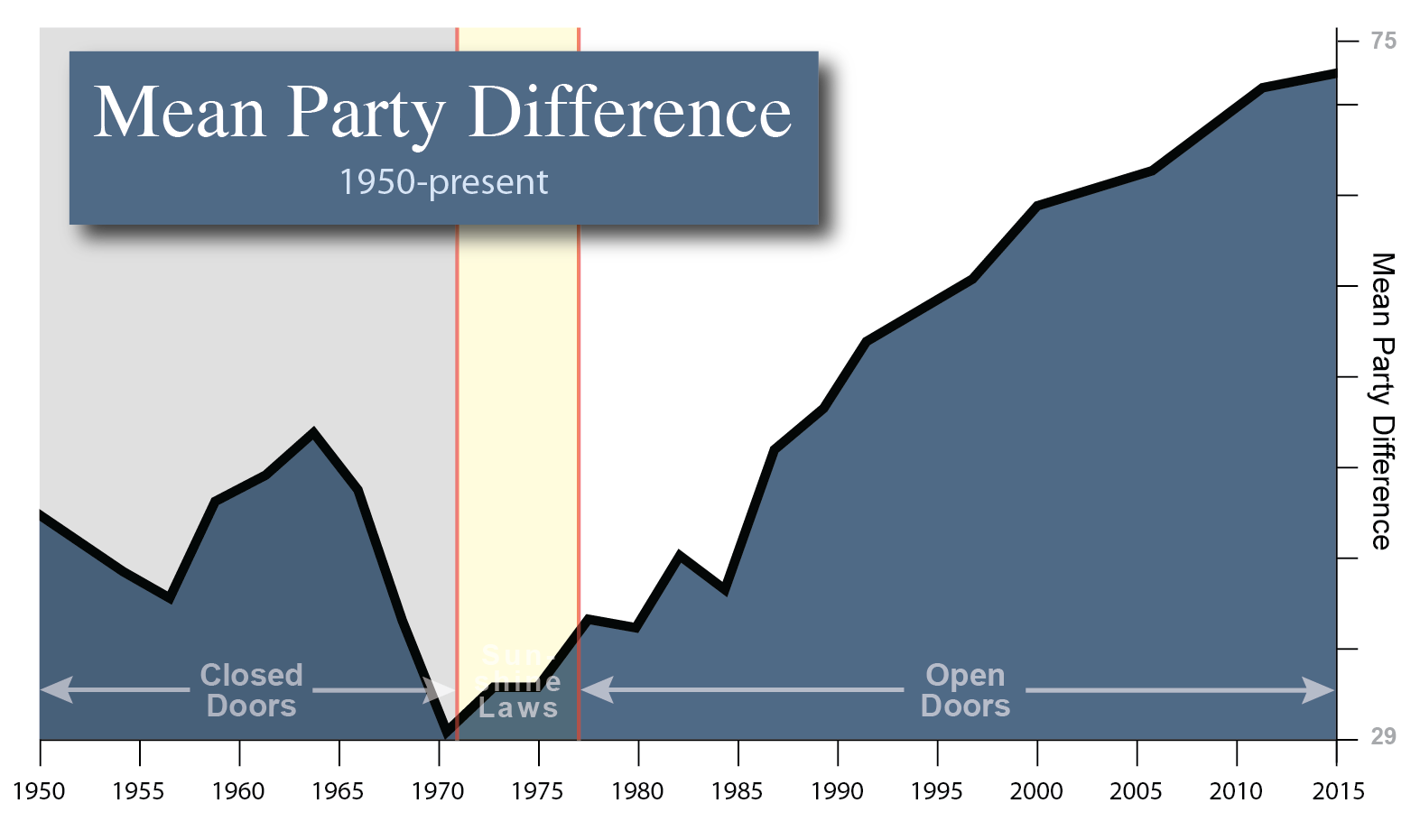

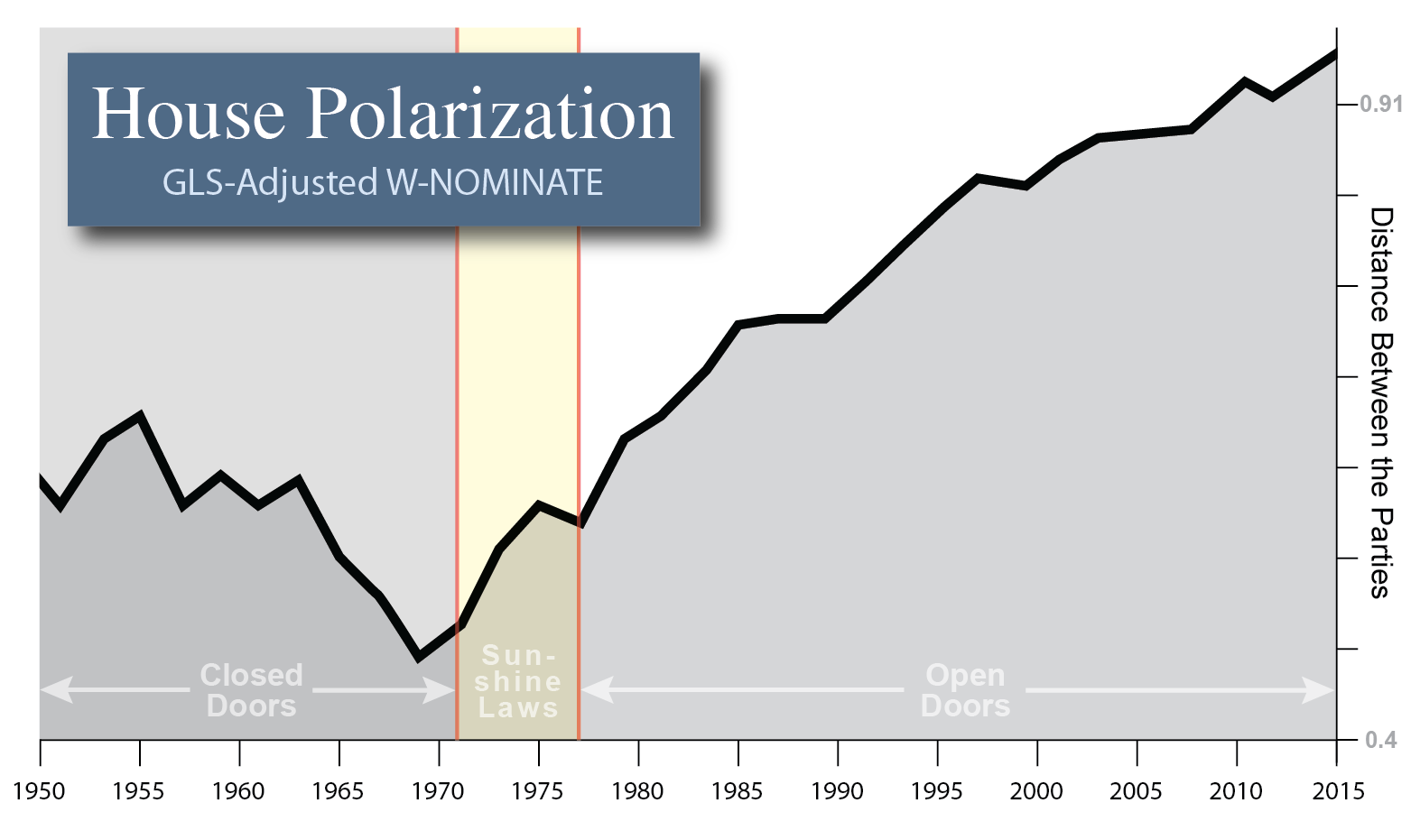

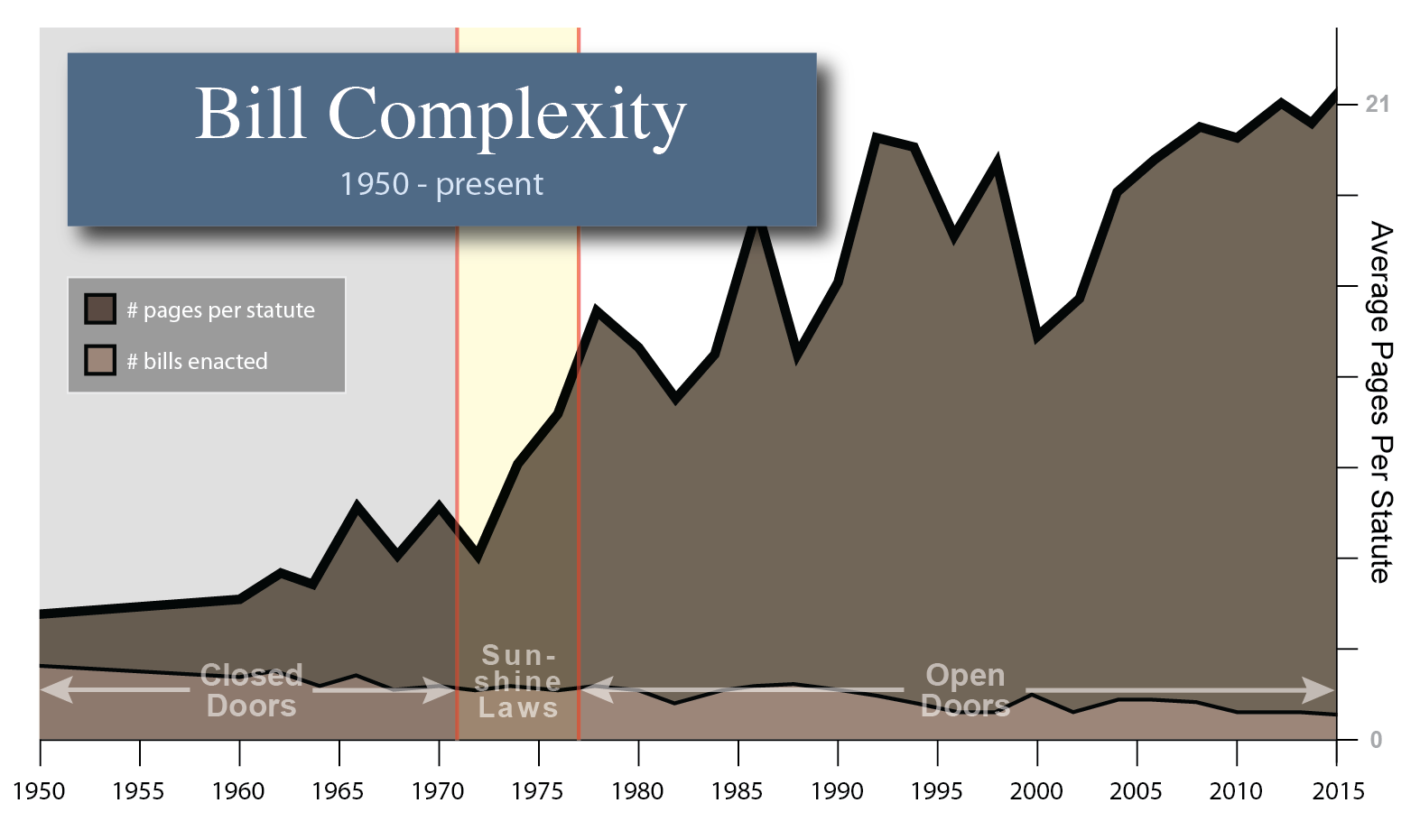

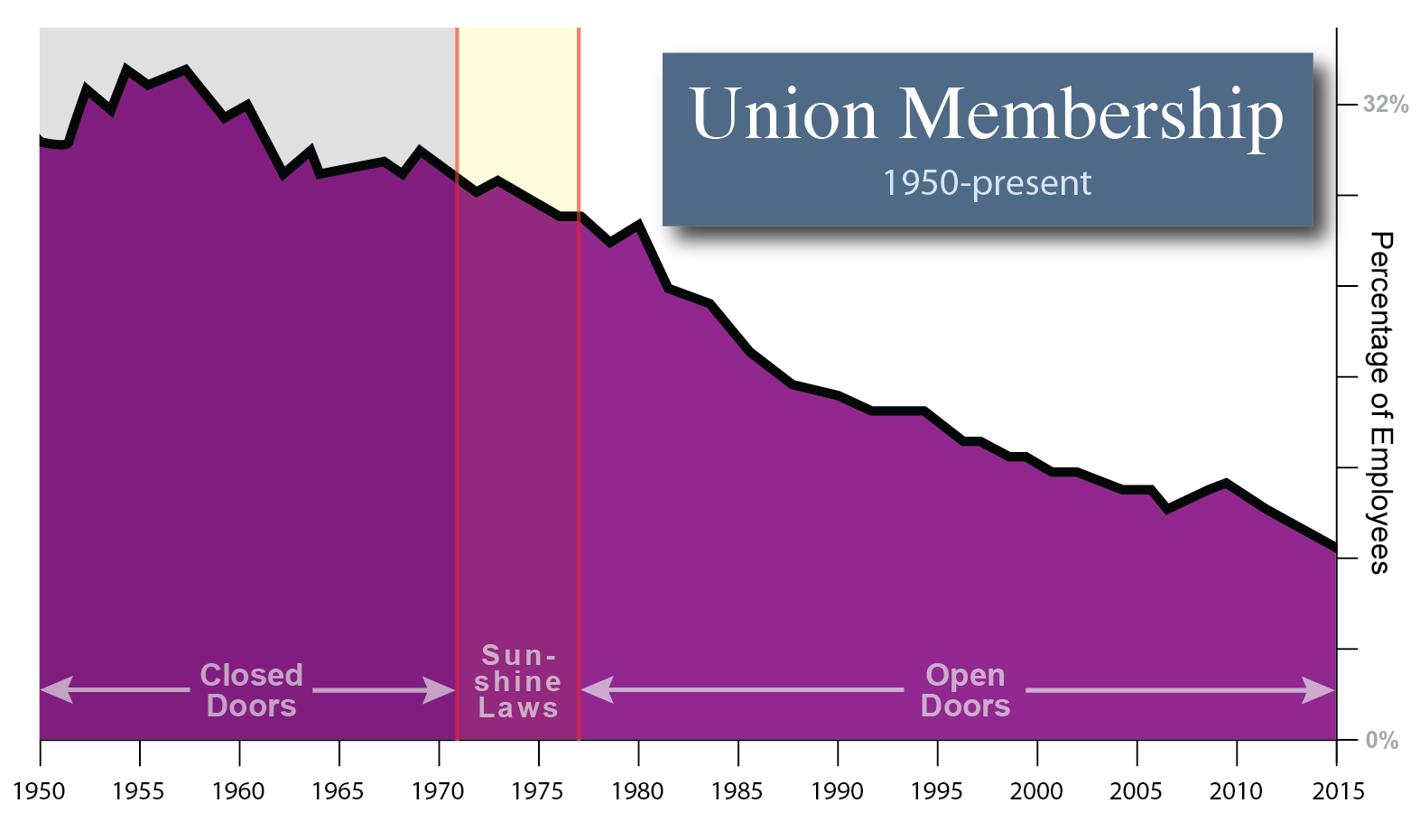

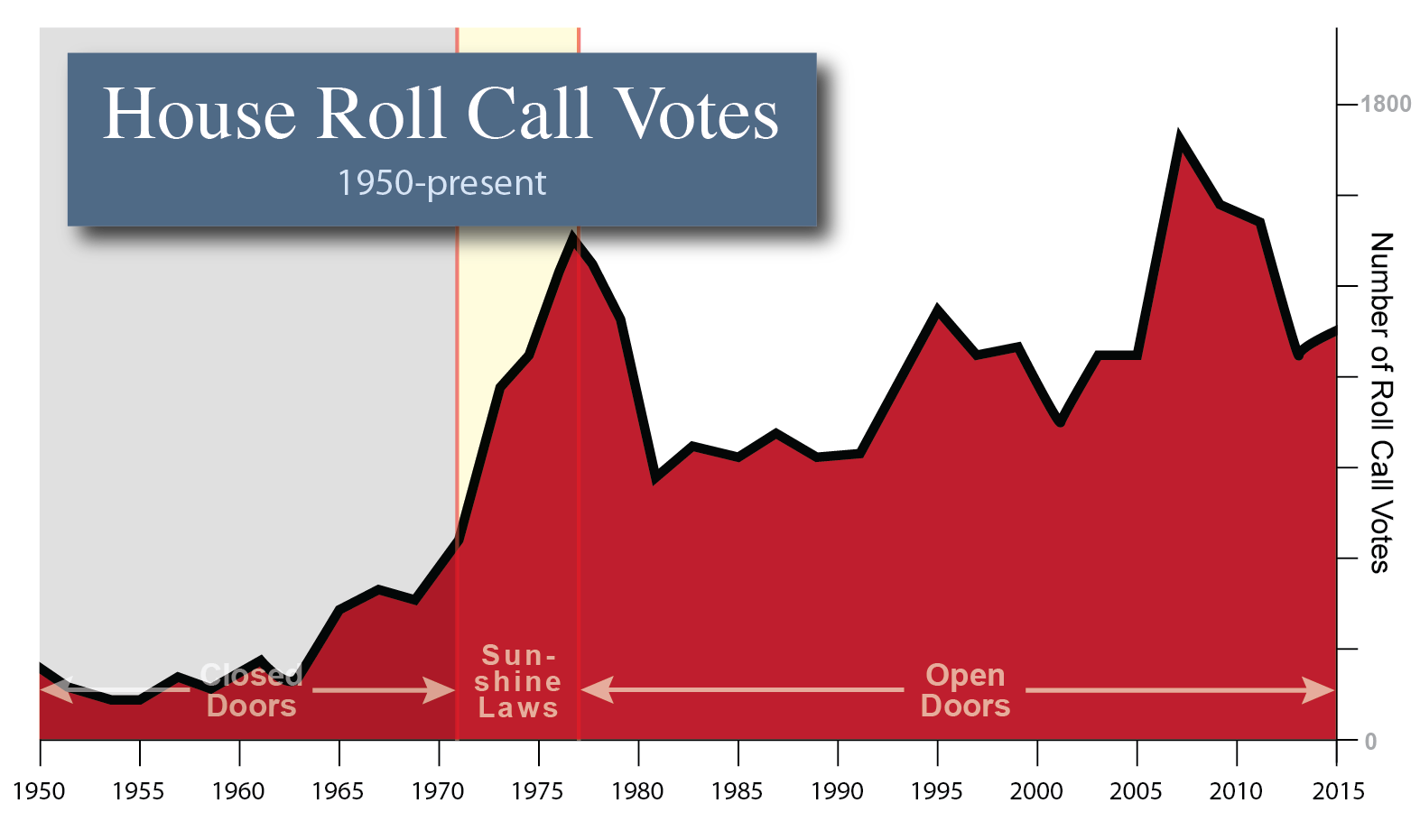

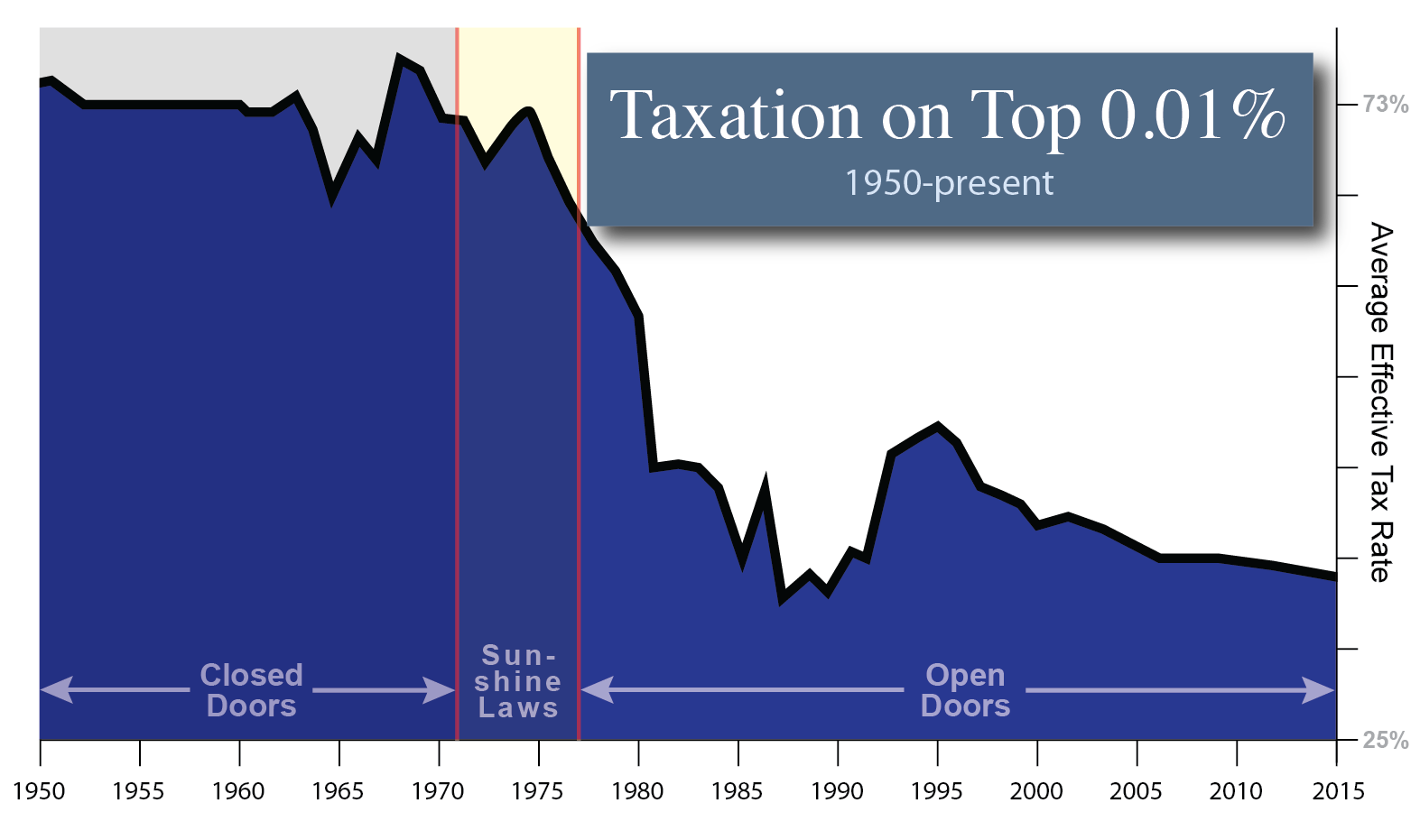

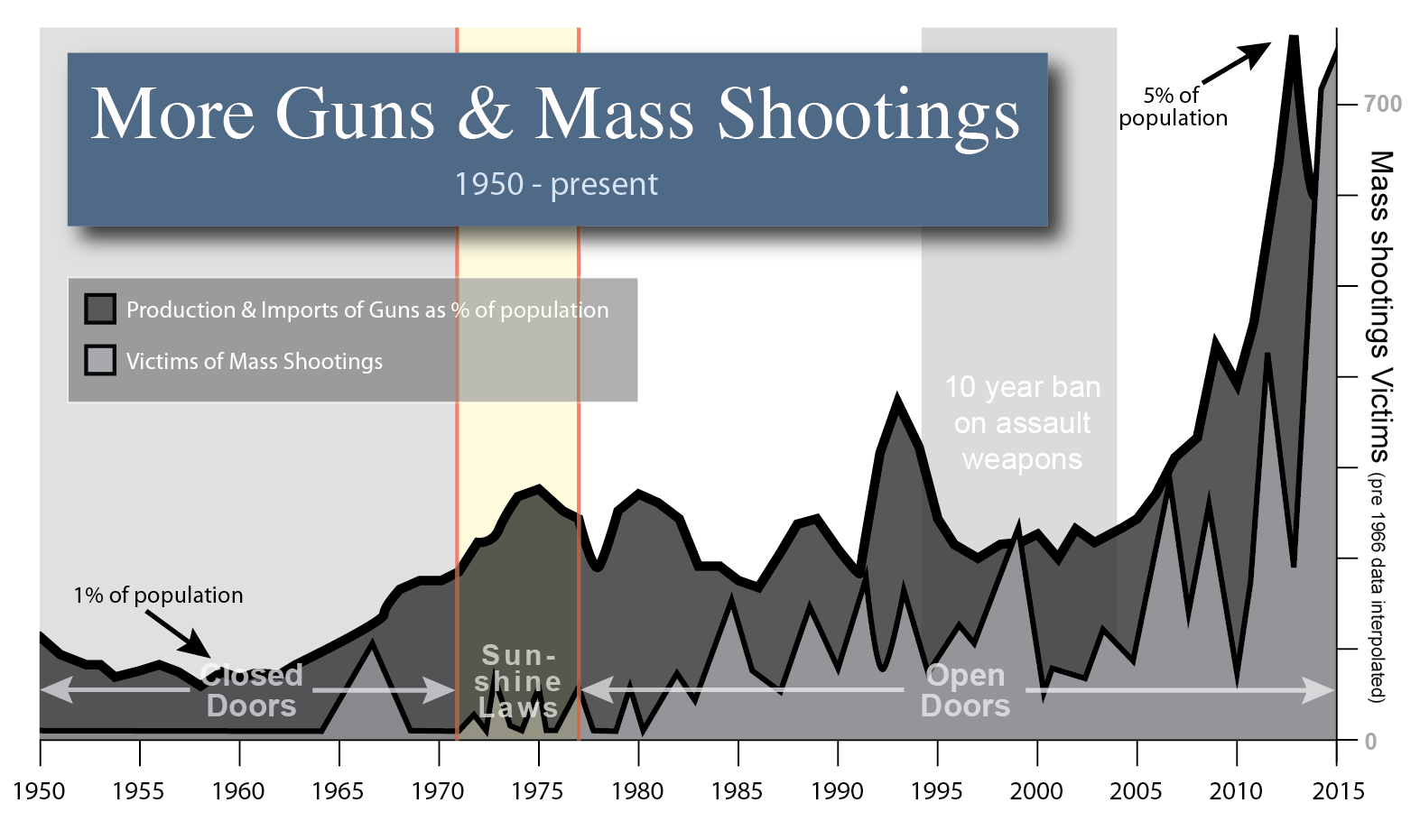

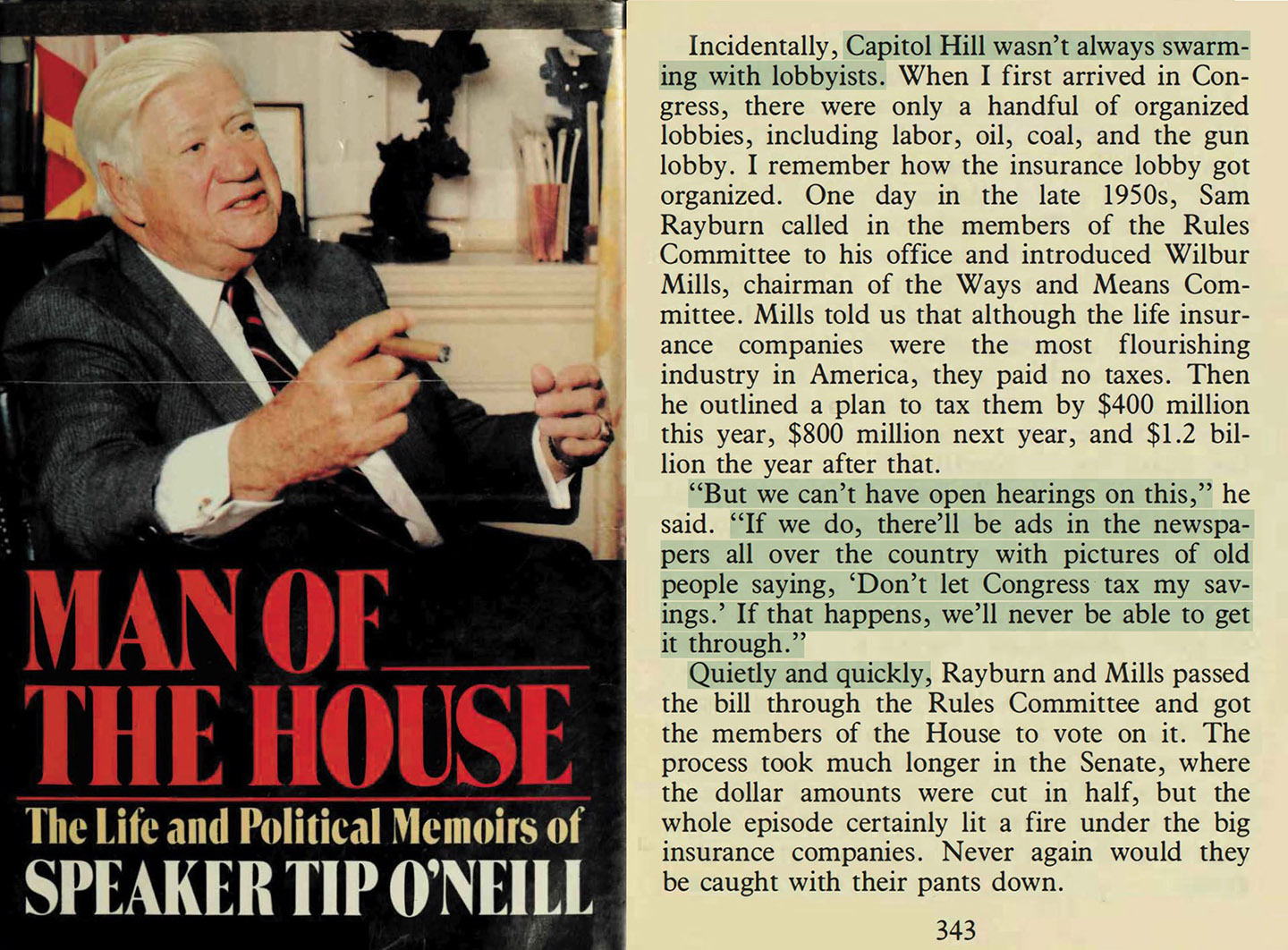

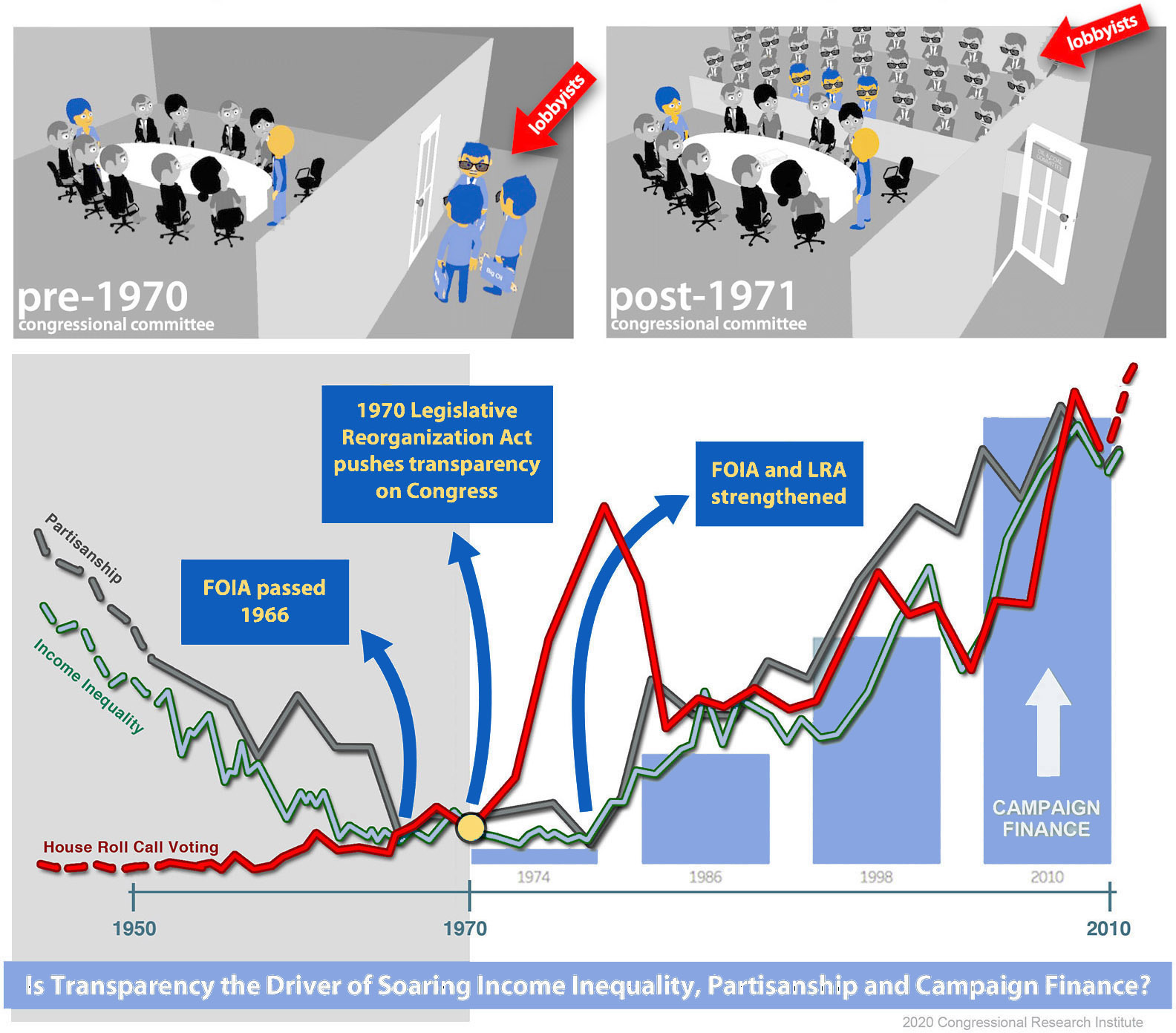

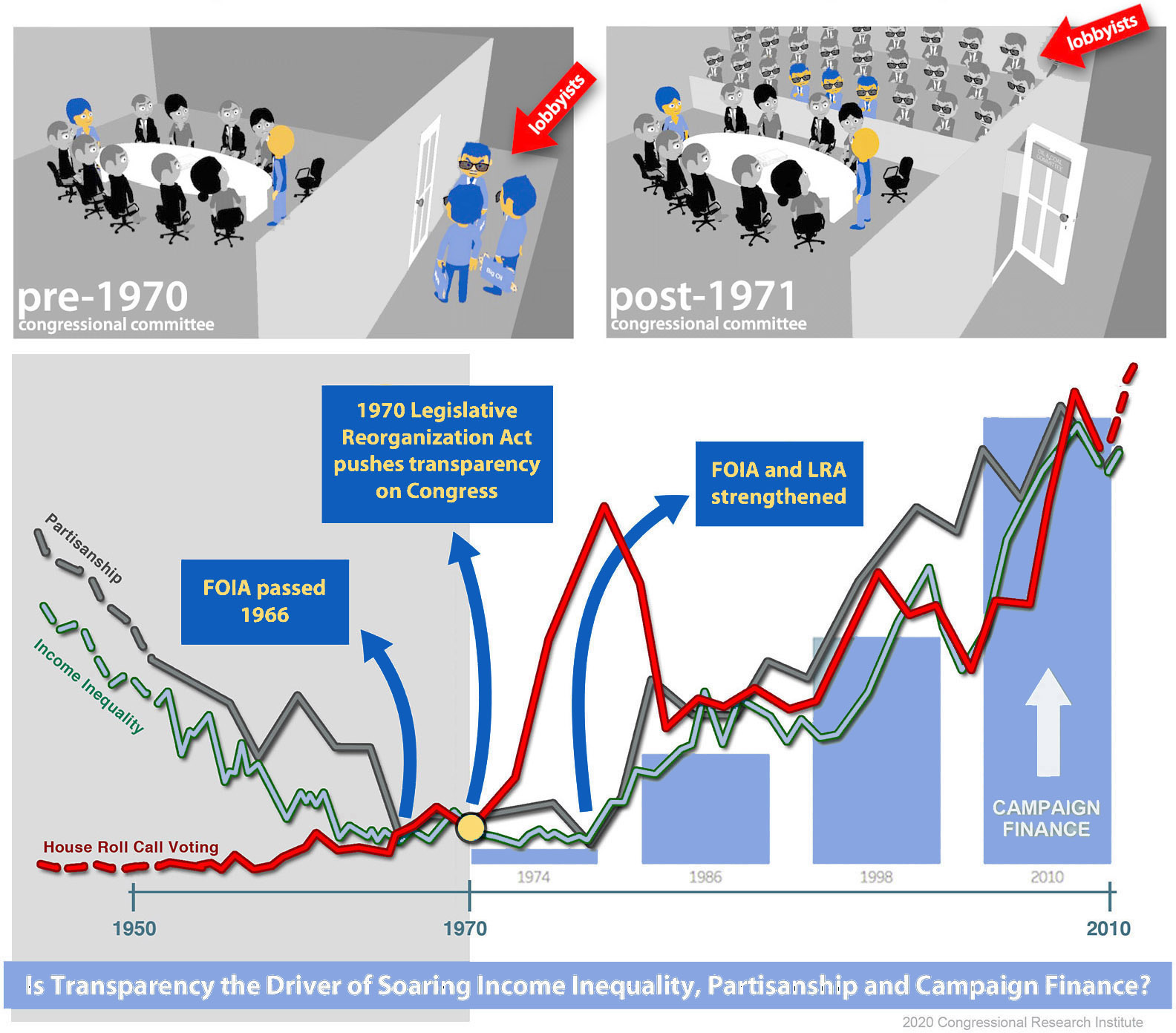

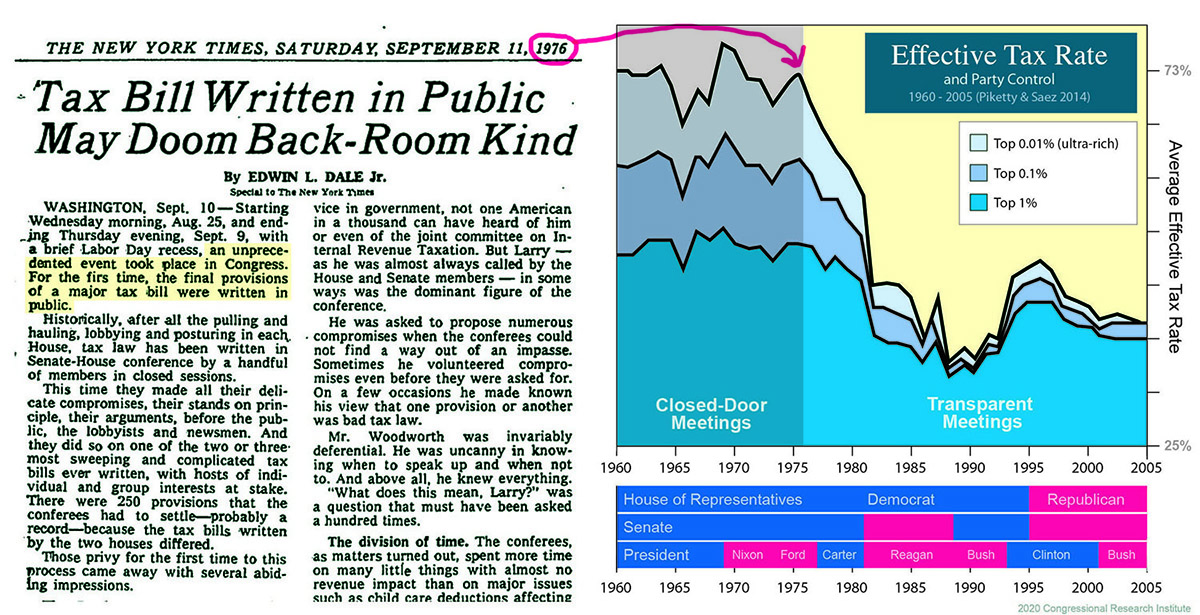

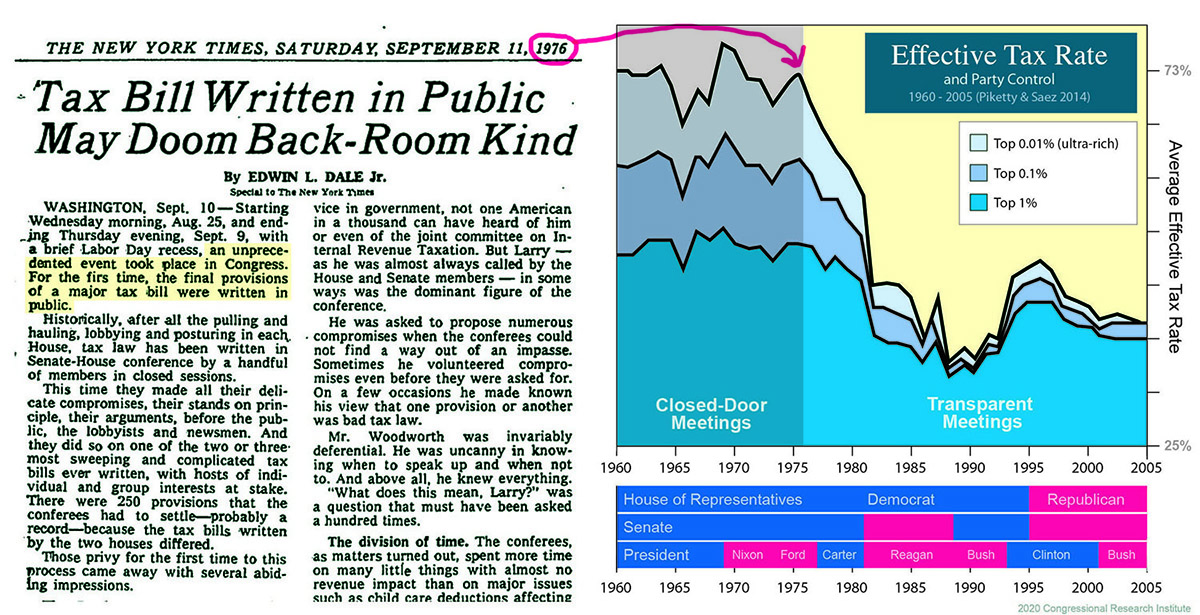

CRI 2020 - Is Government Transparency the Driver of Soaring Income Inequality, Partisanship and Campaign Finance?

CRI 2020 - Is Government Transparency the Driver of Soaring Income Inequality, Partisanship and Campaign Finance?

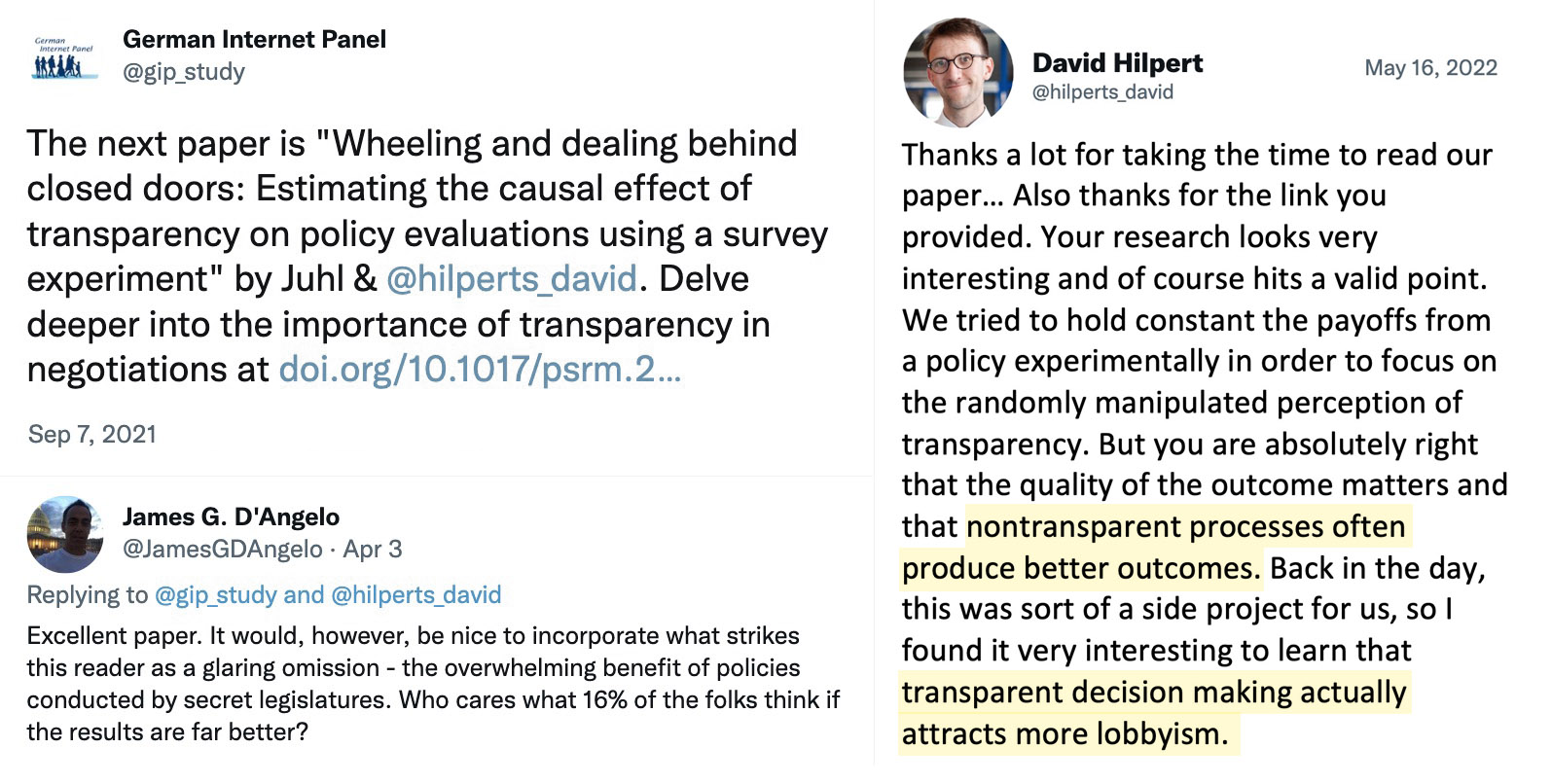

Greater political openness makes spending on lobbying more worthwhile, not less.Timothy Taylor 2019

When Special Interests Play in the Sunlight

We were a conquering army. We came here to take the Bastille. We destroyed [Congress] by turning the lights on.Rep. George Miller (D-CA) 2018

The Class of ‘74Full citation: Members of the Class believed that if they were able to make the institution and its procedures more transparent to the public, the House and American politics would change forever. “We were a conquering army,” recalled George Miller of California, “We came here to take the Bastille. We destroyed the institution by turning the lights on.”

Interest groups never call for secret negotiations.Barbara Koremenos 2010

Open Covenants, Clandestinely Arrived At

The idea that more transparency in government is always an unalloyed good is a dangerous populist illusion… The demand to see decisions being made is more often about giving reporters fodder for juicy stories or enabling groups to pressure decision-makers than helping voters make decisions.Francis Fukuyama 2015

The Limits of Transparency

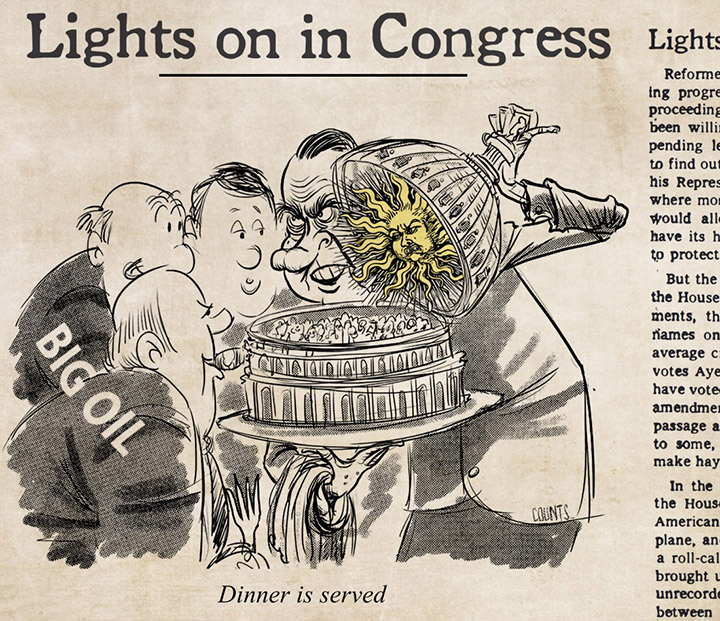

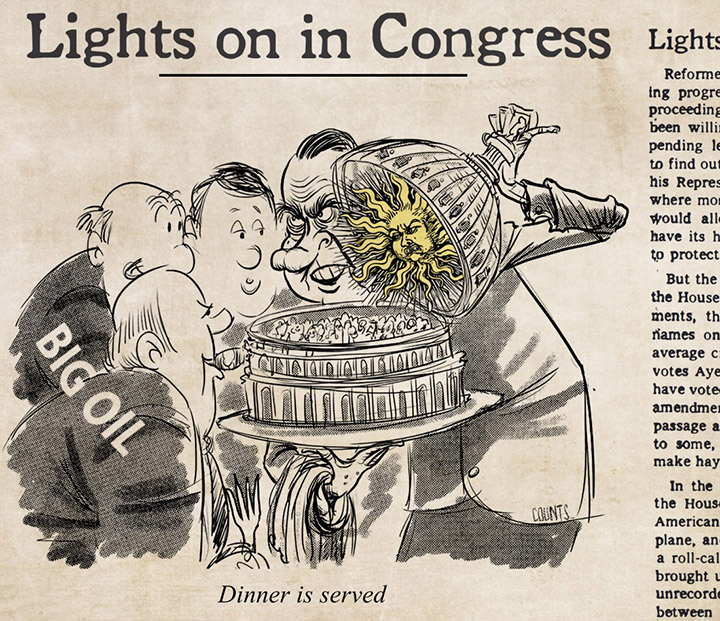

Dave Counts - Dinner is served

In 1970, President Nixon signed The Legislative Reorganization Act opening congressional committees to the glare of powerful interests.

Dave Counts - Dinner is served

Two decades later, after the advent of sunshine laws, we know better. Open markup sessions often give organized interests a powerful advantage over inattentive citizens, for they can monitor exactly who is doing what to benefit and to hurt them.Douglas Arnold 1990 (Princeton)

The Logic of Congressional Action

The groups that benefit most from fishbowl transparency and immediate access to details of ongoing negotiations are tightly organized groups seeking transfers to particular economic interests.Elizabeth Garrett & Adrian Vermeule 2006

Transparency in the Budget Process

There is a danger that too much transparency in many policy settings can weaken deliberation, violate privacy rights, and advantage well-organized interests that possess the resources and motivation to utilize opportunities to monitor government closely.Bruce Cain 2014 (Stanford)

Democracy More or Less

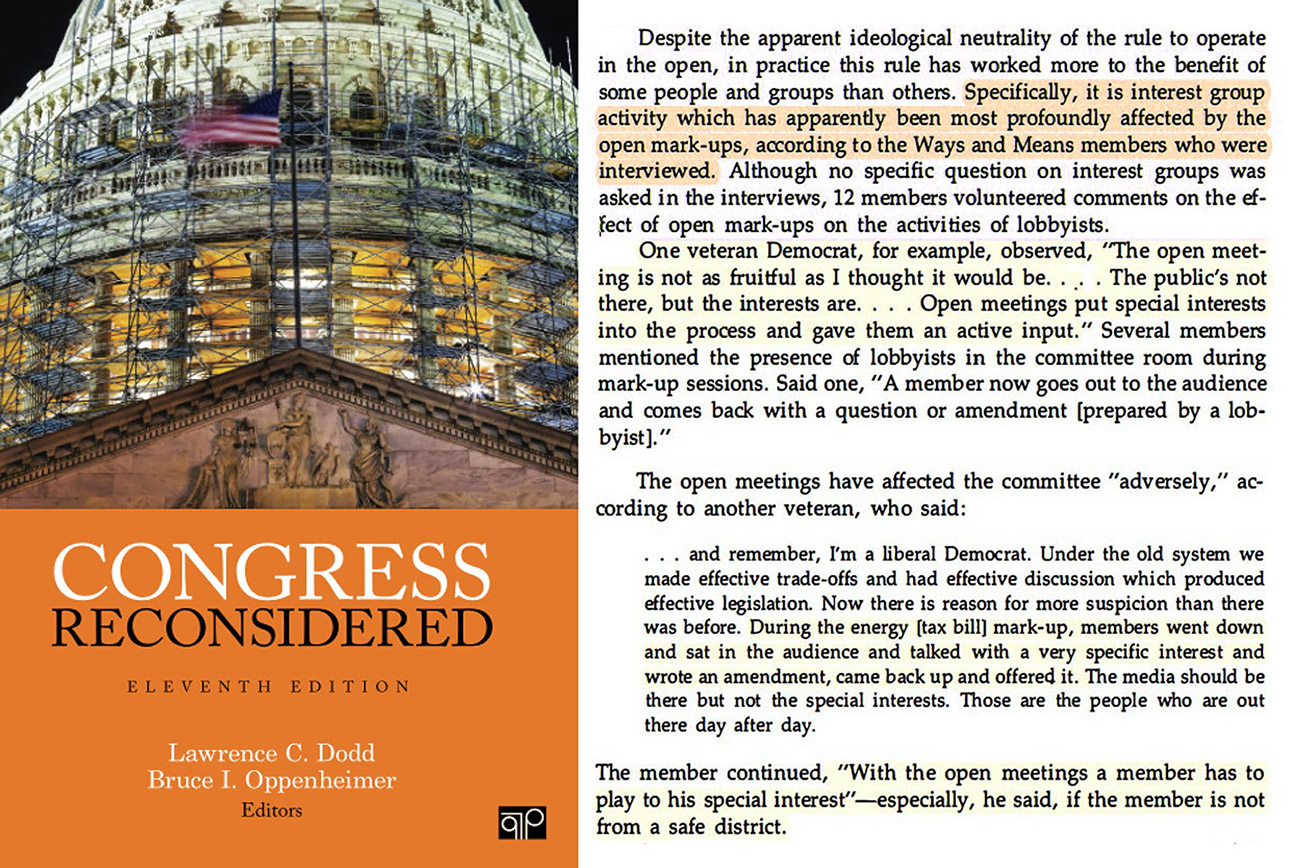

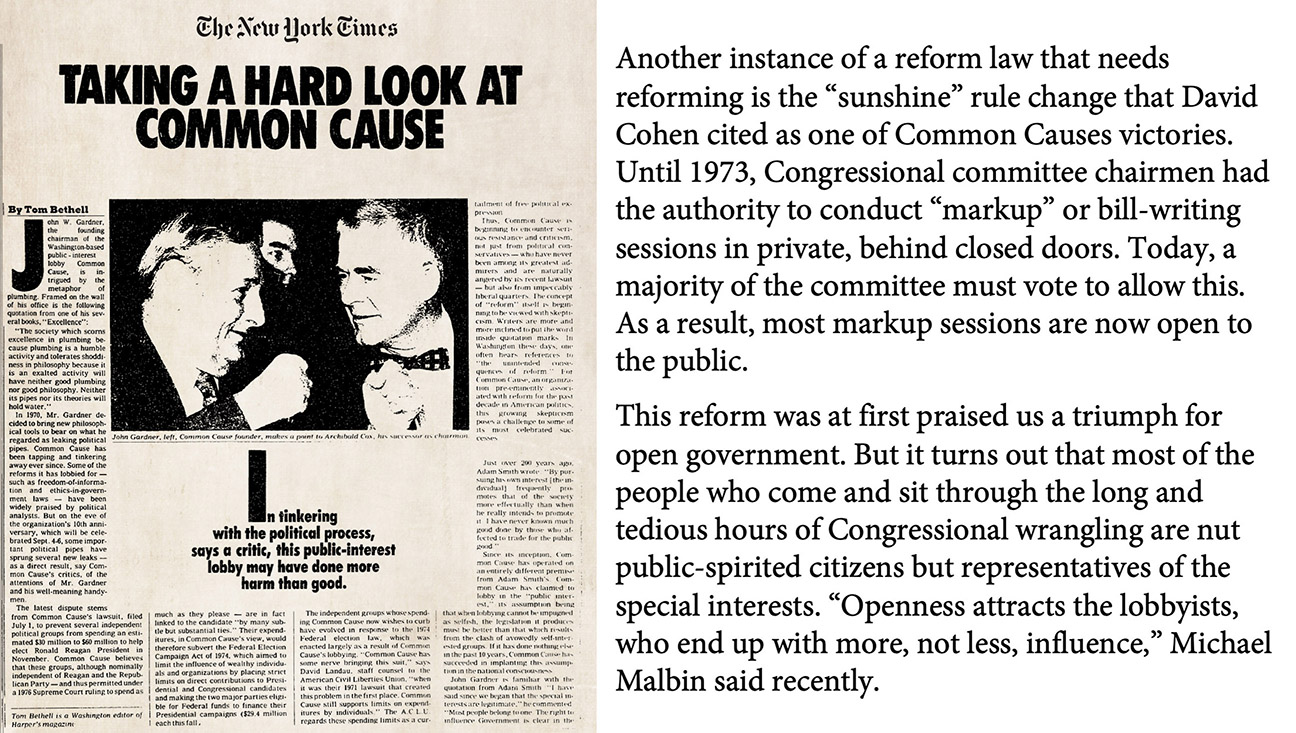

Consequences of Sunshine?

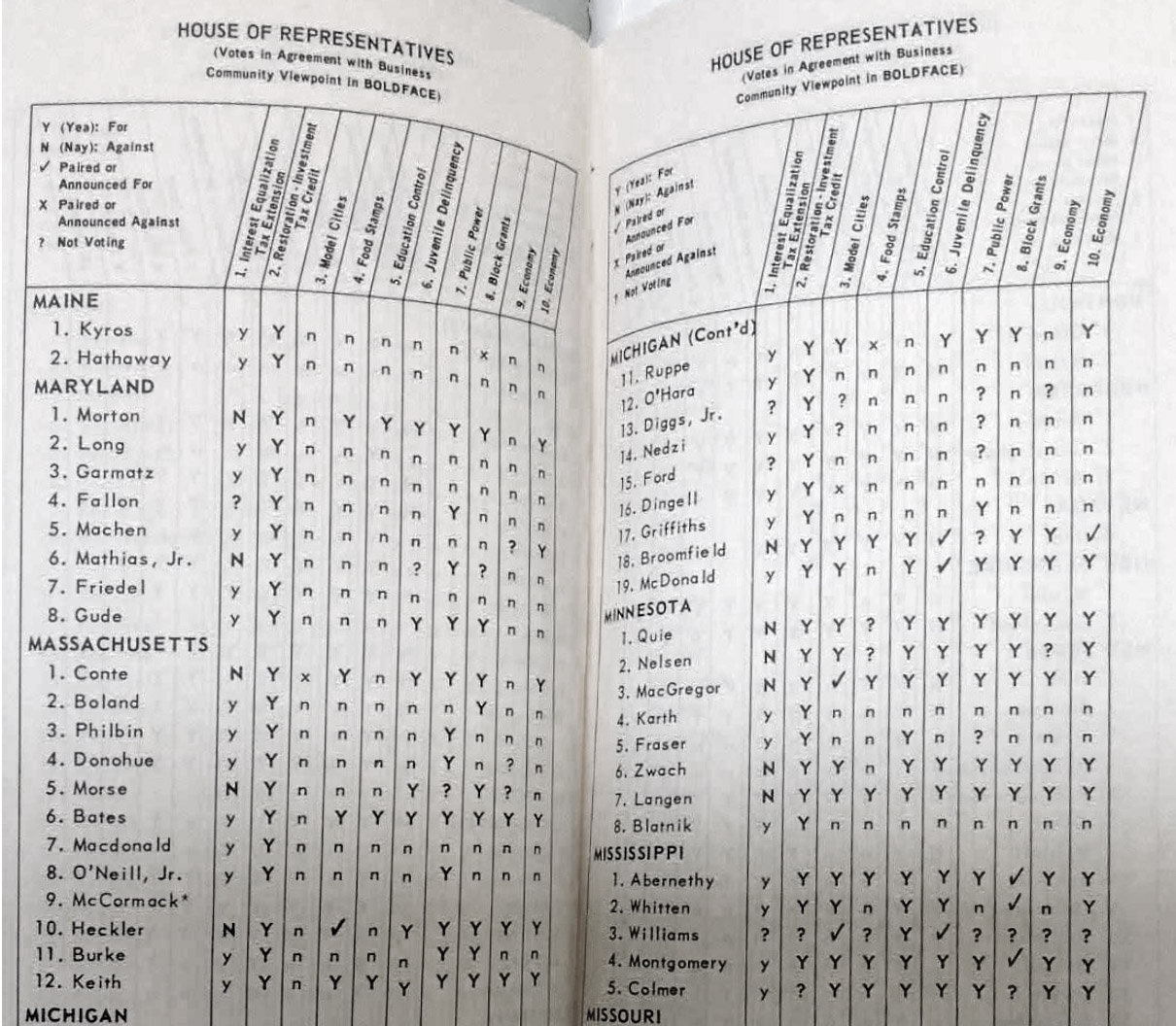

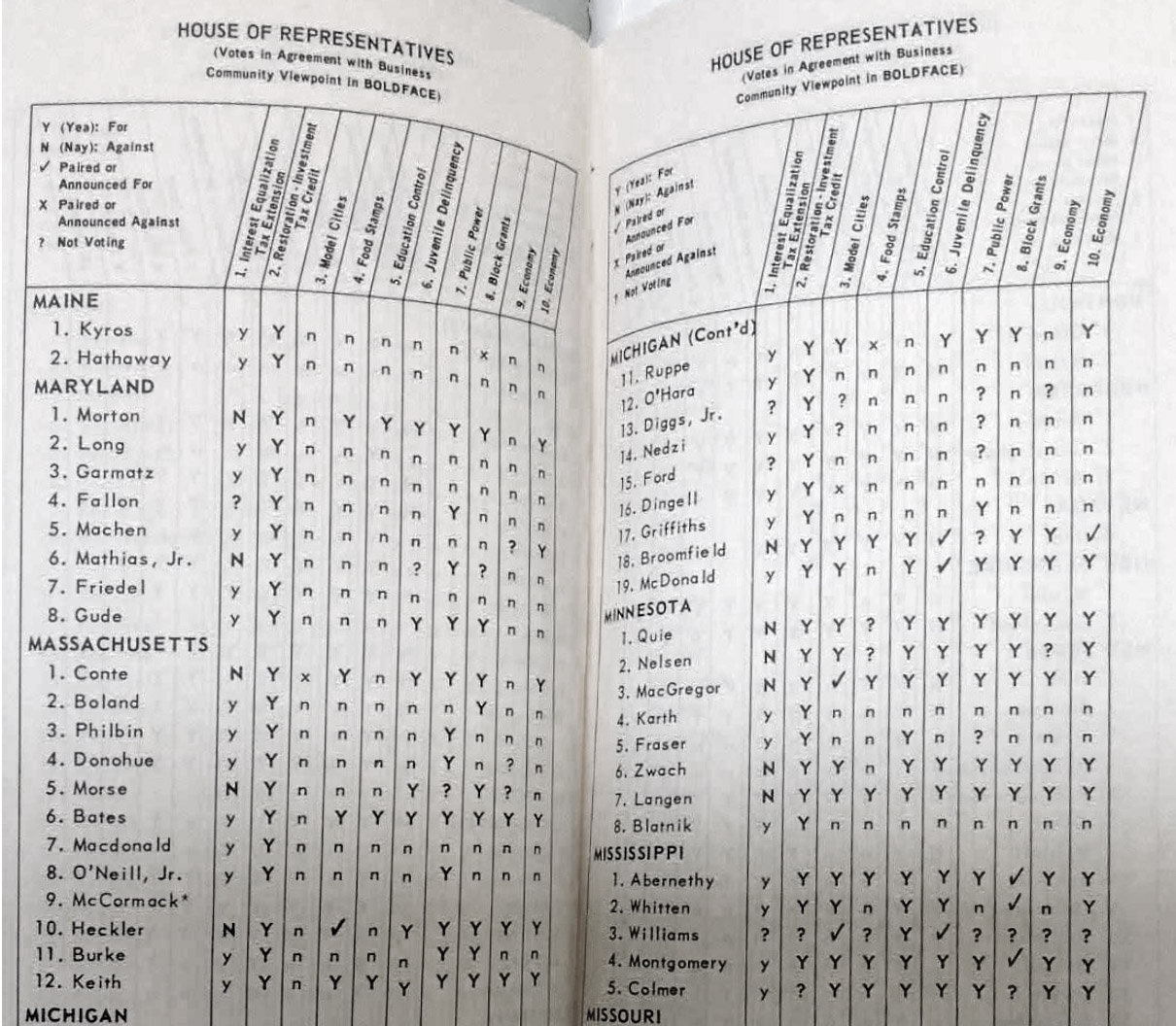

Interest groups have long treated voting records as the currency of legislators’ performance.John M. Carey 2009

Legislative Voting and Accountability

[Sunshine rules are] great for the lobbyists, but the members of Congress hate it. There in the back of the hearing room are all these lobbyists watching a markup session and giving a thumbs-up or a thumbs-down to specific wordings or provisions. It’s a fishbowl for them.Kay Lehman Schlozman & John T. Tierney 1983

More of the Same: Pressure Group Activity

As “sunshine” laws and rules opened markup sessions, hearings and conferences to the public, the lobbyist no longer was left hovering outside the closed door excluded from the action; rather he could be right there watching every move — in many cases suggesting legislative language and compromise positions.Congressional Quarterly 1982

The Washington Lobby

Recorded votes on amendments, and open knowledge of who introduced them, makes it easier for the lobbyist to monitor the action and apply pressure where most needed.Congressional Quarterly 1982

The Washington Lobby

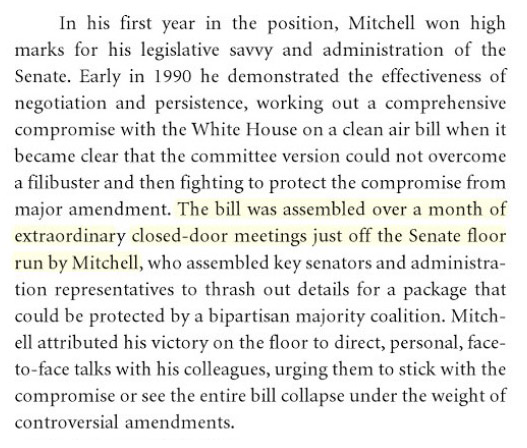

When he had to thrash out a new clean air bill, [George] Mitchell, the Senate majority leader, feared lobbying by auto, oil, coal and steel companies would be nasty. He was nervous about squabbling between Midwestern and Eastern senators. So Mitchell decided to hide the messiness behind closed doors. Sandy Grady 1990

Pollution of Reality [secret meetings environment]

By opening committee proceedings, and making members’ actions verifiable, the conditions for a viable market for votes are created.John Ferejohn 1999

Accountabiliy and Authority

Francis Fukuyama (Stanford) 2019 – Via Twitter

Francis Fukuyama (Stanford) 2019 – Via Twitter

It must be recognized that there is no way to open up the legislative process to the people without also opening it up to lobbyists and interest groups.Joseph Bessette 1994

Mild Voice of Reason

Full transparency can do great harm. If implemented without a notion of why some part of a system should be revealed, transparency can threaten privacy and inhibit honest conversation. “It may expose vulnerable individuals or groups to intimidation by powerful and potentially malevolent authorities.”Mike Ananny & Kate Crawford 2016

Seeing without knowing: Limitations of the transparency ideal

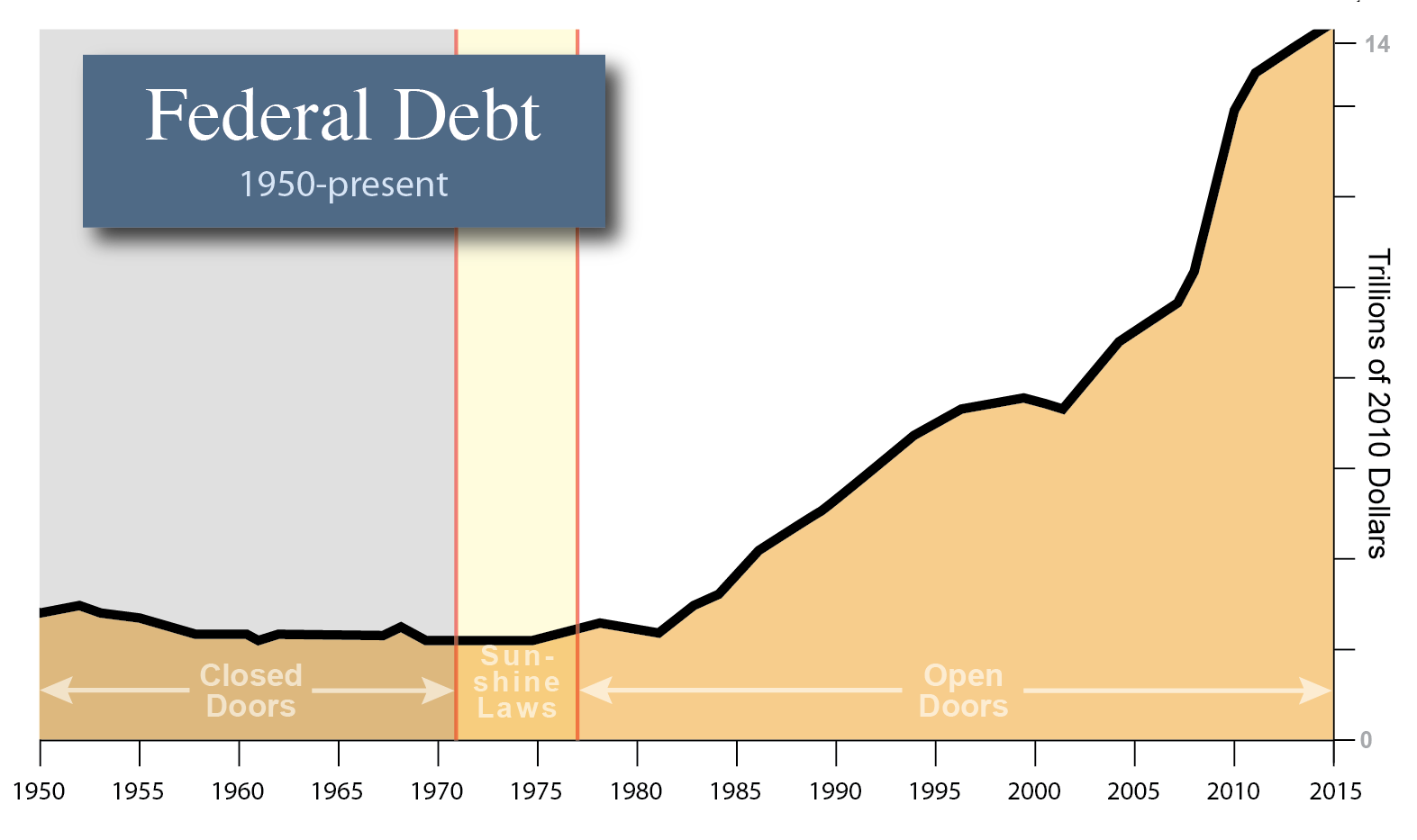

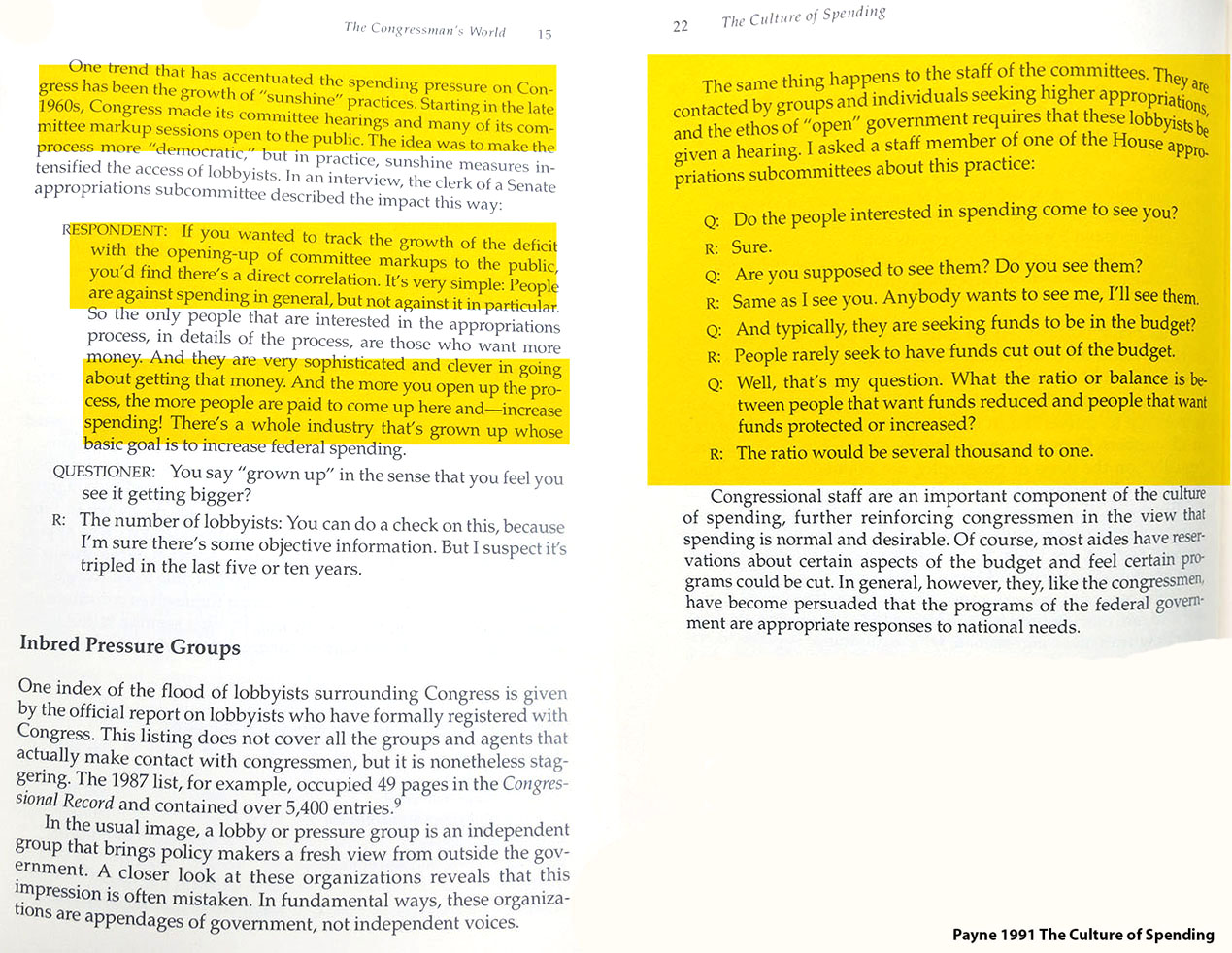

If you wanted to track the growth of the deficit with the opening-up of committee markups to the public, you’d find there’s a direct correlation.James L. Payne 1991 (interview)

Culture of Spending

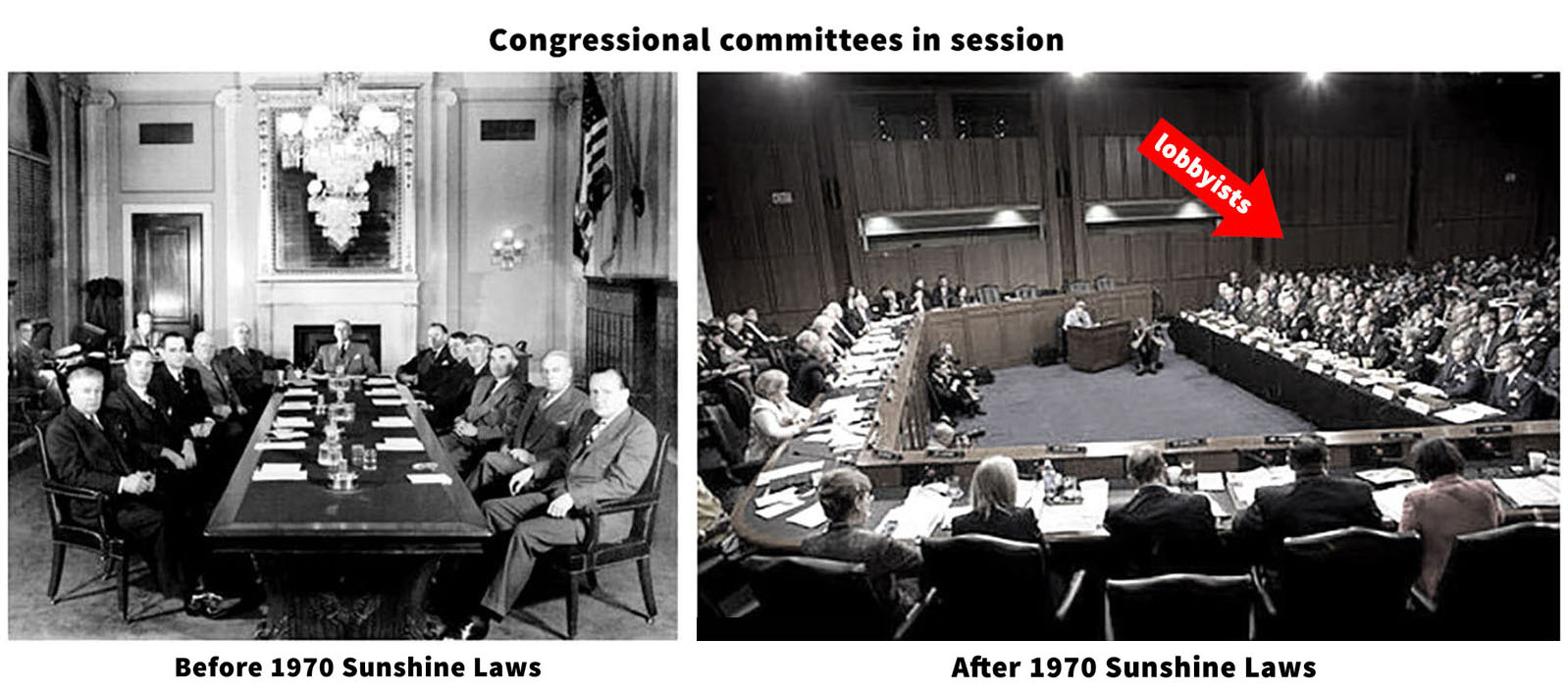

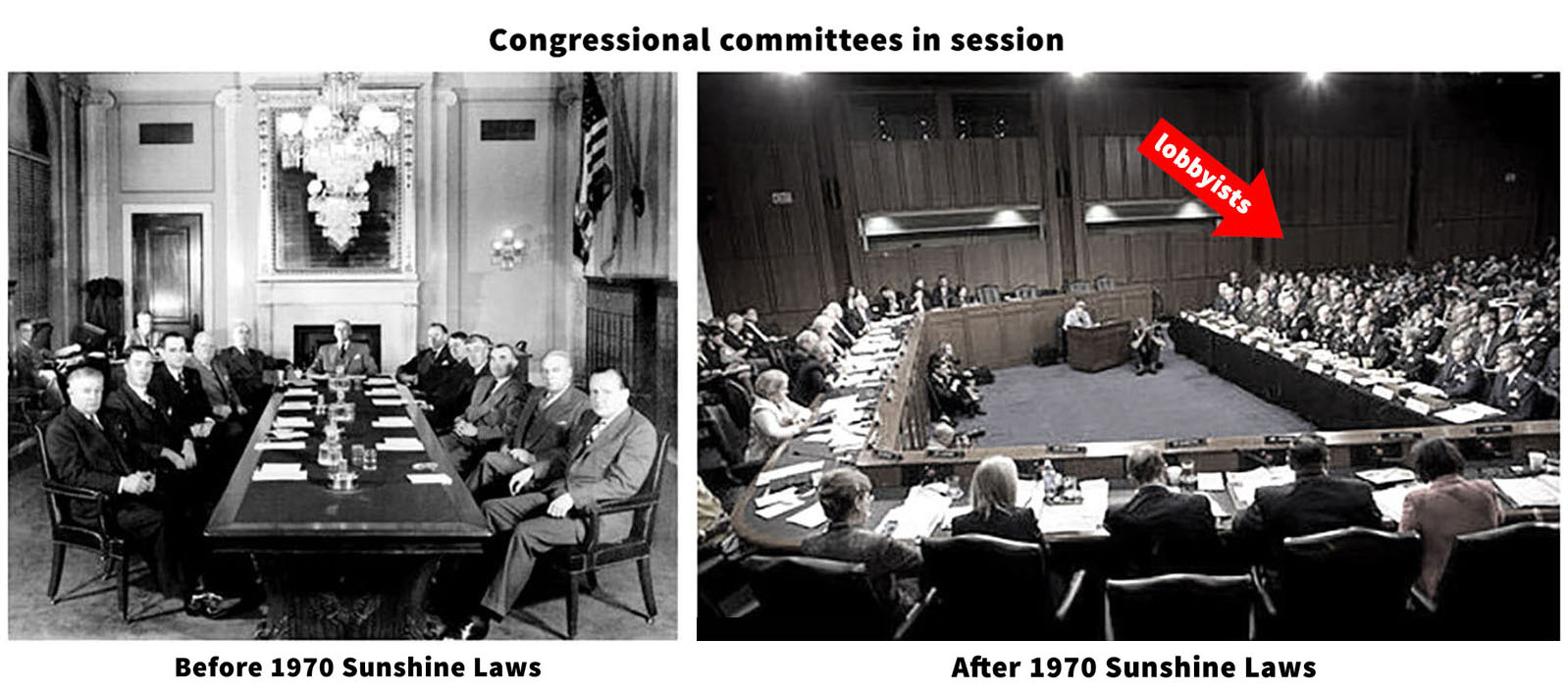

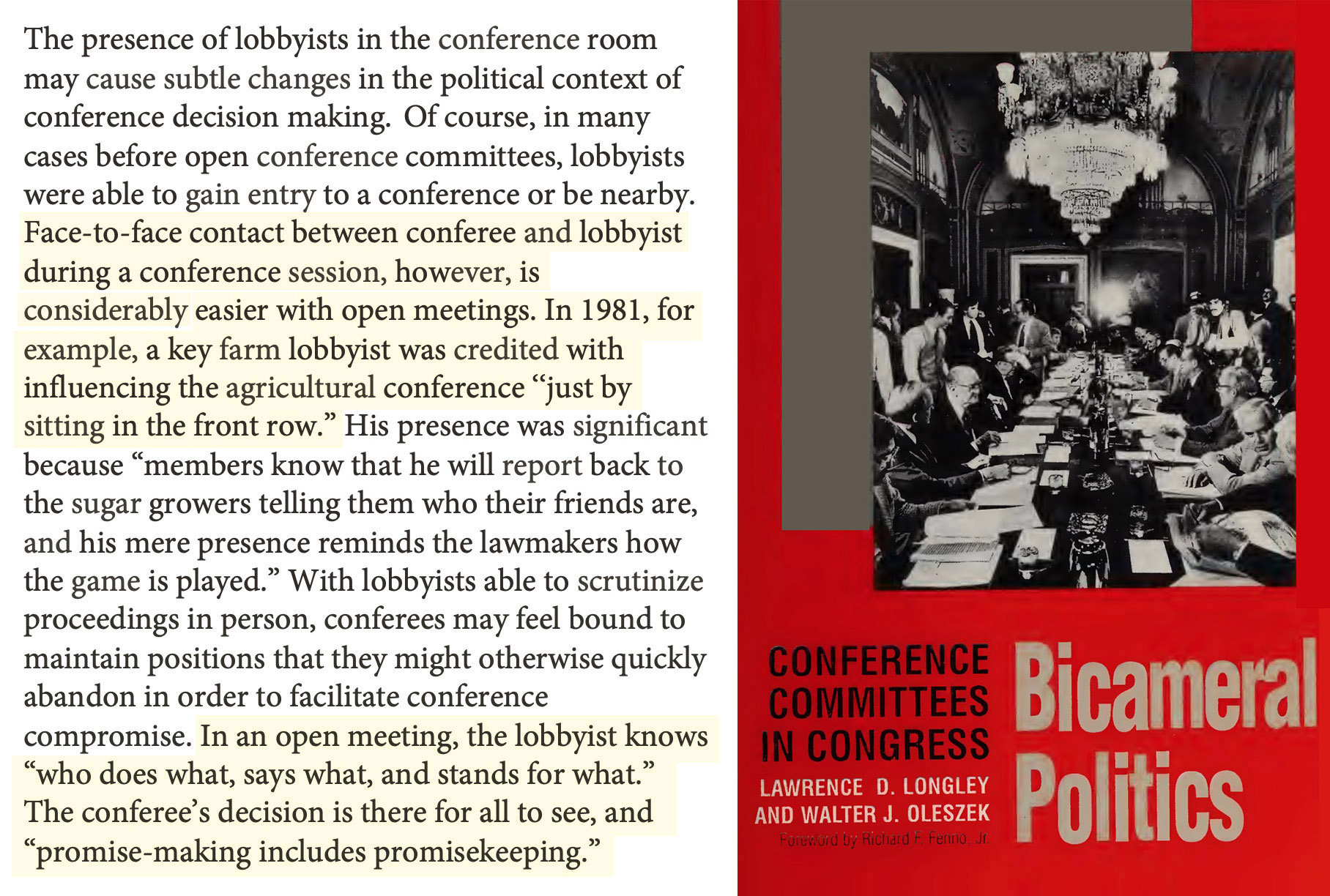

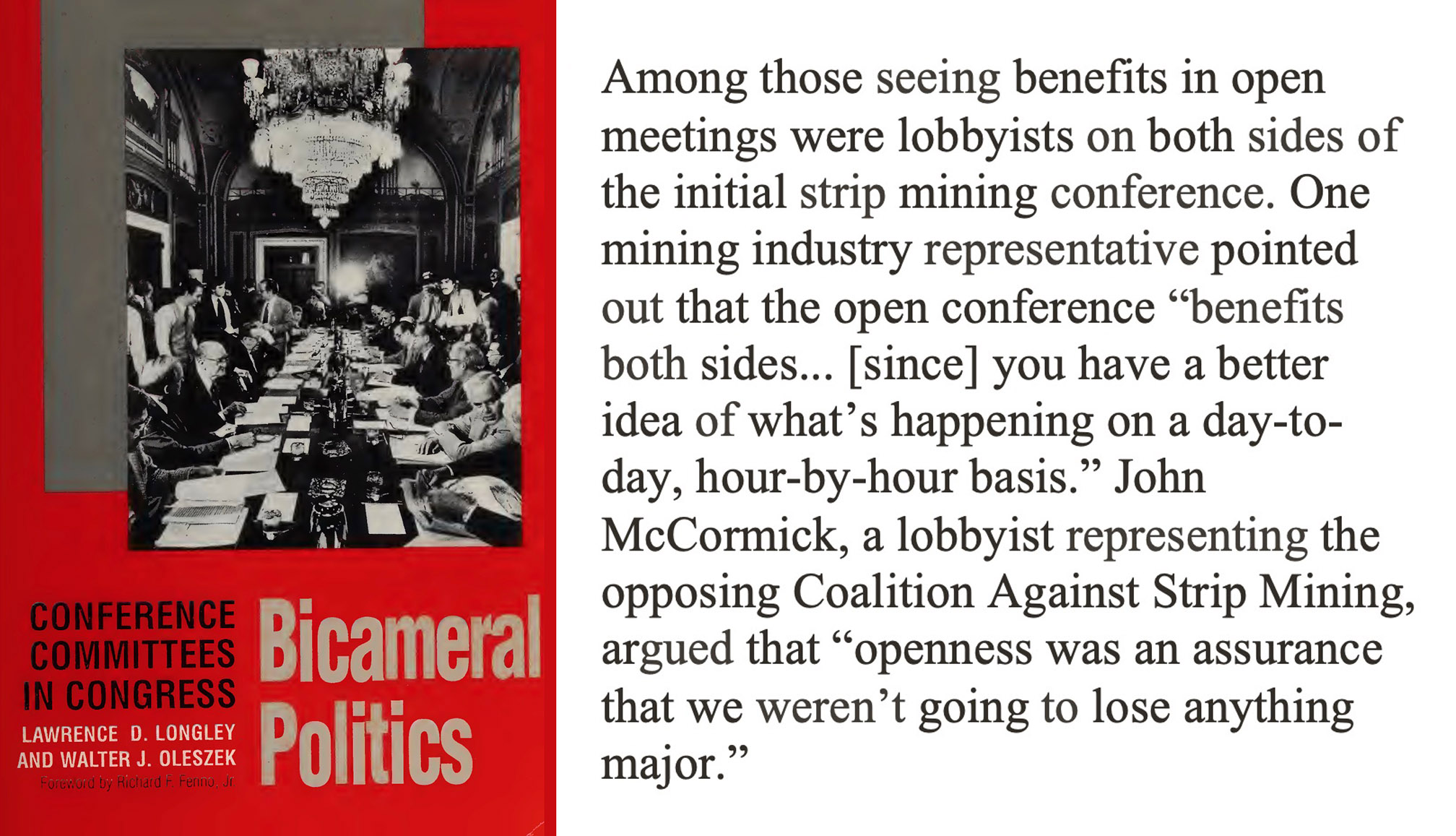

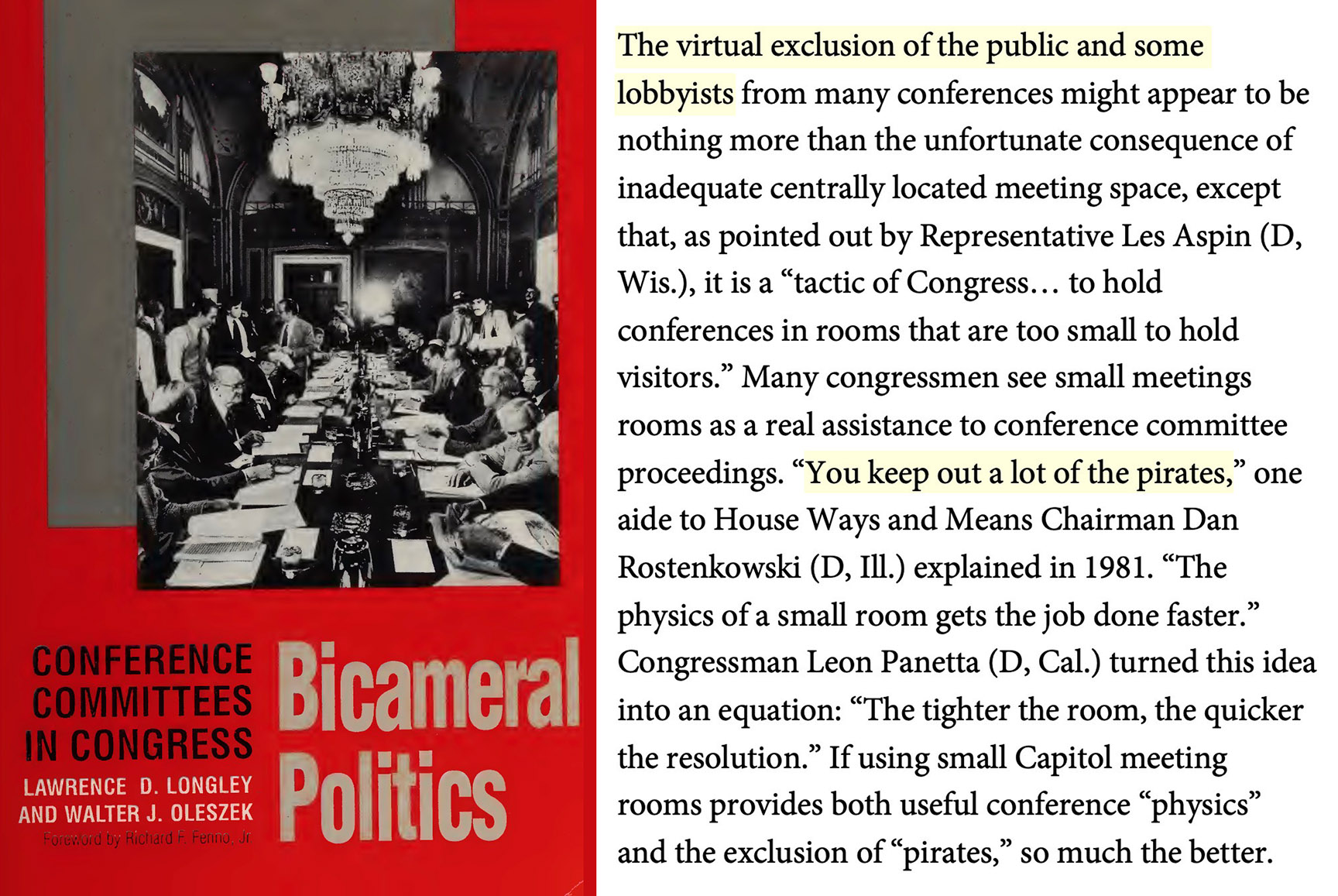

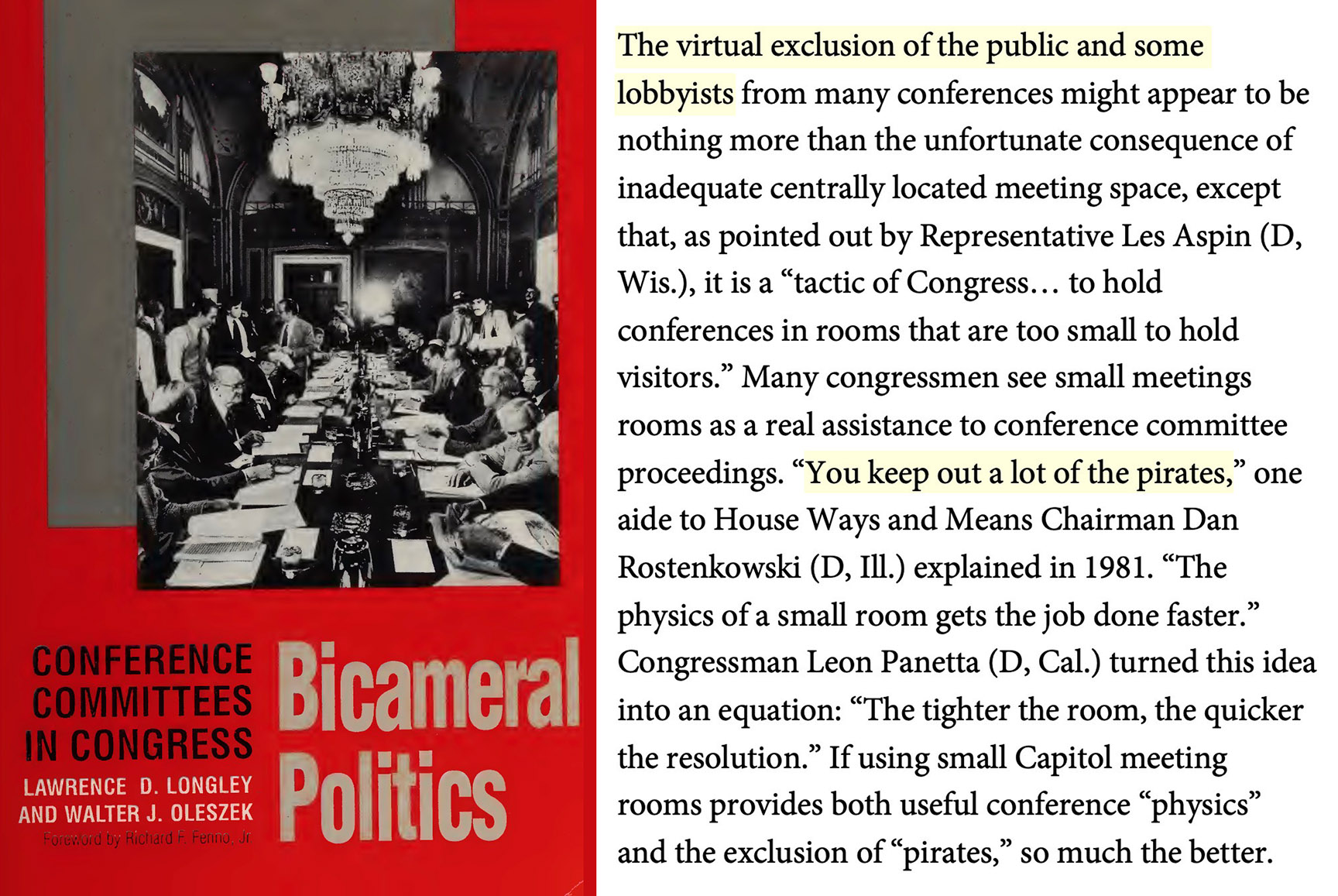

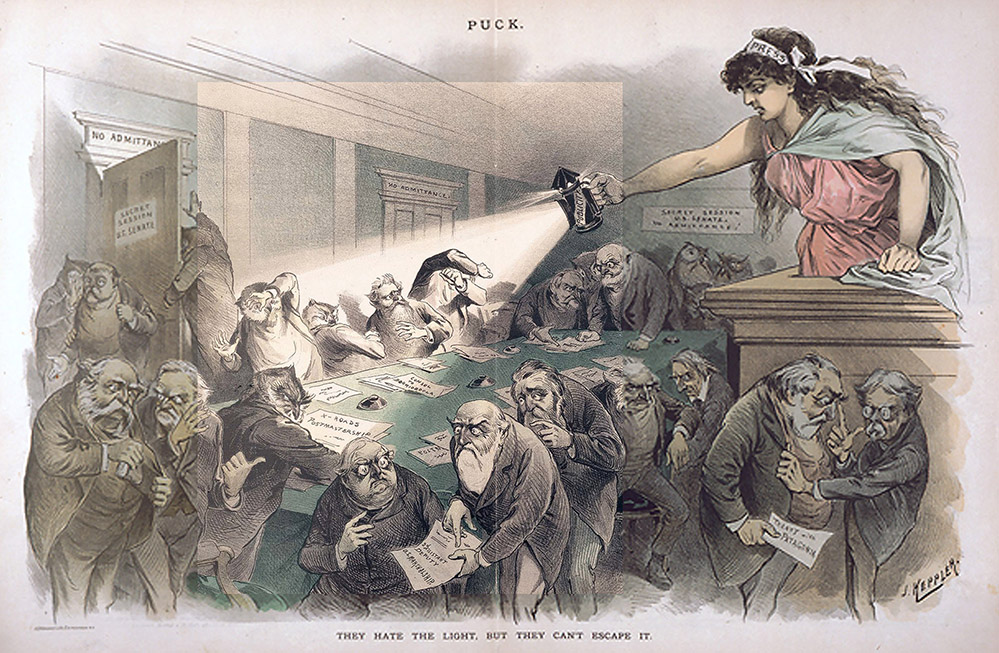

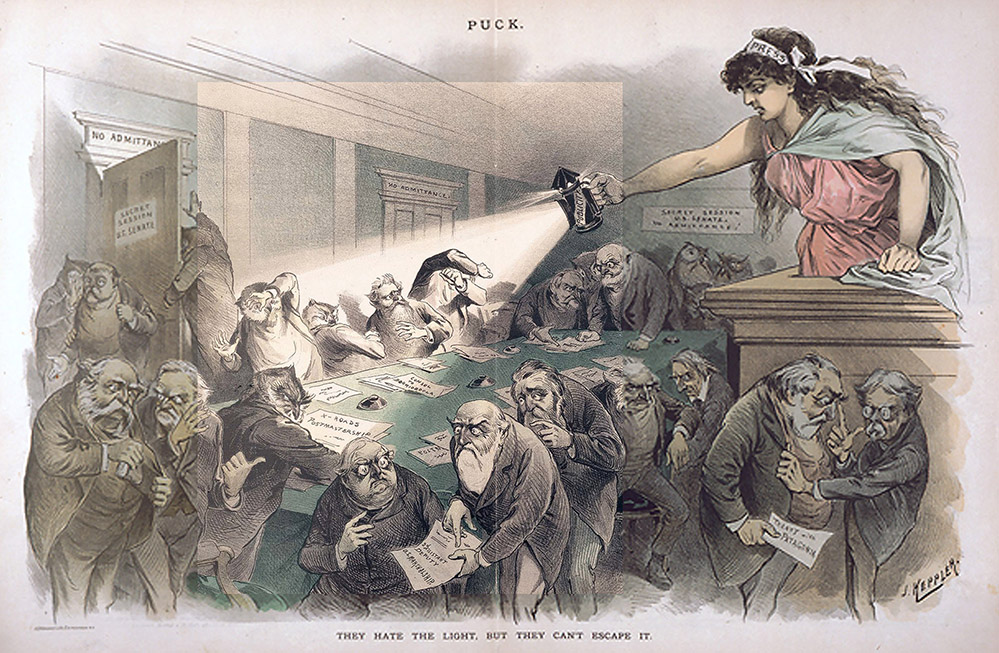

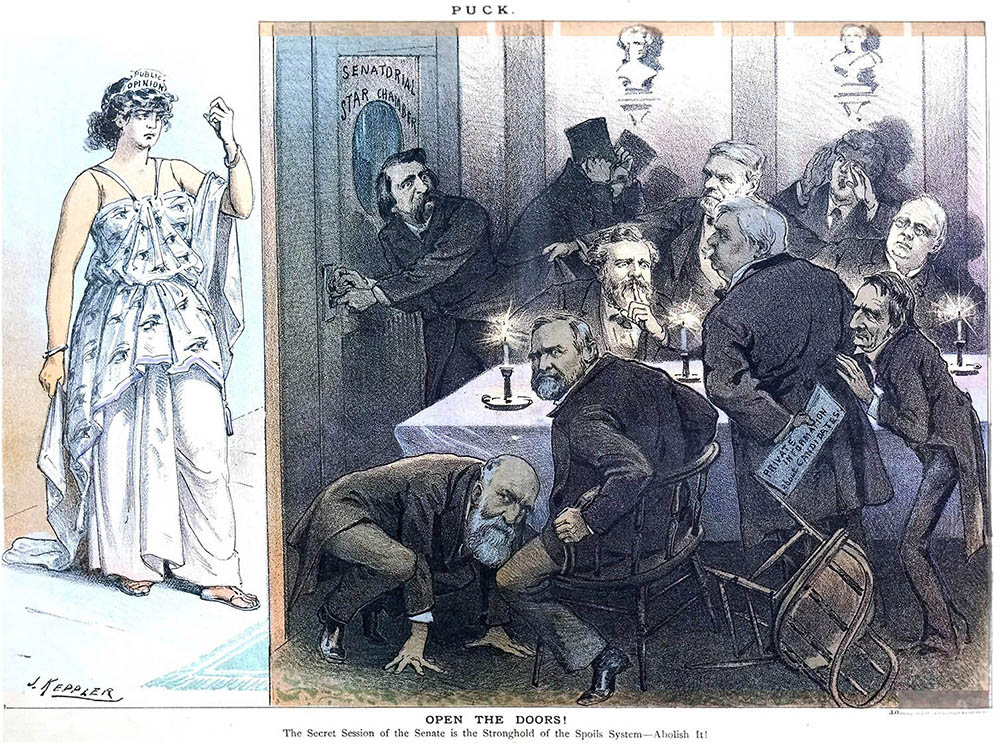

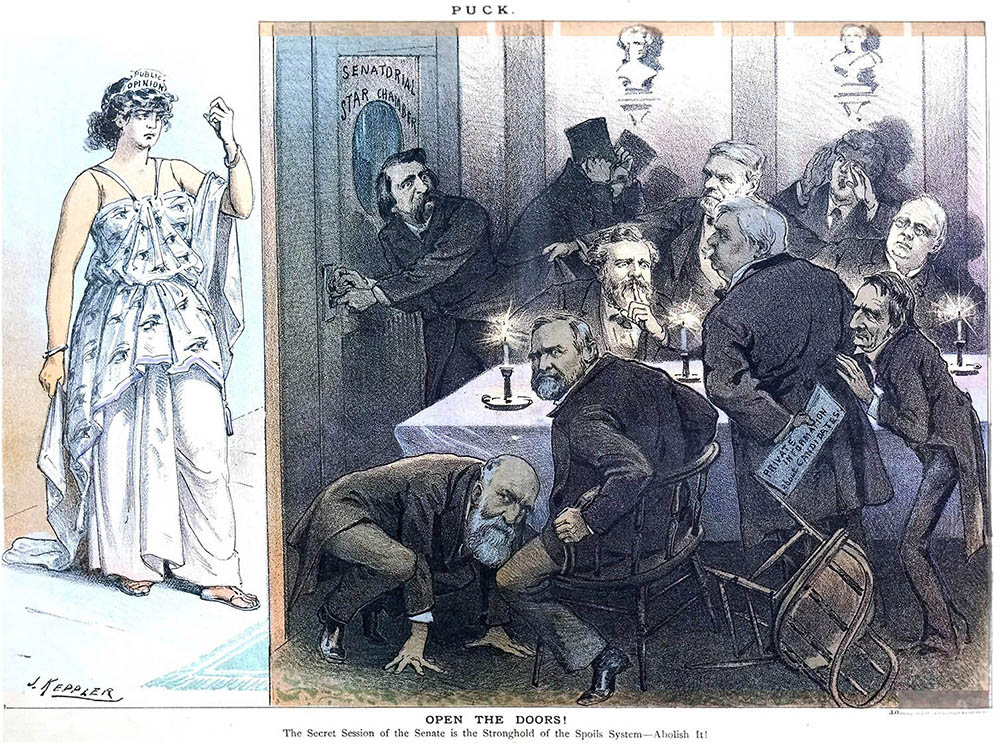

Committee rooms before and after the sunshine laws

Committee rooms before and after the sunshine laws

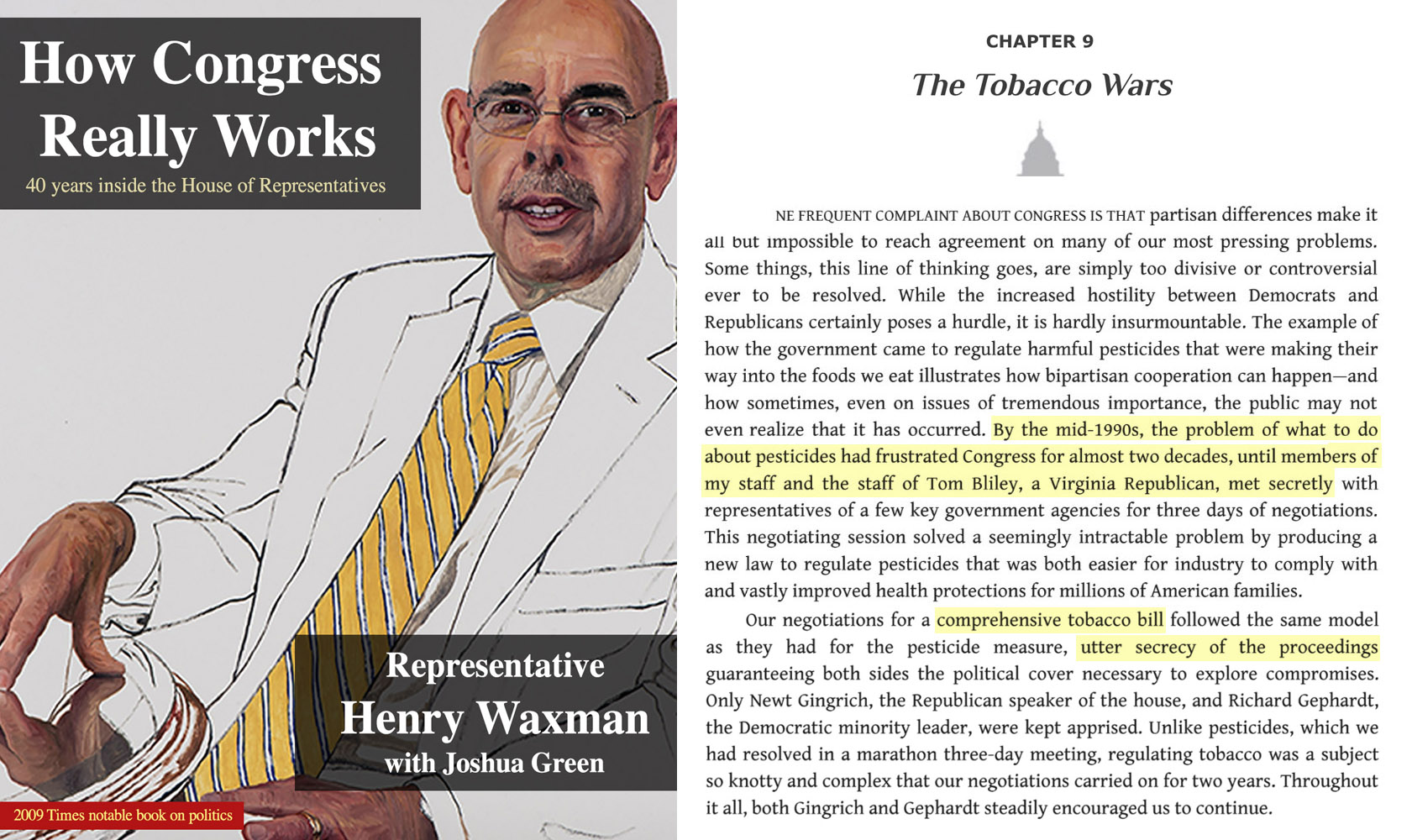

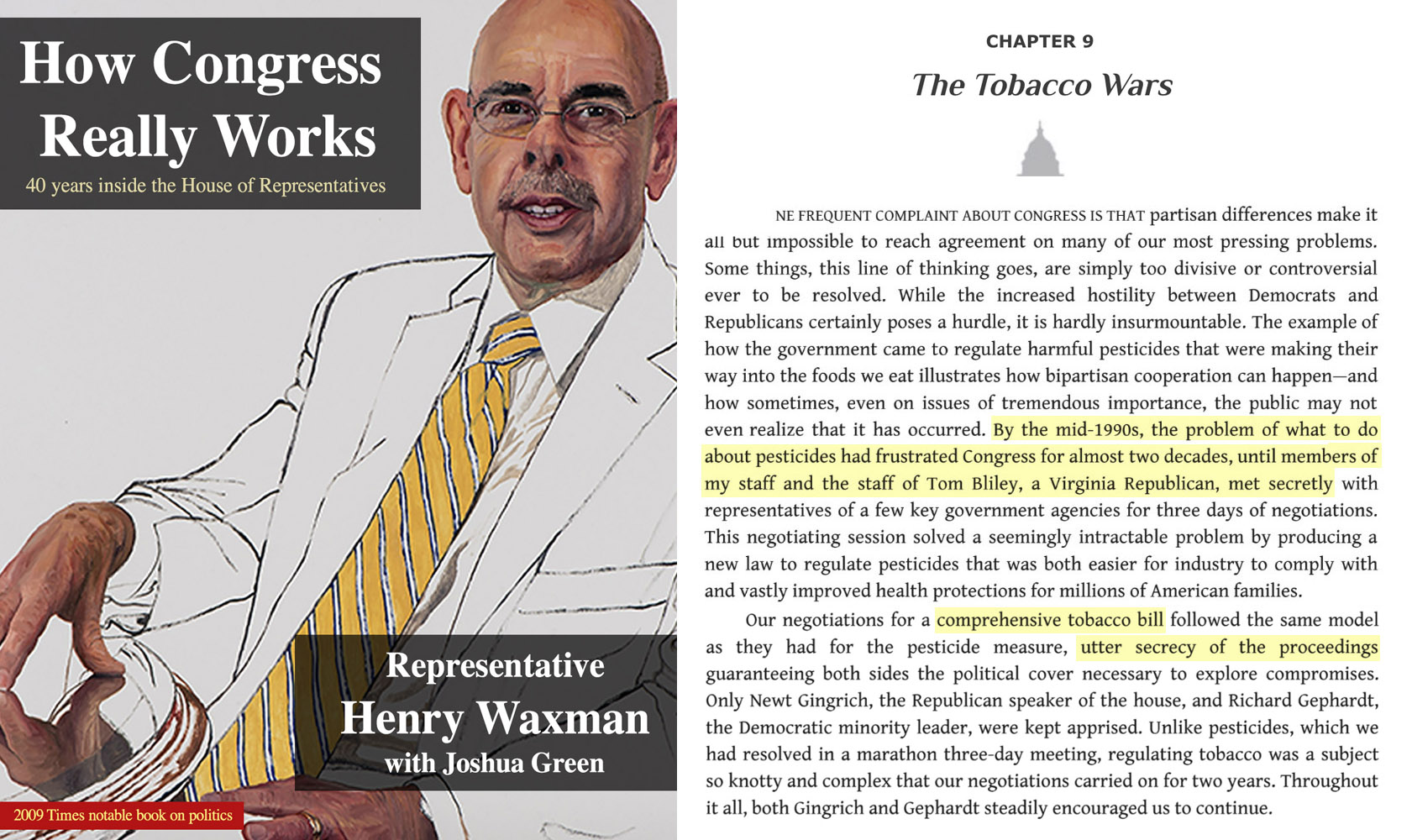

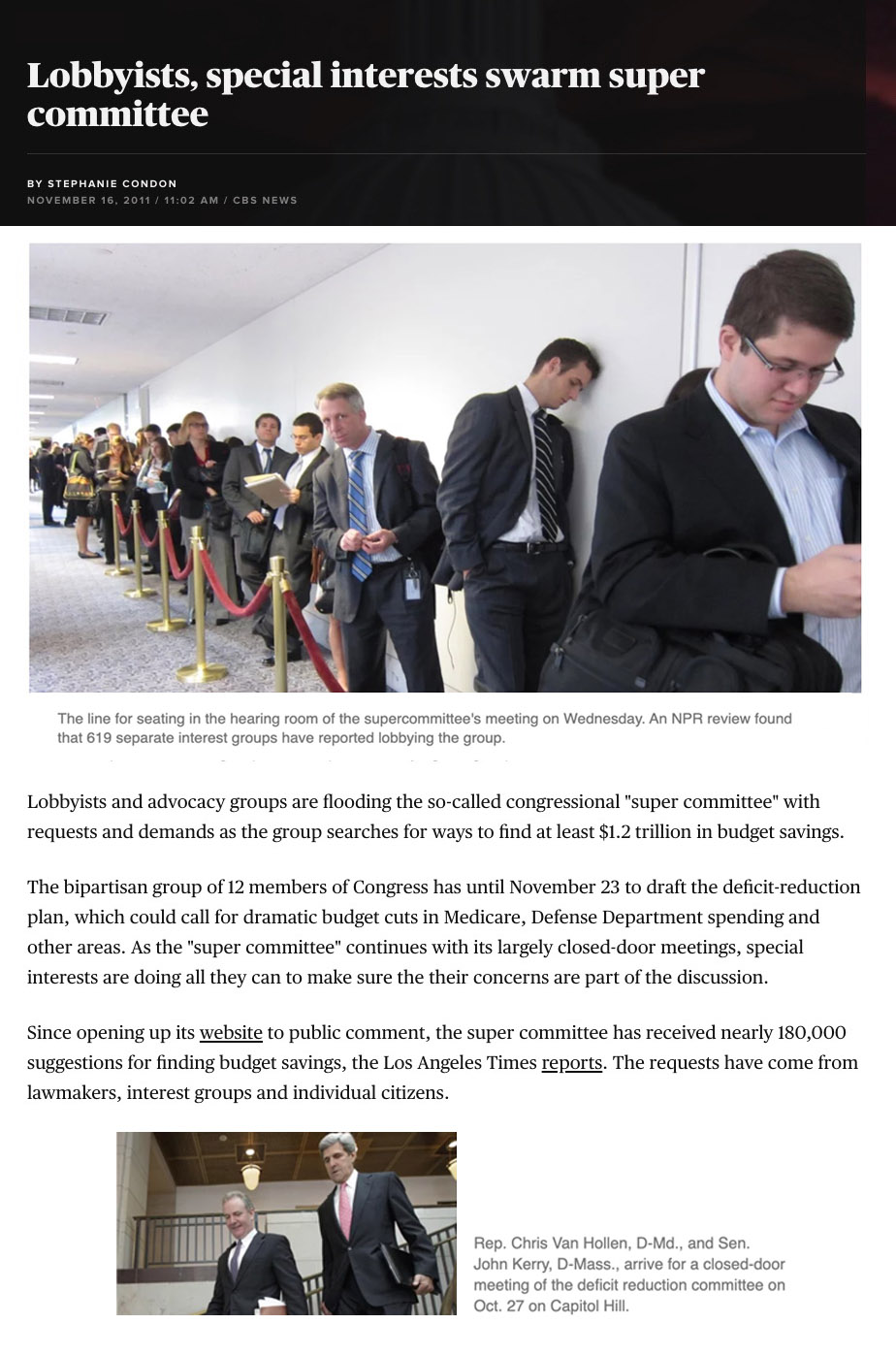

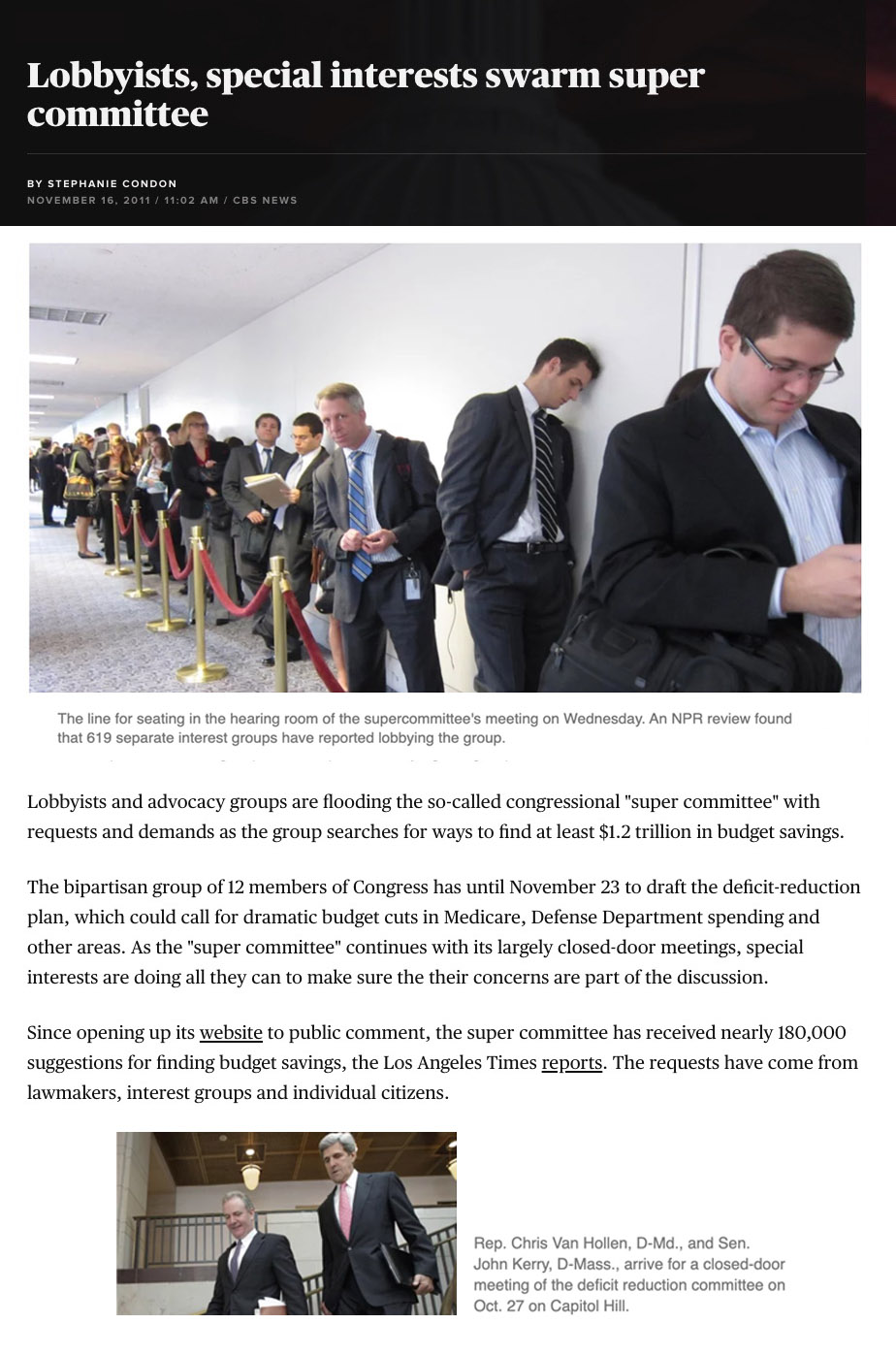

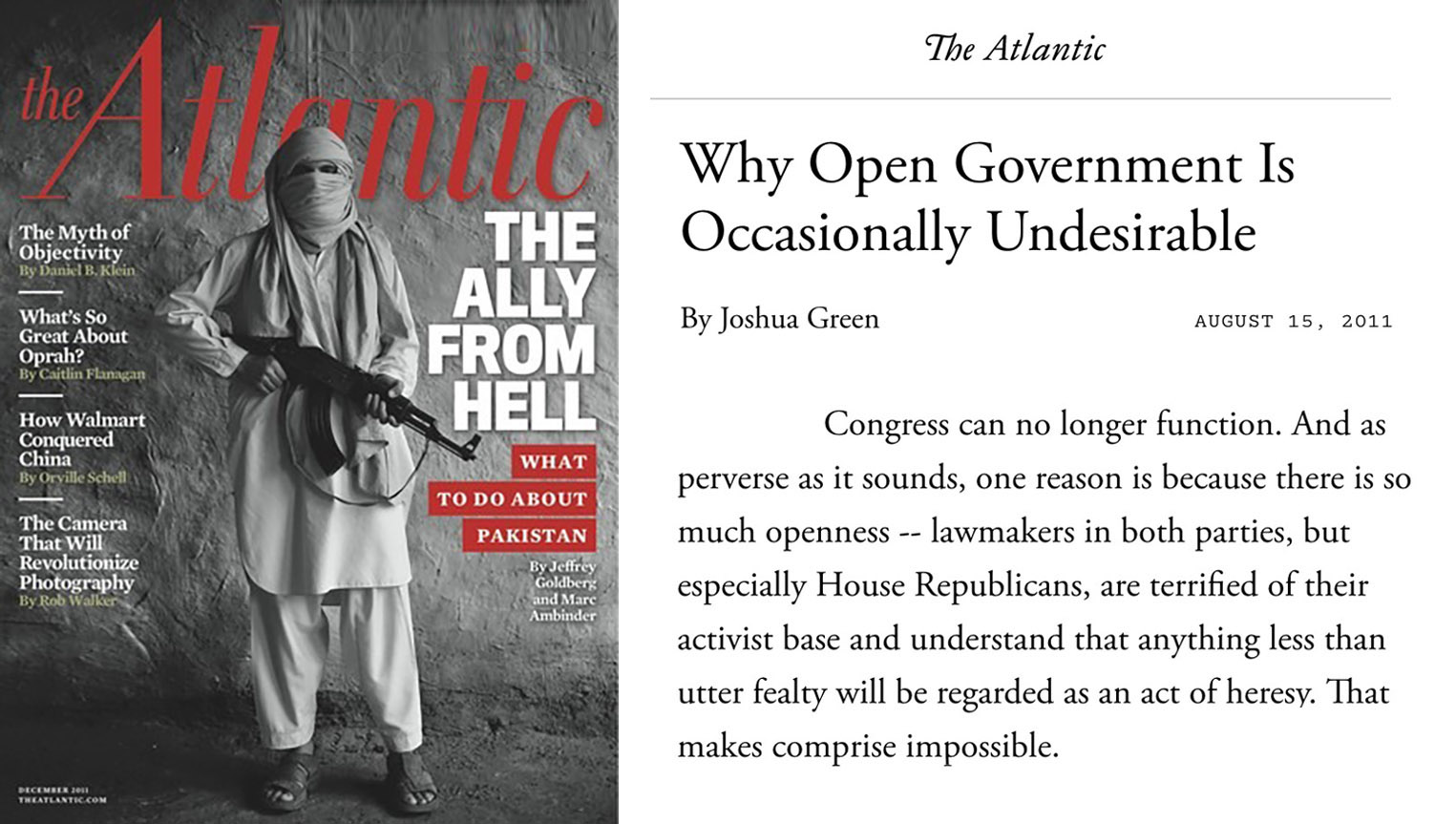

It’s the special interests that have the greatest investment in transparency, since that would allow them to pressure the negotiators and poison the political atmosphere in advance of any deal.Joshua Green 2011

Against Supercommittee Transparency

An action performed in public is more susceptible to influence by other agents than an action performed in secret is. Therefore those with the most resources at their disposal are in a better position to influence the behavior of others if such behavior takes place in the open than if it is performed in secrecy.Bernard Manin 2015

Secrecy and Publicity

The original reason for secrecy was protection against interference with Parliamentary proceedings by the Crown.Harold Cross 1953

The People’s Right to Know

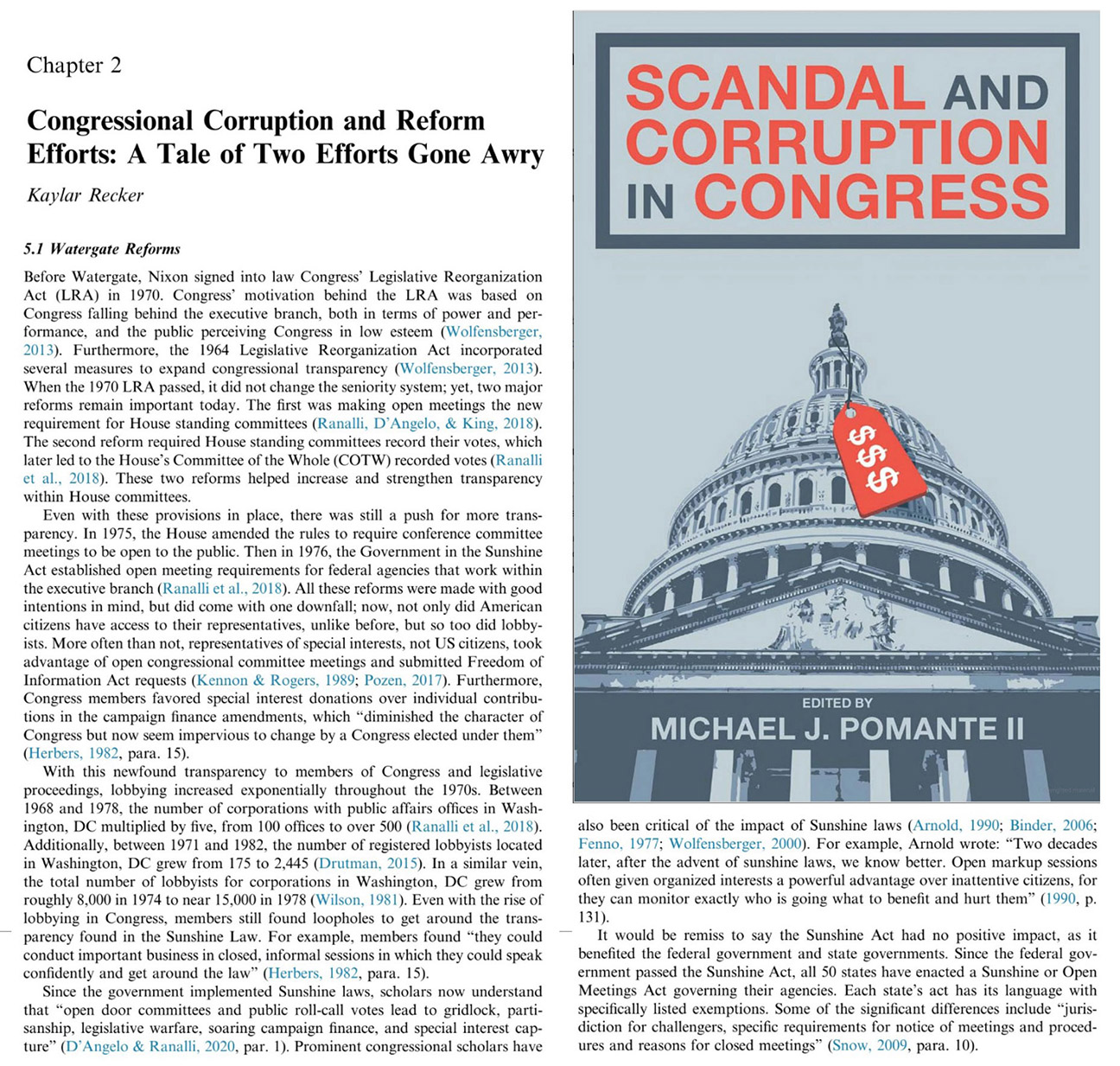

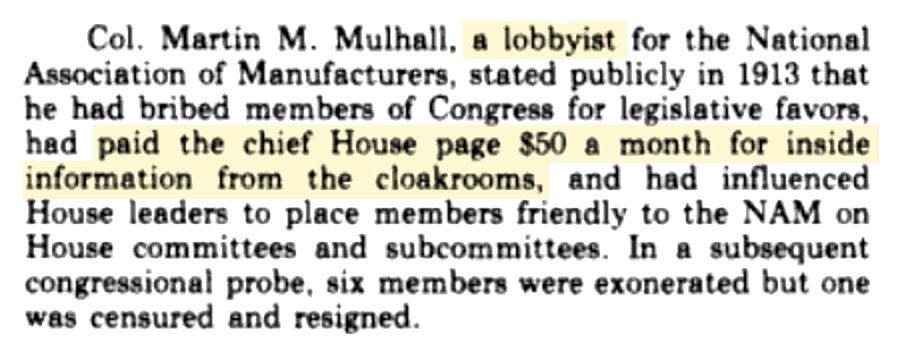

Pomante Recker 2023 – Scandal and Corruption in Congress

Pomante Recker 2023 – Scandal and Corruption in Congress

Secrecy is vital in the execution of some public policies.Karina Furtado Rodrigues

Unveiling the concept of transparency

The public enjoys no specific constitutional “right to know,” nor does Congress have an affirmative obligation either to disclose or to permit unlimited access to its materials or processes. On the contrary, materials and policy decisions that in Congress’ judgment require secrecy may be constitutionally withheld from the public.Daniel M. O’Brien 1980

The First Amendment and the Public’s Right to Know

Disclosure does not work, cannot be fixed, and can do more harm than good. It has failed time after time, in place after place in area after area, in method after method, in decade after decade.Omri Ben-Shahar & Carl E. Schneider 2014

More Than You Wanted to Know: Failure of Mandated Disclosure

Zeke Miller 2013 - The Bipartisan Call To Bring Back The Smoke-Filled Room

Zeke Miller 2013 - The Bipartisan Call To Bring Back The Smoke-Filled Room

A lot of lobbyists really complain about closed meetings.Jaqueline Calmes 1987

Congressional Quarterly – Fading Sunshine Reforms

Deals are never reached in front of the television camera.David Frum 2010

Blame yesterday's reforms for today's gridlocked Congress

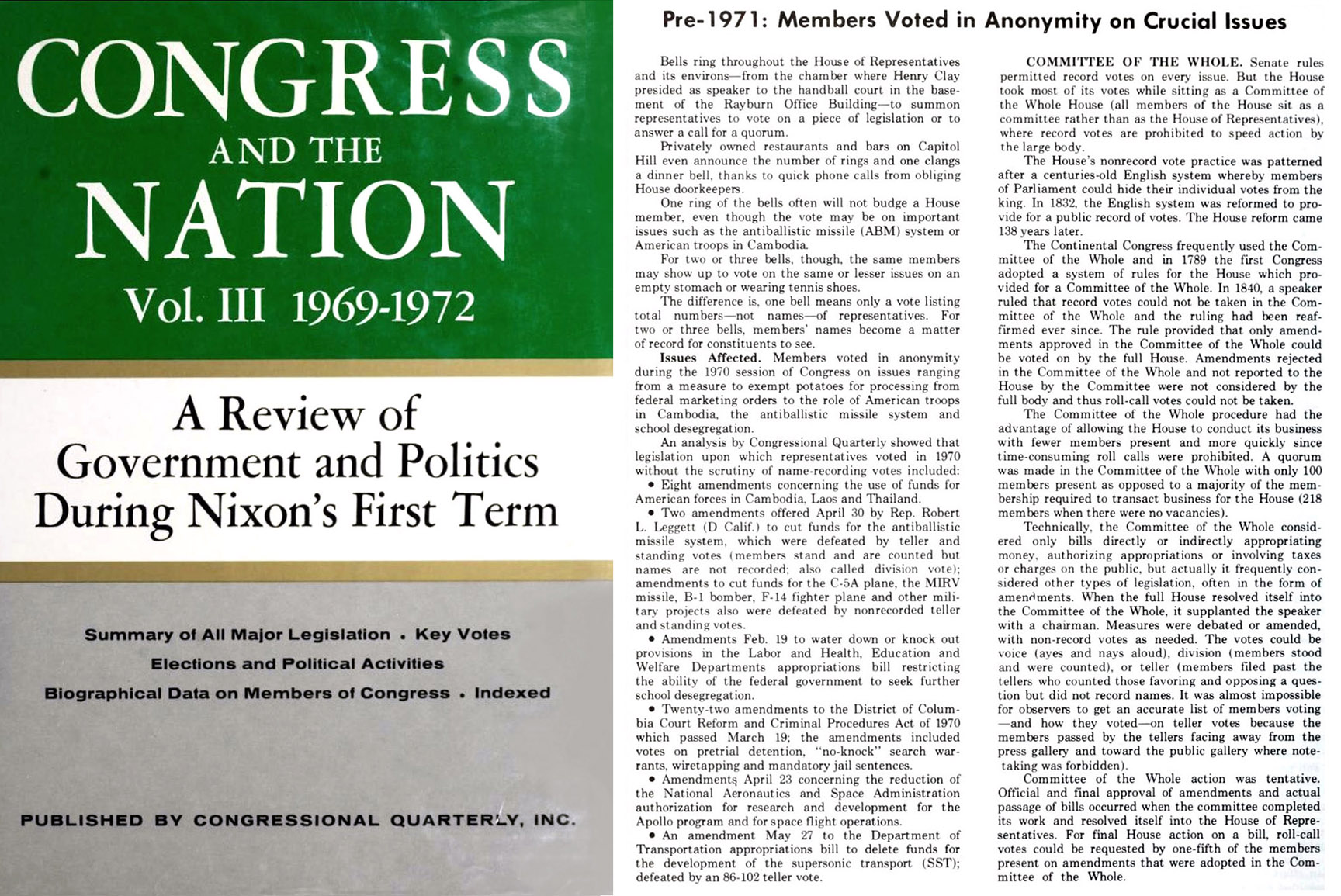

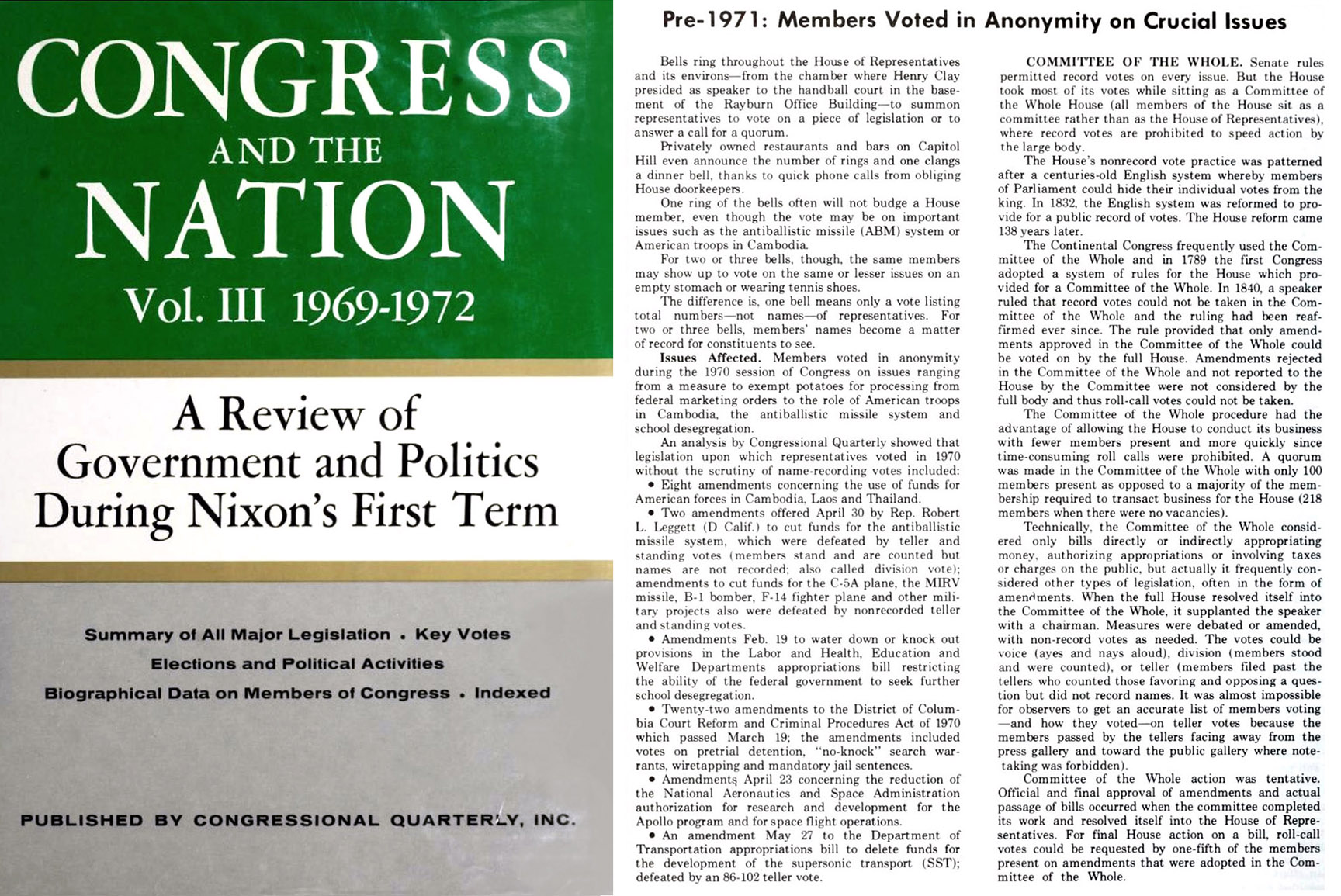

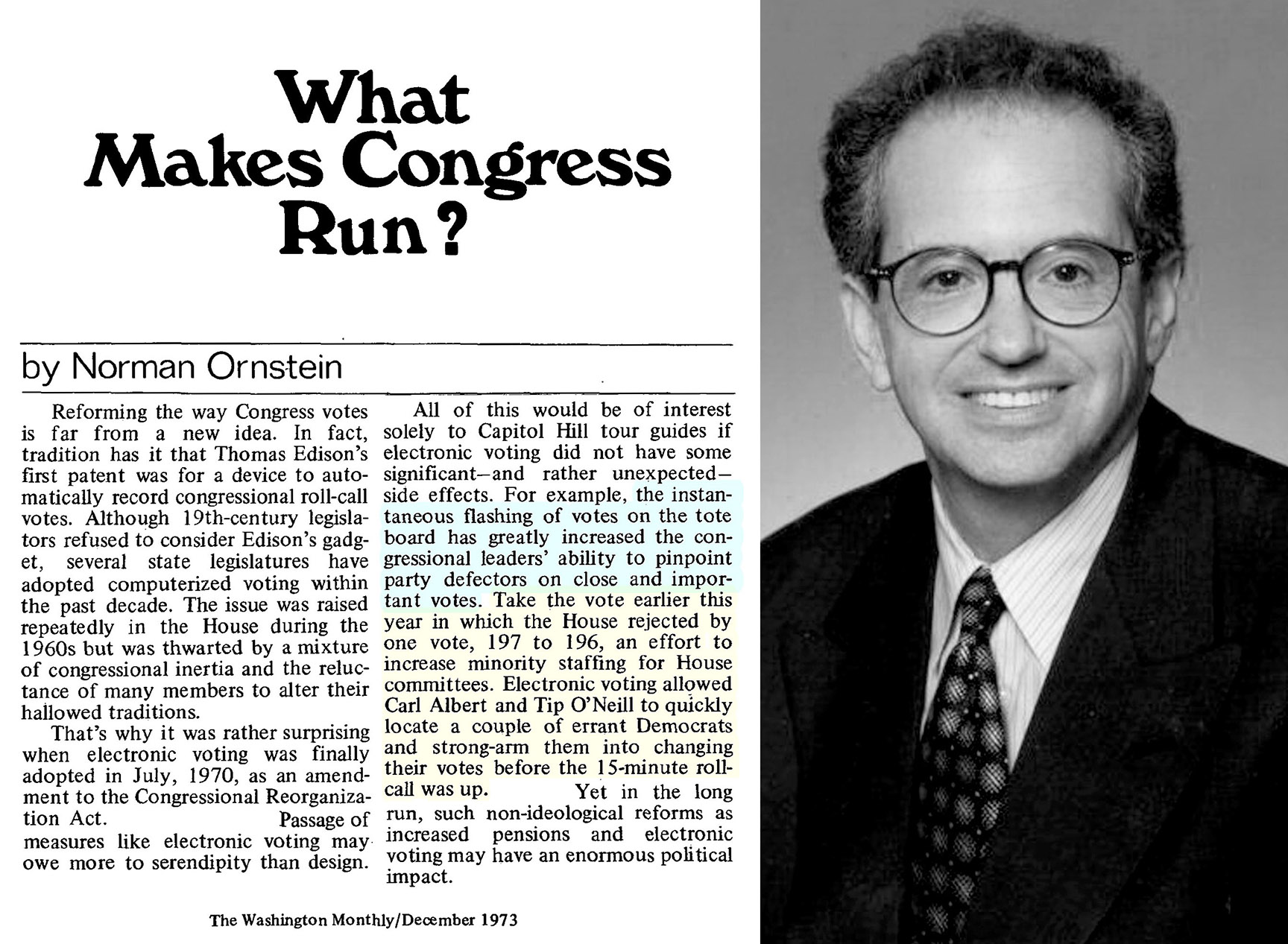

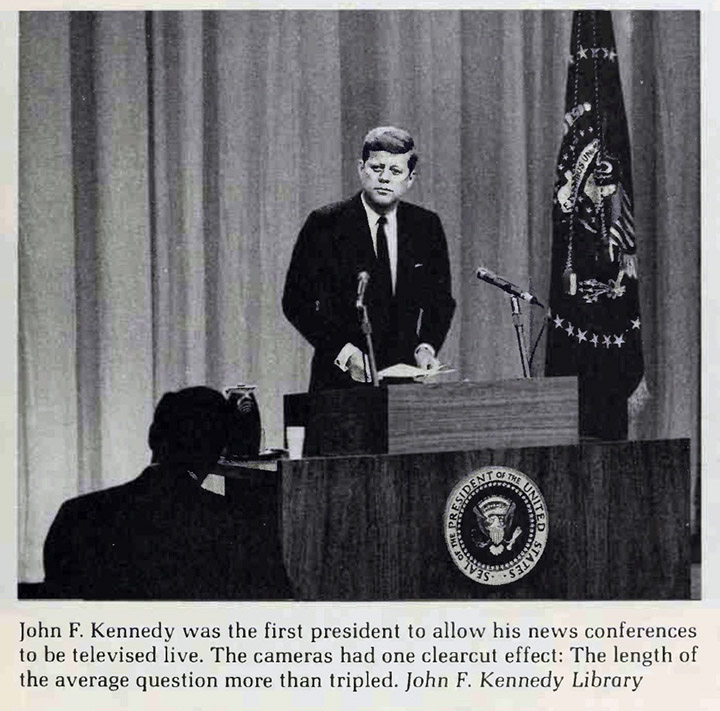

Journalists and lobbyists in the galleries were beginning to try to record the votes of individual legislators .Bibby & Davidson 1972

On Capitol HillNote: Even before the 1970s sunshine reforms, lobbyists, not the public, pushed to get the votes of legislators

Ezra Klein – 2013 Washington Post

Ezra Klein – 2013 Washington Post

The final breakthrough in the civil rights struggle occurred behind closed doors.Julian Zelizer 2015

Fierce Urgency of Now

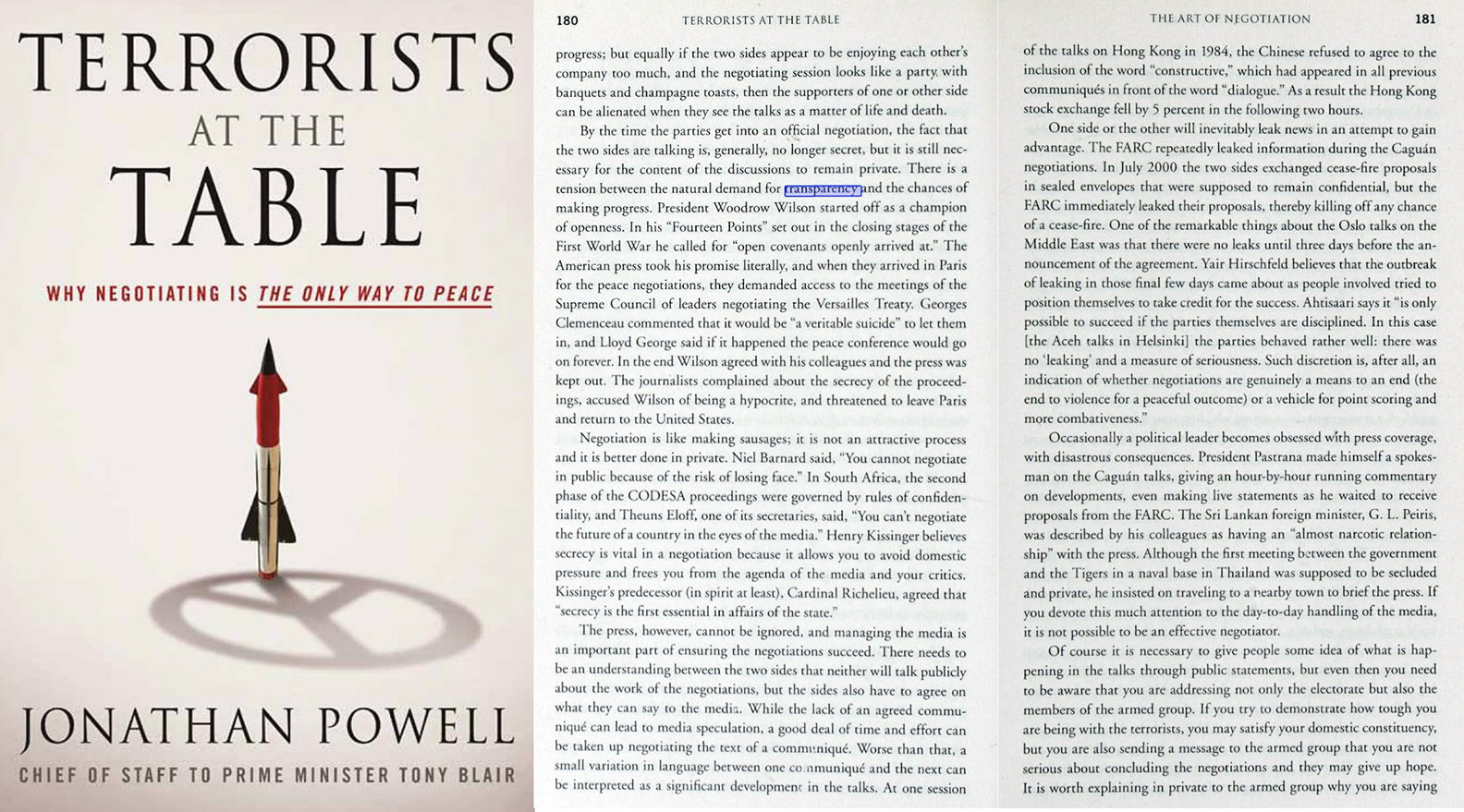

Negotiations often have to be private, and there's a place for frankness and private conversations in politics and in governing.John Wonderlich 2012 (Sunlight Foundation)

Open-Government Watchdogs OK With Closed-Door Fiscal Cliff Talks

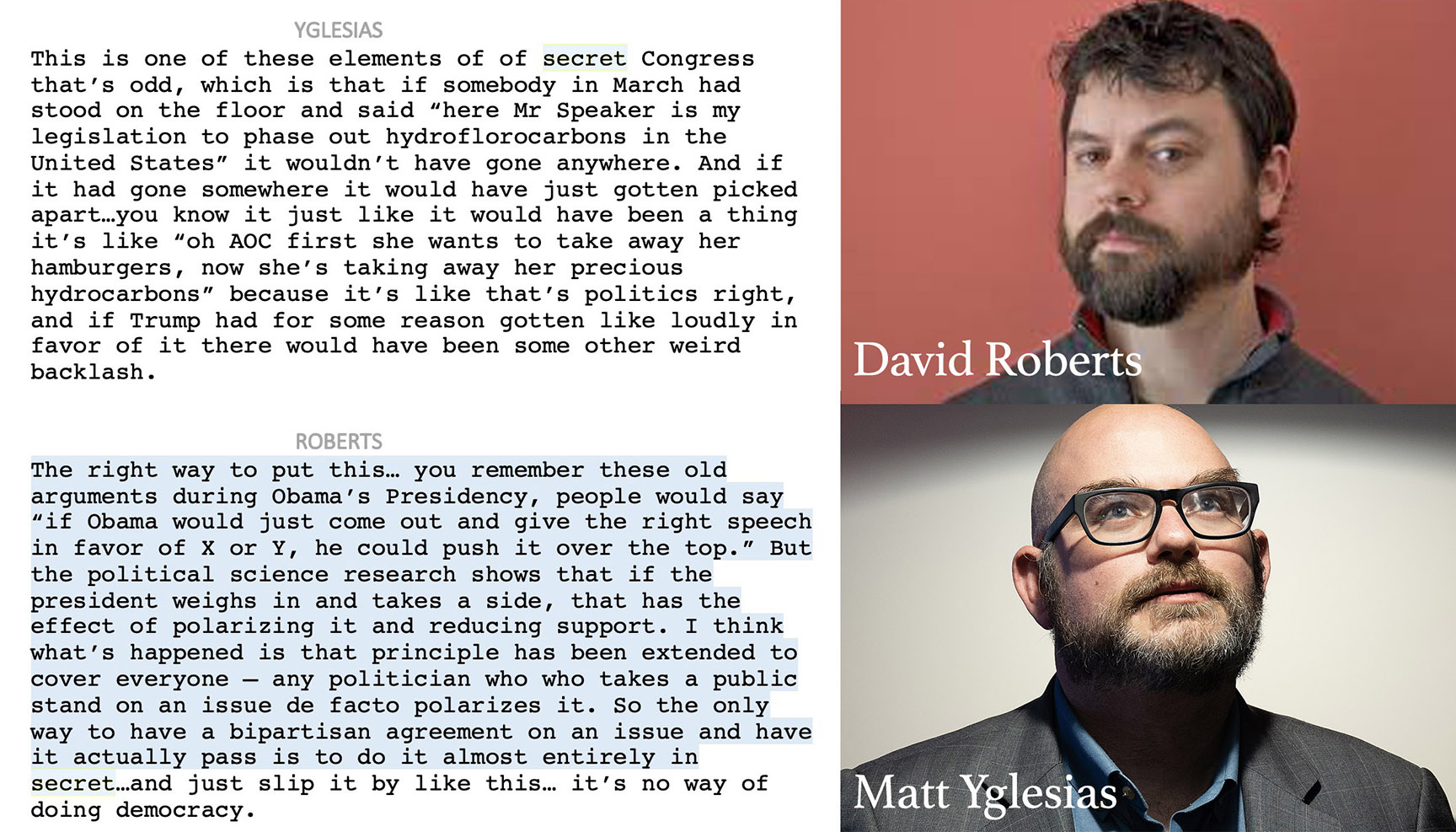

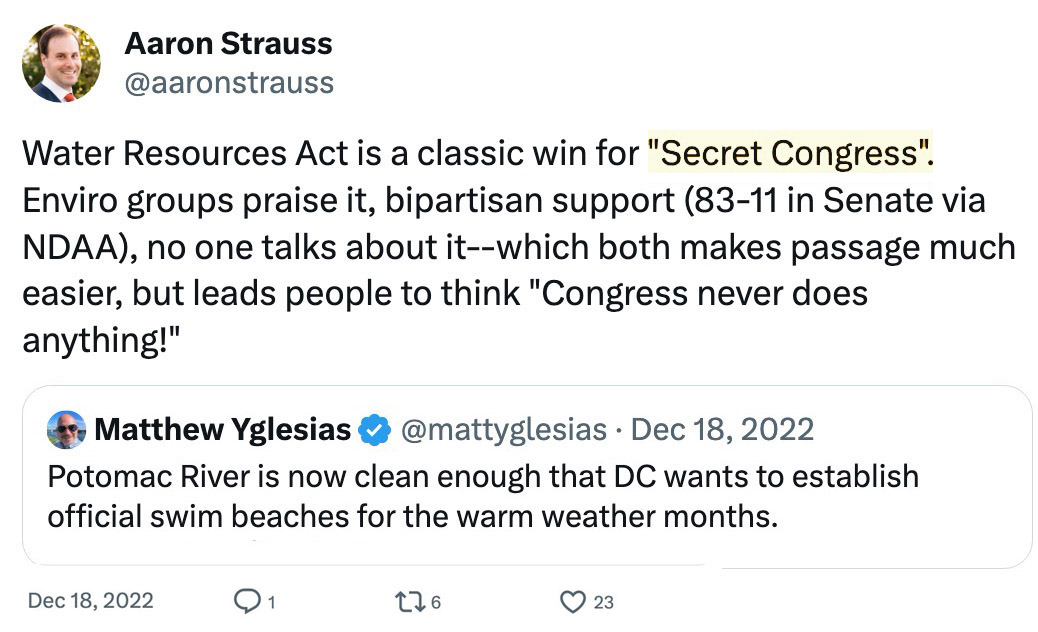

The “secret congress” theory holds that a successful compromise can happen as long as no one makes a fuss over it. Economist 2024

The "Secret Congress" Theory

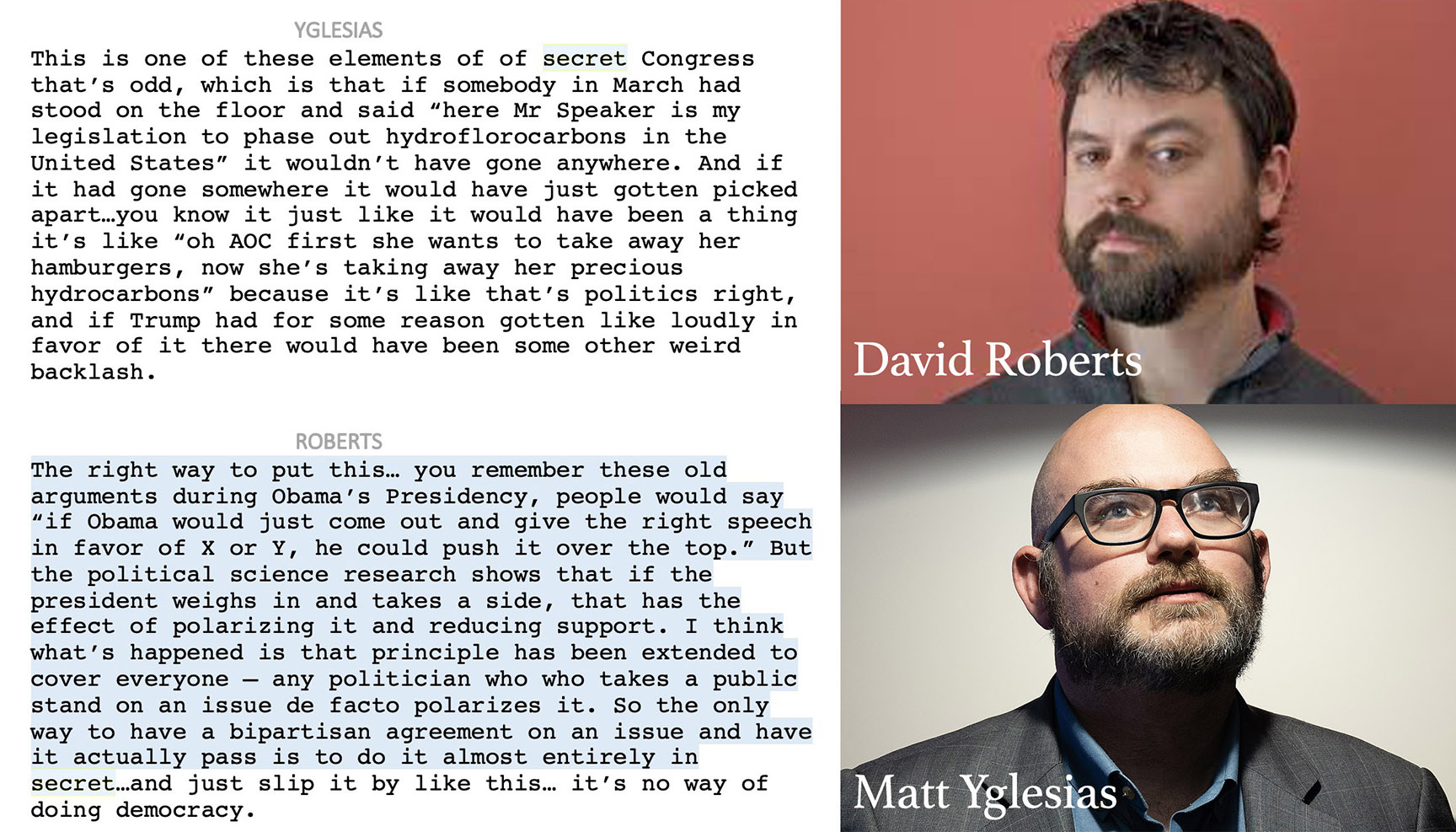

Matthew Yglesias 2024 - Transparency is Overrated

Matthew Yglesias 2024 - Transparency is Overrated

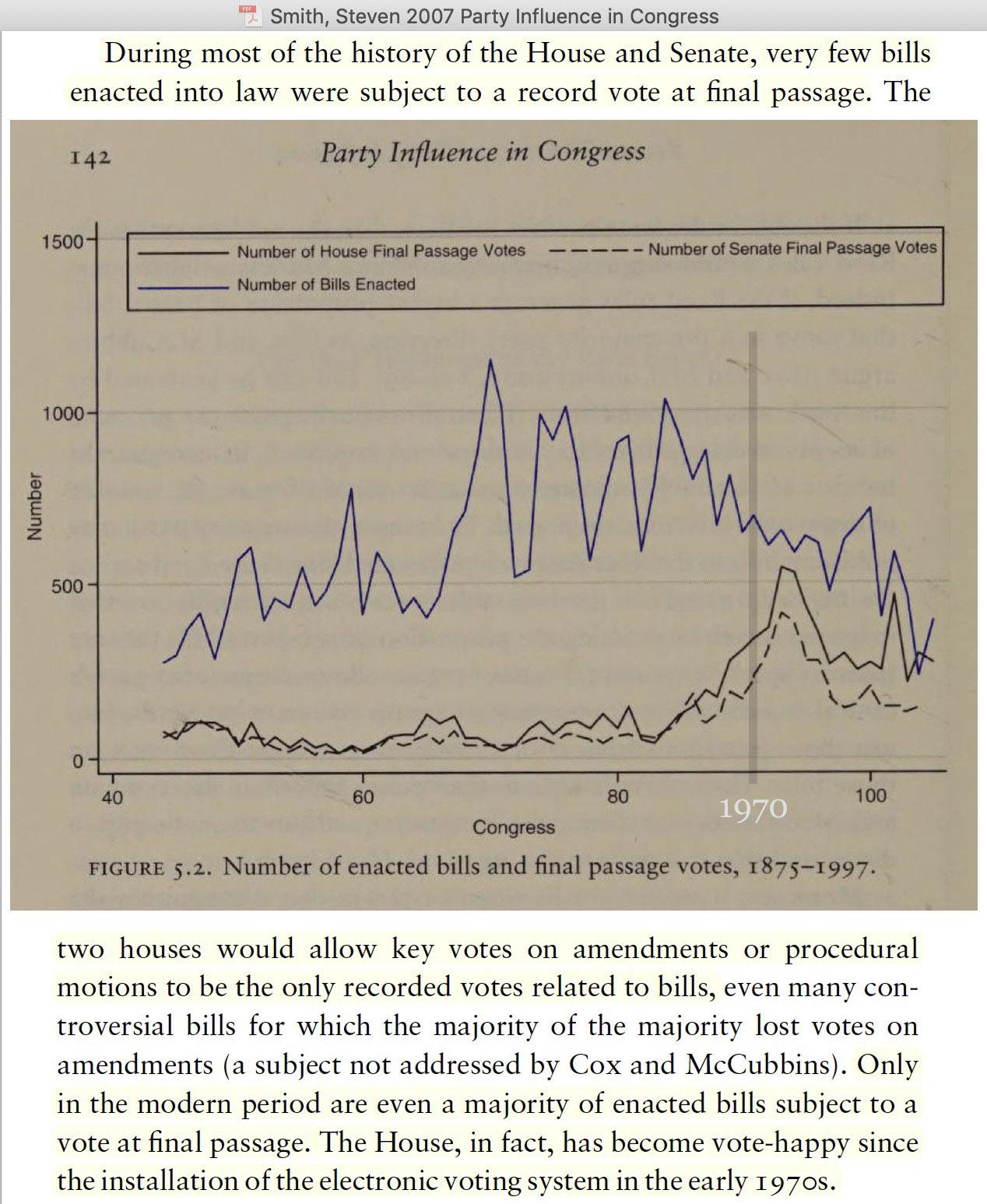

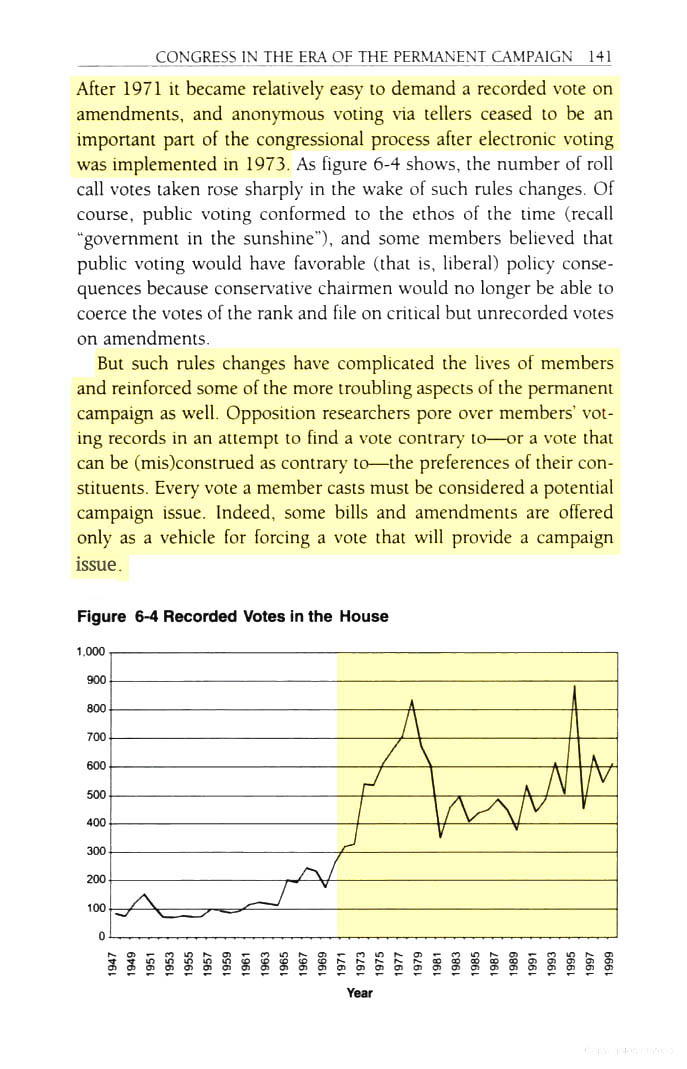

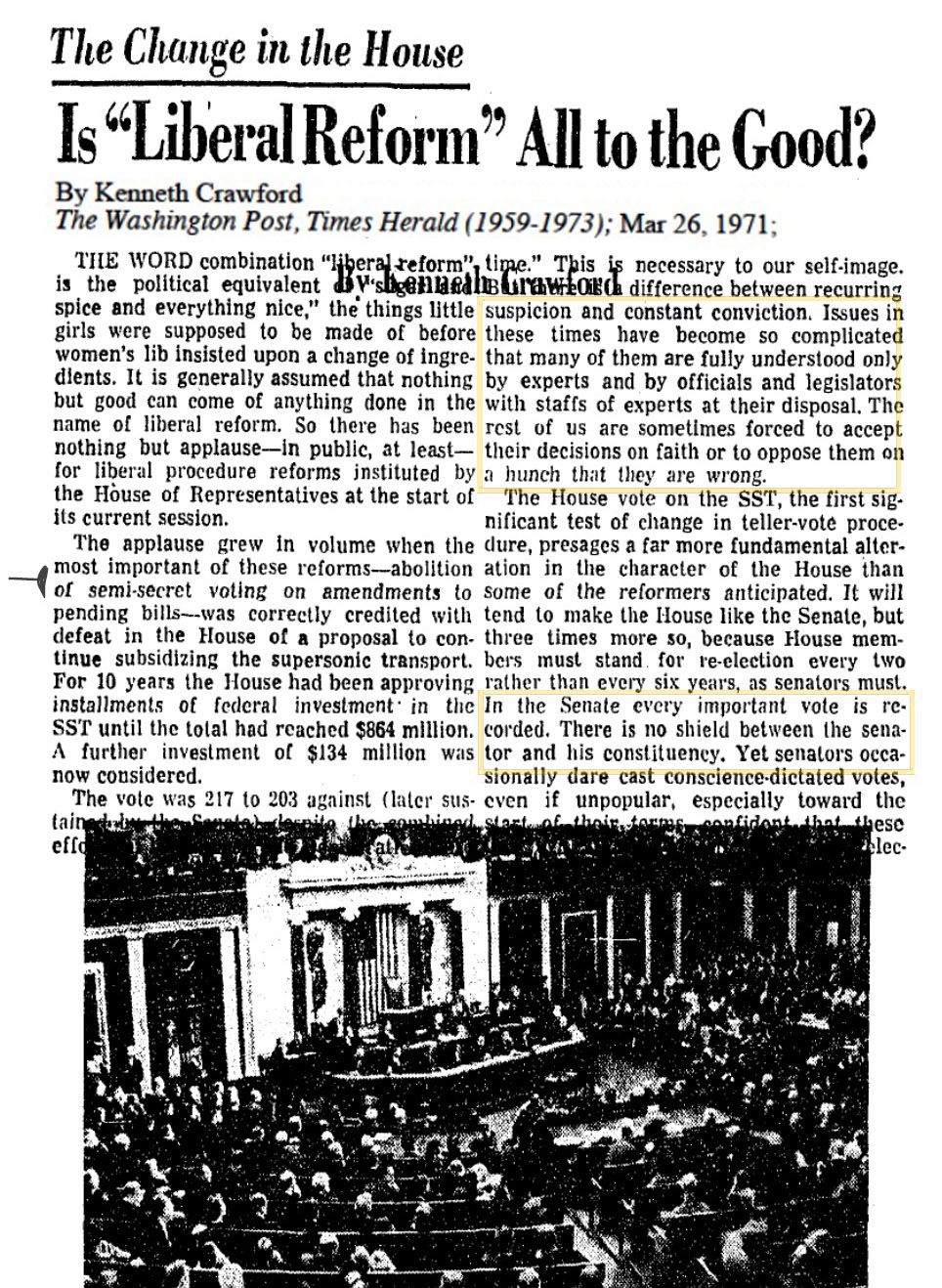

The House, heeding the demands of reformers, voted today to scrap the system under which it has shaped much of its legislation by secret vote since the first Congress in 1789.Marjorie Hunter July 28, 1970

House Backs End of Teller Votes on Amendments (New York Times)

The more Congress gives people voice, accountability, representation, and open, visible procedures, the more the people will be dissatisfied with Congress.John Hibbing 2002

How to Make Congress Popular (trust)

Then we had open mark-up sessions. And who came to open mark-up sessions? The press and the lobbyists.Timothy Kearley 1982

The American journal of tax policy

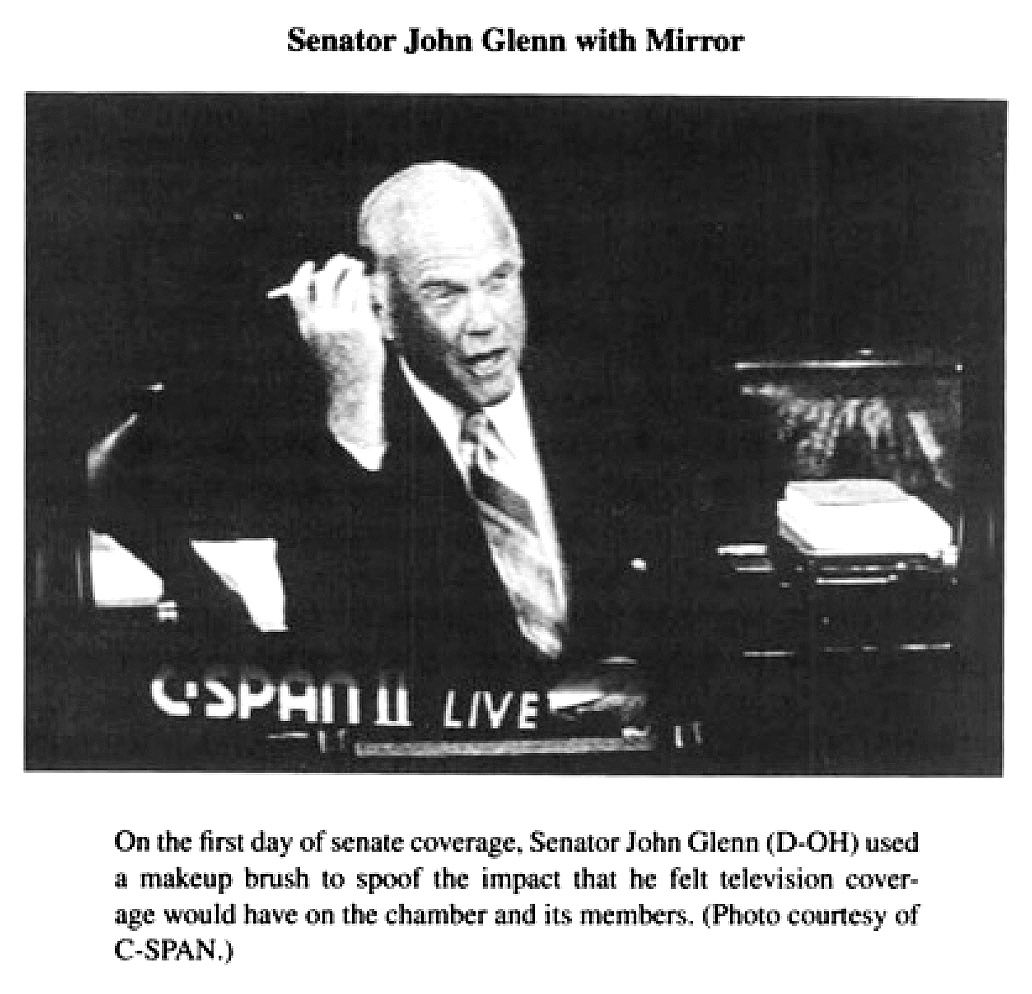

Senator Ben Sasse 2020 - Cut the Cameras

“Cut the cameras. Most of what happens in committee hearings isn’t oversight, it’s showmanship. Senators make speeches that get chopped up, shipped to home-state TV stations, and blasted across social media. They aren’t trying to learn from witnesses, uncover details, or improve legislation. They’re competing for sound bites. There’s one notable exception: The Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, the majority of whose work is done in secret. Without posturing for cameras, Republicans and Democrats cooperate on some of America’s most complicated and urgent problems. Other committees could follow their example, while keeping transparency by making transcripts and real-time”

Senator Ben Sasse 2020 - Cut the Cameras

Public engagement and transparency may contribute to inferior regulatory outcomes as well as burdensome or ineffectual regulatory processes. Jennifer Nash & Daniel Walters 2015

Public Engagement and Transparency in Regulation

Yet, where there is so much information, others might argue that transparency is reduced, a result of information overload and noise...information overload implies that corruption and transparency can coexist.Albert Breton 2007

The Economics of Transparency in Politics

I think one of the most tragic things that has happened since I have been in Washington was making all the conferences open to us lobbyists.Lobbyist Carter Manasco 1975

Congressional Hearings on Lobbying

President Joe Biden 2022 - Secret Ballot Voting in Congress

Biden announces his support of secret ballots in legislatures during his March 2022 State of the Union address. His comments come at 2:07:26 (two hours, seven minutes and 26 seconds into this stream). He says ‘I may be wrong, but my guess is, if we took a secret ballot in this floor, that we’d all agree that the present tax system ain’t fair. We have to fix it.’ It is worth noting that Biden was a member of Congress in 1986 when Congress decided to take the tax legislation behind closed doors in order to close loopholes and prevent the arm-twisting of members by powerful groups.

President Joe Biden 2022 - Secret Ballot Voting in Congress

Sometimes we don’t want to take a recorded vote when there are a lot of lobbyists out there.Anonymous Member of Ways and Means Committee 1984

The New Ways and Means

Freedom of debate is best guaranteed by secrecy.Josh Chafetz 2007

Democracy's Priveleged Few

Open meeting laws, which choke off all means of communication on the subject of political issues, pose a threat to free discussion and are contrary to basic First Amendment principles.Christopher J. Diehl 2010

Open Meetings and Closed Mouths

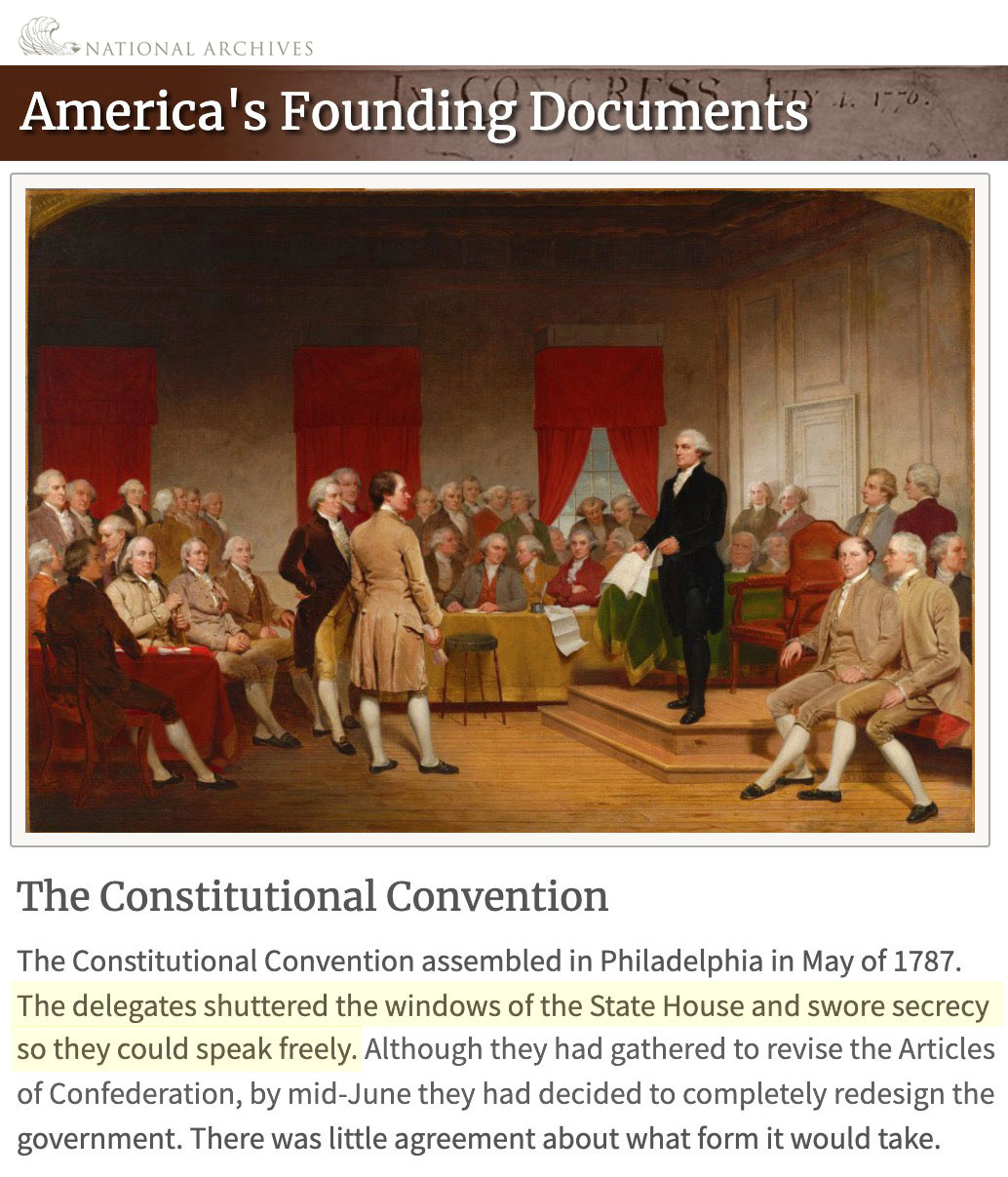

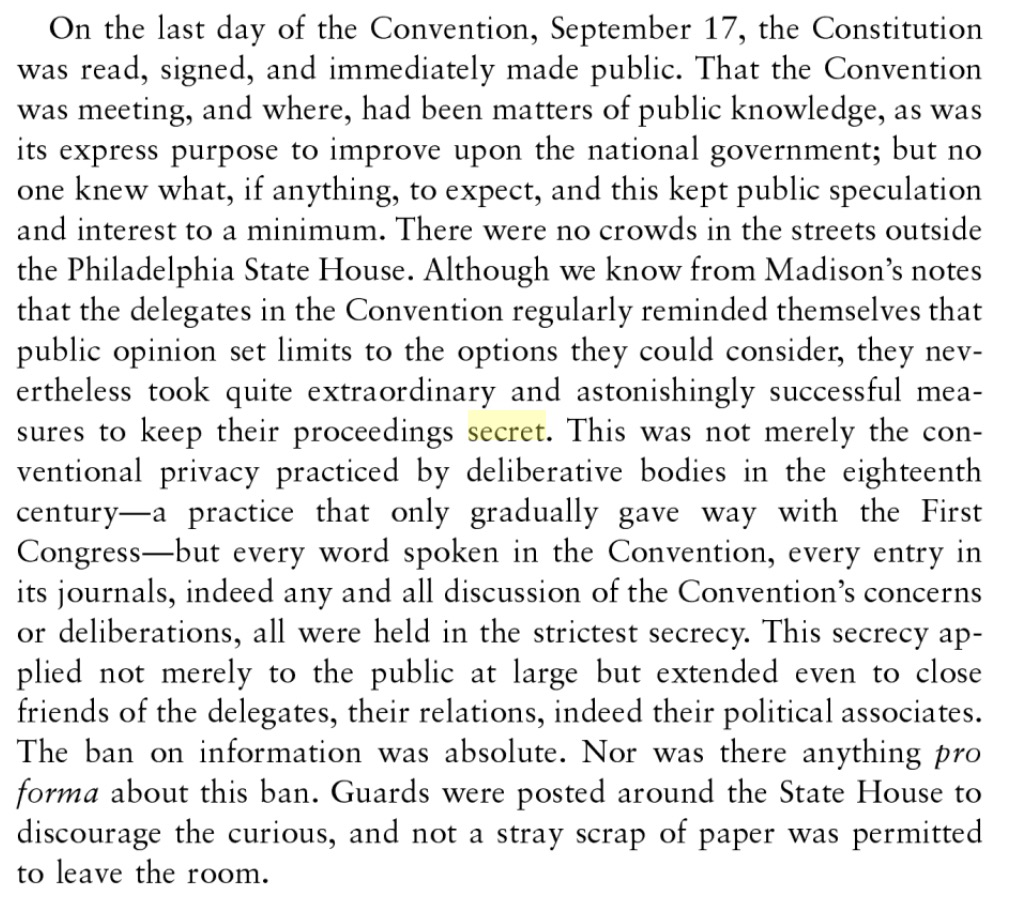

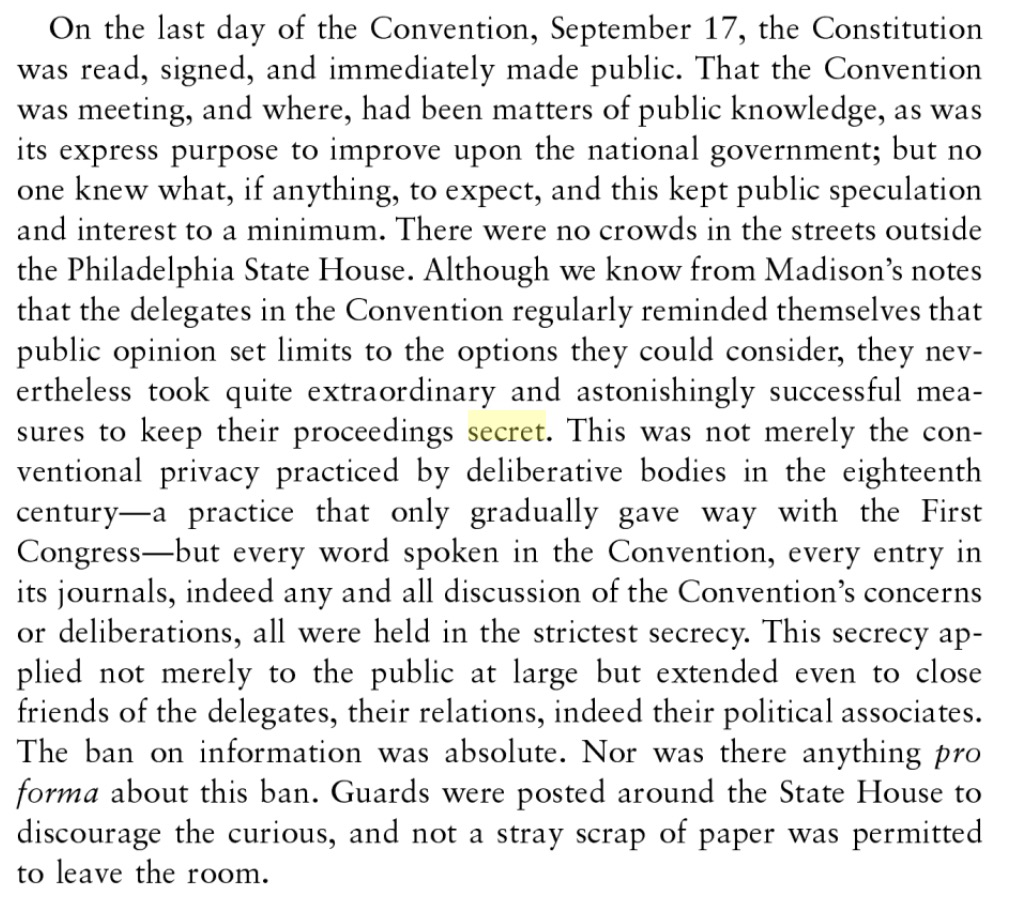

National Archives 2021 - Secrecy of Constitutional Convention

National Archives 2021 - Secrecy of Constitutional Convention

A series of three meetings was called to acquaint lobbyists with the reform bill and the proposed floor amendments. The theory was that many lobby groups would profit from open sessions and votes. Not all the groups were interested, but a few were. “We got a big lobby effort going,” Conlon said. “But it is what you would call a ʻpublic interest lobby.ʼ They understand that this bill, with our revisions, is really going to revolutionize this place.” Actually, most of the help came from such liberal and labor organizations as the AFL-CIO , the National Education Association (NEA), Americans for Democratic Action, the National Committee for an Effective Congress, the National Farmers Union , and the Anti-Defamation League of Bʼnai Bʼrith. On July 10 AFL-CIO Legislative Director (and former representative) Andrew J. Biemiller wrote a letter to legislators saying that “the AFL-CIO urges you to be present on the floor when H.R. 17654 is before the House...” Letters on behalf of the antisecrecy provisions also went out from the National Farmers Union and the NEA.Bibby & Davidson 1972

On Capitol HillNote: It is hard to imagine a bigger smoking gun than this. They knew special interests would benefit from transparency and it was easy to convince the lobbyists and interest groups of this, as they readily hopped on board. Trouble was, their ties were only on the left. They failed to see - in this highly liberal environment - that special interests on the right would benefit just as readily. This is the beginning of capture, and it was well understood that this would be the result.

Permitting open or easy access to legislators’ internal memoranda, legislative correspondence, recollections of caucus deliberations, and the like could quickly become a goldmine for disgruntled lobbyists and interest groups, as well as for political opponents.Steven F. Huefner 2003

The Neglected Value of the Legislative Privilege in State Legislatures

At first, lobbyists had no work to do on the legislation, since it was crafted by a task force in closed-door meetings… But they sprung into action after the proposal was released.Tory Newmyer 2005

Health Care Reform, 1994

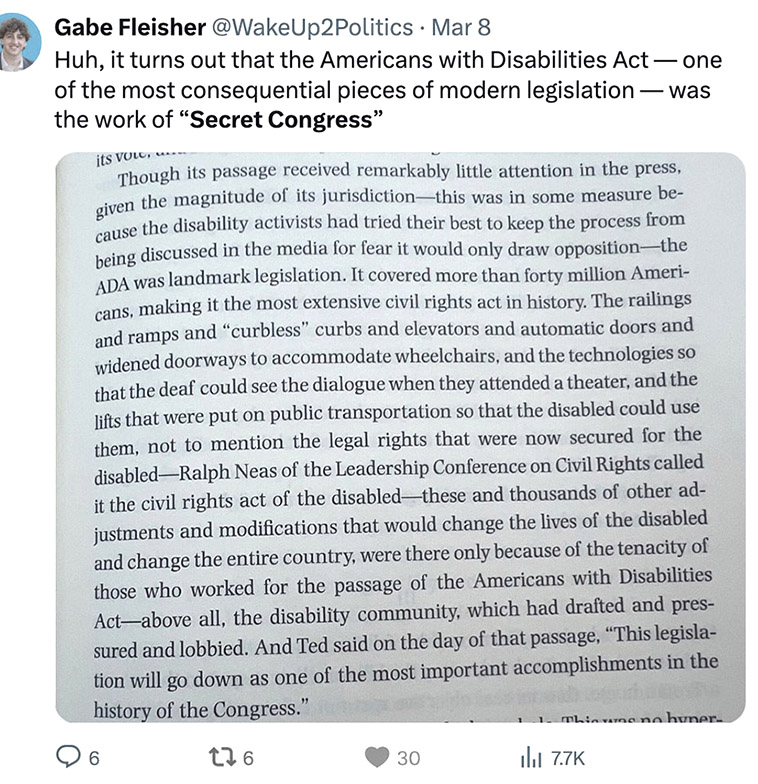

Manchin never heard from lobbies or [foreign] governments about the controversial part of the law because his team drafted it in secret. No one, save for senior Democrats in the Senate, knew they were drafting the measure. Once it came to light, and proved the saving grace for President Joe Biden’s climate agenda, the legislative process moved so quickly that no one had time to react.Alexander Ward and Susanne Lynch 2023

Manchin faces Europe’s wrath (Environment)

Frontline 2020 - Intimidation of Federal Witnesses

PBS Frontline report suggests that Amazon intimidates potential witnesses in public antitrust hearings. Confirmed witnesses are terrified of speaking publicly. At the same time Amazon is one of the nation’s biggest lobbyists, and through Jeff Bezos’ purchase of the Washington Post, also one of the biggest proponents of transparency. Immediately after purchsing the paper, they added the ubiquitous tagline “Democracy Dies in the Darkness.”

Frontline 2020 - Intimidation of Federal Witnesses

Transparency imposes a temporality on political communication that makes slow, long-term planning impossible.Byung-Chul Han 2012

The Transparency Society

Lobbyists may see how a targeted congressman really votes, prompting the member to justify his or her vote out loud and at length… ‘Legislating can be kind of difficult’ says Chairman Dan Rostenkowski. And as every Hill person knows, it gets no easier with reporters and lobbyists watching.Ronald Elving 1993

Shade Settles Over Sunshine Ideals

While the people are entitled to the fullest disclosure possible, this right, like freedom of speech or press, is not absolute or without limitations. Disclosure must always be consistent with the national security and the public interest.US Attorney General William P. Rogers 1958

The Papers of the Executive Branch

Yuval Levin 2020 - Transparency is Killing Congress

The committee system is where televised transparency has done real damage. The floors of the House and Senate have never really been great venues for deliberation. But committee work frequently did involve real negotiation and bargaining. It is where the legislature’s hardest work is done. Those few committees that function behind closed doors help prove the point. Many members of the Senate Intelligence Committee, for instance, describe their work on that committee as their favorite part of their job, and the reasons they offer fall into a clear pattern. Members of both parties can talk to one another, learn together, find shared priorities, and reach agreements. In the absence of the pressure to act out stylized cultural combat, they find real pleasure in doing the work of legislators. But in most other committees, too many hearings now basically consist of a bunch of individuals producing YouTube clips to use at election time.

Yuval Levin 2020 - Transparency is Killing Congress

The fact that committee meetings are now held in the open – a reform that was adopted in the mid-seventies – has strengthened the lobbyists’ hand and reduced the legislators’ ability to legislate.Elizabeth Drew 1983

Politics and money: the new road to corruption

The powerless will always be prevailed upon by the powerful; only secrecy can protect them from bribery and bullying.Jill Lepore 2008

Rock, Paper, Scissors

I have shown that legislators often vote one way when their actions are hidden and another way when the same actions are recorded for posterity.Douglas Arnold 2002 (Princeton)

The Press and Political Accountability

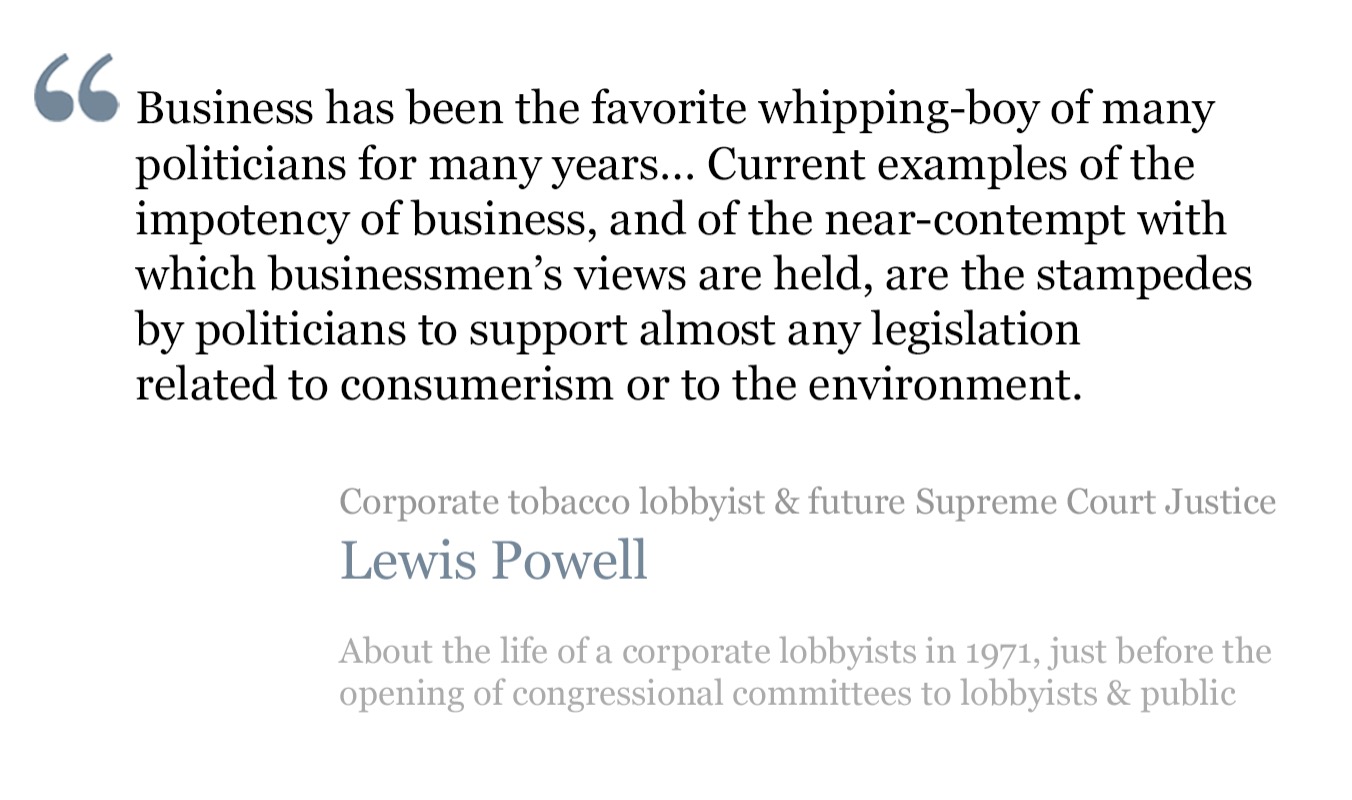

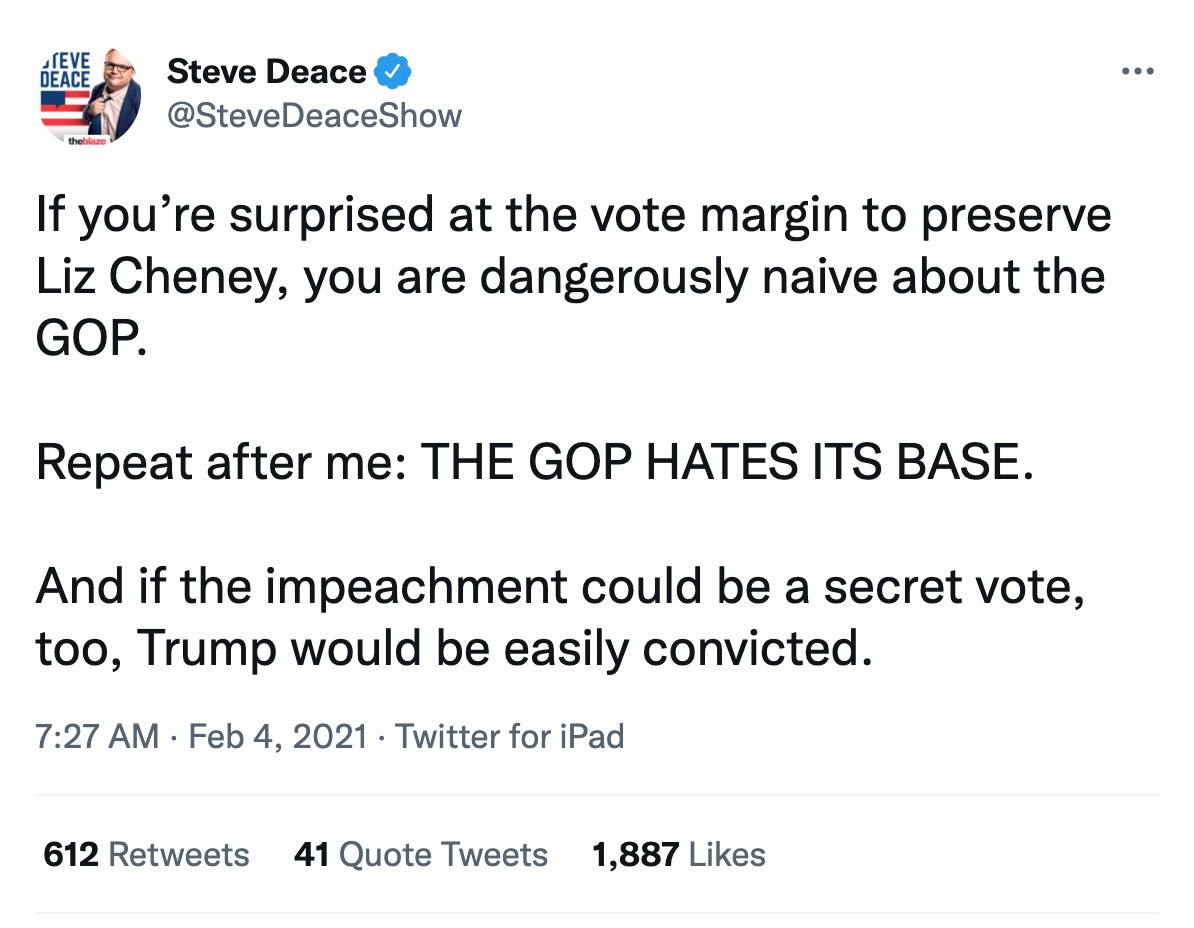

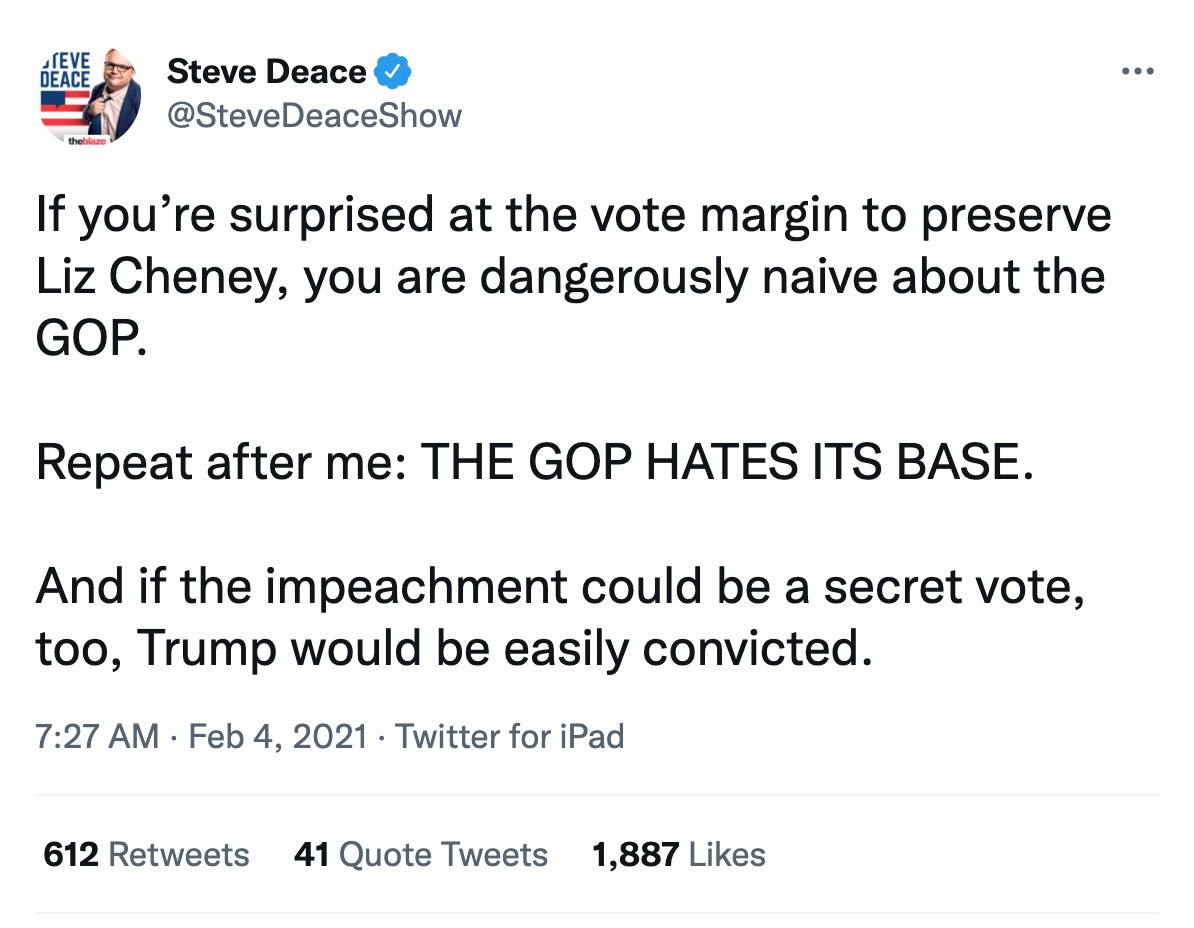

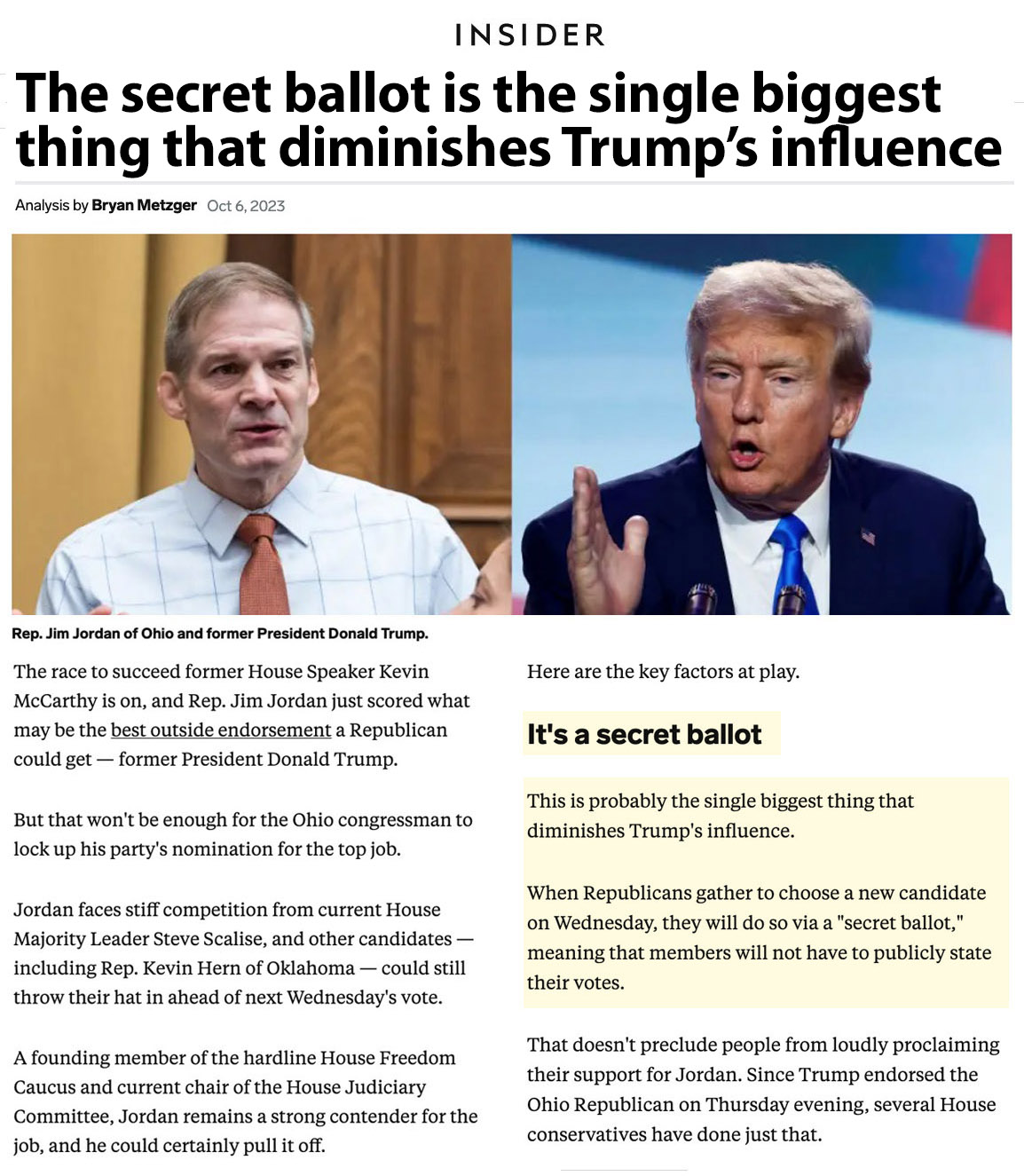

Despite attacks on President Trump, Liz Cheney retains GOP leadership role only via secret ballot of Republicans - 2021

Despite attacks on President Trump, Liz Cheney retains GOP leadership role only via secret ballot of Republicans - 2021

Ten years ago [before the majority of the sunshine laws were enacted], I could sit in a closed committee meeting and say that I couldn’t go along with something, but if they’d let me demagogue it for a while, I wouldn’t stand in the way.Joe Biden 1982

New York Times - Lexicon

There never was any legislative assembly without a discretionary power of concealing important transactions, the publication of which might be detrimental to the community.James Madison 1787

Debates in Convention

The idea was to make the process more ‘democratic’, but in practice sunshine measures intensified the access of lobbyists.James L. Payne 1991

Culture of Spending

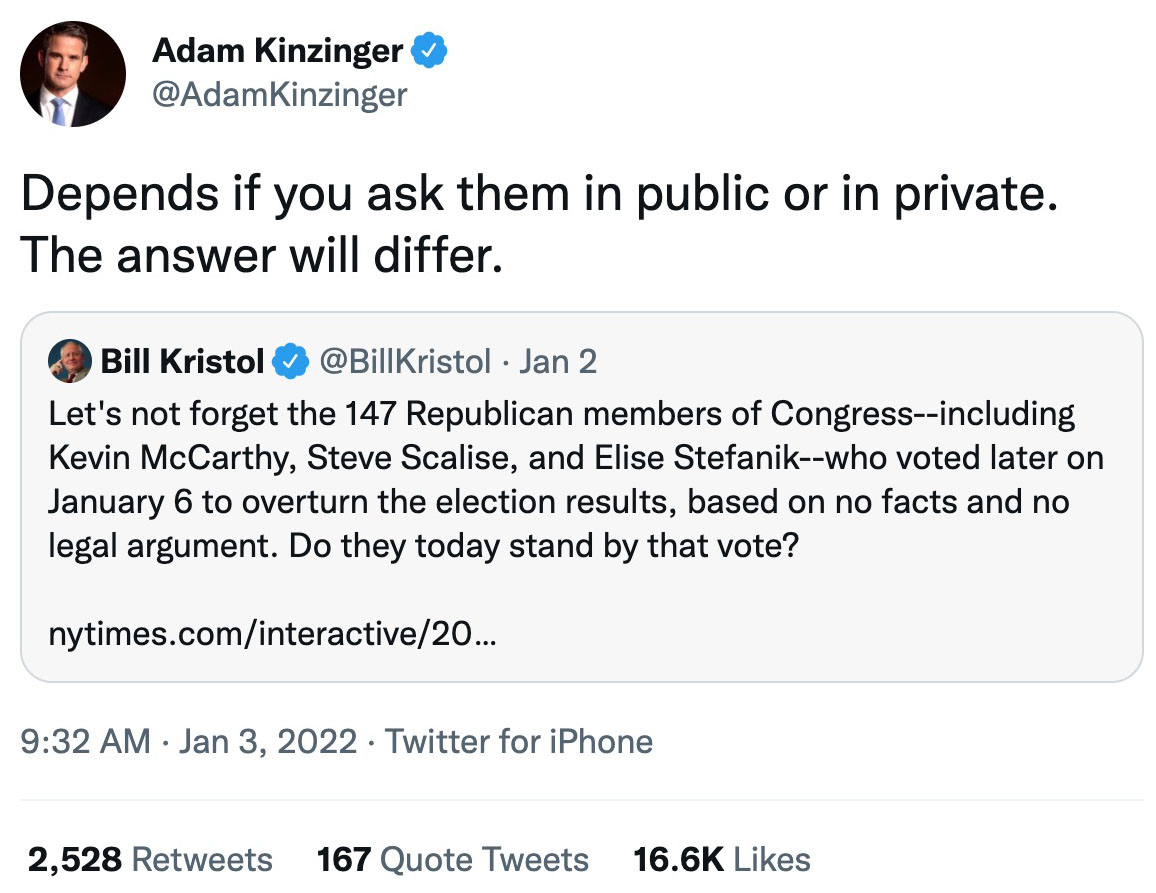

Rep Adam Kinzinger 2022 - Twitter

Rep Adam Kinzinger 2022 - Twitter

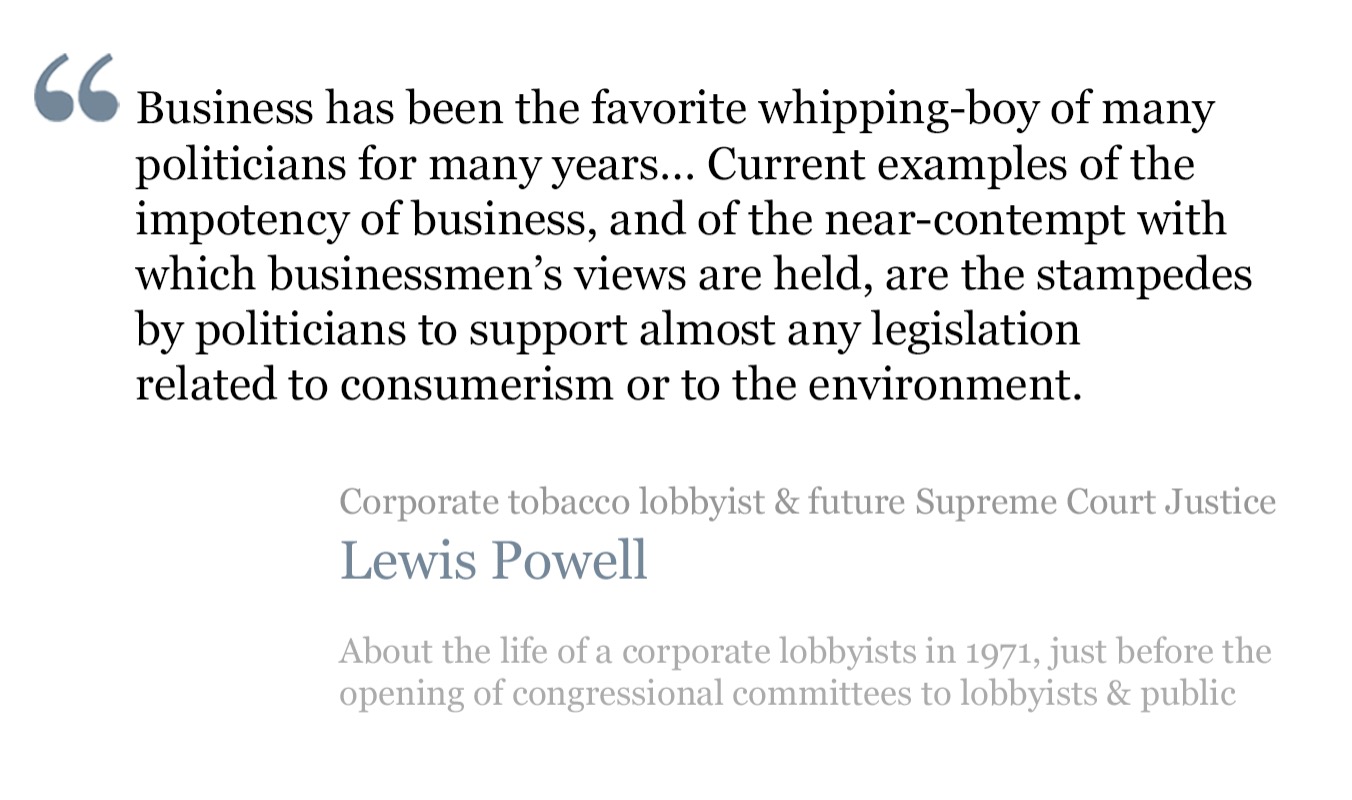

The enactment of the ‘sunshine’ laws, which had opened up committee legislative drafting sessions to the public in order to dilute the power of business lobbyists, had precisely the opposite effect. They enabled business lobbyists to monitor the votes of each elected official more closely.David Vogel 1989

The Political Power of Business

Some former sticklers for sunshine agreed with members who said bills were better when drafted away from lobbyists’ watchful eyes. Conversely, as some of these lobbyists sensed a slippage of their influence over the bill-writing process, they became the 1980s’ proponents of sunshine in Congress.Jaqueline Calmes 1987

Congressional Quarterly – Fading Sunshine Reforms

The history of US diplomacy has shown that secrecy often is essential for successGraham Allison 2018

The Case for Secret Diplomacy

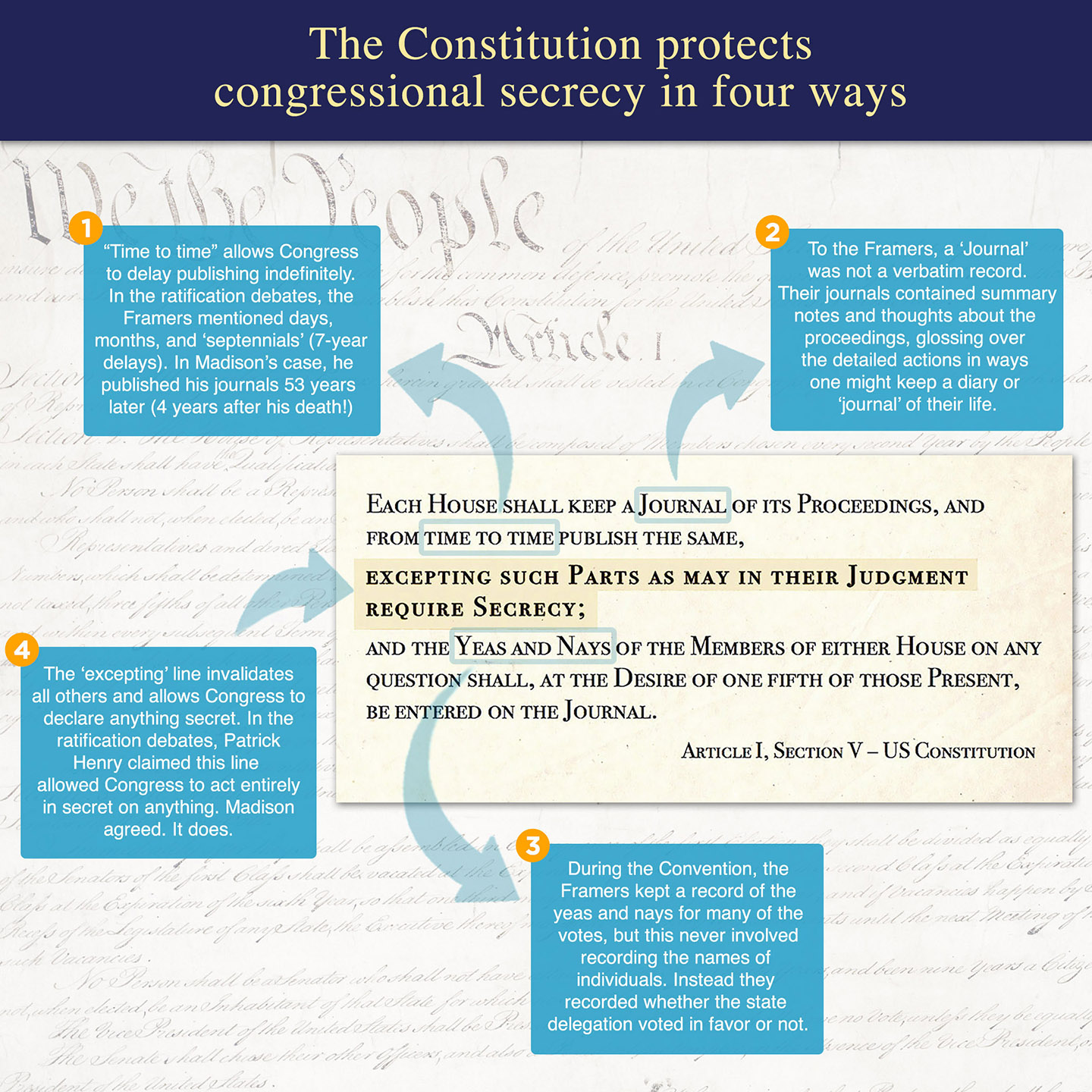

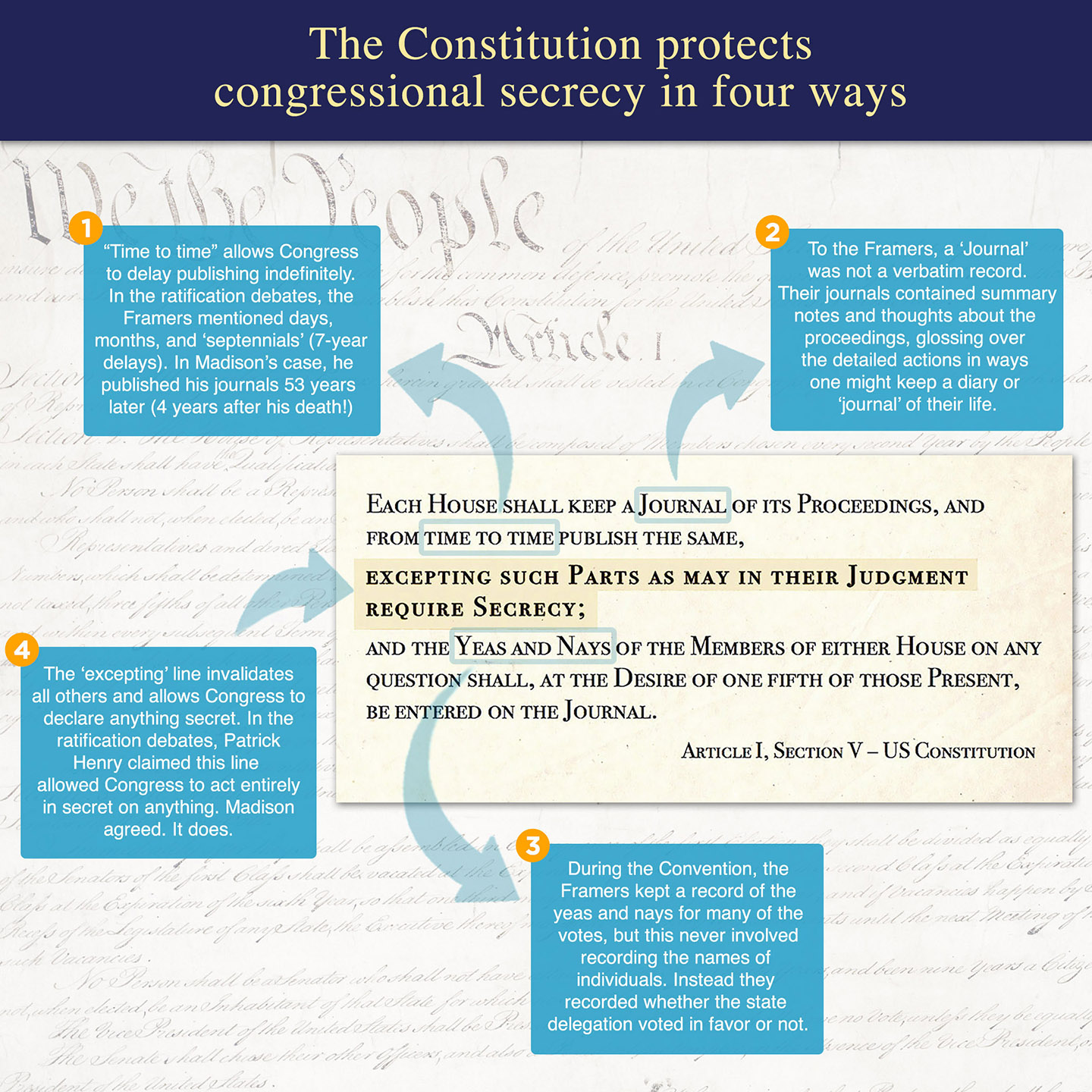

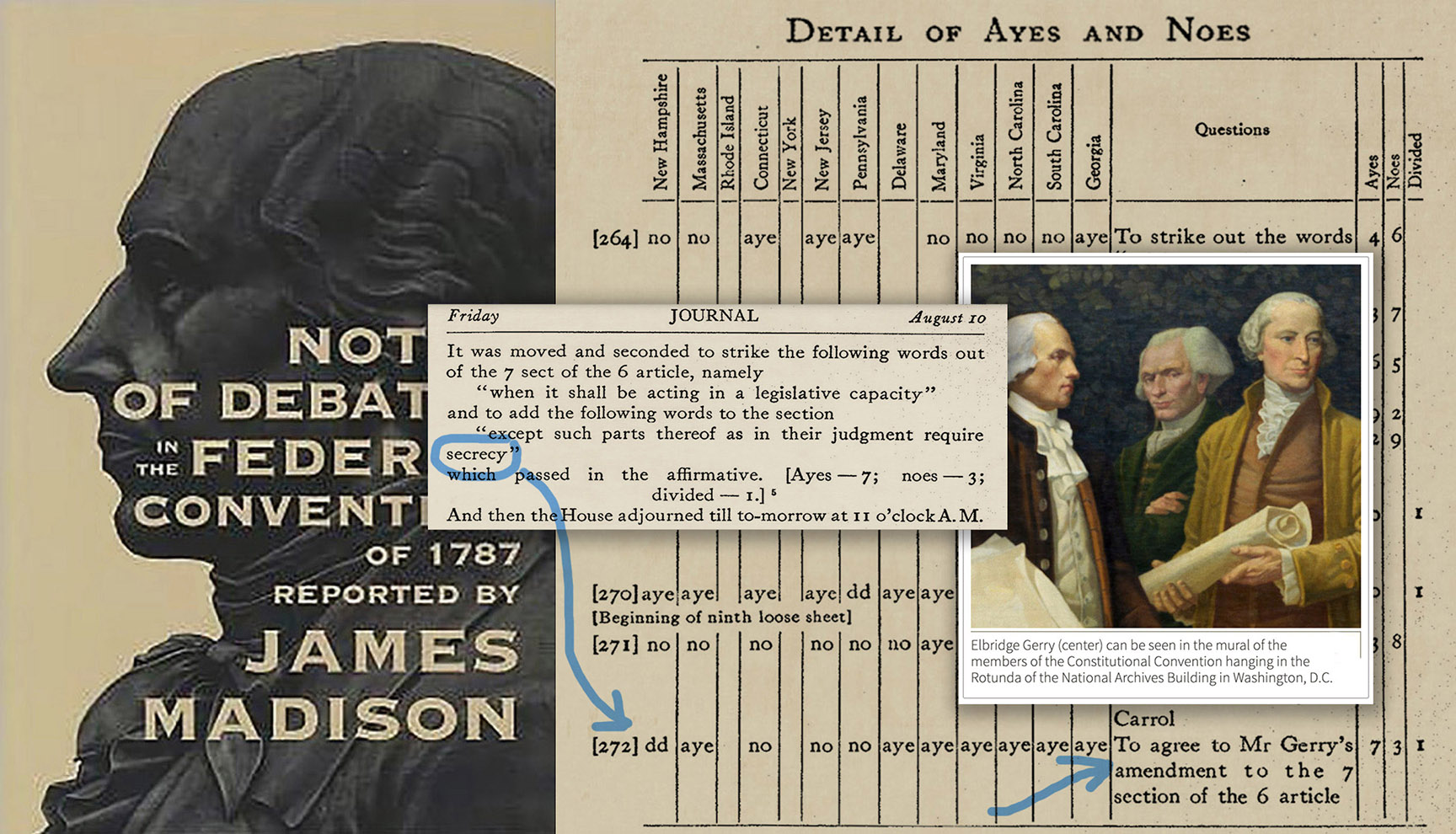

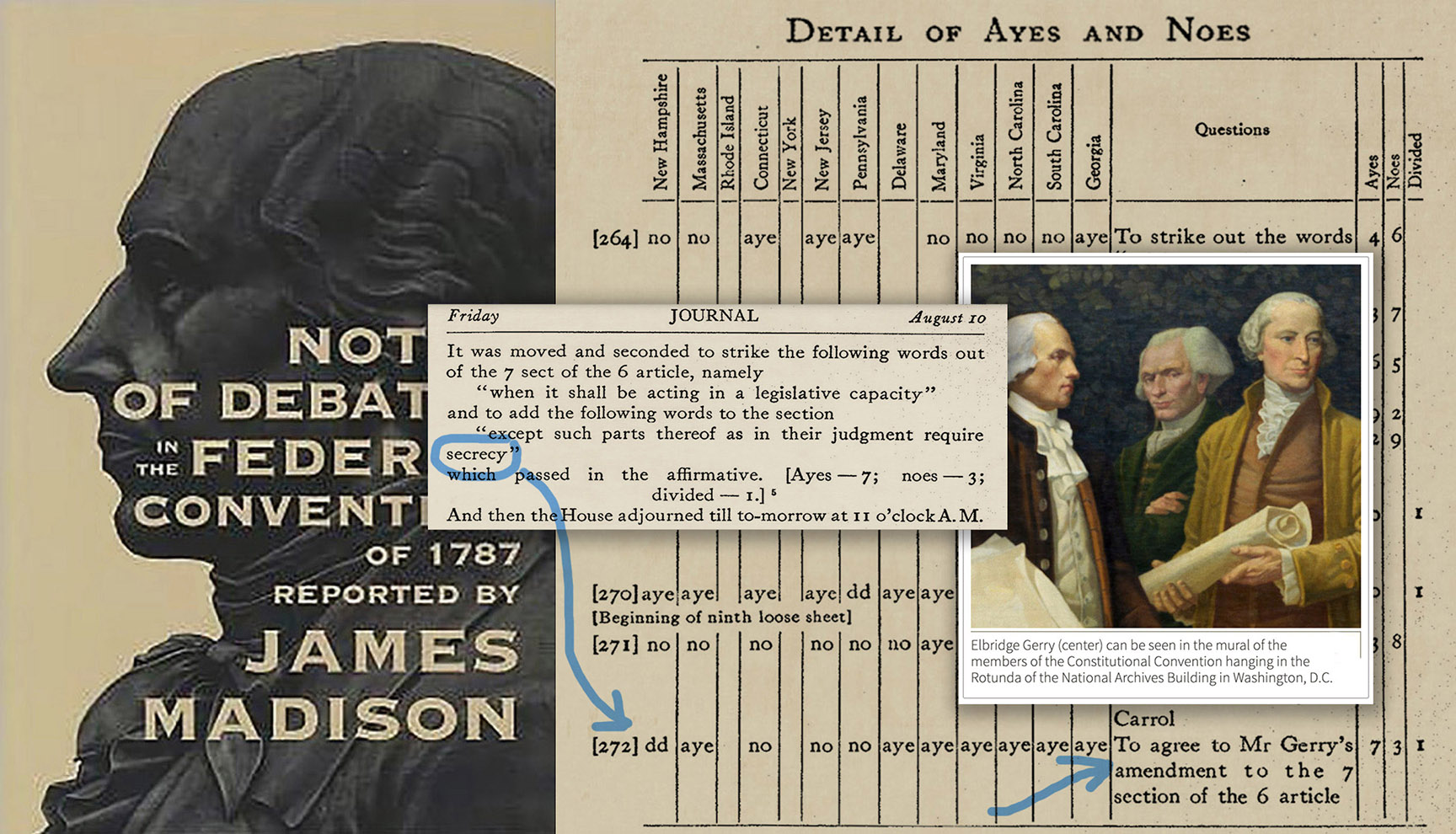

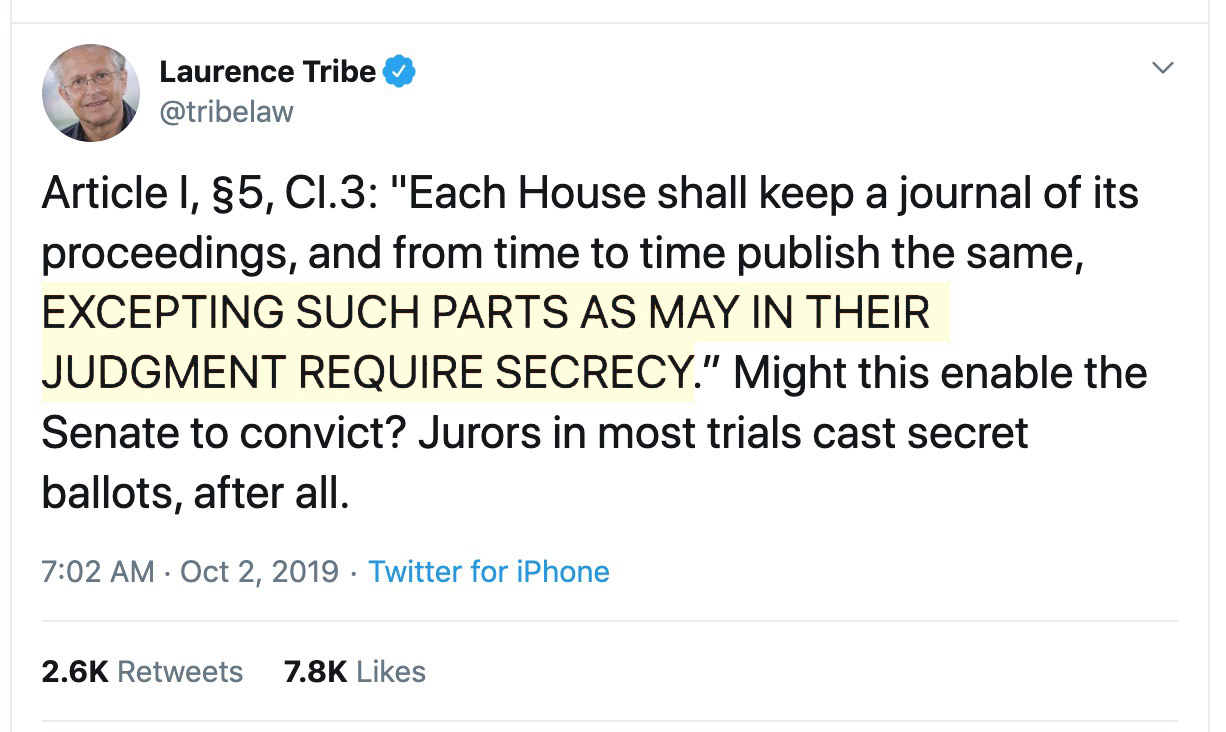

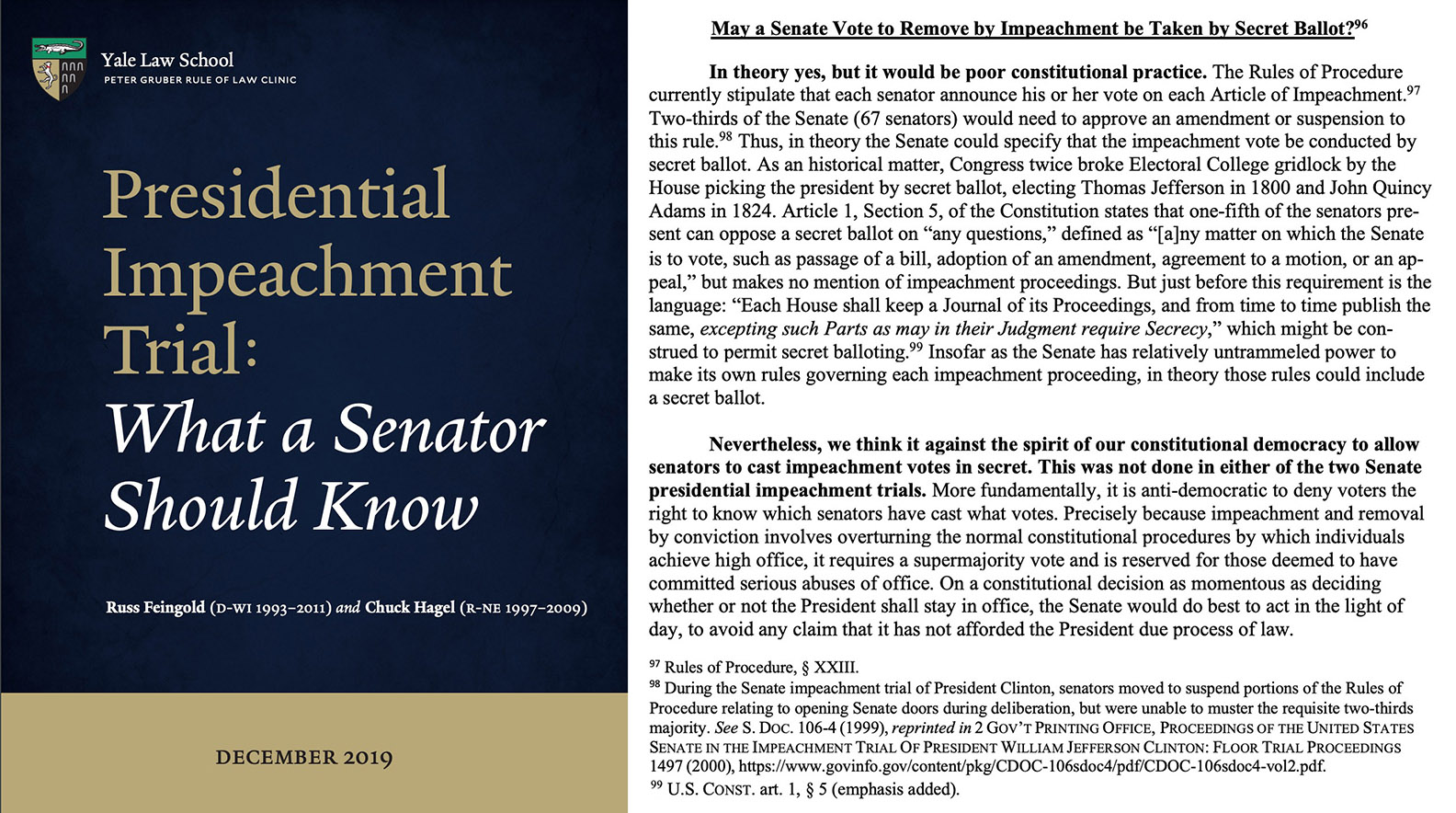

The US Constitution endorses Secrecy - Article I, Section V, Clause III

“Evil geniuses of darkness!” In 1787, while in session at the Constitutional Convention, hecklers railed into the Framers for their decision to draft the Constitution in abject secrecy - a closed-door process that took four months. But these jeers did not prevent the Framers from adding the ‘Secrecy Clause’ to the wording on the legislative branch. Article 1 Section 5 Clause 3 insures unlimited secrecy to Congress alone. Article II and Article III (executive and judicial branches) contain nothing with respect to ‘discretion’ or secrecy. And while lines 1 and 3 of the secrecy clause appear to lean on the side of transparency, line 2 (highlighted above) is the dominant line. Line 2 provides an unlimited exception to keeping and publishing the journal. This results in a clause that isn’t just wildly permissive of secrecy, but one that provides for as much secrecy as Congress may seek - be it secret ballots, executive sessions, closed door hearings, Committee of the Whole, etc. There are numerous pundits who get this wrong. Beginning with Supreme Court justice Joseph Story in the early 1800s, there has been an array of insiders suggesting that these lines instead require Congress to act transparently. Article 1 Section 5 Clause 3 is, as they argue, a requirement for both recording votes and publishing them. But these ‘transparency’ pundits generally have one thing in common: they provide their commentary on this clause as part of a larger commentary of the entire constitution. This is not an easy task. And these works (including Story’s and recently a video series by current Senator Mike Lee) usually requires volumes or hours of attention, as specific aspects of the Constitution (the Bill of Rights in particular) have generated thousands of pages of legal argumentation and interpretation. As such, these generalists often make quicker/glancing interpretations of the clauses that have received lesser attention in the courts and the press. The Secrecy Clause is one such under-the-radar clause. And nowhere in their commentaries do they tackle the clear exception to transparency provided by line 2. Further, even without the second line, the secrecy clause might still be seen as embracing secrecy. This is because there are two important and sometimes befuddling exceptions to transparency in lines 1 and 3. In line one, the Journal must be published from ‘time to time.’ Well, what does this mean? In the ratification debates, ‘time to time’ was understood as not just intentionally vague but also a way to delay publishing by septennials (7-years) or more. The wording ‘time to time’ is also a noted switch from what appeared in the Articles of Confederation, which required a ‘monthly’ publication. And Madison famously published his journals of the Convention posthumously, 53 years after the Convention. Clearly, he embraced long delays. In line three there is another befuddling clause. Line 3 requires that the ‘yeas and nays’ be entered in the Journal if requested by 1/5th of those attending. But what do the ‘yeas and nays’ mean? In the Framers’ time, it often required just a simple accounting of the vote totals – one total for those who for the provision and one total for those who voted against. Other times, the ‘yeas and nays’ meant a recording of the various delegates’ names with their individual votes attached. But the Constitution provides some clarity in a manner which sides on this notion of the simple printing of vote totals. This is because later in Article 1, Section 7, Clause 2 the Constitution again calls for the ‘yeas and nays’ and then states “and the names of the persons voting for and against the bill shall be entered on the journal.” This means that if the ‘yeas and nays’ were intended to be an individual recording of each member’s votes, this clause would have an odd redundancy that didn't appear earlier in Section 5. So even without line 2, the Secrecy Clause may be interpreted as providing for a broad amount of secrecy - publishing delays of up to fifty years and a Journal in which only vote totals are published. But these last two arguments are just that - arguments. As we cannot know the intentions of the Framers, we will have to accept that the ambiguity of lines 1 and 3 could easily be interpreted as an embrace of transparency. Line 2, however, doesn’t have the same amount of wiggle room. The exception it provides to all aspects of transparency is clear and strong. Hence the Secrecy Clause of the Constitution is just that, a guaranteed right to congressional secrecy. Even in the Ratification Debates of 1788, it was treated this way, when Patrick Henry railed against the unlimited secrecy this clause provided. The Journal Clause is the Secrecy Clause.

The US Constitution endorses Secrecy - Article I, Section V, Clause III

Members can make a decision they would not otherwise make with the lobbyists peering at them...Rep. Don Pease 1984

Privacy Called Spur to Tax Bill (NY Times)

Sunshine laws kid the public… legislative compromises and accommodations must also be provided for, and these require privacy [secrecy]. “If we have to meet in our wives’ boudoirs – if they still have such things – we will.”Richard Bolling (D.Mo) 1976

Reform Penetrates Conference Committees

Congressional reforms, particularly the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970, reduced the power of committee chairs and opened Washington to a barrage of interest group activists, lobbyists, and campaign funders.Benjamin C. Waterhouse 2014

Lobbying America

Clarity and publicity kill… Officials who need to fear that their internal deliberations will be made public are less positioned to make effective public policy.Jerry Z. Muller 2018

The Tyranny of Metrics

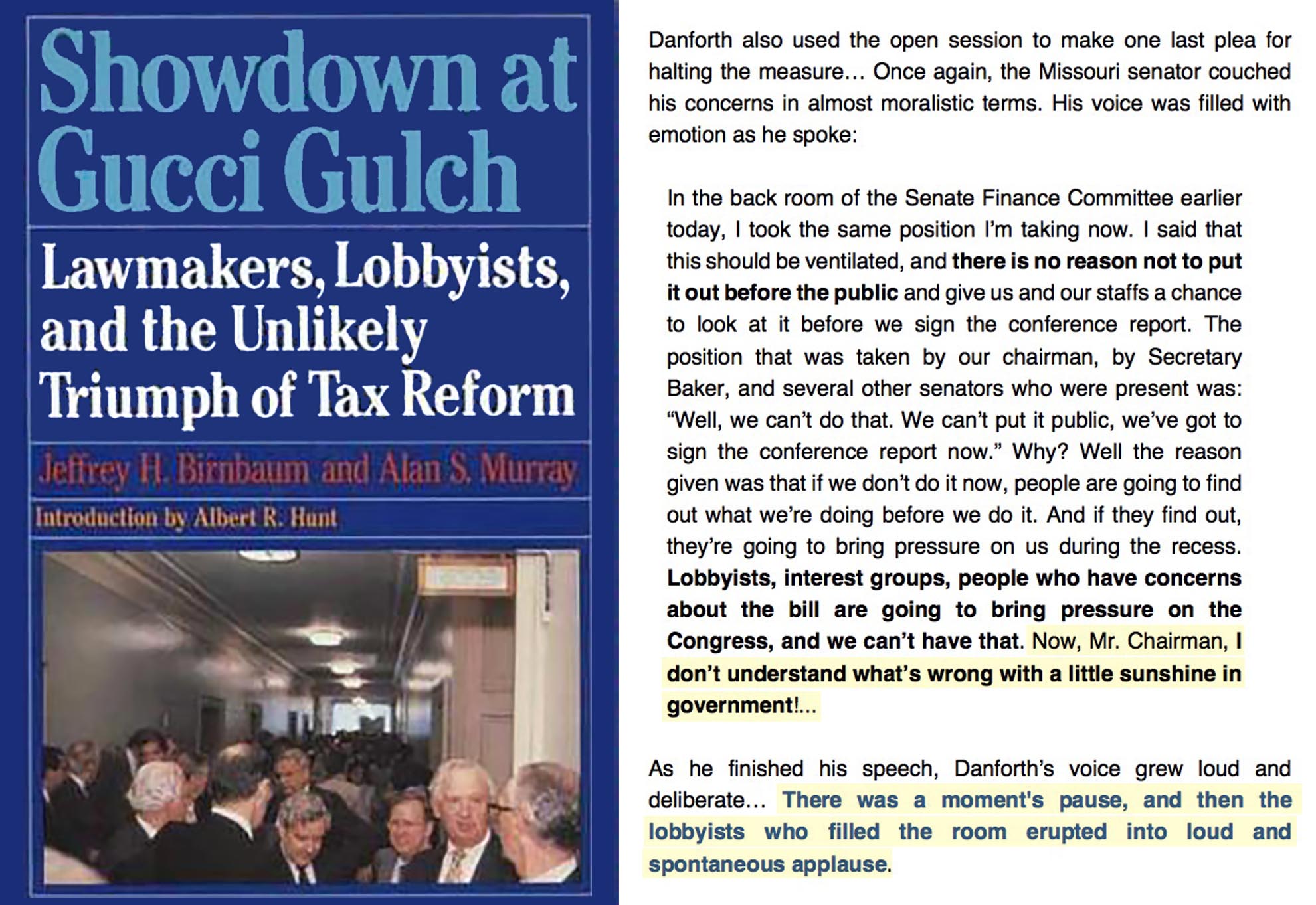

Jeffrey Birnbaum 1988 - Showdown at Gucci Gulch

Lobbyists applauding sunshine speech by Senator John Danforth

Jeffrey Birnbaum 1988 - Showdown at Gucci Gulch

Lobbyists applauding sunshine speech by Senator John Danforth

Since the Sunshine Rule, markup sessions are very popular events in the legislative process… Cueing up for a markup, and sweating the markup line is part of the lobbyist’s job. John Zorack 1990 (Lobbyist)

The Lobbying Handbook

In the 1970s, we junior members argued strongly for openness, as did the media. But we discovered that people posture and abandon the responsibility of legislating.Rep. Philip Sharp 1990

American Government and Politics

Intrigue and cabal are thus deprived of some of their main resources, by plotting and devising measures in secrecy...Mr. Justice Blackstone seems, indeed, to suppose, that votes openly and publicly given are more liable to intrigue and combination (corruption), than those given privately and by ballot.Joseph Story 1833 (Supreme Court)

Commentaries on the Constitution

For any speech or debate in either house, [members of the House and Senate] shall not be questioned in any other place.US Constitution 1789

Speech or Debate Clause - Article I Section VI

Russell Berman 2022 - Atlantic Magazine

Russell Berman 2022 - Atlantic Magazine

Voters and interest groups can monitor recorded votes much more easily than other types of legislative behavior. Consequently, the extent to which voters and interest groups can hold individual legislators to account depends on the use of roll-call procedures.Clifford Carrubba, Matthew Gabel & Simon Hug 2008

Legislative Voting Behavior, Seen and Unseen: A Theory of Roll-Call Vote Selection

Full transparecny of politicans’ actions does not increase the quality of political representation.David Stadelmann, Marco Portmann and Reiner Eichenberger 2014

Transparency Does Not Increase the Quality of Political Representation

Empirical results indicate that making it easier to identify individual votes and actions of politicians does not necessarily improve the quality of representation in terms of aligning political decisions and voter preferences more closely.David Stadelmann, Marco Portmann and Reiner Eichenberger 2014

Transparency Does Not Increase the Quality of Political Representation

David Stadelmann, Marco Portmann and Reiner Eichenberger 2014 - Transparency Does Not Increase the Quality of Political Representation

David Stadelmann, Marco Portmann and Reiner Eichenberger 2014 - Transparency Does Not Increase the Quality of Political Representation

The leading Republican members should come to an understanding, close the doors, and determine not to separate till the vote is carried and all the secrecy you can enjoin should be aimed at until the measure is executed.Thomas Jefferson 1811

Letter to John Wayles Eppes

A dogmatic approach toward transparency may ultimately prove counterproductive to the reform cause if seemingly public opportunities serve the interests of the few more often than the majority.Bruce Cain 2014

The Transparency Paradox

“The average American does not come down to these meetings,” Mr. Conable added. “It’s the lobbyist,” he said, who in an open session can pinpoint the committee members whose position they want to change. “During any break, they have to be physically restrained from contacting us,” he said, “and we sit there and watch them wince as we violate our alleged deals with them.”

“So, as with the tax-shelter legislation we passed, good legislation is produced by the closed meeting,” he added. He also said he did not think the move to increase by a third the tax on liquor would have been approved in the open “because the distilled-spirit people would have been out there jumping up and down and sending us messages.”Jonathan Fuerbringer 1984

Privacy Called Spur to Tax Bill (NY Times)

A requirement that public officials deliberate matters among themselves in open meetings makes it difficult and unwieldy for officials to discuss issues among themselves, but easy to discuss them with non-public officials such as lobbyists and other special interests, which in turn can elevate the influence of those who have access to legislators as a result of their wealth, status, or political connections.John F. O’Connor & Michael J. Baratz 2004

Some Assembly Required: The application of state open meeting laws to email correspondence.

Legislative openness may enable special interest groups to orchestrate for themselves narrow legislative deals not in the public interest.Steven F. Huefner 2003

The Neglected Value of the Legislative Privilege in State Legislatures

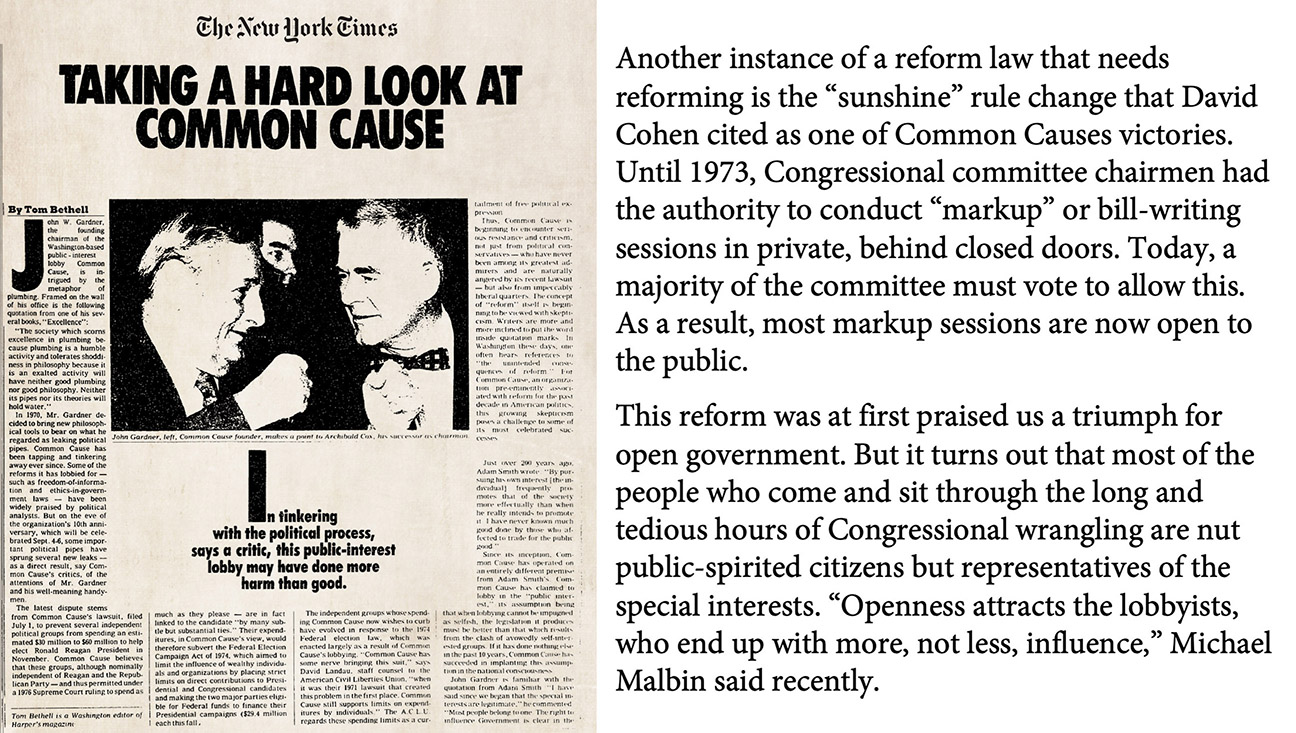

Martha Hamilton 1984 – Washington Post 1984 – Opening Up Congress (pdf)

Martha Hamilton 1984 – Washington Post 1984 – Opening Up Congress (pdf)

And therefore no great Popular Common-wealth was ever kept up; but either by a forraign Enemy that united them; or by the reputation of some one eminent Man amongst them; or by the secret Counsell of a few; or by the mutuall feare of equall factions; and not by the open Consultations of the Assembly.Thomas Hobbes 1641

Leviathan

Said one committee member, on the difficulty of writing tax legislation in public sessions: “You’re not going to solve problems in front of an audience” Randall Strahan 2011

The New Ways and Means

Still, members of the Finance Committee and its staff were worried last week about the problems of open sessions and lobbyists… Even before the committee adjourned Thursday, the lobbyists had been at work. Reports are that votes are already changed and the committee may reverse itself this week. Mr. Dole noted the open-session problem himself… he told an aide: “The lobbyists are like flies here.”Jonathan Fuerbringer 1984

Privacy Called Spur to Tax Bill (NY Times)

Alan Fram 2022 - Closed-door deal on gun control, breaks Senate logjam

Alan Fram 2022 - Closed-door deal on gun control, breaks Senate logjam

[In closed sessions] members are more candid and deal with the tougher issues without worrying about being sensitive to the various pressures on them. The lobbyists have less influence.John J. Salmon 1984

Privacy Called Spur to Tax Bill (NY Times)

By closing meetings where important decisions are taken by elected leaders (and others), or by making such situations nontransparent in other ways, leaders are freed of base incentives to pander and posture to those outside and are directed to pursue those policies that best effect the public interest.John Ferejohn 2015

Secret Votes and Secret Talks

The result of the closed meetings is that you get better legislation.John J. Salmon 1984

Ways and Means Committee: Behind Closed Doors (Dale Tate)

Lobbyist Jack Abramoff - On trading public votes 2011

Lobbyist Jack Abramoff - On trading public votes 2011

Closed door meetings afford more frank and cand id discussions. Members are much more willing to feel free to say things they would never say in public - a particular problem they might have because of a constituent, forinstance. And members are more likely to say, ‘Let me ask a dumb question.’John J. Salmon 1984

Ways and Means Committee: Behind Closed Doors (Dale Tate)

Committees should work more often in execu tive committee session; greater secrecy would improve the chances of free flowing debate and genuine consideration of alternatives.Daniel J. Palazzolo 2017

Return to Deliberation

I find that secrecy can 1) result in outcomes that are less likely to be sabotaged, 2) result in less socially inefficient use of resources by interest groups, and 3) shorten the bargaining process.Barbara Koremenos 2010

Open Covenants, Clandestinely Arrived At

Rep Rob Woodall 2019 - House Modernization

On March 27, 2019, The Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress and the Modernization Committee of the GOP discussed the pitfalls of transparency during a hearing about congressional reforms. And at 1:05:06, Representative Rob Woodall appears to become the first member in the history of the US Congress to openly question the 1970s sunshine laws. He suggests that increased transparency might be at the root of a number of institutional problems with Congress. Here is Woodall’s statement:

“Well I thought that was interesting in Mr. Wolfensberger’s testimony, he said he’s got six things that make these reform efforts successful. By my count four of the six things were things too much transparency might threaten 1. private informal meetings are necessary 2. check your partisan guns at the at the door 3. soliciting views from other members who are not on the on the panel 4. flexibility and the ability to compromise. At some point you know the reason I can’t take pictures on the second floor of the Capitol is you never know who I might be talking to and I want the freedom to be able to talk to who I want to talk to. We don’t have that dynamic. Zoe [Representative Zoe Lofgren] said we’re not gonna roll back cameras on the floor. I’m sure that’s true. It might have been, who mentioned transparency, it was you Mr. strand. Are we at a point where we have so many other ways to communicate to get the word out that it would be okay to dial back on some degrees of transparency because we’re highlighting that transparency elsewhere?”

Unfortunately Woodall directs the question to Mark Strand who evades, immediately turning the conversation elsewhere. But Strand he was followed by Don Wolfensberger who takes up the question saying that transparency is “a double edged sword.”

Rep Rob Woodall 2019 - House Modernization

“Well I thought that was interesting in Mr. Wolfensberger’s testimony, he said he’s got six things that make these reform efforts successful. By my count four of the six things were things too much transparency might threaten 1. private informal meetings are necessary 2. check your partisan guns at the at the door 3. soliciting views from other members who are not on the on the panel 4. flexibility and the ability to compromise. At some point you know the reason I can’t take pictures on the second floor of the Capitol is you never know who I might be talking to and I want the freedom to be able to talk to who I want to talk to. We don’t have that dynamic. Zoe [Representative Zoe Lofgren] said we’re not gonna roll back cameras on the floor. I’m sure that’s true. It might have been, who mentioned transparency, it was you Mr. strand. Are we at a point where we have so many other ways to communicate to get the word out that it would be okay to dial back on some degrees of transparency because we’re highlighting that transparency elsewhere?”

Unfortunately Woodall directs the question to Mark Strand who evades, immediately turning the conversation elsewhere. But Strand he was followed by Don Wolfensberger who takes up the question saying that transparency is “a double edged sword.”

On Oct. 22, 2014 the Earth Institute hosted a panel discussion on the Origins of Environmental Law, featuring Leon Billings and Thomas Jorling, the two senior majority and minority staff members who led the Senate Subcommittee on Environmental Pollution which originated and developed the 1970s Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, and other major environmental/climate legislation... Jorling discussed the importance of the closed markup session – in the 1970s, laws were written behind closed doors, resulting in a high degree of cooperation. Senators were free to ask questions and discuss issues openly without fear of scrutiny from others. This created a lawmaking process built on “understanding, education and learning that members actively engaged in.” Today, the open session process in lawmaking makes for better theater than an actual practice of understanding.Haley Martinez 2014

Writers of the Clean Air Act: Insight into the ‘Golden Age’ of Environmental Law

Our political institutions ought to largely operate under a veil of secrecy. By secrecy, I mean this: when representatives vote on bills (either on the legislature floor or in committee), they do so by the secret ballot.Brian Kogelmann 2021

Secret Government: The Pathologies of Publicity

It could be argued that transparent negotiations not only beget more social inefficiency, but also produce a collective action problem among the (special interest) groups themselves.Barbara Koremenos 2010

Open Covenants, Clandestinely Arrived At

“Sunshine” changes have left members visible and vulnerable to attentive publics, most often organized interests.Larry Rieselbach 1994

Encyclopedia of Policy Studies

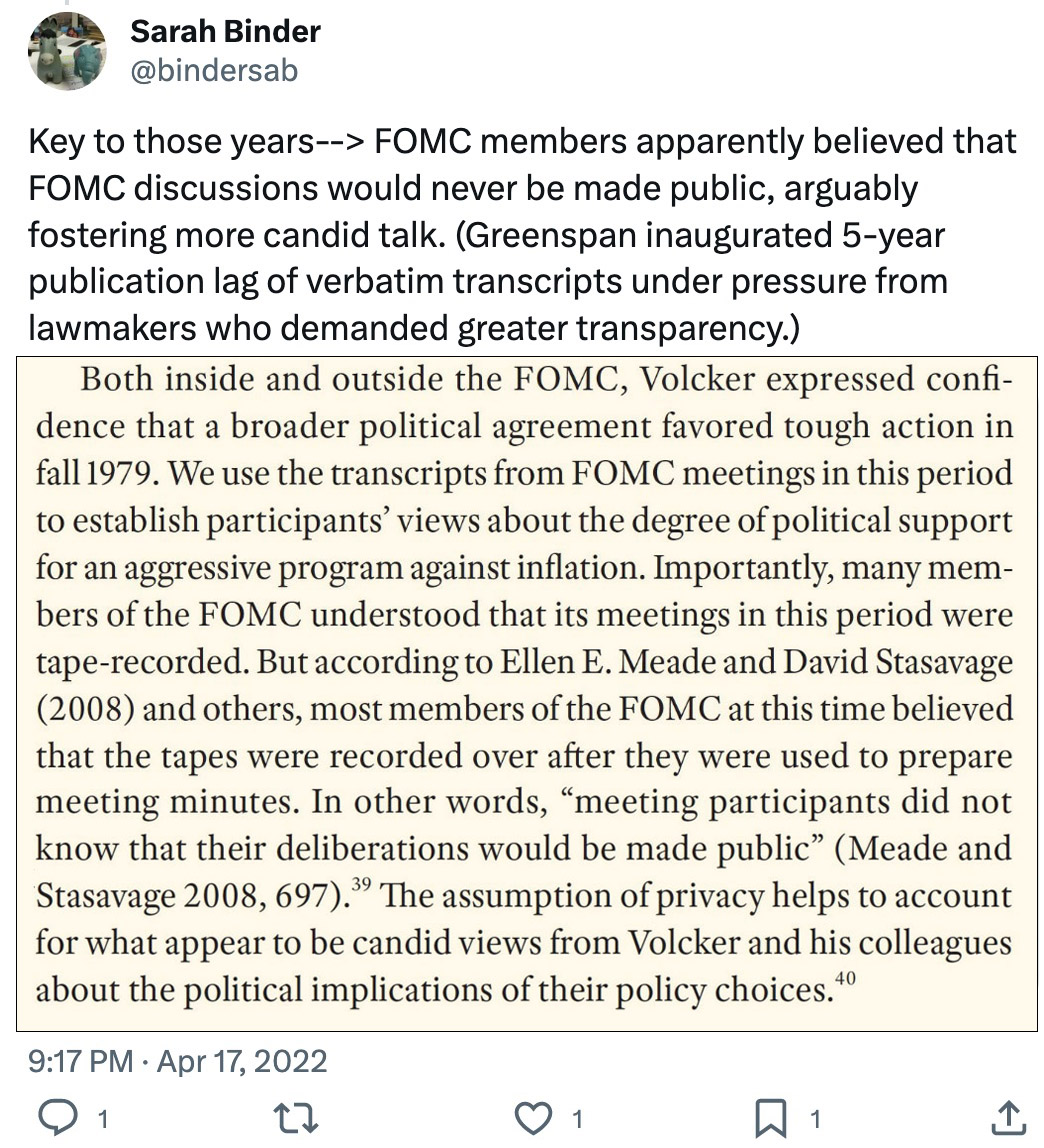

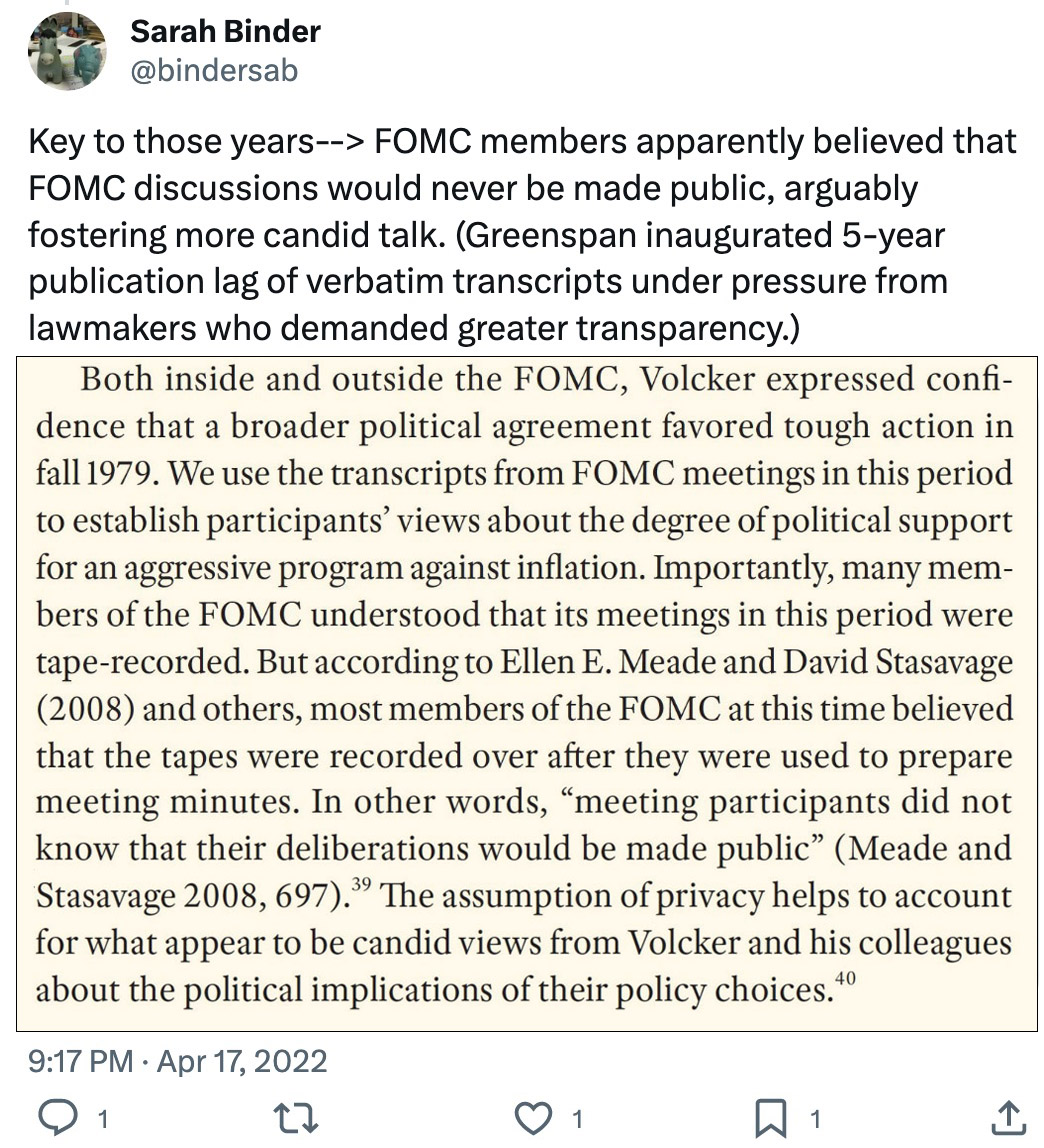

Negotiating win-win deals requires secrecy.Sarah Binder 2017

McConnell’s Secretive Lawmaking

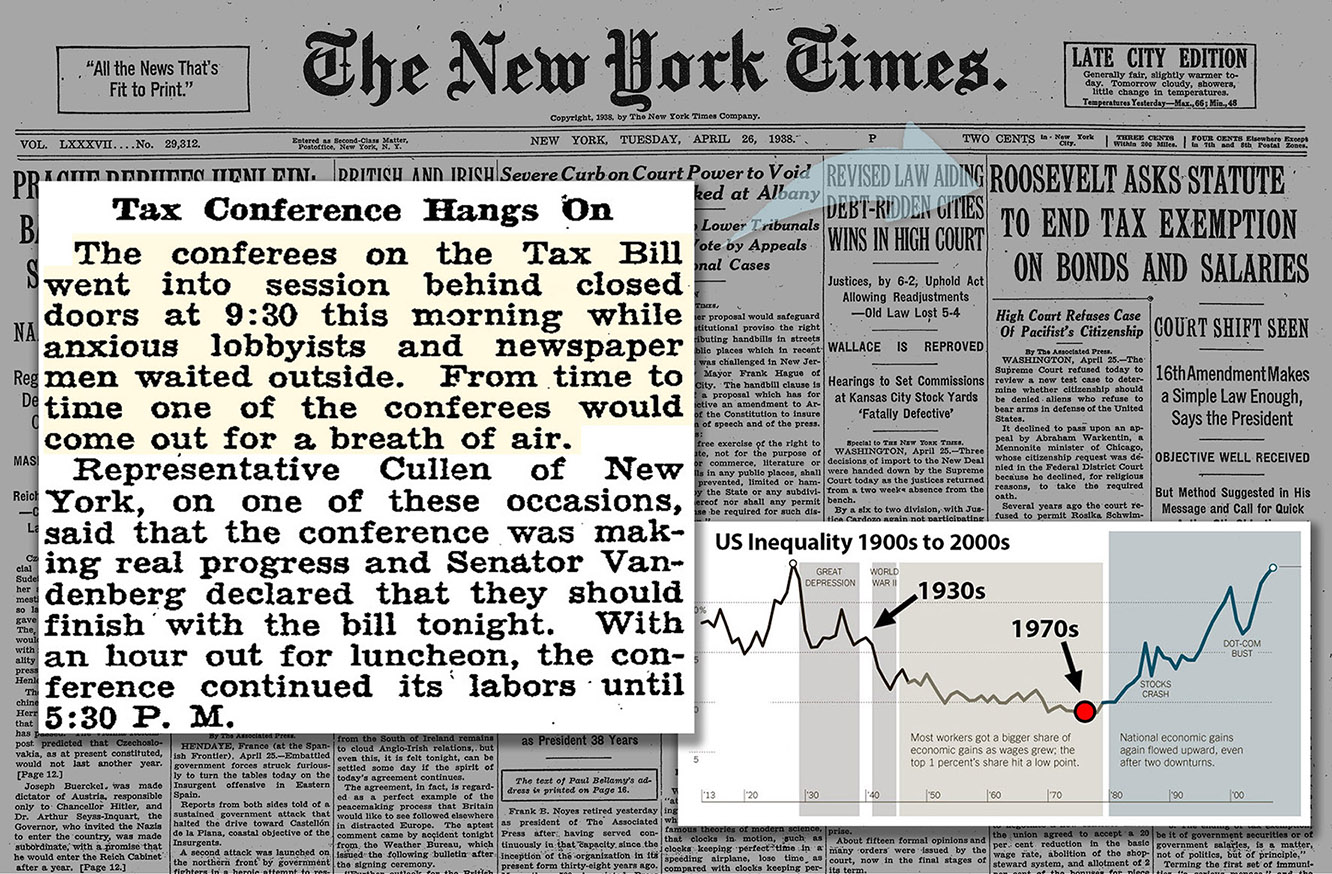

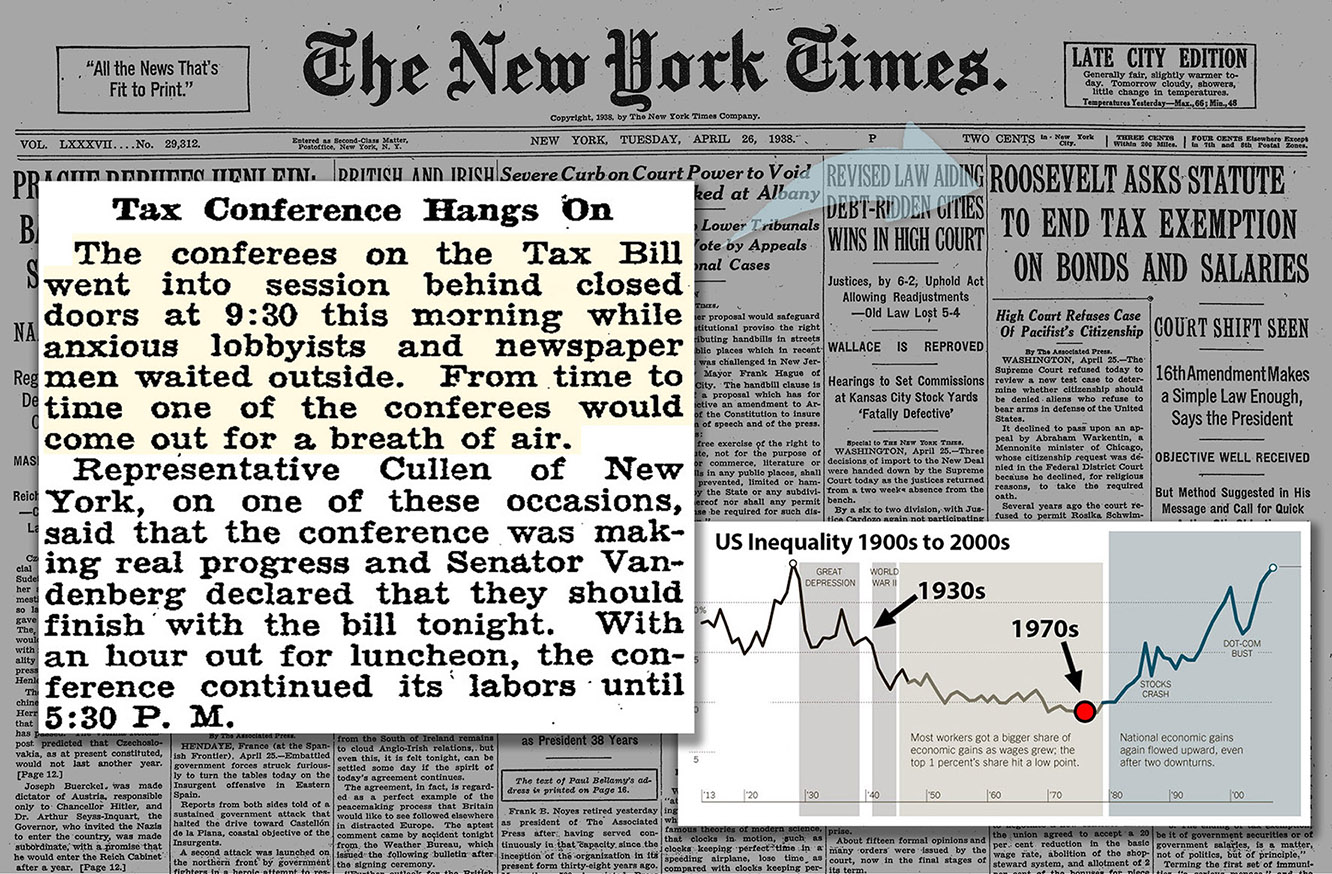

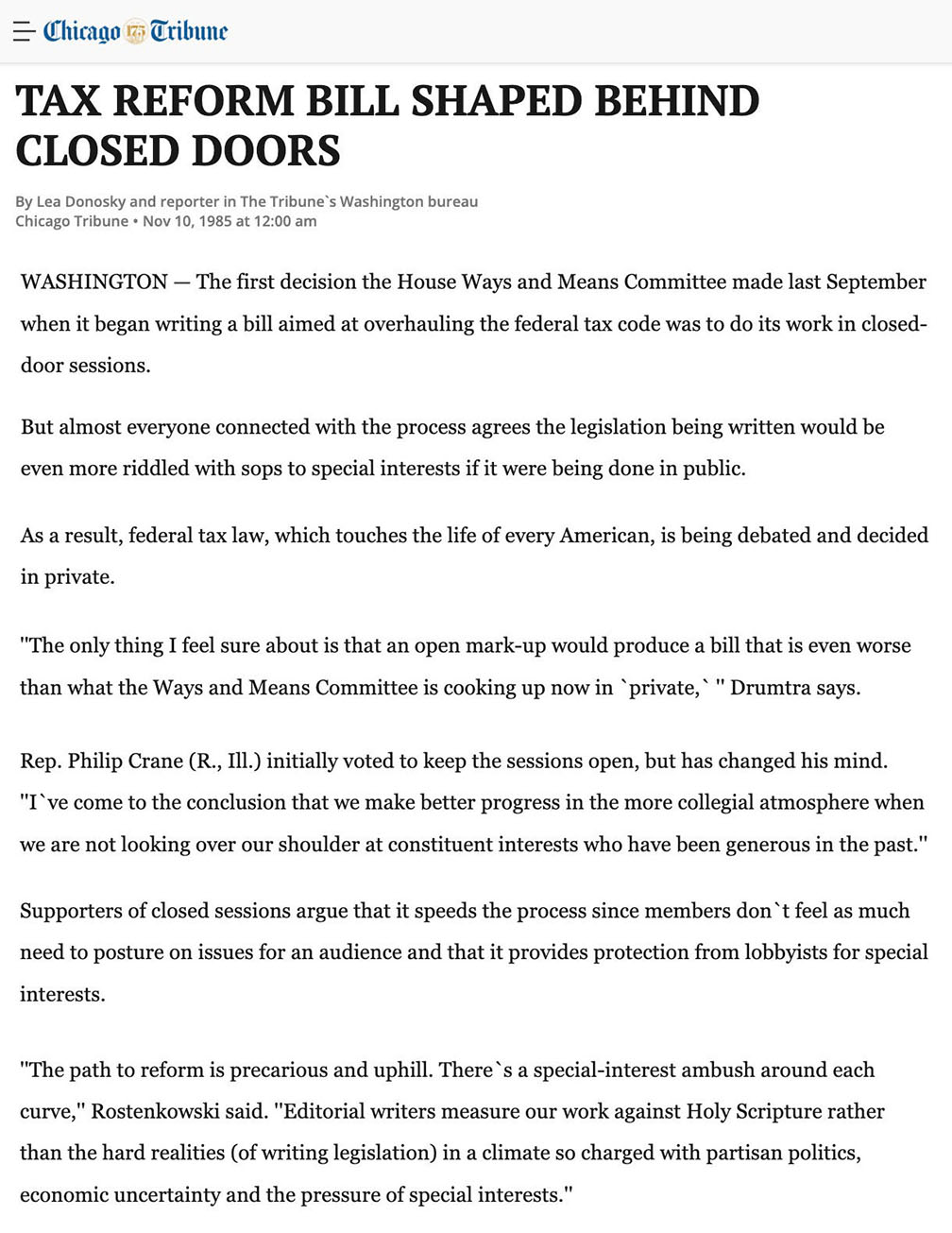

New York Times 1938 – Inequality Drops as Congress Writes Tax Laws in Secret

Text: The conferees on the Tax Bill went into session behind closed-doors at 9:30 this morning while anxious lobbyists and newspaper men waited outside. From time to time one of the conferees would come out for a breath of air. NOTE: Committees were pushed into the sunlight in 1970s with the Legislative Reorganization Act and other laws and inequality soared.

New York Times 1938 – Inequality Drops as Congress Writes Tax Laws in Secret

Transparency is a useful tool for lobbyists – it enables them to keep better track of their competitors, and to demand equal access for themselves.David Frum 2014

The Transparency Trap

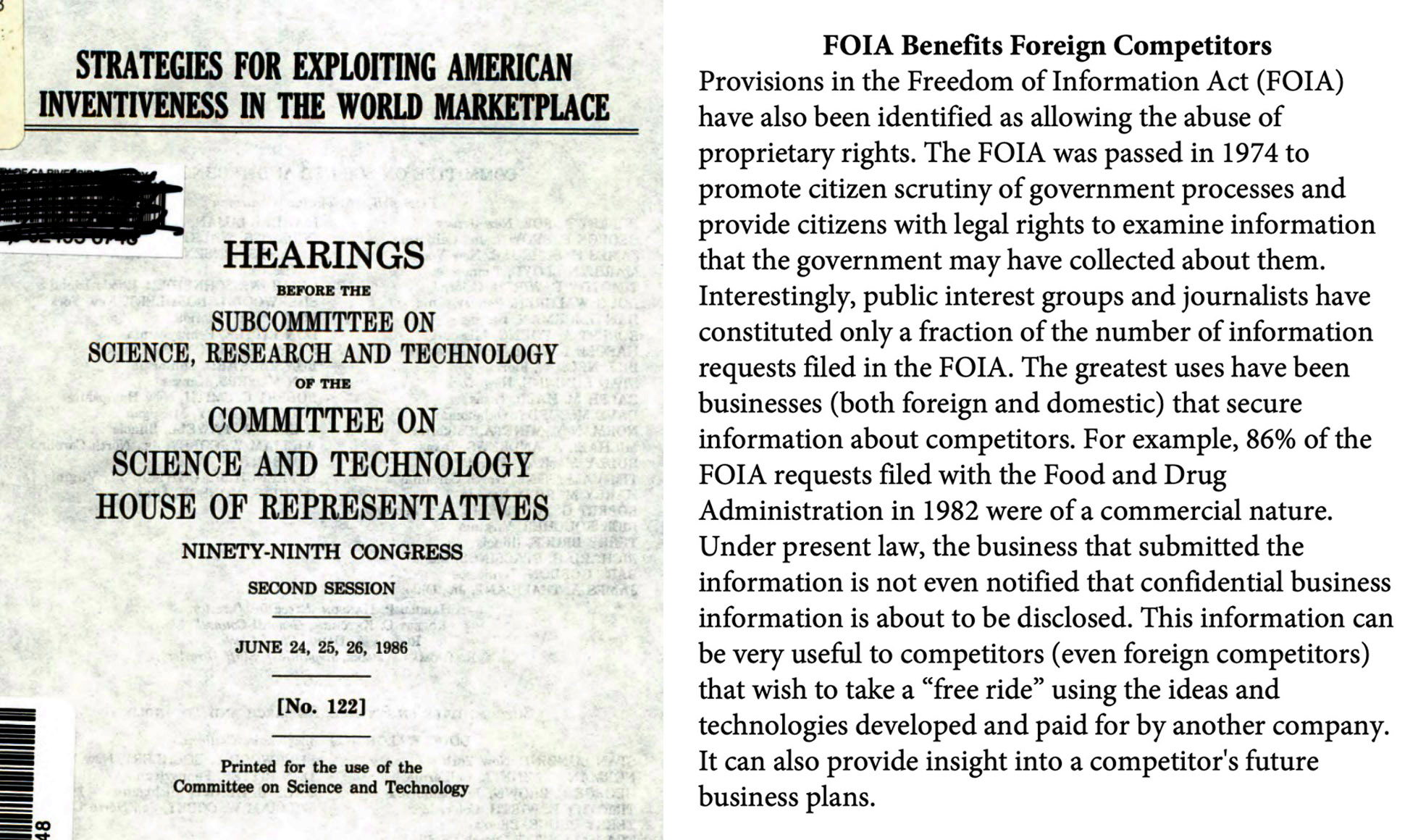

The Freedom of Information Act is one of those laws that ties the hands of government officials and makes it impossible to get government work done.Donald Rumsfeld 1966

Is Our Government Too Open (FOIA)

Anton Scalia 1982 – The Freedom Of Information Has No Clothes (FOIA, Executive)

Anton Scalia 1982 – The Freedom Of Information Has No Clothes (FOIA, Executive)

The adoption of open markup sessions, probably accounted most for exposing members to interest group pressures. Conversely, adopting closed sessions in 1983 seems to have reversed that trend.Sheldon D Pollack 1995

A New Dynamics of Tax Policy?

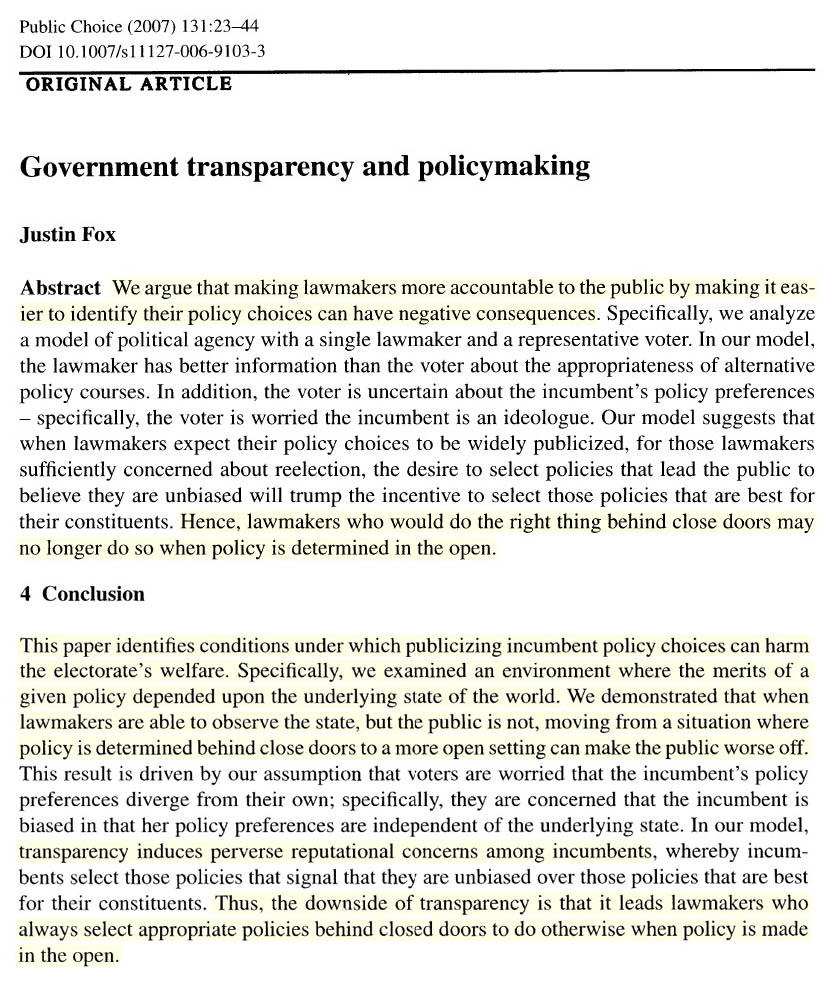

Thus, the downside of transparency is that it leads lawmakers – who always select appropriate policies behind closed doors – to do otherwise when policy is made in the open.Justin Fox 2006

Government Transparency and Policymaking

Senator Sue Crawford said one of the arguments that had been made was that secret ballots (in legislatures) encourage secret deals. “Actually, the opposite is true,” she said. “If you have a secret ballot, no one can enforce any deal, secret or not.”JoAnn Young 2015

Senators Vote to Keep Secret Ballots in Leadership

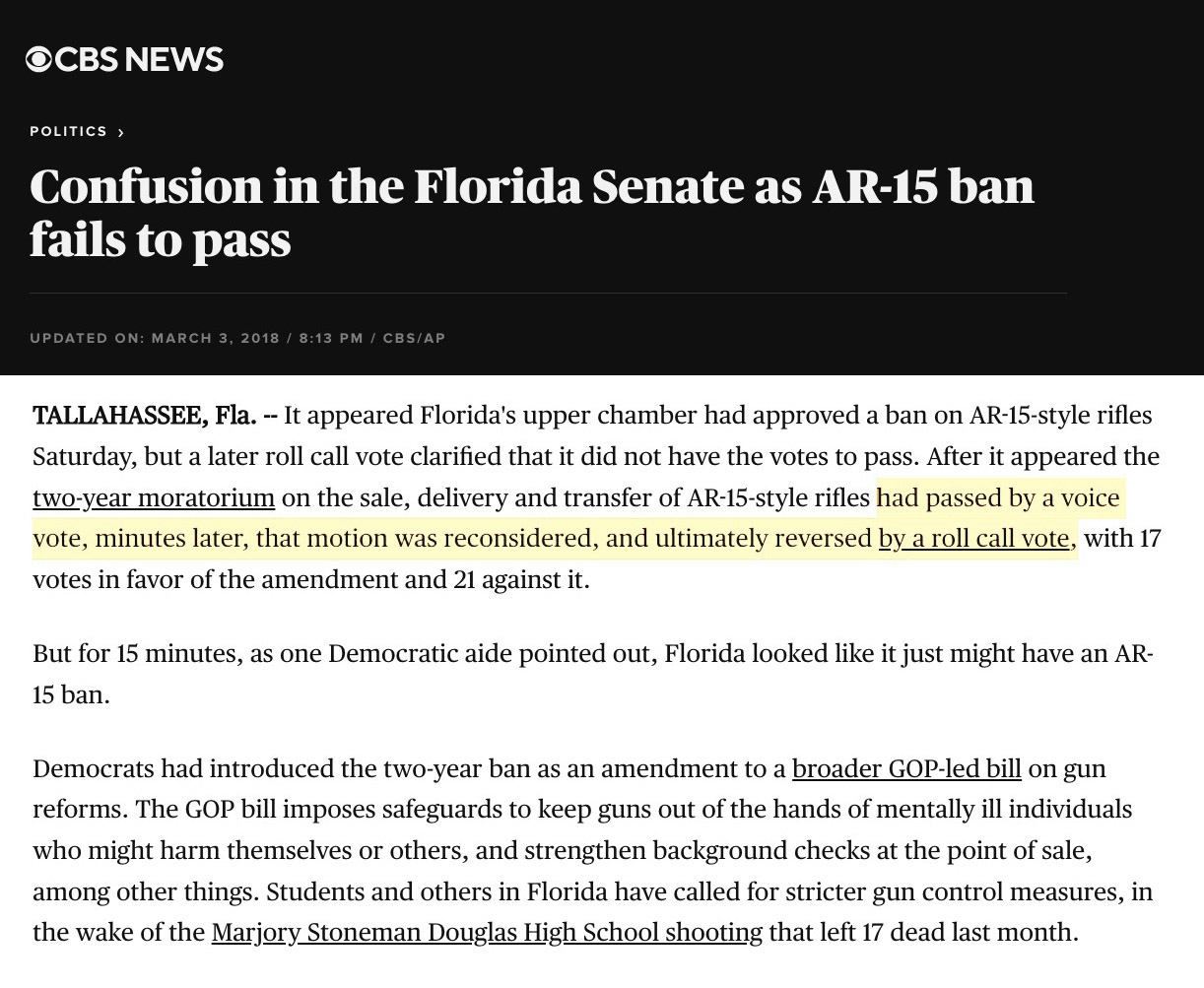

CBS 2018 - Florida Gun Control Passes on Secret Vote, Immediately Rescinded on Transparent Vote (NRA)

CBS 2018 - Florida Gun Control Passes on Secret Vote, Immediately Rescinded on Transparent Vote (NRA)

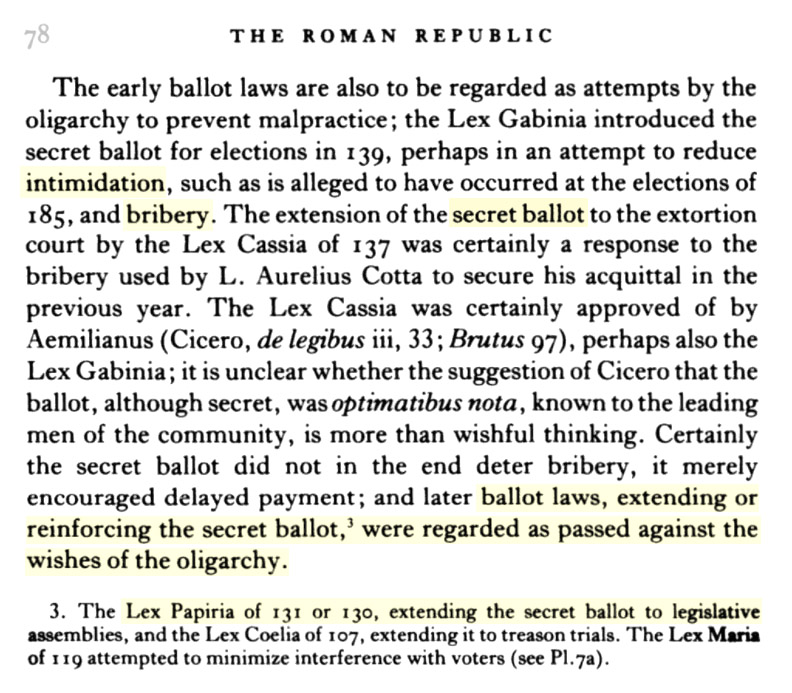

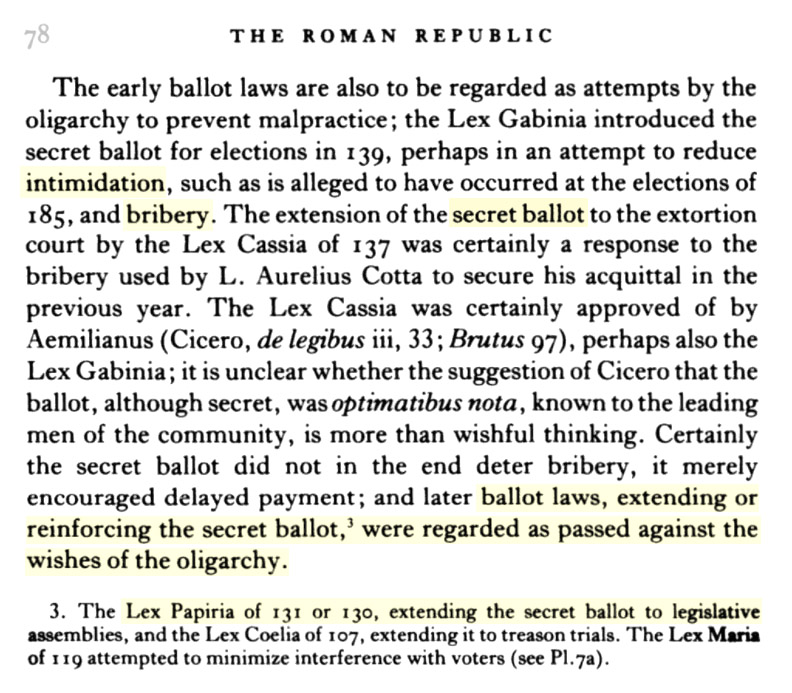

Everyone knows that laws which provide a secret ballot have deprived the aristocracy of all its influence.Cicero 50 BC

De Legibus

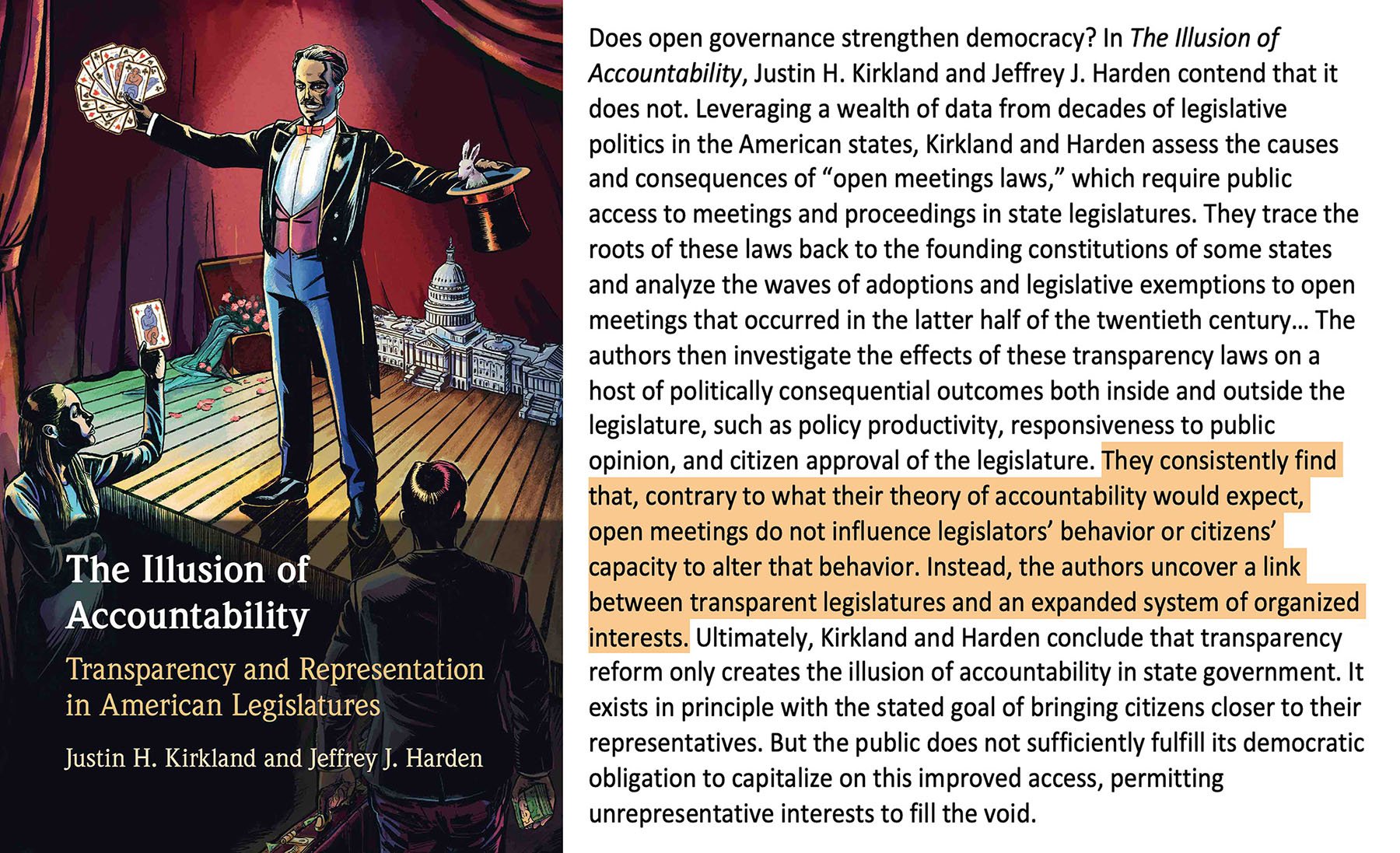

The Illusion of Accountability reveals the dark side of governing in the light: Organizing interests, not American voters, benefit from our commitments to legislative sunshine.Sarah Binder 2022

The Illusion of Accountability: Transparency and Representation in American Legislatures

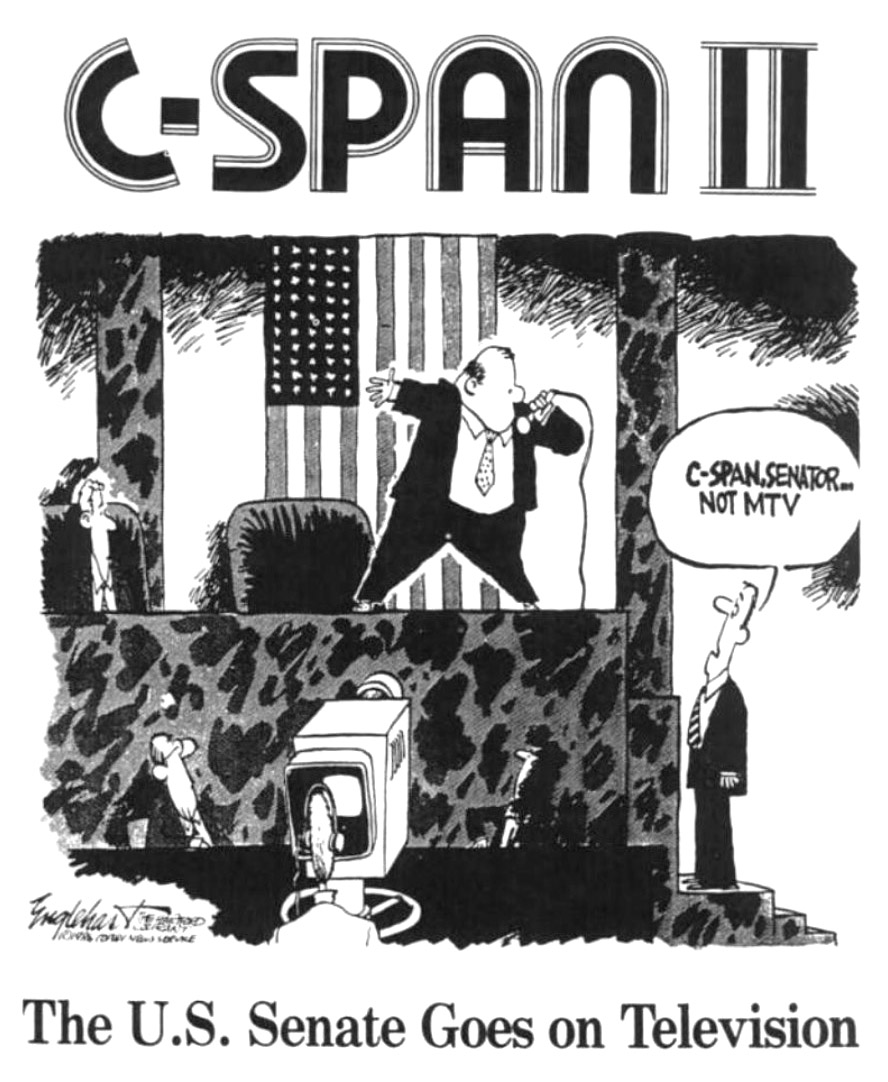

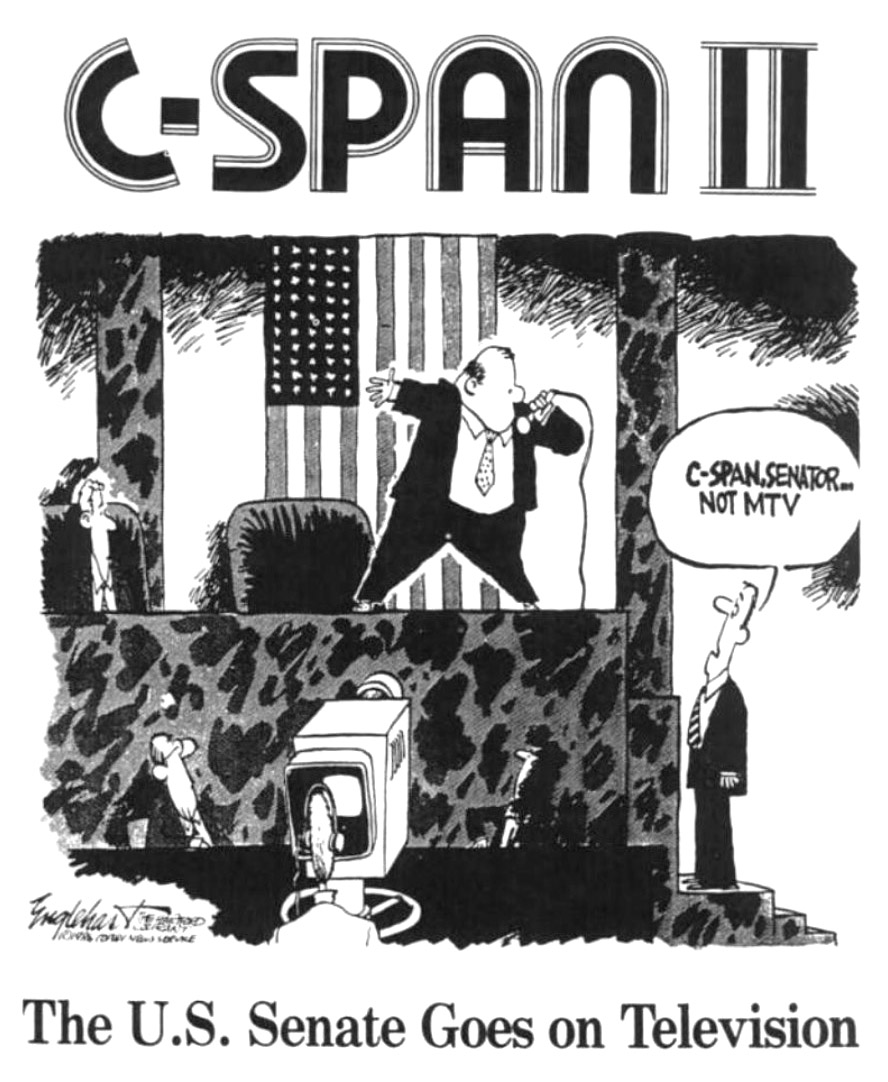

C-SPAN allows me to more effectively play the inside-the-beltway game.Lobbyist Ford West interviewed by Stephen Frantzich & John Sullivan 1996

The C-SPAN Revolution

Transparency in government causes the very corruption it aims to prevent, and the problem is universal.Michael Gilbert 2018

Transparency and Corruption

Open meetings give too much ammunition to single-issue interest groups.Sen. Judd Gregg (R.NH) 2011

Exposure vs. Efficiency

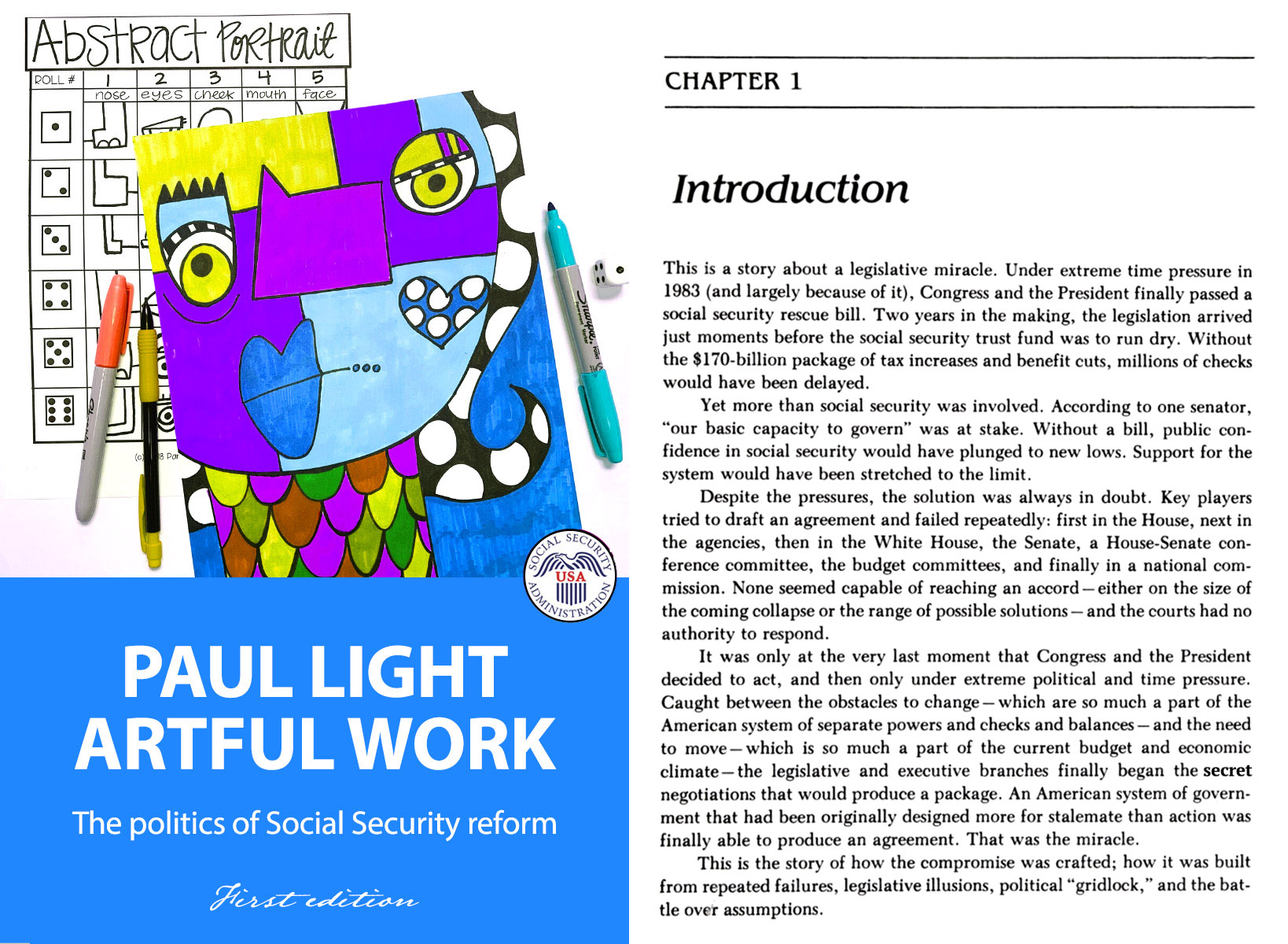

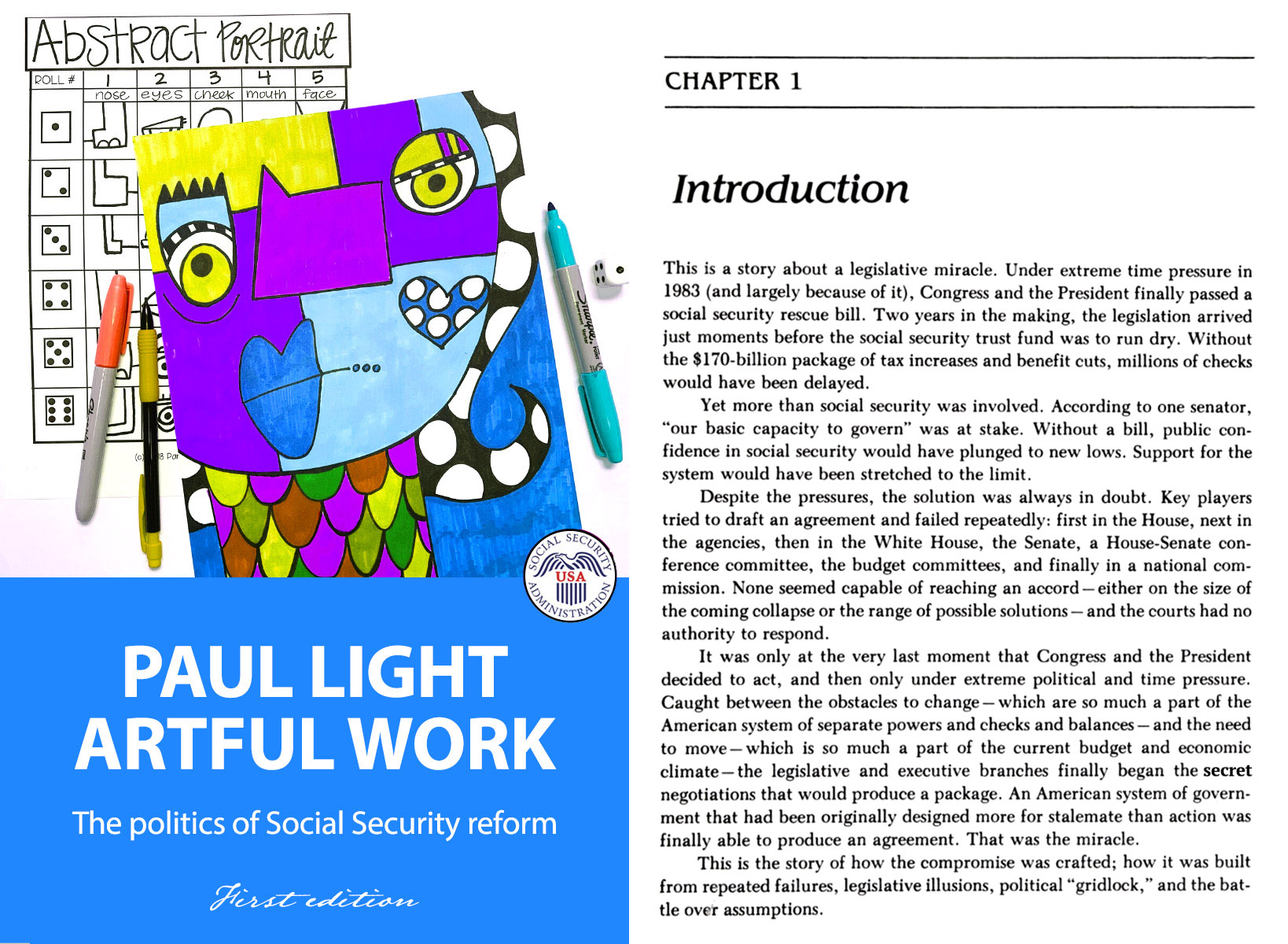

The sunshine was too intense for even the most responsible members.Paul Light 1985

Artful Work: The Politics of Social Security Reform p.22

James D'Angelo 2023 - Partisan support of Trump vs Johnson

James D'Angelo 2023 - Partisan support of Trump vs Johnson

Closed-door protection from media glare and lobbyist pressures allows legislators to trade public posturing for private deliberation.Cathie Jo Martin 2013

Conditions for Successful Negotiation

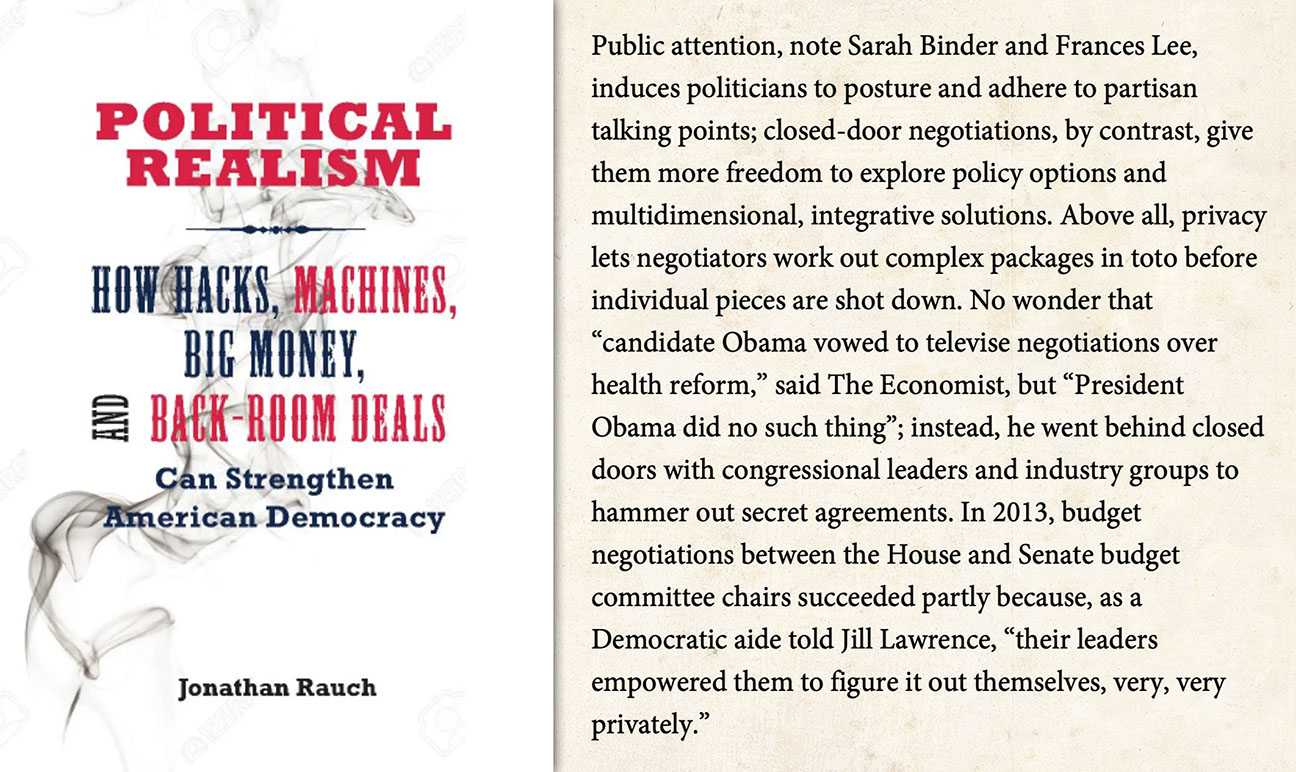

Transparency interferes with the search for solutions. Conducting negotiations of multidimensional, integrative solutions behind closed doors gives lawmakers more freedom to explore policy options.Sara Binder & Frances Lee 2013

Making Deals in Congress

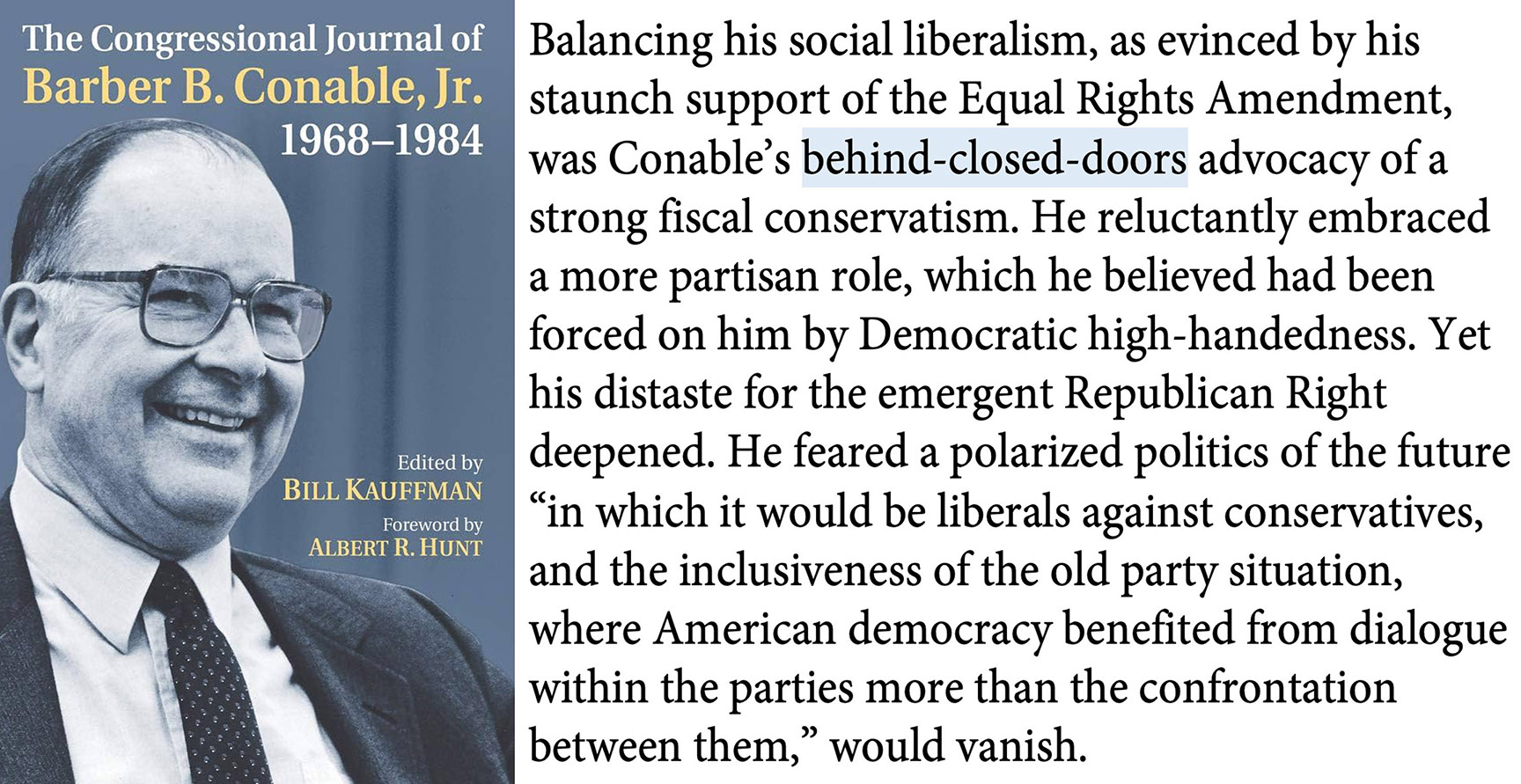

The sunshine laws played into the hands of the lobbyists who were in frequent attendance at committee meetings to keep an eye on the members.Barber B. Conable 2000

Window on Congress

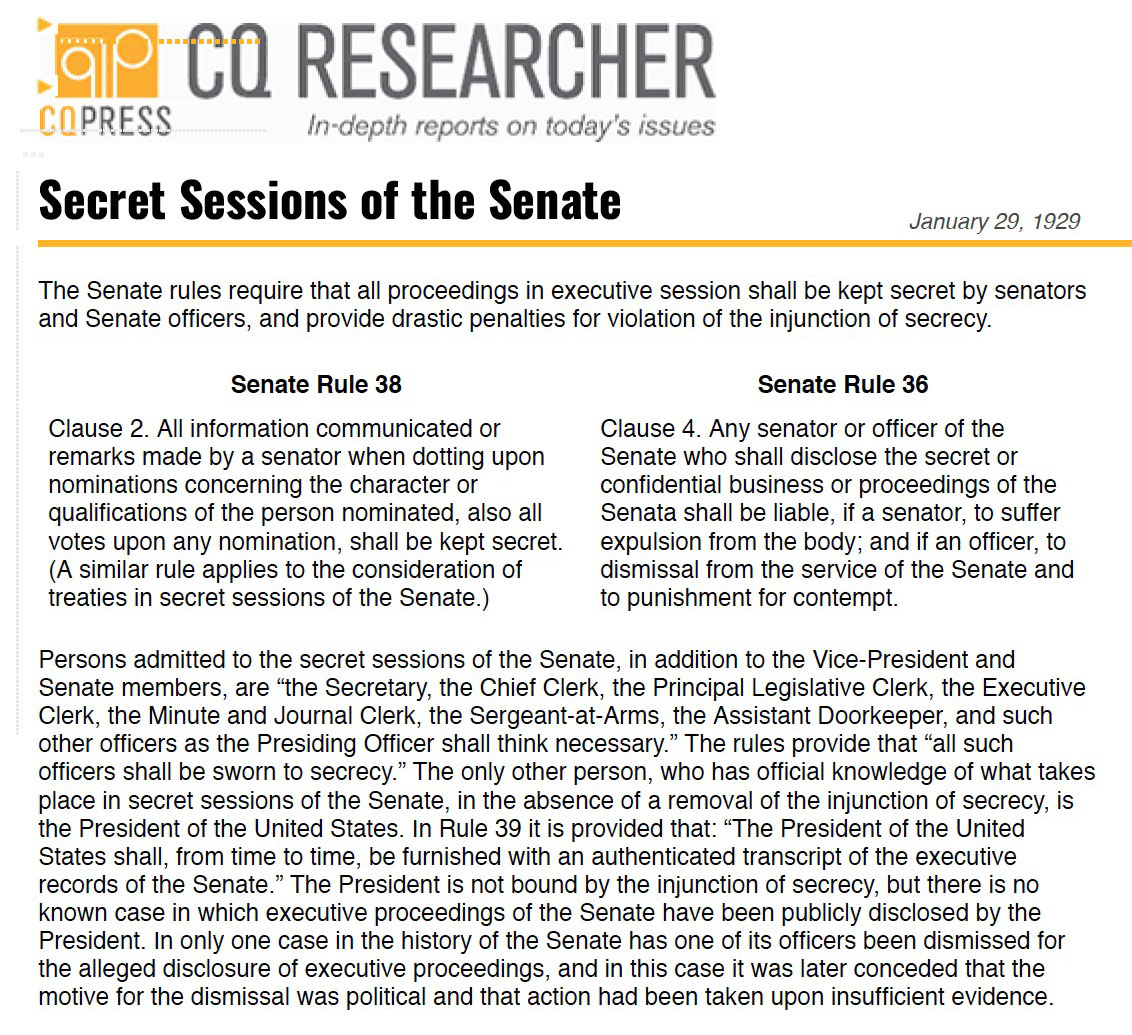

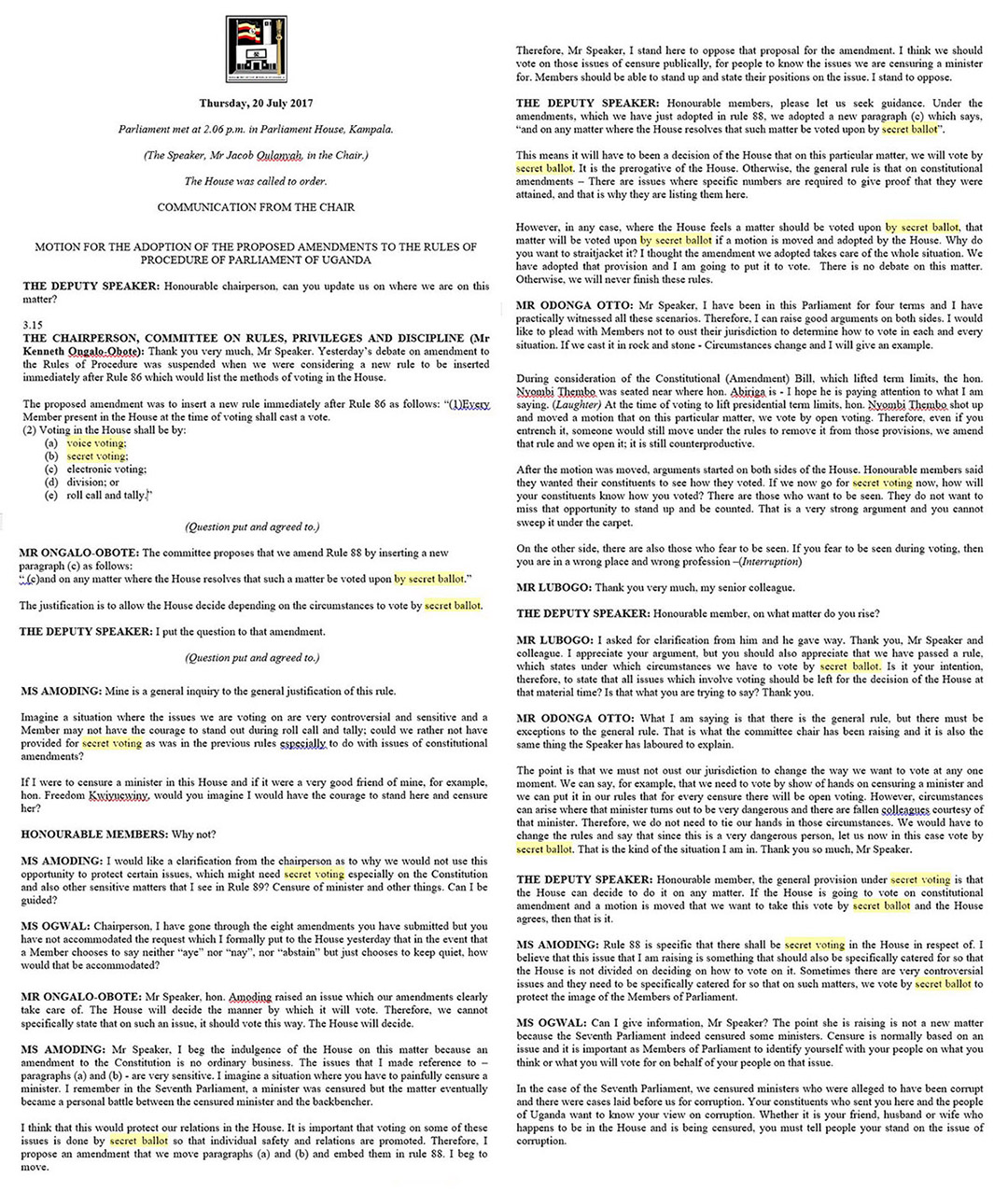

Congressional Quarterly 1929 - Secret Sessions of the Senate & Punishments for Transparency

Congressional Quarterly 1929 - Secret Sessions of the Senate & Punishments for Transparency

The Senate rules require that all proceedings in executive session shall be kept secret by senators and Senate officers, and provide drastic penalties for violation of the injunction of secrecy.Congressional Quarterly 1929

Secret Sessions of the Senate

America is increasingly embracing a simple-minded populism that values popularity and openness as the key measures of legitimacy. This ideology has necessitated the destruction of old institutions, the undermining of traditional authority, and the triumph of organized interest groups, all in the name of “the people.”Fareed Zakaria 2003

Future of Freedom

Citizens seem to prefer a government designed around less visible, less accountable actors.Kathryn VanderMolen 2017

Reconsidering Preferences for Less Visible Government

Paul Kane 2023 - Trump-backed hopefuls face tough foe in leadership races: Secret ballots

Paul Kane 2023 - Trump-backed hopefuls face tough foe in leadership races: Secret ballots

Transparency can undermine governance, even when well-intentioned.Richard M. Skinner 2019

Is Congress Broken?

Commitment to transparency allows interest groups capture where the democratic and regulatory process is constrained to prevent it. So, ideologically transparency claims make the negotiation seem more democratic when in fact they enable interest group across the Atlantic to capture the front end of the process.Fernanda Nicola 2015

The Paradox of Transparency

While most members of Congress and the public may be excluded from details of the private negotiations, so are lobbyists. That's a good thing, according to transparency watchdogs who say the involvement of lobbyists working on behalf of their narrow interests could make a deal impossible.Frank James (NPR) 2012

Open-Government Watchdogs OK With Closed-Door Fiscal Cliff Talks

Frank James NPR 2012 - Open Government Advocates OK with Secrecy

Frank James NPR 2012 - Open Government Advocates OK with Secrecy

From the interest group point of view, it is more beneficial to mobilize during open negotiations than to mobilize after secret (or open) negotiations. It follows then that interest groups will mobilize more often when negotiations are open.Barbara Koremenos 2010

Open Covenants, Clandestinely Arrived At

The beneficial effect of excluding the public from deliberation is...deliberation behind closed doors can proceed through a process of trial and error, through proposal and counterproposal, through persuasion and bargaining...This is impossible with pressure from the public, including that exerted by special interest groups.Anne Peters 2013

Towards Transparency as a Global Norm

Logrolling (vote trading in legislatures) leads to almost all projects being voted through, including those that have a net value to society that is negative. There can be so much logrolling (and so many bills passed) that even the “beneficiaries” of passed legislation (say, people in one state) may, on net, be worse off because of how much they have to pay in federal taxes to support the other legislation passed (that benefits other states).Deborah Walker 2020

Public Choice - Logrolling

But, neither is there any support in congressional action for the populist view that if people only knew, if procedure was only democratized and opened up, everything would come right. On the contrary, there are abundant signs that the reform mood can play into the hands of unprincipled demagogues. The House could go on a stampede any day for such dubious propositions as a tax cut or a ban on busing.Joseph Kraft 1971

Reform Mood In Congress

Transparency laws are so widespread and accepted in American governments that we rarely bother to actually assess their consequences. With impressive clarity and decisiveness, Harden and Kirkland find that these laws are actually making things worse, enabling organized interests to exert greater control over legislatures.Seth E. Masket 2022

The Illusion of Accountability: Transparency and Representation in American Legislatures

Lynne Cheney 2010 - We The People - The Story of Our Constitution

Lynne Cheney 2010 - We The People - The Story of Our Constitution

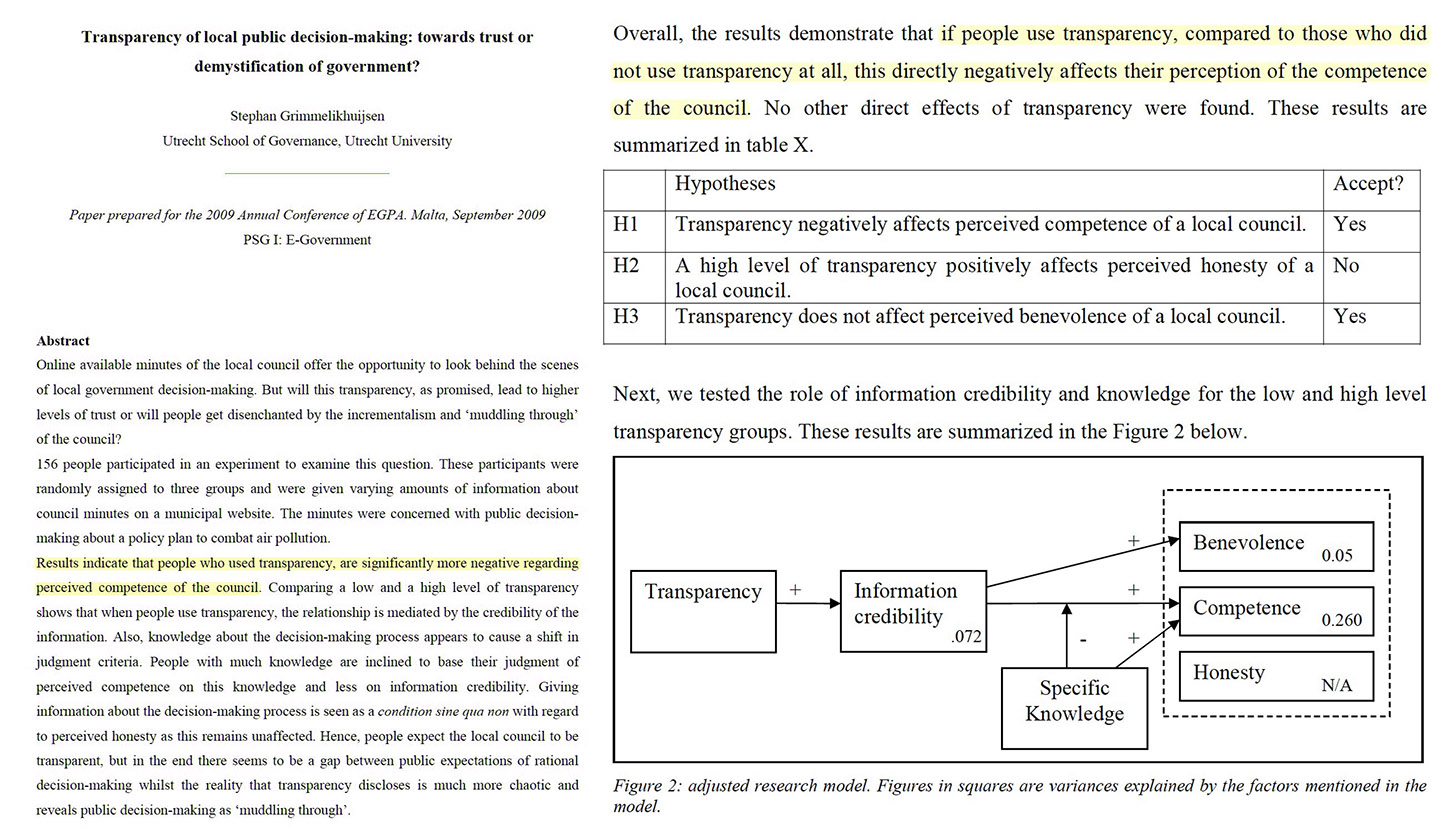

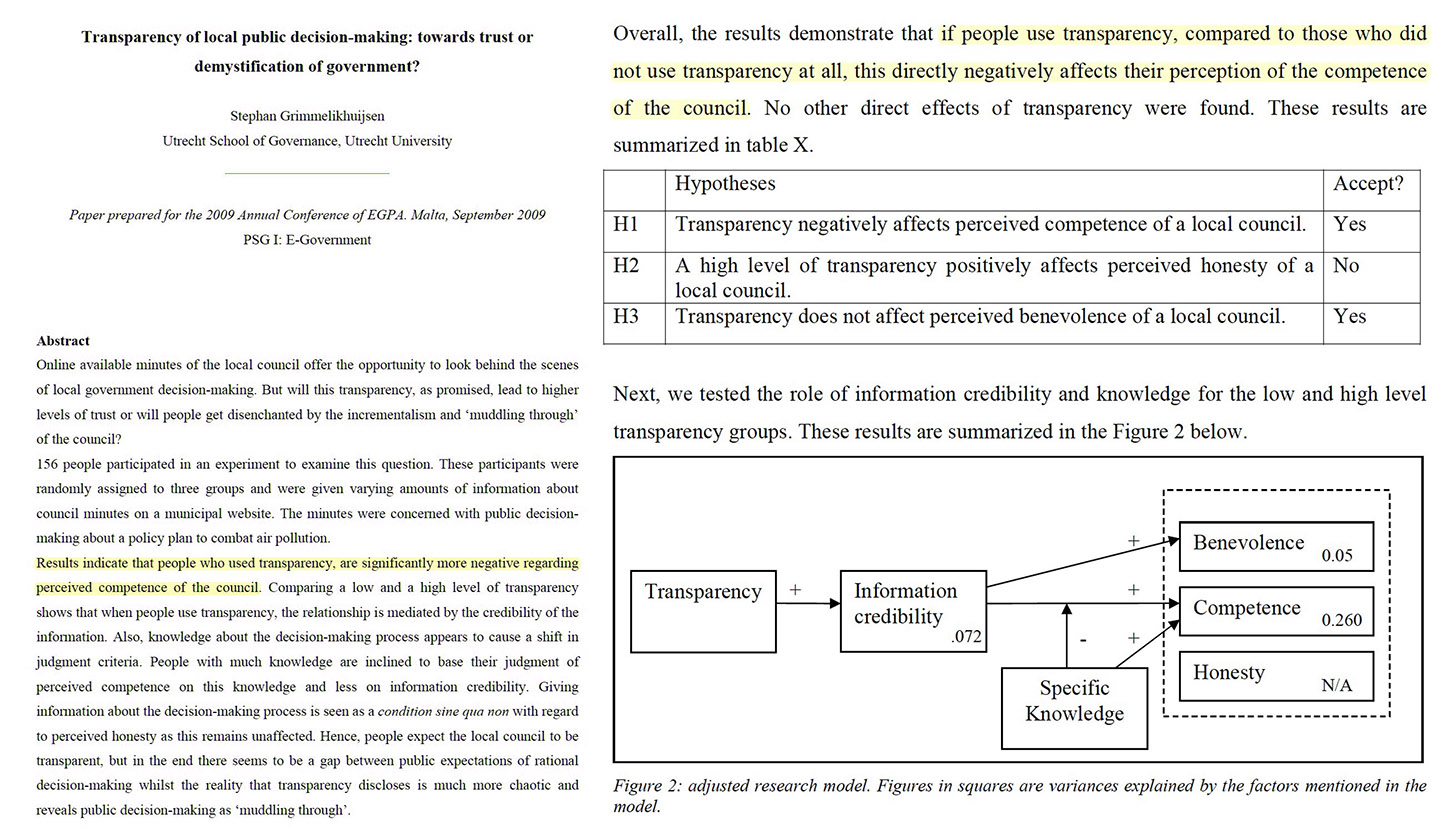

The results of this study hint at an insurmountable negative effect of transparency of public decision-making on citizens trust in a government organization. The decrease in perceived competence demonstrates that the dark side of transparency seems to prevail in this case, particularly the demystification of government behaviour. People notice that behind the scenes, public decision-making is not rational as it appears from the outside (Stone, 2000).Stephan Grimmelikhuijsen 2009

Transparency of local public decision-making

Does open governance strengthen democracy? The Illusion of Accountability contends that it does not. Leveraging a wealth of data from decades of legislative politics in the American states, the book assesses the causes and consequences of 'open meetings laws,' which require public access to proceedings in state legislatures. The work traces the roots of these laws back to the founding constitutions of some states and analyzes the waves of adoptions and exemptions to open meetings that occurred in the twentieth century. The book then examines the effects of these transparency laws on a host of politically consequential outcomes both inside and outside the legislature. This analysis consistently finds that open meetings do not influence legislators' behavior or citizens' capacity to alter that behavior. Instead, a link between transparent legislatures and an expanded system of organized interests is established. This illuminating work concludes that transparency reform only creates the illusion of accountability in state government.Justin H. Kirkland, Jeffrey J. Harden 2022

The Illusion of Accountability: Transparency and Representation in American Legislatures

[One of the first results of the open voting in 1971 was a special interest coup. It] was passage of the $250 million guarantee to Lockheed, by a mere three votes a near miracle considering that the administration, the banks, labor and a lot of industry wanted the bill while the Democratic leaders were concerned to protect their party from a charge that they had defeated the bill and thus contributed to unemployment… Moreover, the House has passed 10 out of 14 major appropriations bills which is far In advance of the usual pace. The serious question, accordingly, is not the quantity of legislation. The serious question is how open politics affects the quality of congressional action.Joseph Kraft 1971

Reform Mood In Congress

The Freedom of Information Act is the Taj Mahal of the Doctrine of Unanticipated Consequences, the Sistine Chapel of Cost-Benefit Analysis Ignored.Anton Scalia 1982

The Freedom Of Information Has No Clothes (FOIA, Executive)

Sarah Binder 2015 - Downsides of Transparency (Order in the House)

“Would we have seen the emergence of these restrictive rules even without the rules changed in the 1970s? Perhaps… But I think much of what we see in the House today, the roots lie in these reforms of the 70s, which obviously were originally in the pursuit of greater transparency and greater accountability.”

Sarah Binder 2015 - Downsides of Transparency (Order in the House)

While political parties can in principle moderate the effects of interest group politics, it is also true that political parties have sometimes supported reforms that make them more vulnerable to interest groups, such as the “sunshine laws” adopted in the reform atmosphere of the 1970s.Kenneth W. Dam 2001

The Rules of the Global Game

Although there may be benefits to “sunshine laws” and other measures to make negotiations open, our results show that they may actually harm efficiency. For this reason, sometimes negotiations should be kept secret.Tim Groseclose & Nolan McCarty 2001

The Politics of Blame - Bargaining Before an Audience

A close look at the Philadelphia Convention thus reveals several desirable features of secret deliberation. First, secret deliberation facilitates compromise by allowing participants to change their views. Second, secret deliberation mollifies partisan fervor. And third, secret deliberation allows for exploratory and thorough debate. Such insights perhaps suggest that more of our democratic deliberation ought to occur behind closed doors. This conclusion is too quick, for it neglects the potential costs of secret deliberation. Brian Kogelmann 2021

Secret Government: The Pathologies of Publicity

Take the banking lobby, for example, one that a lot of lawmakers can depict as a dark influence without fear of retribution by the voters. Wright Patman, the chairman of the House Banking Committee, has a rueful memory of the time two years ago when he tested the theory that open sessions would help defeat the big banks he forever fights.

Rep. Patman was pushing a bill that the big banks opposed, and he figured an audience would demonstrate to other committee members that the people were on his side. Indeed, the committee was influenced by the audience. It voted against Mr. Patman and for the bill the bank lobbyists wanted. “We got some press, but most of the seats in the room were filled by (bank) lobbyists obviously interested in pushing through the softest possible bill,” Mr. Patman recalls. “The members of the committee were looking down the throats of at least $100 billion in bank assets...”Norman C. Miller 1971

Here is a Reform We Do Not NeedNote: Worth noting that lobbyists likely learned from these sunshine experiments as well. And, as Jaqueline Clames wrote in 1987, the lobbyists and banks became some of the strongest proponents for open meetings.

It is considered a breach of good faith for members to disclose what went on in the committee while in executive session, even though they may be sorely tempted to do so; and the votes taken in committee are never made a matter of public record. It is easy to condemn (as some have done) the secrecy surrounding committee deliberations. But there is another side to the matter. In the executive sessions of committees, writes an experienced member already quoted, falls “the most interesting, important, and useful part of the work of a congressman, and the part, of which the public knows nothing. Indeed, the ignorance of the public about it is one of the causes of its usefulness. Behind closed doors nobody can talk to the galleries or the newspaper reporters. Buncombe is not worthwhile. Only sincerity counts.”Robert Luce 1926

Congress: An Explanation

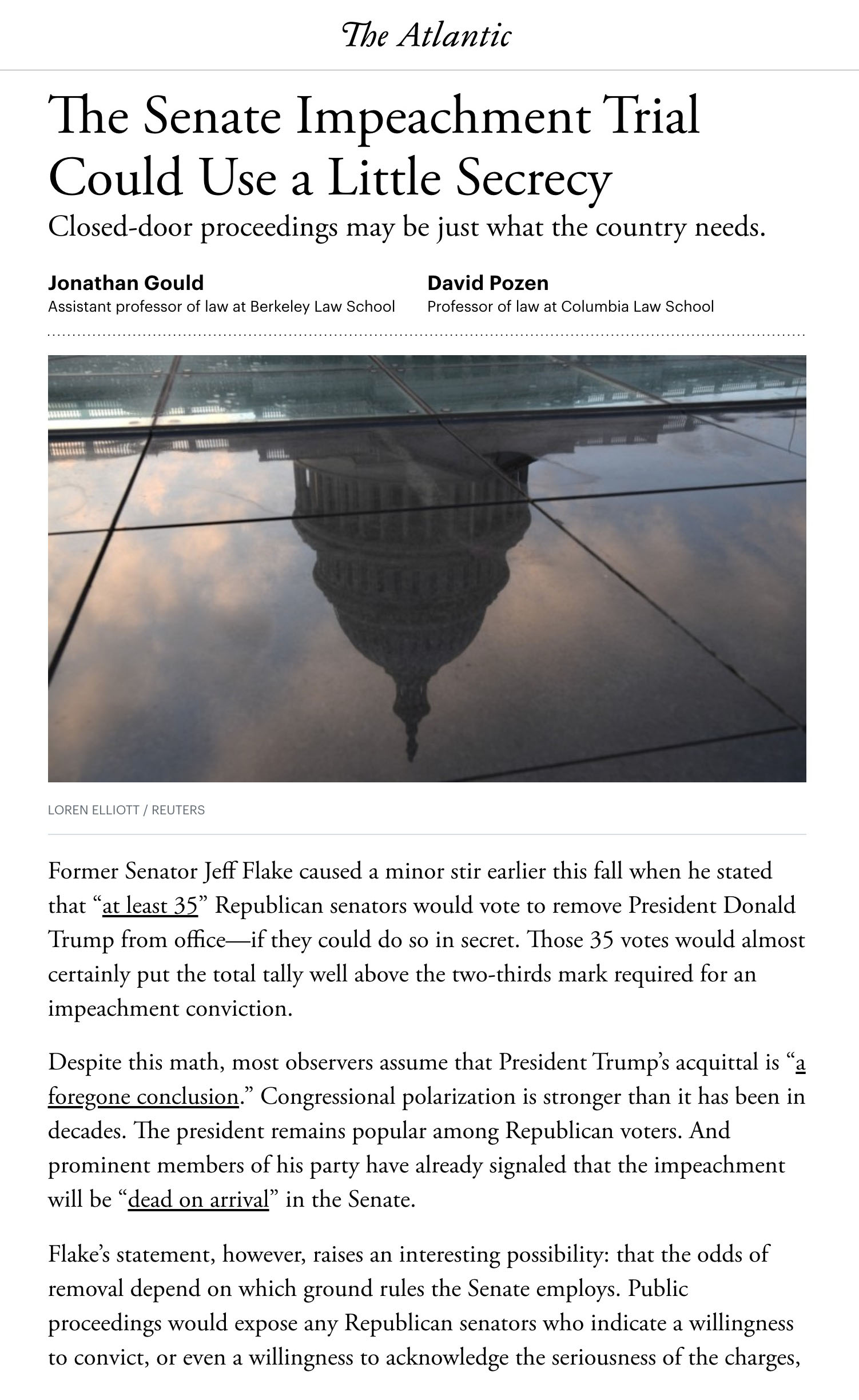

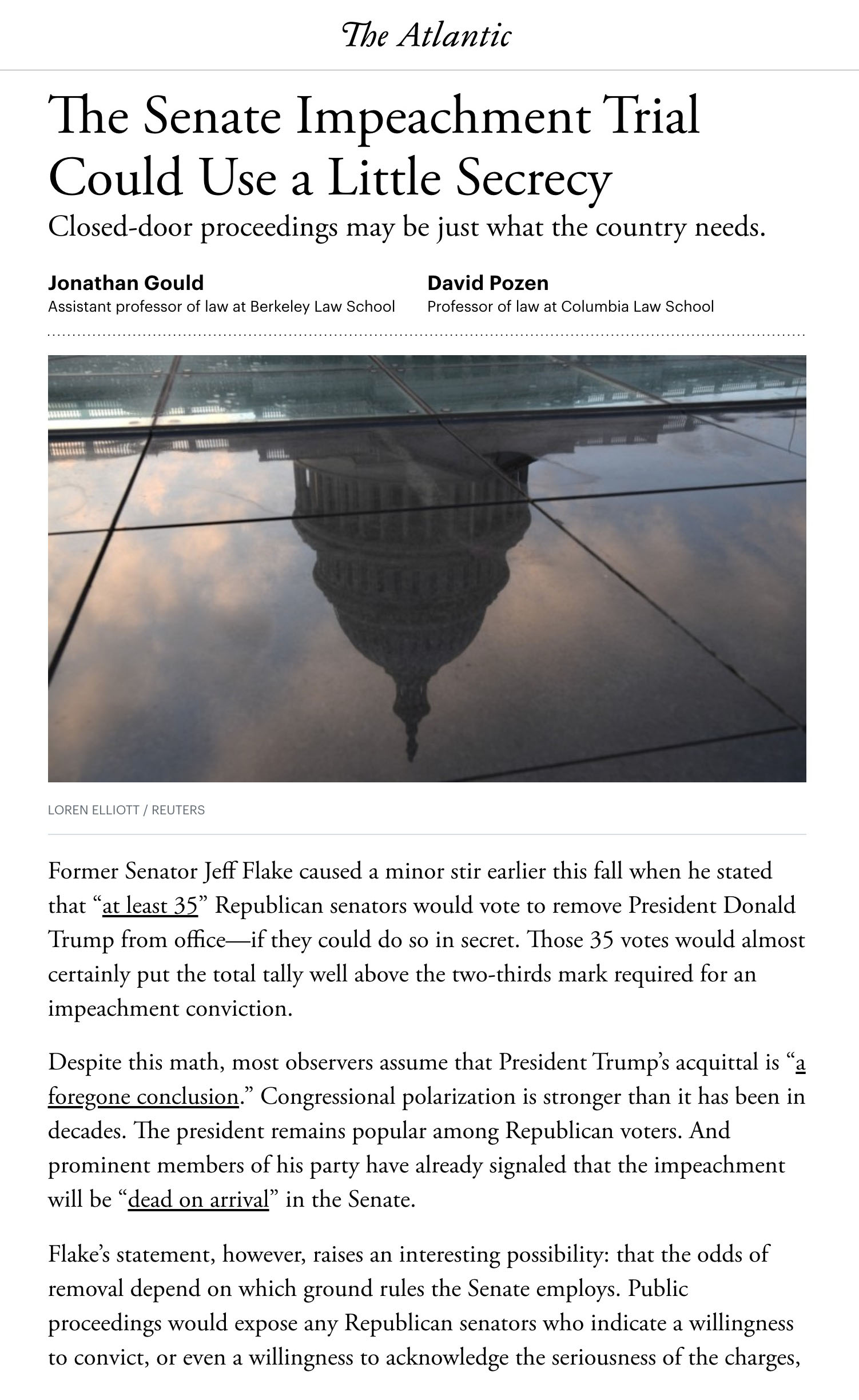

Senators said the closed doors, combined with the inability of senators to posture for the cameras or the news media, led to more free-flowing and elevated discussion as lawmakers expressed their views without fear of retaliation — or today’s equivalent of a social media beatdown. Joseph I. Lieberman, a former Democratic senator from Connecticut, said he remembered such debates in 1999 as some of the most meaningful of his time in the Senate.Carl Hulse 2020

NY Times – Impeachment Out Of Public View

In a world of closed meetings, interest groups must rely on second-hand accounts and often cannot be sure what negotiations had occurred. Furthermore, because most interest group bargains in the budget context are not obviously corrupt, and many are low salience bargains that voters will overlook even if they are made in the open, the threat of disclosure may not appreciably reduce the level of private-regarding behavior. Thus, transparency may empower interest groups and their lobbyists in one realm without substantially harming them in another.Elizabeth Garrett & Adrian Vermeule 2006

Transparency in the Budget Process

Steve Tidrick 1999 - Senate Should Vote in Secret

Steve Tidrick 1999 - Senate Should Vote in Secret

Transparency helps promote oversight by voters or constituents, and thus promotes the accountability of representatives to voters or constituents. Yet it also promotes oversight or monitoring by third parties – narrow interest groups, self-interested officials elsewhere in government, and others. Adrian Vermeule (Harvard Law) 2007

Mechanisms of Democracy

Some of the people who are screaming about transparency the loudest are the most ridiculous. They have never believed in transparency a previous day in their lives. They’re only advocating something they believe will scuttle a deal.Melanie Sloan 2012 (CREW - Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington)

Open-Government Watchdogs OK With Closed-Door Fiscal Cliff Talks

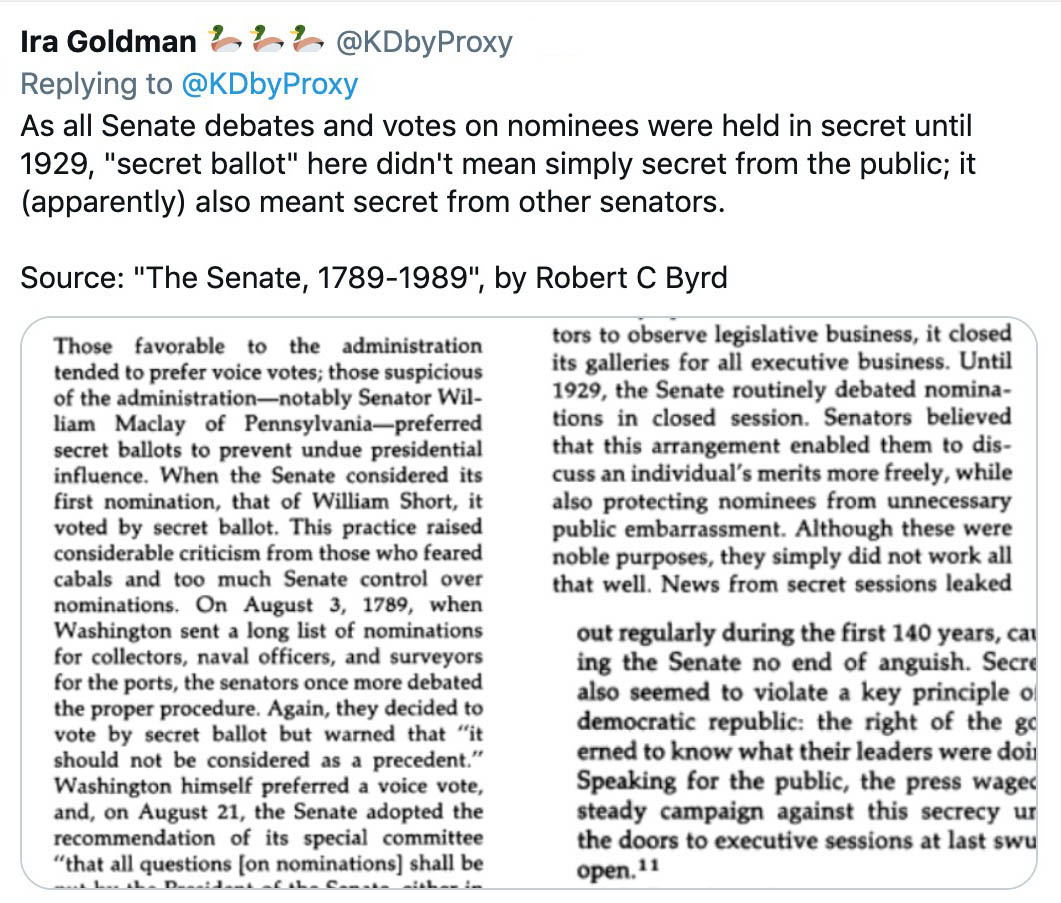

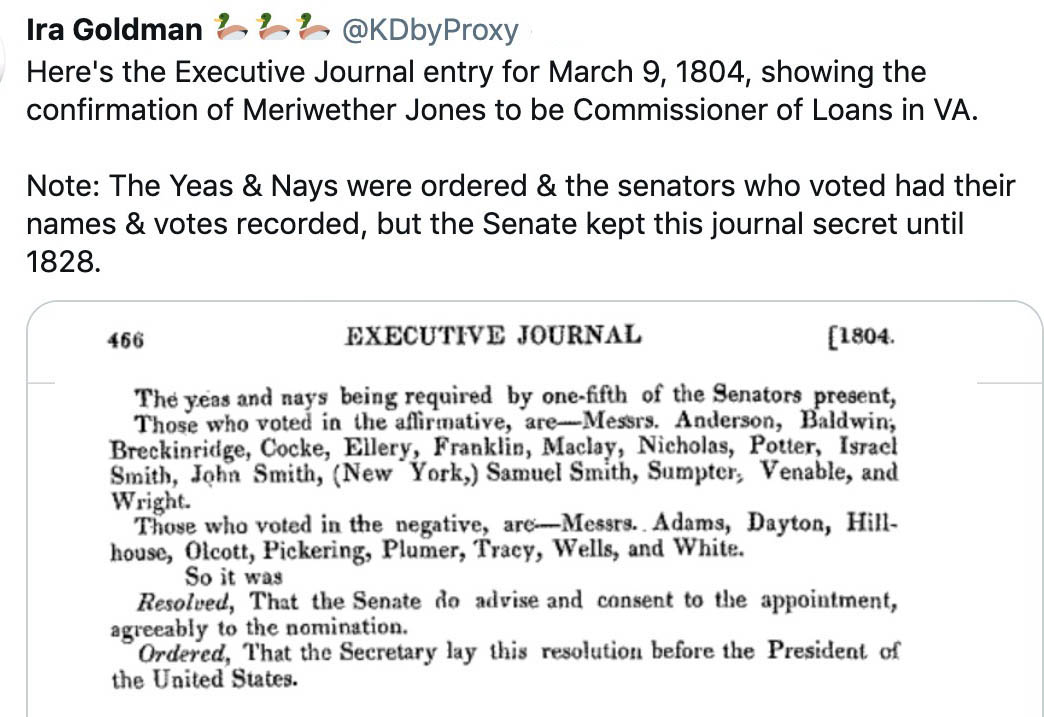

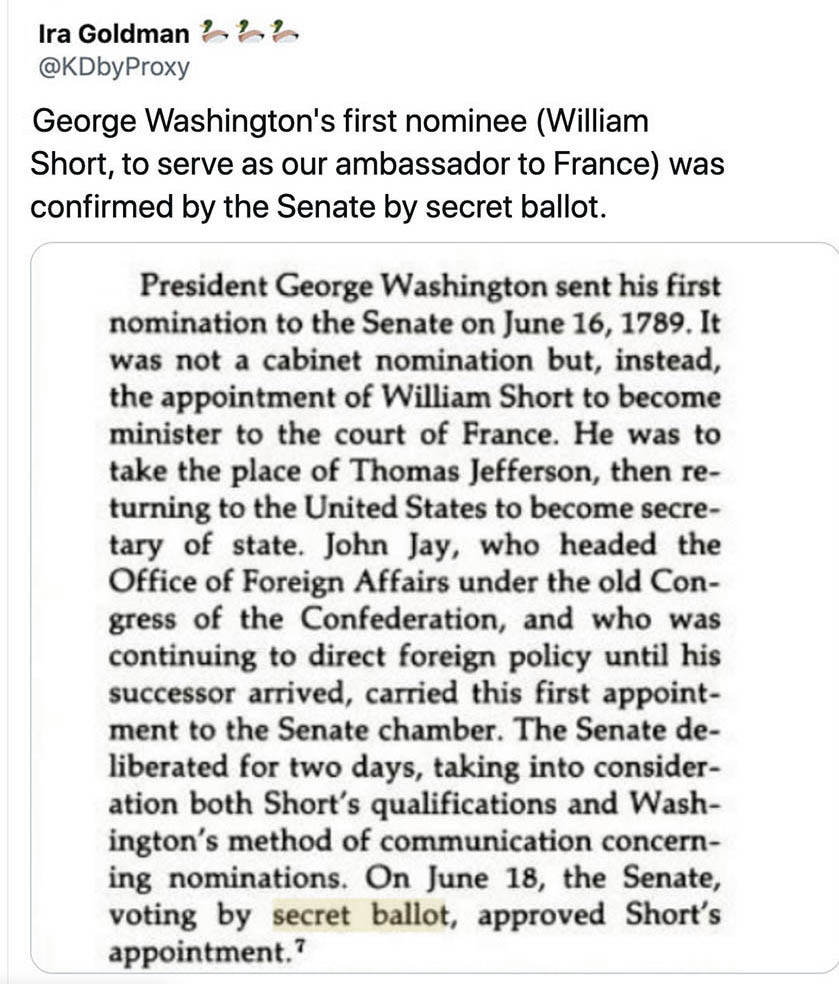

All treaties and nominations [in Congress] continued to be debated in secret until the twentieth century... [And] a fickle press showed little interest in the Senate’s open sessions.Donald Ritchie 1991

Press Gallery: Congress and the Washington CorrespondentsNote: According to author Ritchie, the very newspapers that were so furious about secrecy failed to show up to observe Congress when the doors were opened. The galleries remain to this day mostly empty with a scattering of lobbyists.

Justin H. Kirkland, Jeffrey J. Harden 2022 - The Illusion of Accountability - Transparency and Representation in American Legislatures

Justin H. Kirkland, Jeffrey J. Harden 2022 - The Illusion of Accountability - Transparency and Representation in American Legislatures

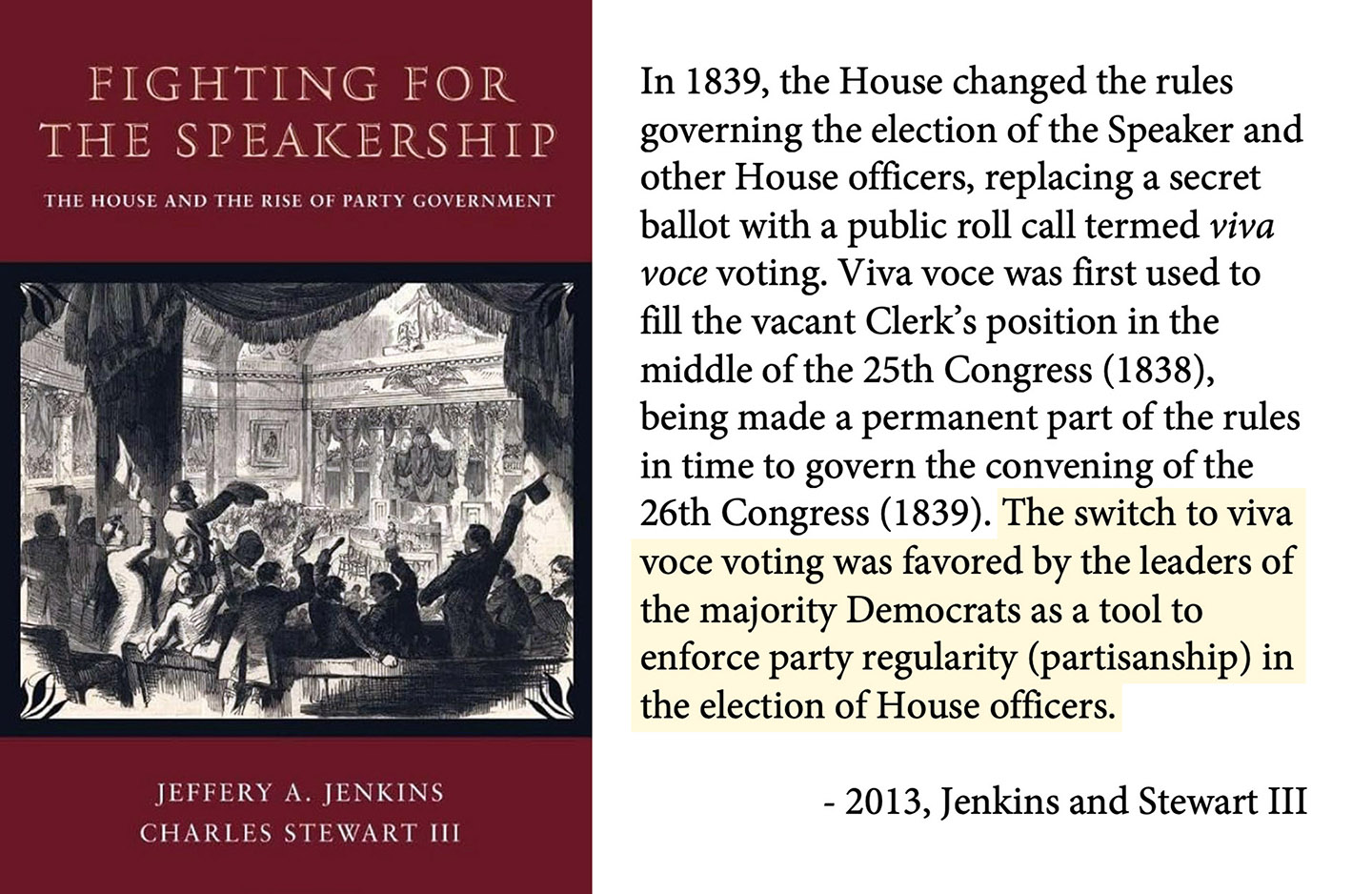

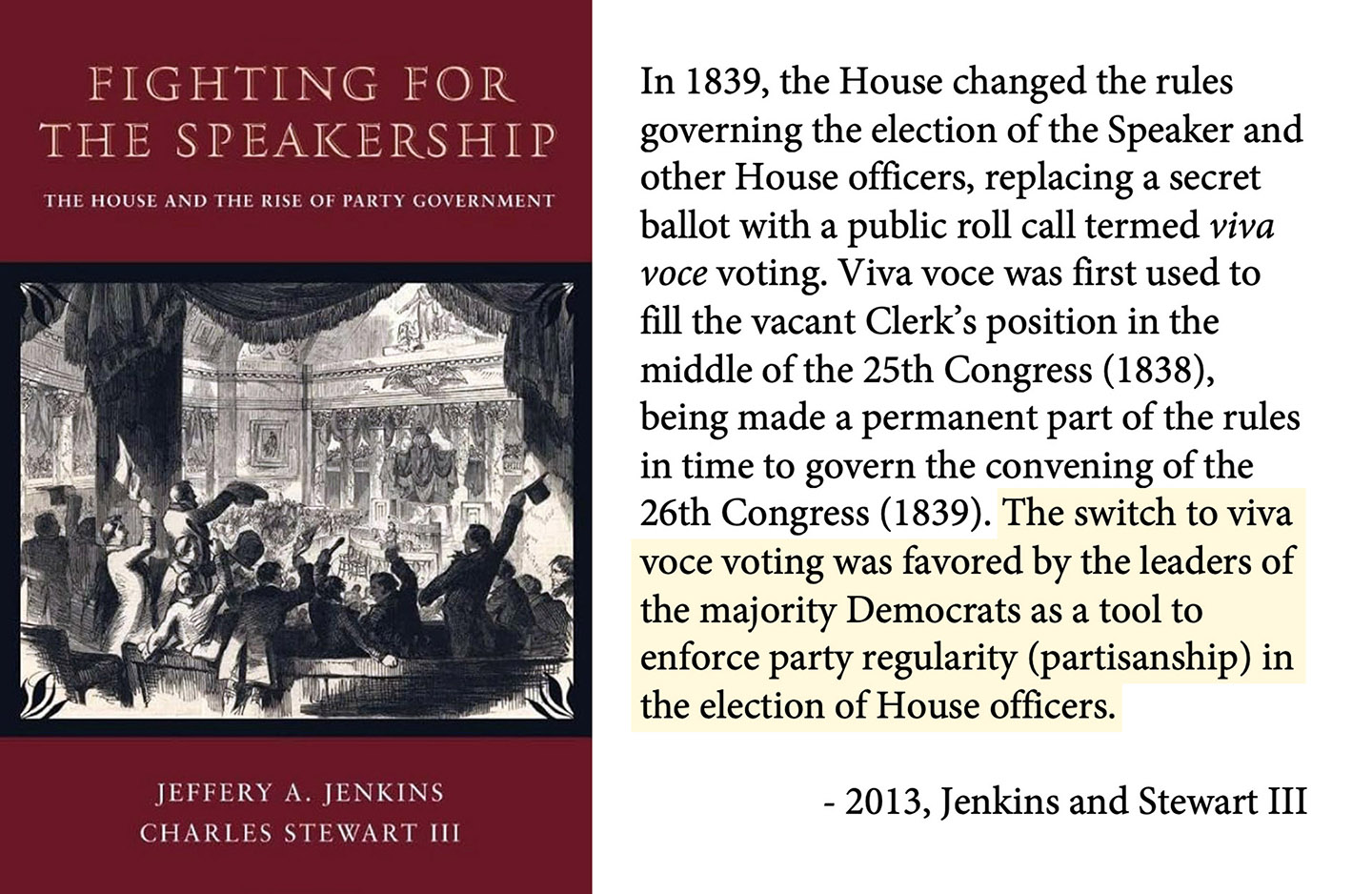

As occurs so often in the course of American reform movements, light is presented as the solution to corruption which occurs in secret and in darkness: light is the great disinfectant. But of course what that reasoning applied to this circumstance meant was that every individual vote would be an even more visible, even more a public declaration for any interested observer to see, just as any observer at a viva voce election could hear every vote. Transparency, not secrecy, was the solution to the ills of American politics. It would take another generation for the opposite view to take hold: that the solution to the ills of American politics was secrecy, not visibility and not transparency, but voting as a private act and a ballot box that shielded every vote from scrutiny.Donald A. Debats 2016

Voting Viva Voce - Unlocking the Social Logic of Past Politics

While Congress is sometimes viewed by the public as an enemy, we wish to call attention to the fact that it is often viewed as an enemy because it is so public. John Hibbing & Elizabeth Thiess-Morse 1995

Congress as Public Enemy (trust)

By now [James] Madison also understood that reticence had its political uses. It was wise to avoid strong statements while circumstances were still unfolding. It was often advantageous to put forth proposals anonymously and thus avoid alienating allies who might not agree. If in avoiding center stage Madison missed some of the praise, he also avoided some of the criticism, thus saving his reputation for a future day… It might have been during the extra time he spent at Princeton that Madison took notes in a commonplace book that survives today. It shows him interested in secrets, which would be natural at a period in his life when he probably wanted as few people as possible to know what had happened to him. Reading the Memoirs of Cardinal de Retz, he stopped to copy this passage: “Secrecy is not so rare among persons used to great affairs as is believed.” He added his own thought, “Secrets that are discovered make a noise, but these that are kept are silent.” De Retz’s Machiavellian insights interested him (“To lessen envy is the greatest of all secrets”), as did de Retz’s description of a rising churchman who did not reveal much of himself, Cardinal Fabio Chigi, who, wrote de Retz, “was not very communicative, but in the little conversation he had he showed himself more reserved and wise (savio col silentio) than any man I ever knew.” Reflecting on the sentence, Madison offered his own, more pointed version: “He showed his wisdom by saying nothing.”Lynne Cheney 2014

James Madison - A Life Considered

We must recognize that there are moments in government where the imperative for deliberation trumps the imperative for access.Jason Grumet 2014

When sunshine doesn’t always disinfect the government

Throughout American history, whenever we’ve been faced with a deeply entrenched internal divide, the solution has nearly always been forged within a certain zone of confidentiality.Jason Grumet 2014

The Dark Side of Sunlight (City of Rivals)

Most of the tough issues were solved around small tables, over dinner at night, or in the Cloak Room between votes. Often when there was an important disagreement, I would gather the key senators into my conference room and tell them not to leave until they figured it out. Sometimes it took a few sessions, but an agreement usually emerged.Bob Dole 2014

City of Rivals

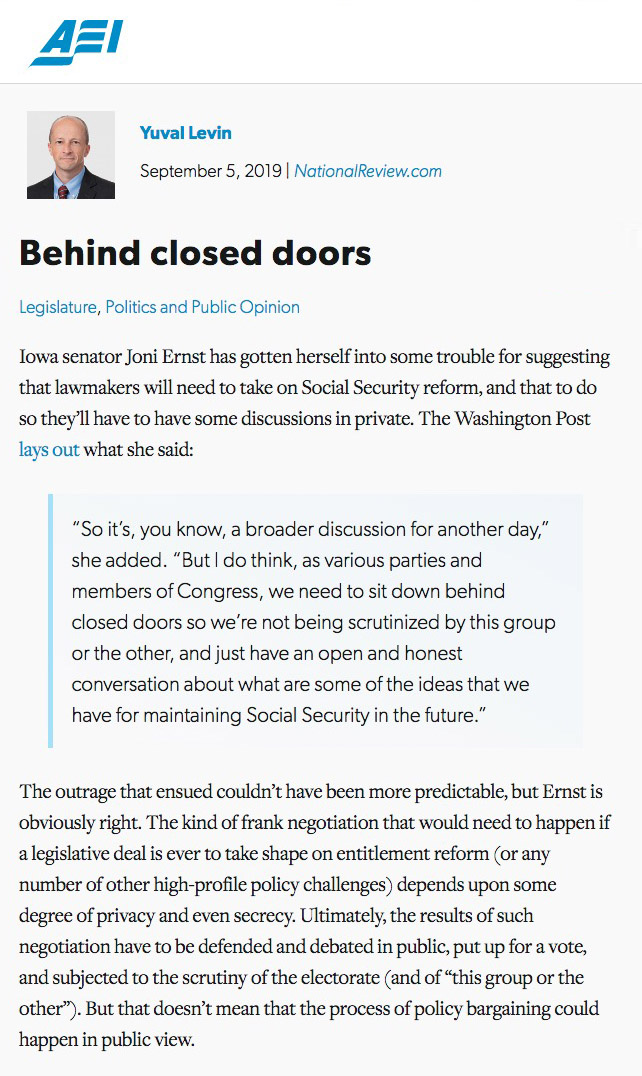

There has to be some balance struck between privacy for the sake of bargaining and transparency for the sake of accountability. But we have gone much too far in the direction of transparency, so that our core deliberative institutions have become so transparent as to essentially lack an interior altogether.Yuval Levin 2019

Behind Closed Doors

Beth Reinhard 2023 - DeSantis wanted to ban guns but not be blamed

Beth Reinhard 2023 - DeSantis wanted to ban guns but not be blamed

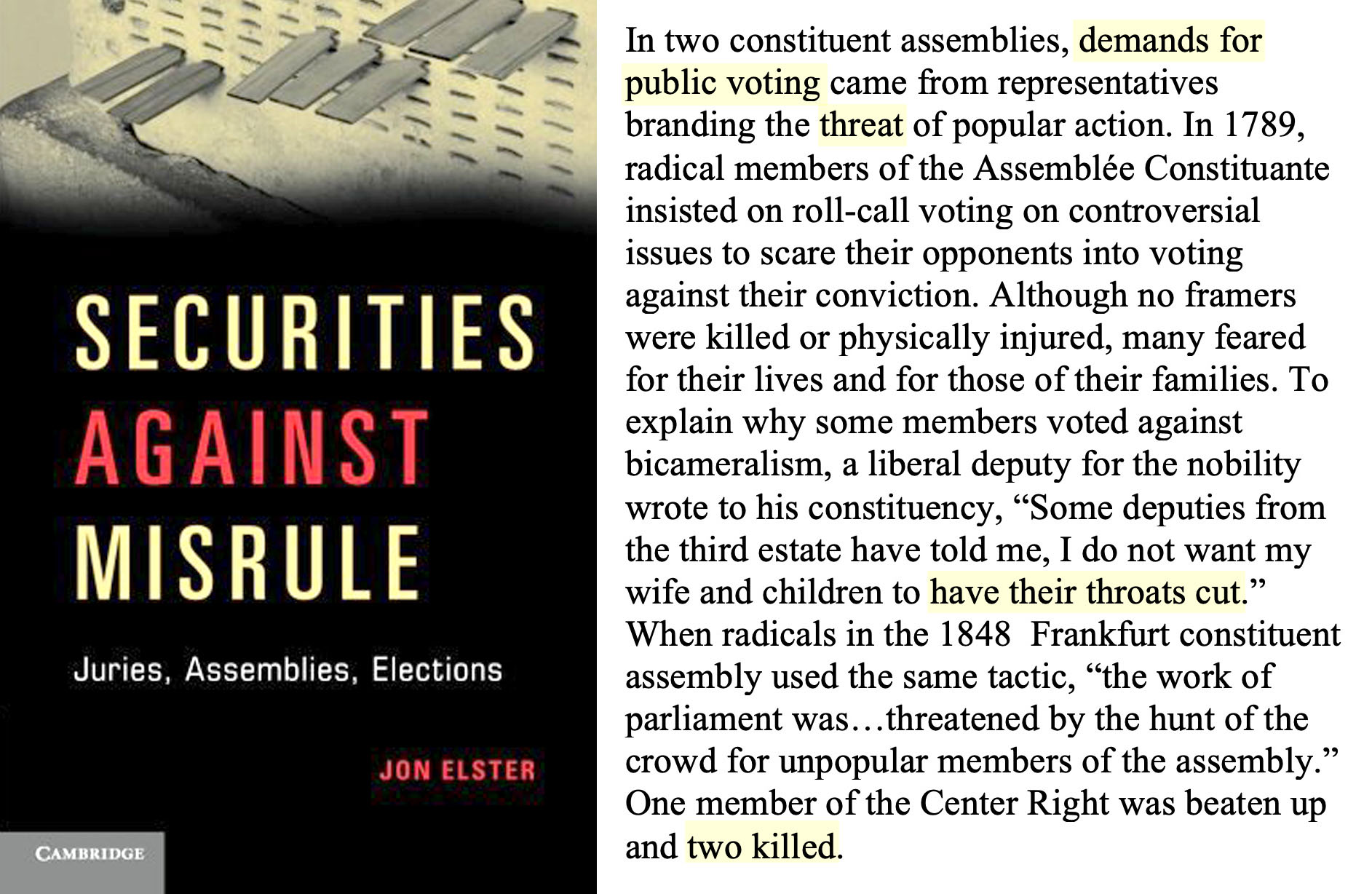

As a final example, I shall cite the argument made by James D’Angelo that the combination of public voting in Congress and huge private contributions to election campaigns has undermined American democracy, by enabling lobbyists to verify that a representative they have funded votes the way they want.Jon Elster 2015

Secrecy and Publicity

The fragmented power game, fostered by the [1970s reforms], played into the hands of lobbies. It not only helped AIPAC block President Reagan on Arab arms deals, but the more open power game enabled the bank lobby to resist a tax law backed by the president and leaders of both houses of Congress, by stimulating such a popular groundswell that congressional members turned against their political leaders. The parties used to provide the most essential organization, money, and endorsement that politicians needed. Parties and their leaders weighed the competing demands of interest groups, sorted out priorities, struck compromises and then provided what politicians call “cover” for the votes of individual Congress members: taking the political heat for unpopular votes and delivering bad news to groups that were not satisfied.Hedrick Smith 1988

The Power Game - How Washington Works

Writing in 1929, in terms foreshadowing today's literature, [Pendleton] Herring pointed to changes in Congress that invigorated group activity and altered the scope and methods of lobbying. In particular, he cited the reform of rules of procedure in the House of Representatives in 1911 that broke up the power center and distributed control more generally in the House; he also pointed to the adoption, at about the same time, of open congressional committee hearings as being a spur to group activity (Herring, 1929, pp. 41-43). Kay Lehman Schlozman & John T. Tierney 1983

More of the Same: Pressure Group Activity

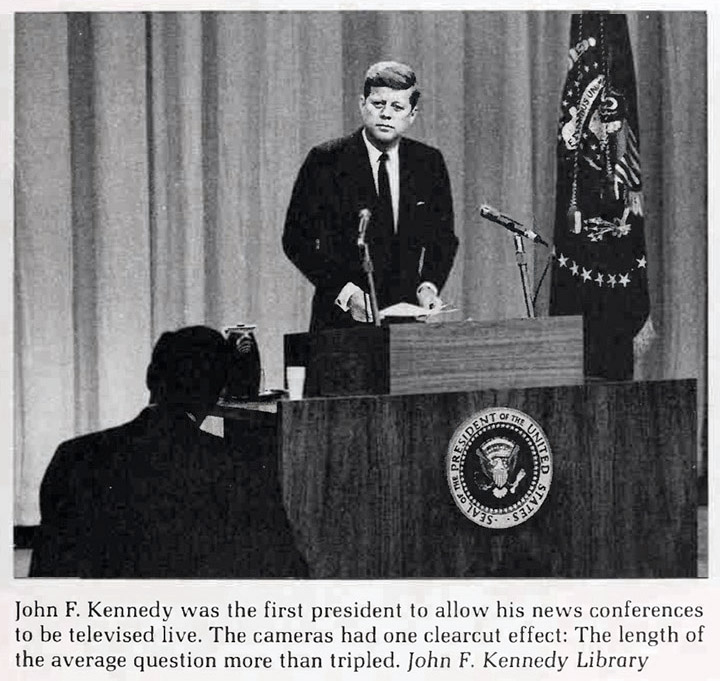

John Boehner 2012 - Leadership Enforces Partisanship by Watching Votes and Punishing Members

Text: Speaker John Boehner (R-Ohio) warned his conference on Wednesday that leaders are “watching” how the rank-and-file vote to determine committee assignments, according to sources in the closed-door meeting. Boehner addressed the firestorm over the removal of four lawmakers from plum committee assignments at the weekly GOP conference meeting. According to Rep. Tim Huelskamp (R-Kan.), one of the lawmakers denied a spot on his current committee in the next Congress, Boehner did note “that we [leadership] have punished four members, he claimed that it had nothing to do with their conservative ideology, but had to do with their voting patterns.” Also removed from committee spots were Reps. Justin Amash (R-Mich.), Walter Jones (R-N.C.) and David Schweikert (Ariz.). Huelskamp added that Boehner warned GOP lawmakers that “there may be more folks that will be targeted … ‘we’re watching all your votes.”

John Boehner 2012 - Leadership Enforces Partisanship by Watching Votes and Punishing Members

Indeed, in the days when Appropriations committees saw their mission as cutting spending rather than maximizing it, appropriators carried out virtually all of their activities, including hearings, behind closed doors… William Natcher, D-Ky., closed his markups after taking over the Labor-HHS Subcommittee in 1979, arguing that it would be too difficult to put together a fiscally responsible bill if special interests could record how every member voted on every amendment. The temptation to vote yes on everything would be too great.George Hager 1991

Behind Closed Doors (CQ Magazine)

You will not find it in political science textbooks, but it is nonetheless an immutable truth that, before an audience of reporters [when the committees are open to the public], politicians just can’t shut up. Somehow, even a Congressman whose every utterance is religiously ignored feels compelled to talk endlessly as long as a single soul sits suffering at the press table.Norman C. Miller 1971

Here is a Reform We Do Not Need

Yet, transparency has a dark side that, ironically, has everything to do with a lack of mystery, shadow, and nuance. Behind the apparent accessibility of knowledge lies the disappearance of privacy, homogenization, and the collapse of trust. The anxiety to accumulate ever more information does not necessarily produce more knowledge or faith. Technology creates the illusion of total containment and the constant monitoring of information, but what we lack is adequate interpretation of the information. In this manifesto, Byung-Chul Han denounces transparency as a false ideal, the strongest and most pernicious of our contemporary mythologies.Byung-Chul Han 2012

The Transparency Society

Those who pay closest attention to markup sessions are lobbyists who use the occasion to press for changes the serve their interests.Joseph Bessette & John Pitney 2011

American Government and Politics

If you judge the committee’s work by the bottom line, they have a pretty good case for closing. It’s hard to close loopholes when there are lobbyists in the room.Robert S. McIntyre 1983

Citizens for Tax Justice

Congress would likely find it quite difficult to craft and enact priority legislation absent private meetings and discussions.Walter Oleszek 2011

Congressional Lawmaking: A Perspective On Secrecy and Transparency

The Paris outcome was made possible by the heavy use of secrecy. The agreement is a composite mélange of building block pieces, many of which were negotiated in secret over the two weeks and preceding months. Secrecy is common in diplomacy, but the French finessed it to a new level – and with compelling efficacy.Radoslav S. Dimitrov 2016

The Paris Agreement on Climate Change: Behind Closed Doors

Senator Howell Heflin 1986 - A Sonnet on Transparency

Turn the spotlight over here.

Focus the camera at my place.

Pages, please don’t come near,

Otherwise, you just might block my face.

Some have made the worst claim yet,

That viewers will tire from the dull plot,

But I’ll be willing to make a bet

Lobbyists will watch a whole lot.

Senator Howell Heflin 1986 - A Sonnet on Transparency

Focus the camera at my place.

Pages, please don’t come near,

Otherwise, you just might block my face.

Some have made the worst claim yet,

That viewers will tire from the dull plot,

But I’ll be willing to make a bet

Lobbyists will watch a whole lot.

We argue that making lawmakers more accountable to the public by making it easier to identify their policy choices can have negative consequences… Lawmakers who would do the right thing behind close doors may no longer do so when policy is determined in the open.Justin Fox 2006

Government Transparency and Policymaking

Lawmakers desiring more closed committee work sessions do not lack variety in their criticism of the new openness: more partisan behavior, too much political speechifying, unusually blatant lobbying, temptation to refrain from discussing radical alternatives.CQ Quarterly 1976

Should congressional work sessions be open to public?

Keeping an accurate vote count is one of the hardest but most important aspects of a congressional legislative fight.Jack Abramoff 2011

Capitol PunishmentNote: Abramoff, one of the most infamous lobbyists talks about how knowing the vote totals (because they are public and countable) is essential.

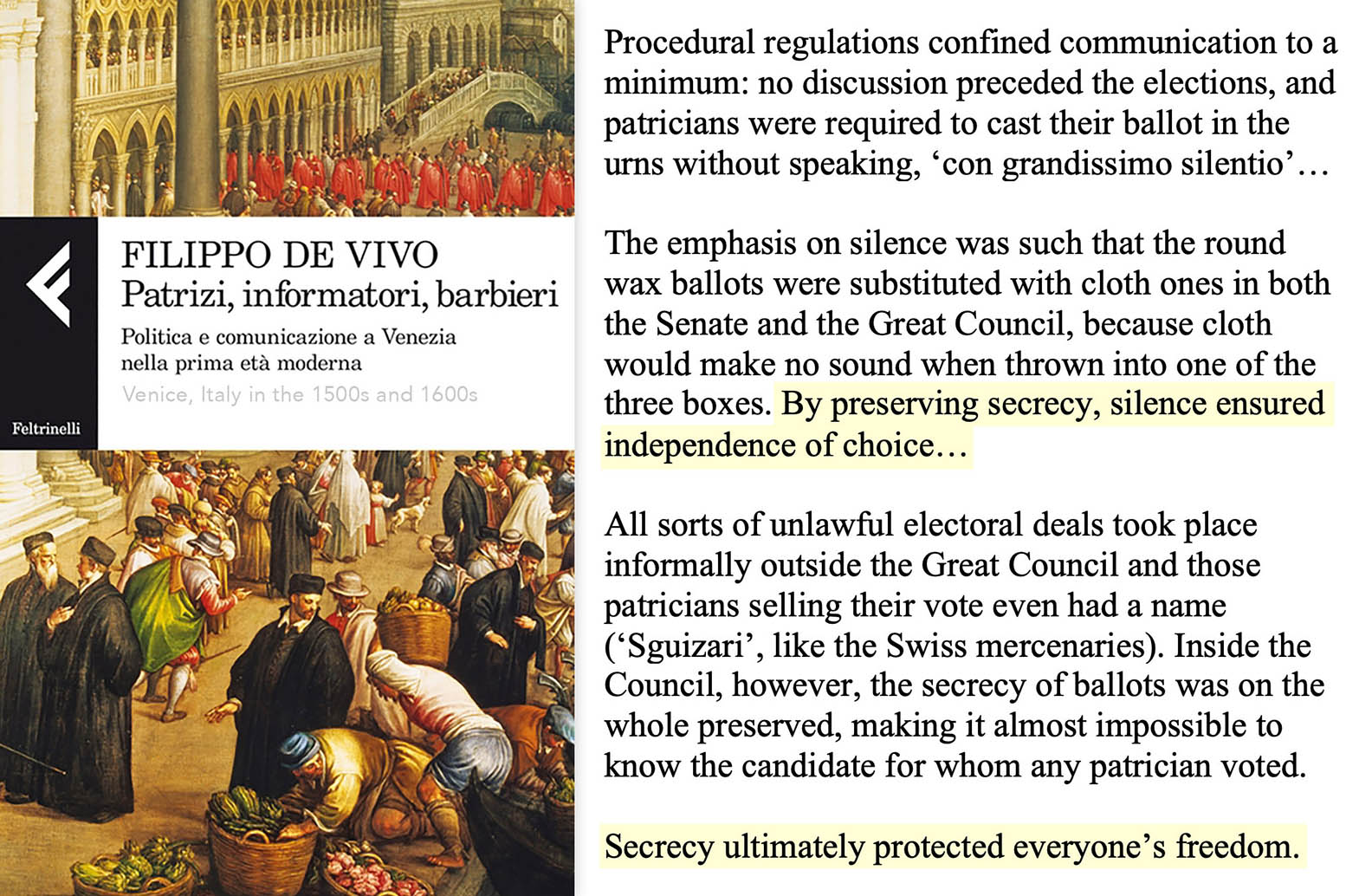

De Vivo 2007 - Information and Communication in Venice

Procedural regulations confined communication to a minimum: no discussion preceded the elections, and patricians were required to cast their ballot in the urns without speaking, ‘con grandissimo silentio’…The emphasis on silence was such that the round wax ballots were substituted with cloth ones in both the Senate and the Great Council, because cloth would make no sound when thrown into one of the three boxes. By preserving secrecy, silence ensured independence of choice…All sorts of unlawful electoral deals took place informally outside the Great Council and those patricians selling their vote even had a name (‘Sguizari’, like the Swiss mercenaries). Inside the Council, however, the secrecy of ballots was on the whole preserved, making it almost impossible to know the candidate for whom any patrician voted. Secrecy ultimately protected everyone’s freedom. (Patrizi, informatori, barbieri)

De Vivo 2007 - Information and Communication in Venice

Even transparency deserves a critical look. Hill rags and Internet gossip sheets now cover incremental legislative updates, with a focus on process, which is ugly and easily distorted for partisan gain. Leaked comments and proposed deals often stymie negotiators.Alex Seitz-Wald 2013

Washington’s Bad Old Days Worked Better Than the Good New Ones

Open negotiations are akin to allowing interest groups to add amendments.Barbara Koremenos 2010

Open Covenants, Clandestinely Arrived At

Voters are the subject of every kind of mass appeal and mass flattery by those who want their votes. In such circumstances, the inflexibility which open negotiation encourages is apt to harden into complete rigidity.Lester B. Pearson 1955

Democracy in World Politics

Some of the sunshine reforms of the 1970s had the unintended consequence of strengthening the role of special interests.Walter Oleszek 2011

Congressional Lawmaking: A Perspective On Secrecy and Transparency

The 1970 Clean Air Act was smooth, easy and important. It was mostly hashed out in secret, too.Michael Wines 1994 (NY Times Climate)

Who can govern while all those phones, faxes and focus groups are yelling?

We wouldn’t have had 150 amendments to the energy bill if the lobbyists hadn’t been in there – we’d only have had 10 or 15.Rep Harley Staggers (D-WV) 1973

Government in the Sunshine

Rachael Doyle 2017 - The Founding Fathers Encrypted Secret Messages, Too

Text: Thomas Jefferson is known for a lot of things — but his place as the “Father of American Cryptography” is not one of them. While serving as the third president of the newly formed United States, he tried to institute an impossibly difficult cipher for communications about the Louisiana Purchase. He even designed an intricate mechanical system for coding text that was more than a century ahead of its time. Cryptography was no parlor game for the idle classes, but a serious business for revolutionary-era statesmen who, like today’s politicians and spies, needed to conduct their business using secure messaging. Going into the Revolution, Americans were at a huge disadvantage to the European powers when it came to cryptography, many of which had been using “black chambers”—secret offices where sensitive letters were opened and deciphered by public officials—for centuries. The Founding Fathers continued to rely on encryption throughout their careers: George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, John Jay, and James Madison all made ample use of codes and ciphers to keep their communiqués from falling into the wrong hands.

Rachael Doyle 2017 - The Founding Fathers Encrypted Secret Messages, Too

At a public session, NPR found that plenty of lobbyists were lined up for seats. The reason for the great interest is a little surprising. One lobbyist explained “There’s an obsession with intelligence gathering-whether it’s right or wrong-that’s what clients want.” These limitations were made clear when lobbyist Gerald Cassidy told the same publication: “During my 42 years in Washington, this is the most closed-mouth committee that I’ve seen.” If they were hard pressed to find information about the Super Committee’s legislation, it seems unlikely that they would have been able to score any special deals or advance any untoward interests… It seems secrecy could have allowed the panel to produce a good bill.Mark Strand and Timothy Lang 2011

The Super Secret Committee

But people close to the process say the velocity of the soundbite culture on Capitol Hill has forced the real action to go behind the scenes, where controversial ideas can be floated, discussed, and digested without becoming the target practice for pundits on cable news and, in turn, outside groups looking out for their interests.Patricia Murphy 2011

Congressional Secrecy

Barbara Sinclair 2017 - Unorthodox Lawmaking - Voice Votes on Clean Air Act 1970

Note: Sinclair looks at how secrecy allowed for the straightforward passage of climate legislation in 1970. In comparison to today, the 1970s worked on legislation in closed committees with secret votes, today they are both open, driving hardlining and partisanship. To date, all effective climate legislation has benefit from important levels of secrecy. In other citiations on this page (and in her seminal book), she remarks how secrecy prevents capture by lobbyists and diminishes partisanship.

Barbara Sinclair 2017 - Unorthodox Lawmaking - Voice Votes on Clean Air Act 1970

“It’s easier to bully politicians than to bully voters” Jim Kessler replies. Recalling that the Manchin-Toomey bill to expand background checks got 55 votes in the senate but fell short of the 60 needed to overcome a filibuster, he says, “If there were a secret ballot in Congress, these gun laws would pass. But there isn’t, and the NRA takes retribution.” Eleanor Clift 2014

NRA Ducks Gun Fight Out West

Probably when you close the doors in the Chamber of the House and the TVs go off, these guys are actually sitting down and being professionals and trying to get things done.Dr. John Cowan 2021