The Legislative

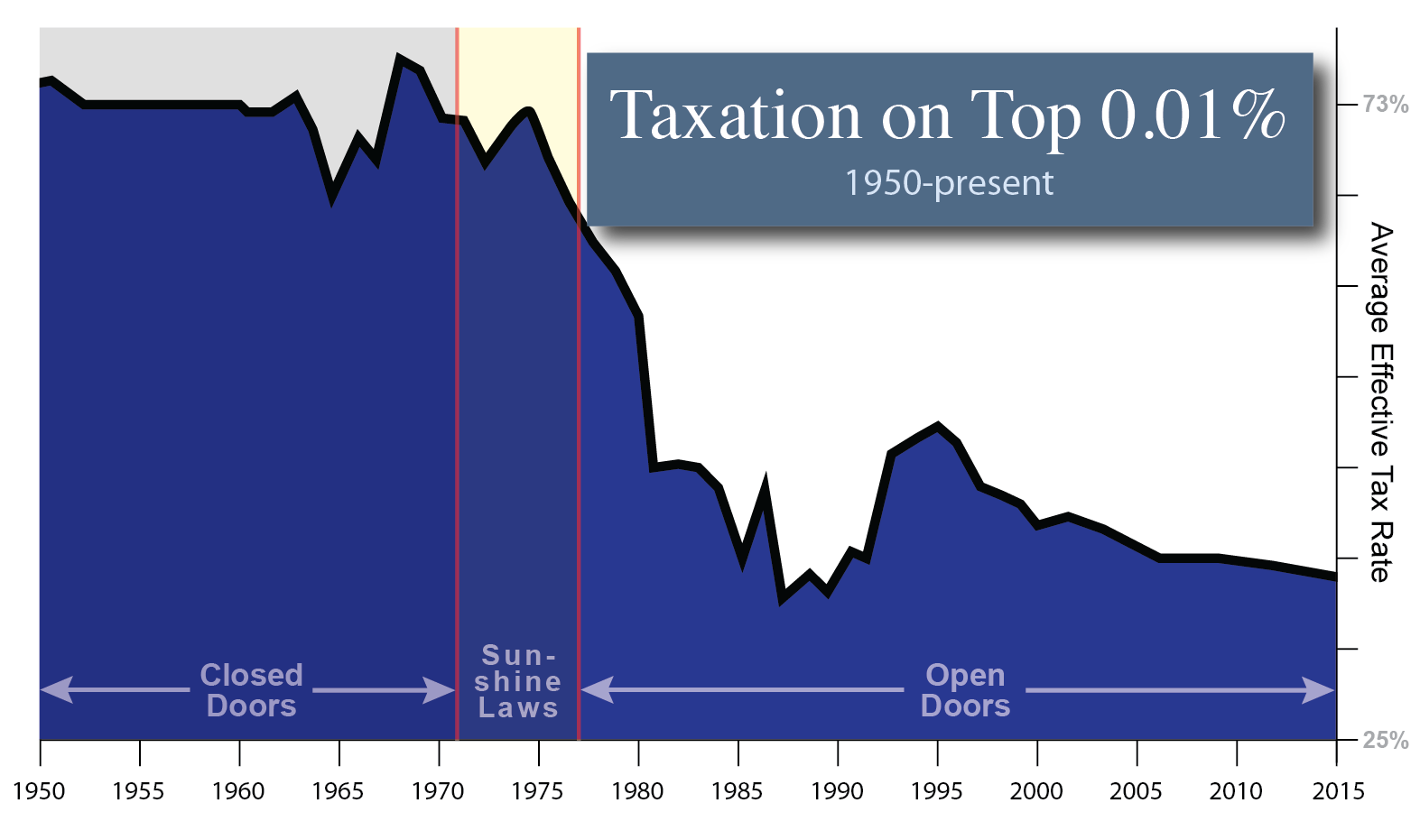

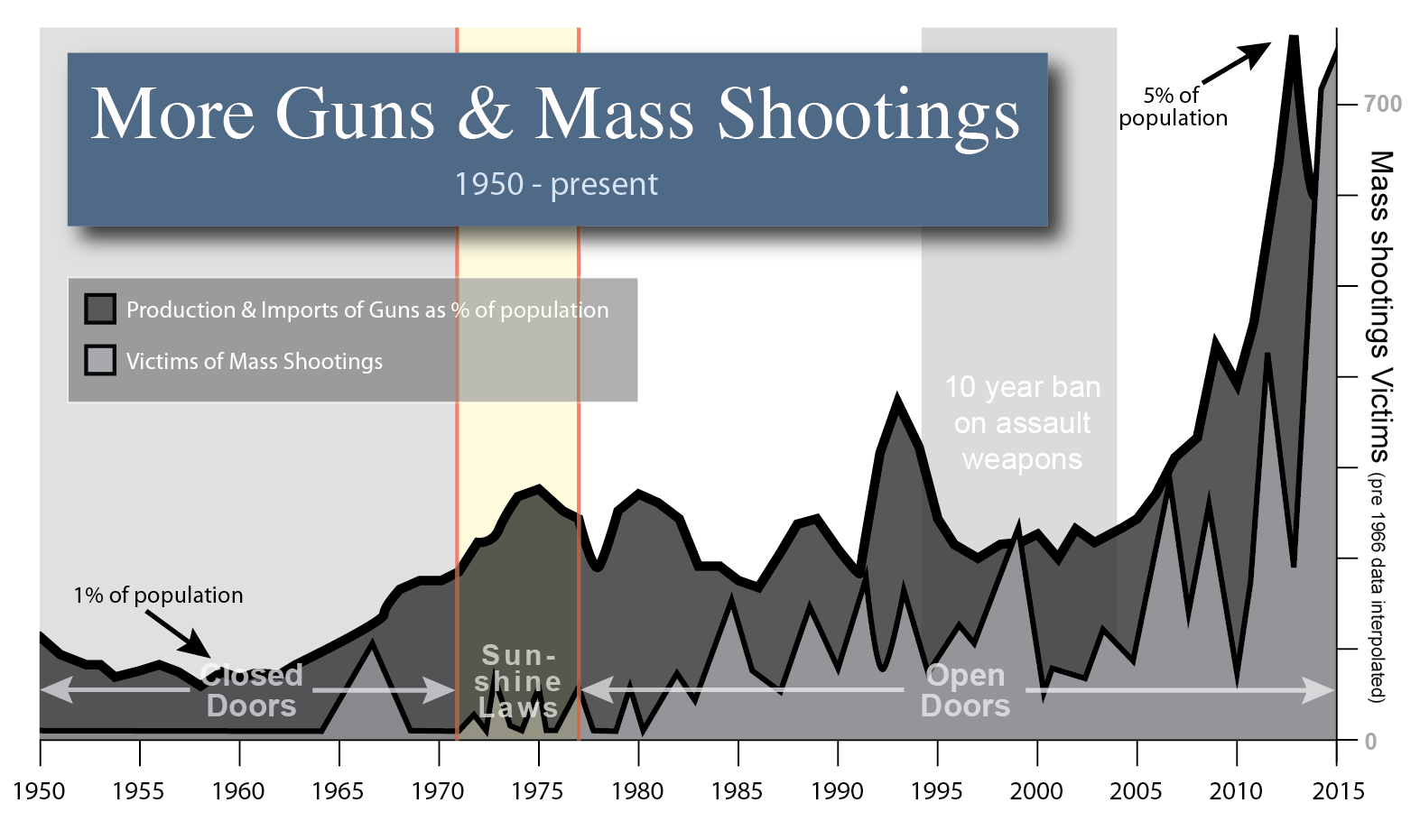

Reorganization Act of 1970

And other congressional moves toward transparency

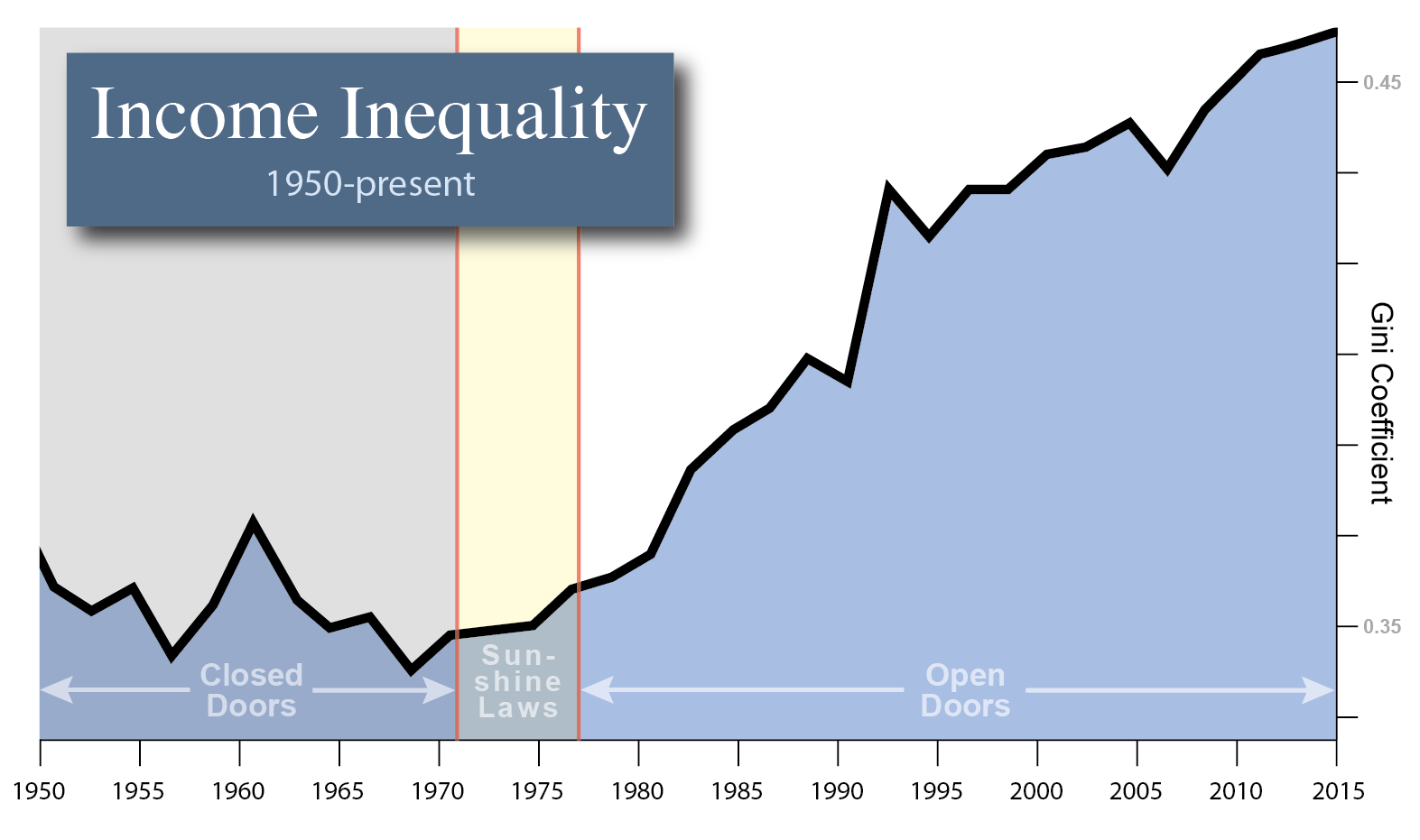

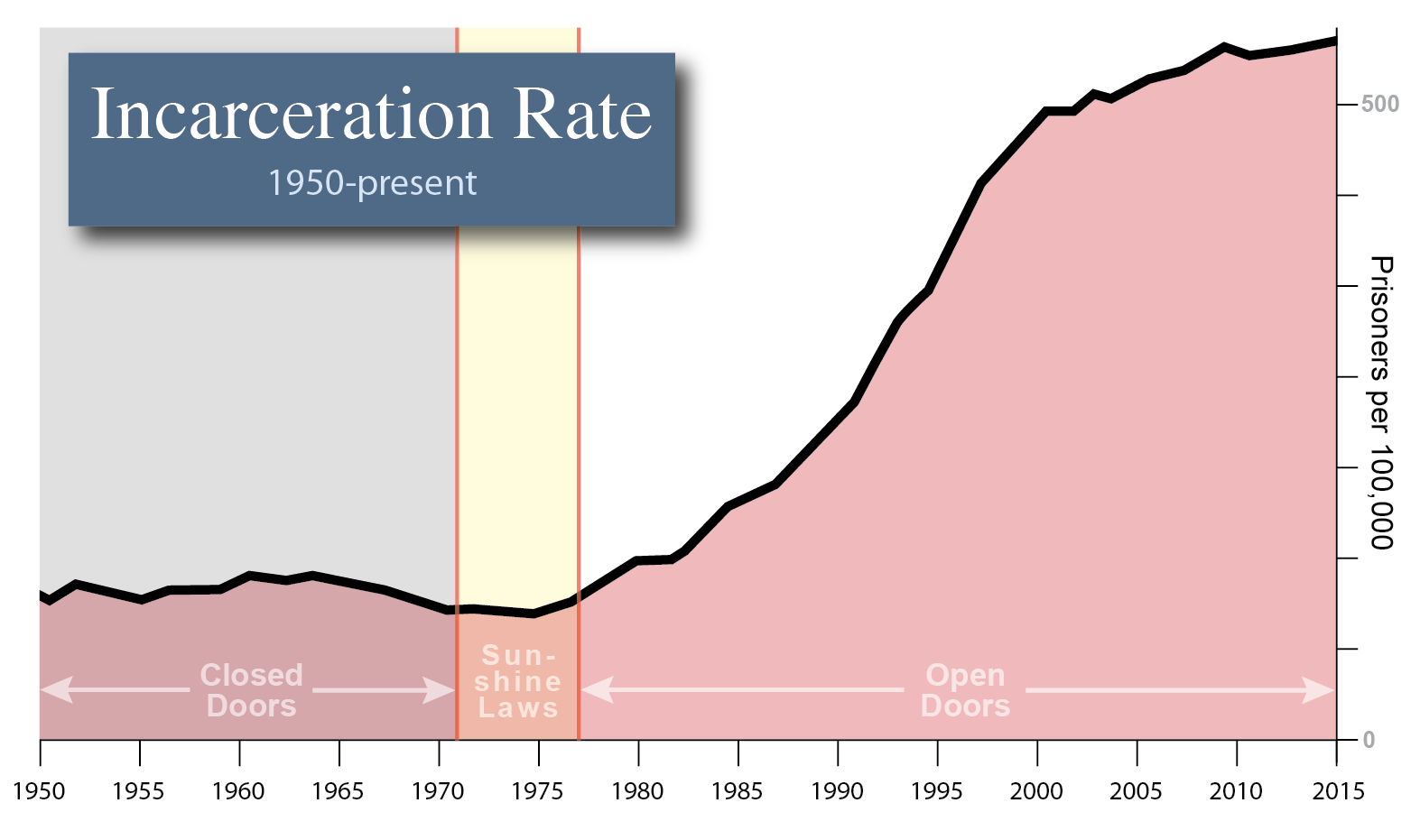

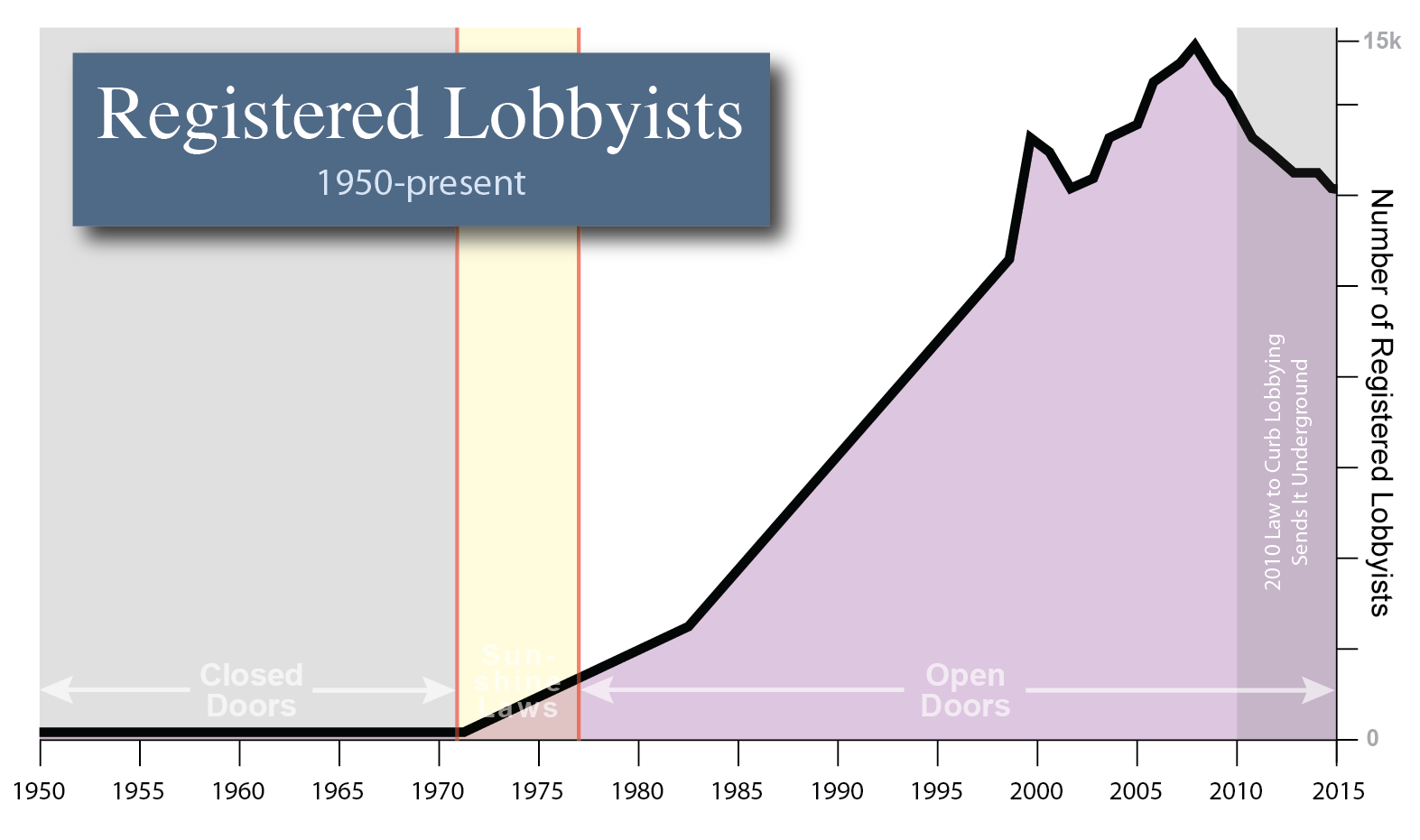

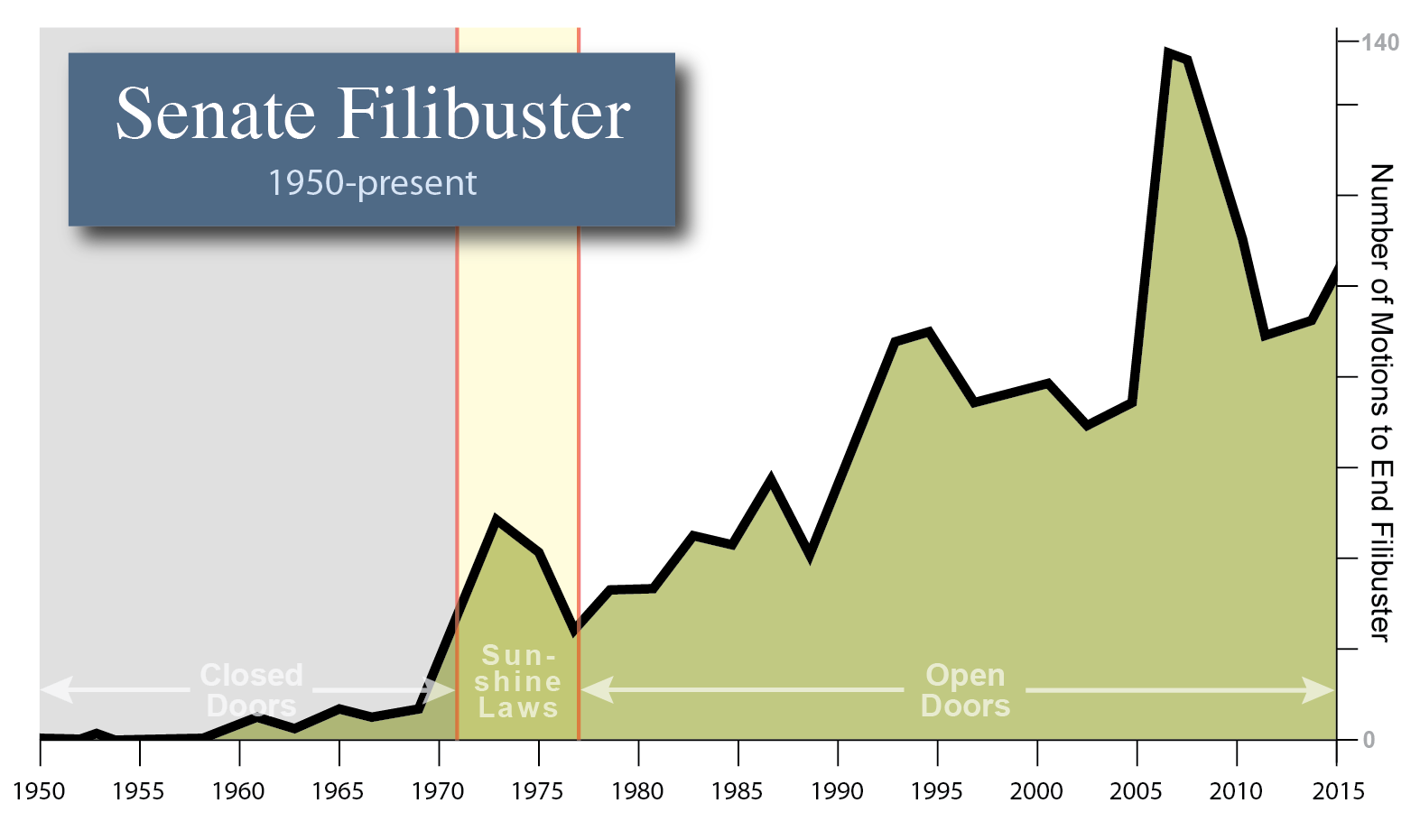

The unheralded law that thrust transparency on Congress and opened the floodgates for lobbyists in Washington DC.

By James D’Angelo and David King – November 12, 2023

If we open up our [committees] to the public, every lobbyist in America is going to be there.Rep Harley Staggers (D-WV) 1973

Congress Opens Up their Sessions

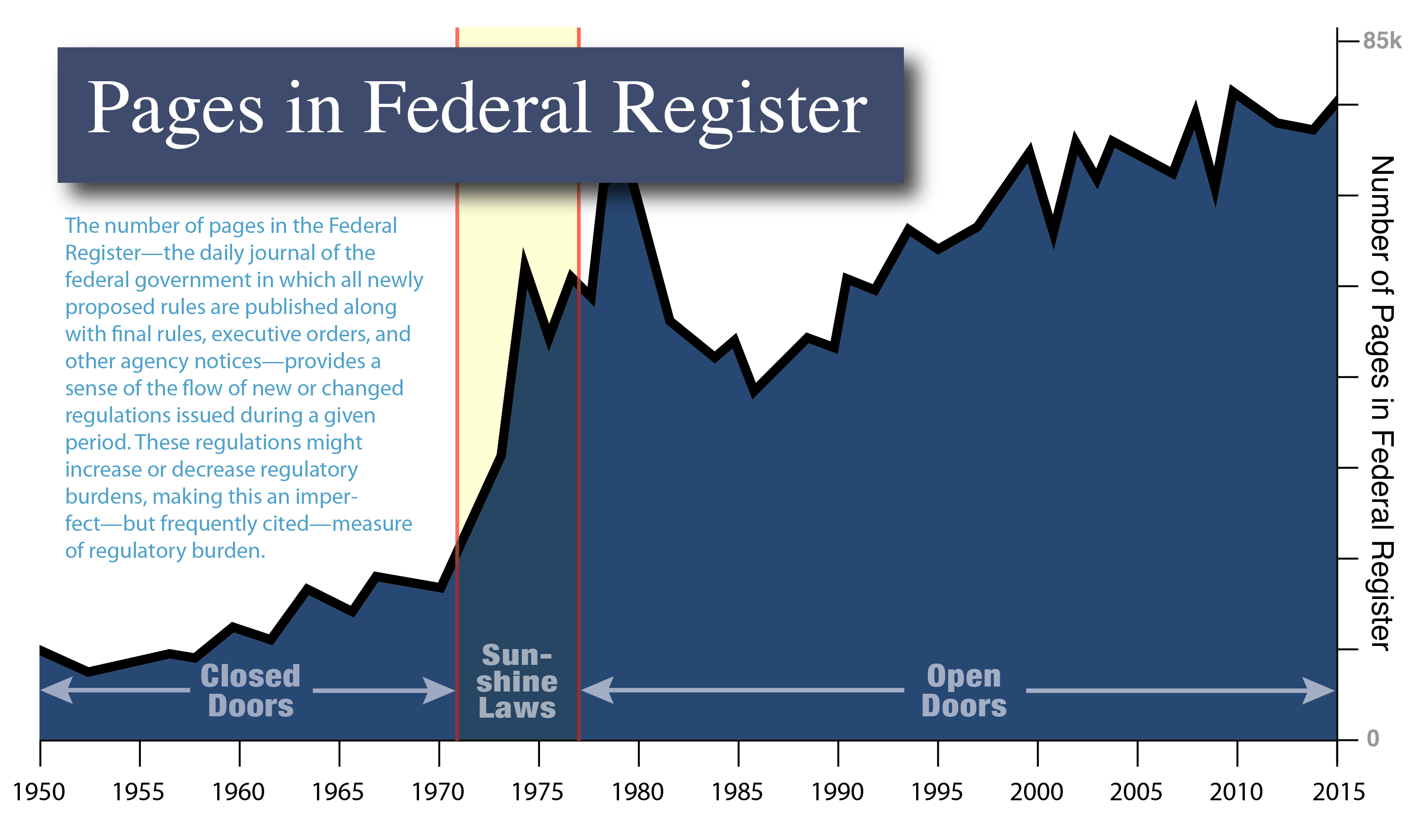

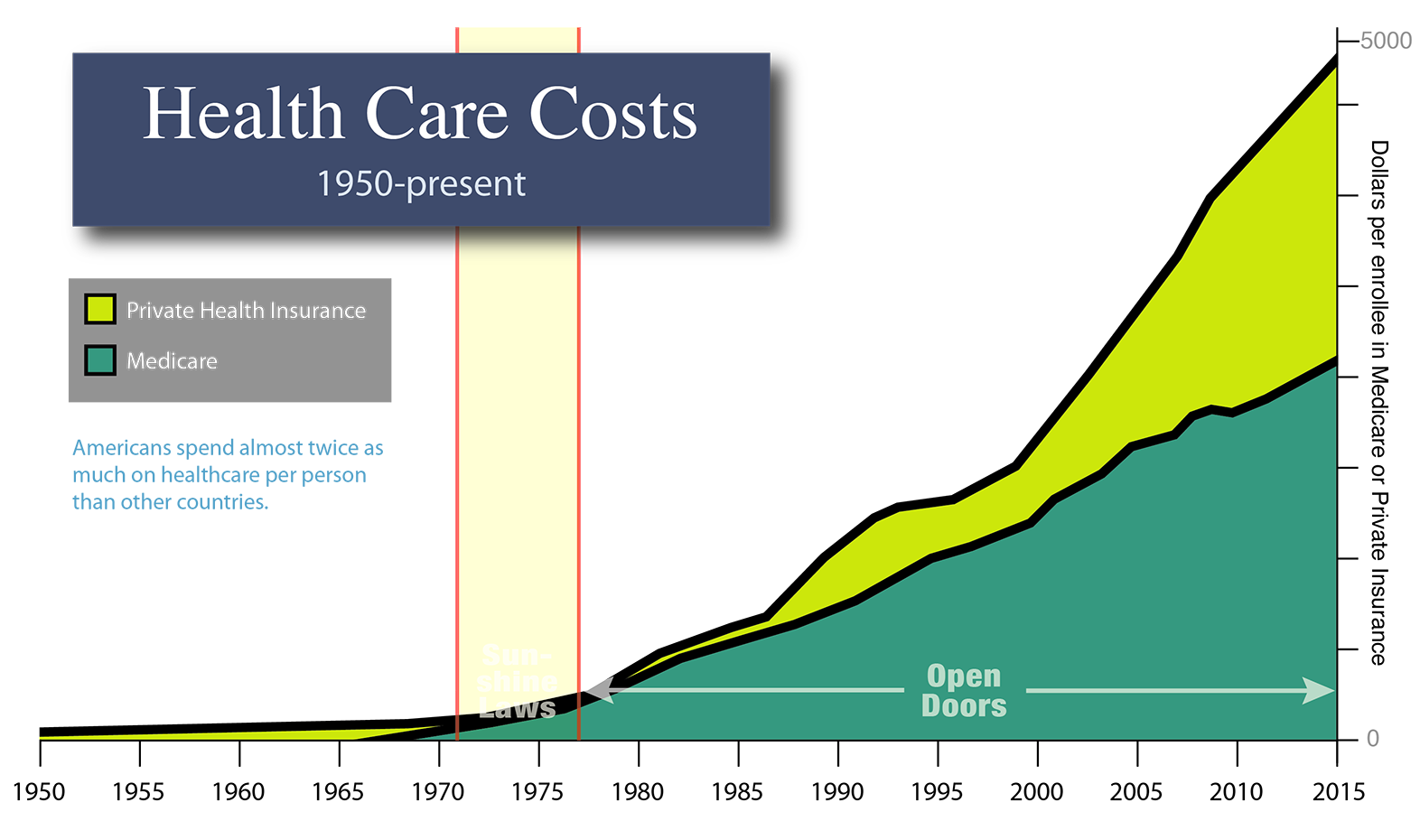

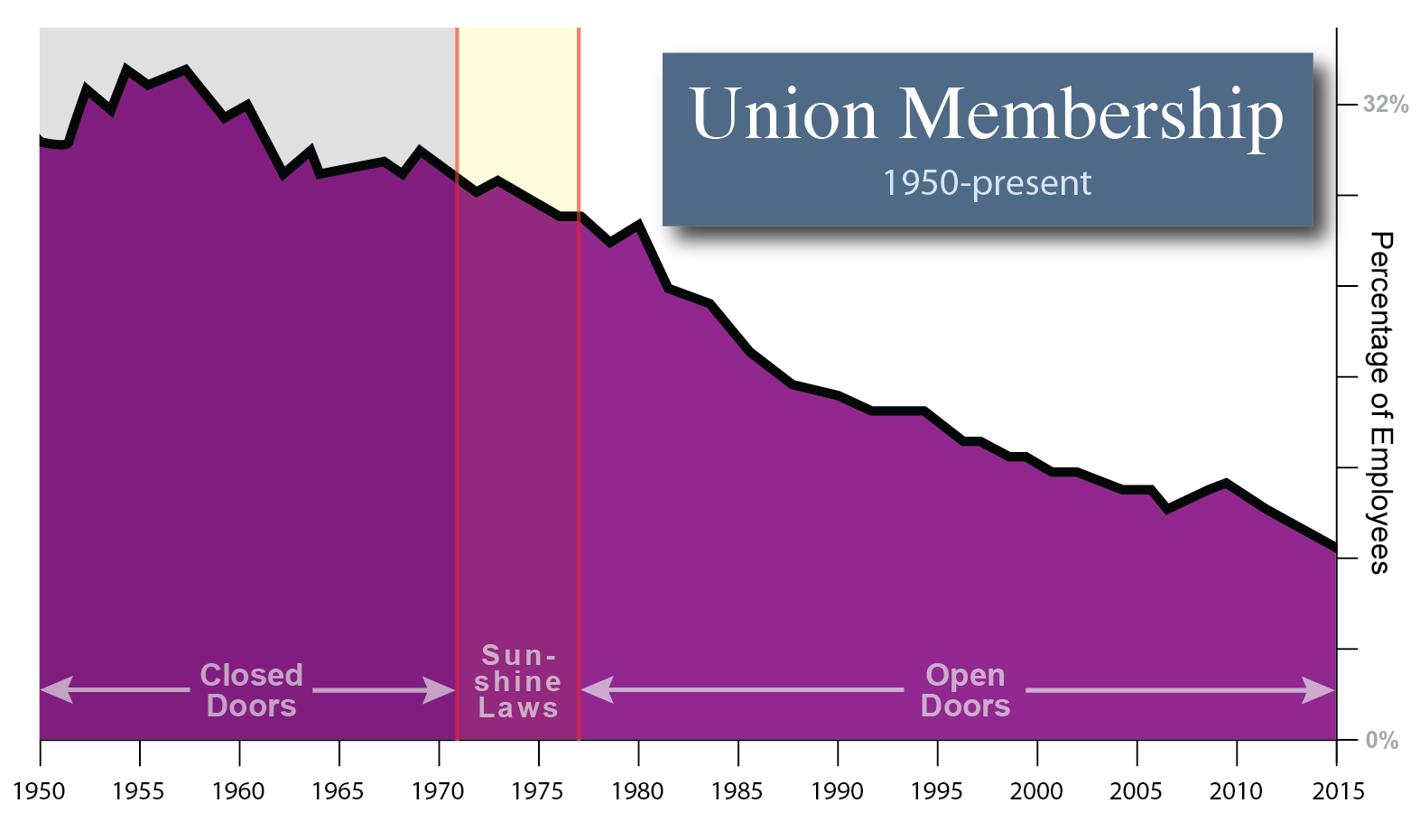

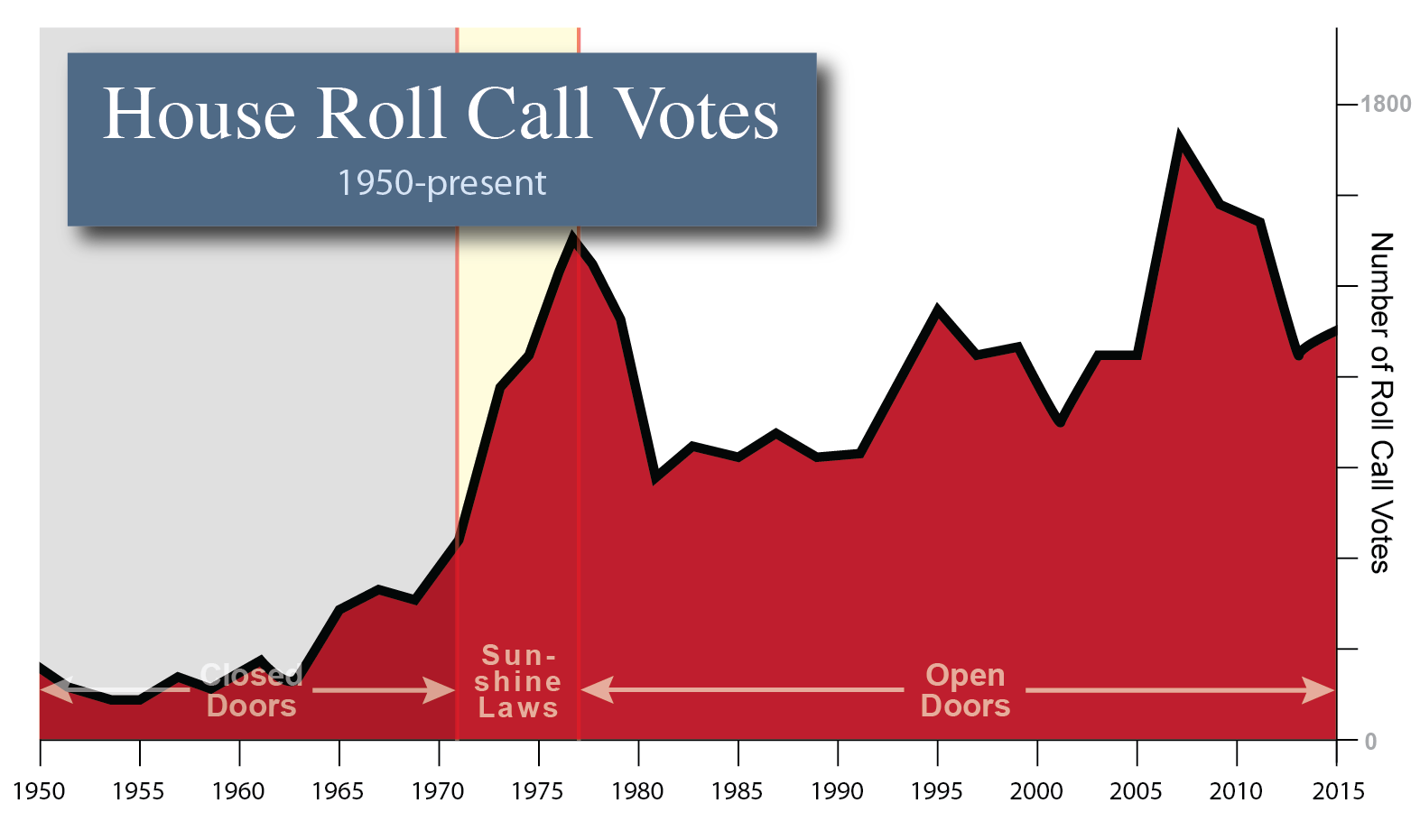

In the early 1970s Congress opened up its proceedings in a number of important ways. Decades before the term ‘transparency’ was associated with discussions of government, numerous important transparency measures were passed. The most salient was the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970 which is perhaps the strongest piece of transparency legislation in US History, surpassing even the 1966 Freedom of Information Act and the 1972 Federal Advisory Committee Act.

Often overlooked, the 1970 LRA made numerous changes in how Congress operates, especially with respect to transparency. These actions proved more beneficial to lobbyists and special interests than they were to the general public. Scholar George Kennedy summarizes:

The changes included open business meetings of committees, with disclosure of roll call votes taken in committee; public notice of committee meetings and provision for broadcast coverage; open hearings of appropriations committees of both houses; with mandatory roll call votes on appropriation bills.George Kennedy 1978

Advocates of Openness

This is confirmed by Norm Ornstein and Thomas Mann:

Nearly all key committee meetings – at which bills were “marked up,” put together, and amended piece-by-piece, and where conference panels met – were held in secret, behind closed doors. In the absence of the public and press, and with no recorded votes, chairmen could wheel and deal, and cajole or coerce their members, relatively free of outside pressure or influence. On the floor, too, most votes on amendments were unrecorded, and thus there was no formal record of how individual lawmakers had voted. Thomas Mann & Norm Ornstein 2006

The Broken Branch

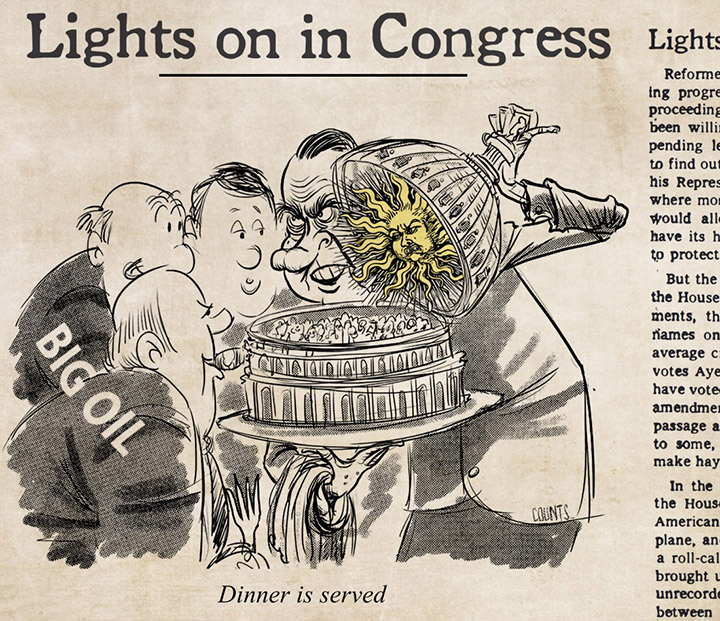

Dave Counts - “Dinner is served.”

In 1970, President Nixon signed The Legislative Reorganization Act opening congressional committees to the glare of powerful interests.

Dave Counts - “Dinner is served.”

Before the passage of the LRA, the vast majority of all legislation was discussed in secret. In 1923, Representative Charles Brown underlines this in the congressional record:

Under our rules today 95 per cent of all of the business that we transact is transacted in the Committee of the Whole, and 95 percent of the votes cast in this body under our present rules are cast in the Committee of the Whole, where, under the rules, no record vote can be had and which in effect is a secret ballot.Charles Brown 1923

Congressional Record

George Kennedy claims the same level of secrecy held right up to 1970:

Virtually all the meetings at which bills were actually written or voted on were closed to the public. Also closed almost without exception were the ‘mark-up sessions’ at which bills were reworded, amended and written in the form in which they would be submitted to the full houses. Senate-House conference committees, which President Nixon once described as ‘probably the most important legislative entities in our government,’ customarily excluded not only press and public but even other members of Congress from their sessions.George Kennedy 1978

Advocates of Openness

Yet while most committees were opened by the mid-1970s, the conference committees were finally thrust open in the mid-late 1970s resulting in an immediate change of legislative behavior. Fareed Zakaria cites this as a fundamental change.

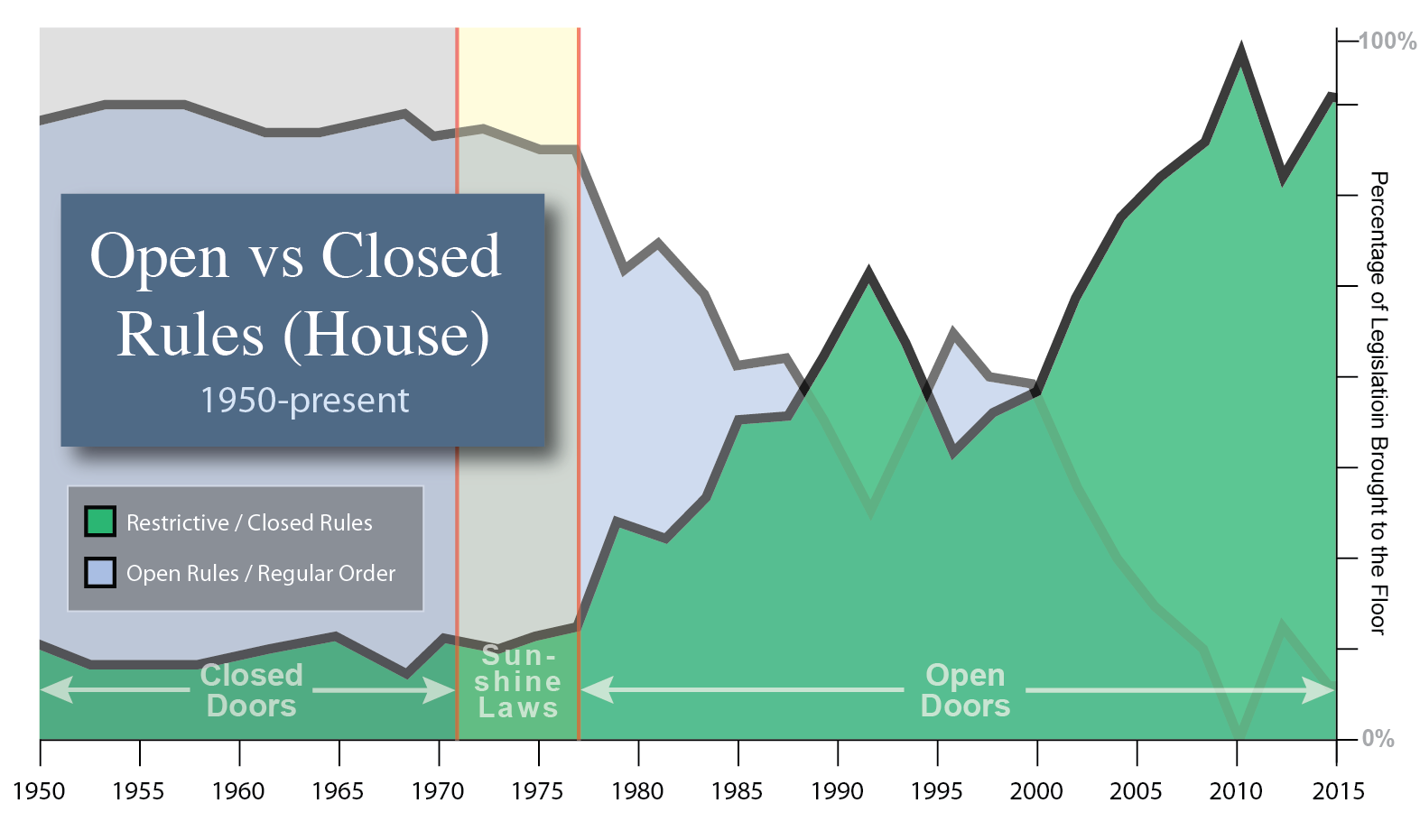

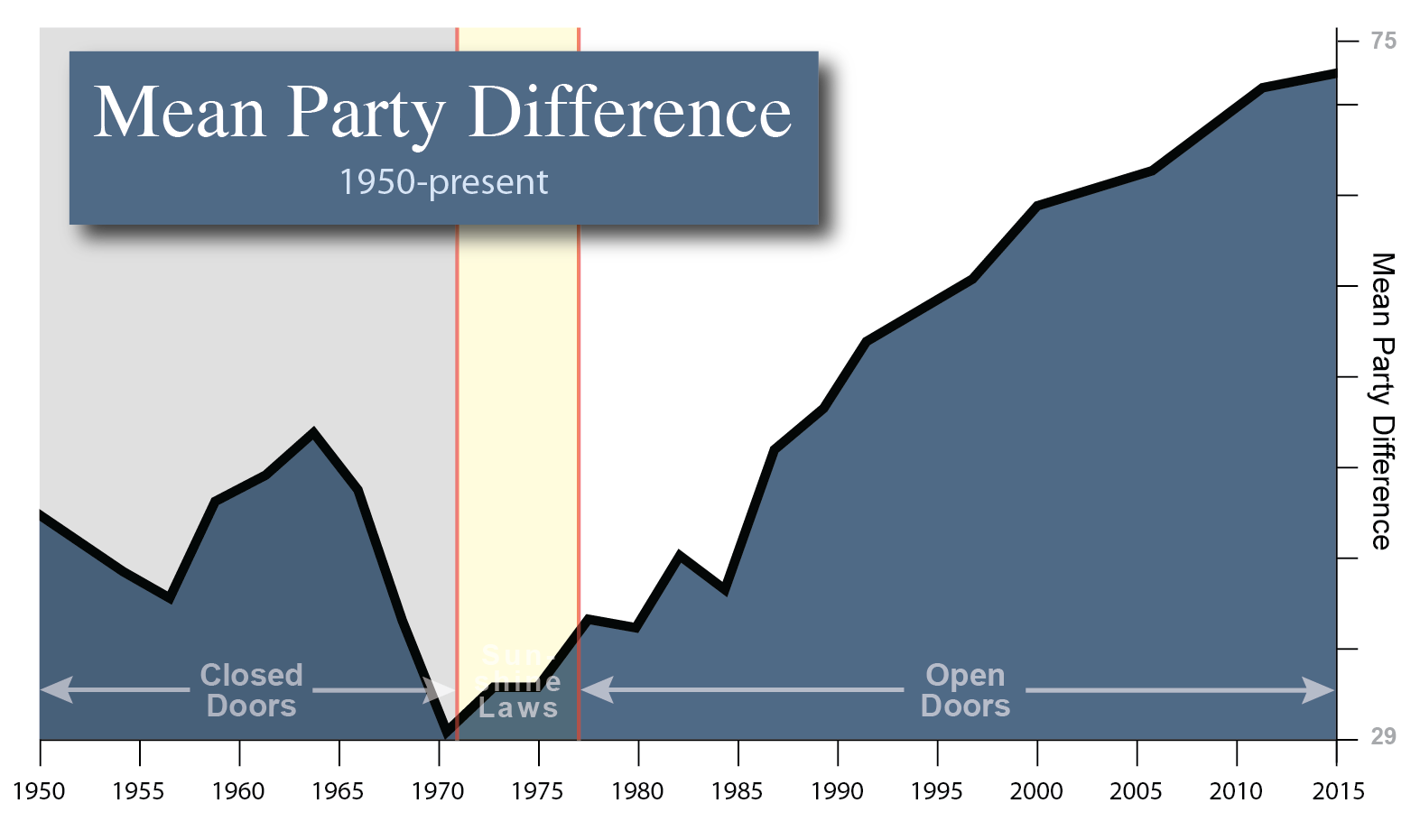

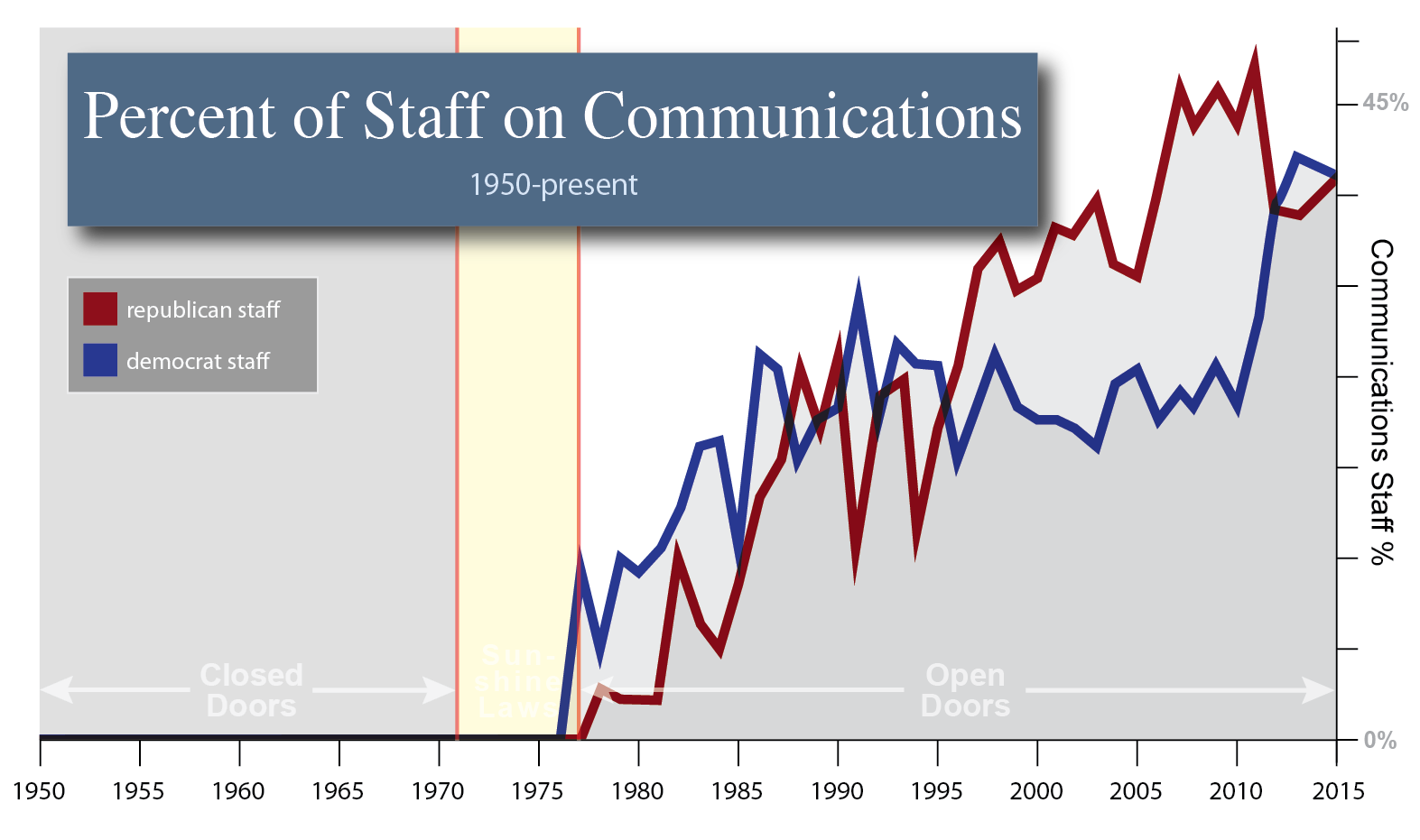

Among the most consequential reforms of the 1970s was the move toward open committee meetings and recorded votes. Committee chairs used to run meetings at which legislation was “marked up” behind closed doors. Only members and a handful of senior staff were present. By 1973 not only were the meetings open to anyone, but every vote was formally recorded. Before this, in voting on amendments members would walk down aisles for the ayes and nays. The final count would be recorded but not the stand of each individual member. Now each member has to vote publicly on every amendment. The purpose of these changes was to make Congress more open and responsive. And so it has become – to money, lobbyists, and special interests.Fareed Zakaria 2003

Future of Freedom

But to focus exclusively on the 1970 LRA (which is discussed in greater depth below) is foolish. There were other important yet ‘minor’ rules changes that worked to the benefit of lobbying and outside pressure as well, all focused on transparency, and allowed lobbyists to finally come in from the lobby.

Perhaps the most important of those more ‘subtle’ changes was the 1973 H Res 259 which opened committees (see this 1973 New York Times piece as well), and the 1975 opening of the conference committees, covered by Langly and Oleszek here. And whose effects were noted by scholar Pildes from NYU Law, below:

After the 1976 Government in the Sunshine Act required that congressional committee meetings be public, surveys of senators soon concluded that these open meeting requirements were the largest single cause of a decline in the ability to negotiate and to make politically difficult trade-offs.Richard Pildes 2014

Romanticizing Democracy

Like other scholars, Pildes could find little, if any, benefits of this increased openness, yet the observable problems created by transparency mounted. And looking back as far as 1911 when congressional hearings were thrust into the open, pundits – like this 1929 author suggest – were concerned:

The [1911] rules served to break up the small clique in power and gave the representatives generally more control of procedure. This was a blow to the old lobby. It was patently impossible to attempt to cajole or bribe an entire Congress. Another reform in the legislative procedure that tended to improve the methods of the lobbyists was the adoption on the part of Congress in the early years of this century of the policy of holding on all important bills, open committee hearings which the proponents and the opponents of a measure might attend and there state, frankly and publicly, their attitude toward the legislation under consideration. Only the hearings of the Appropriations Committee are now held in executive session as a general rule. By thus openly testifying before committees the lobbyists of legitimate interests can make their appeal to a much wider audience.Pendelton Herring 1929

Group Representation Before Congress

Despite this history, the 1970s reforms continued for decades. In 1995 the rules were further amended to require that: on all votes conducted in a committee markup on a reported bill or other matter reported to the House, the report contain the number of votes cast for or against and how individual members voted. In the Senate, the rules are less specific. They require that a committee’s report on a bill include the results of roll-call votes on “any measure or any amendment thereto” unless the results have been announced previously by the committee. Senate rules require that in reporting roll-call votes the position of each voting member is to be disclosed (Senate Rule XXVI.7(b)).

Speaker Gingrich in the 104th Congress advanced openness reforms which largely echoed efforts begun by Democrats in the 1970s reform era to allow the sunshine in to ‘disinfect’ Congress.William F. Connelly 2013

Partisan, Polarized, Yet Not Dysfunctional?

To date, there is but one scholar (Lee Drutman) who argues that the Legislative Reorganization Act was beneficial. We discuss the odd circumstances that make him supportive, here. But, it strikes us as difficult to to intepret Drutman’s work without seeing a self-serving bent on his part.

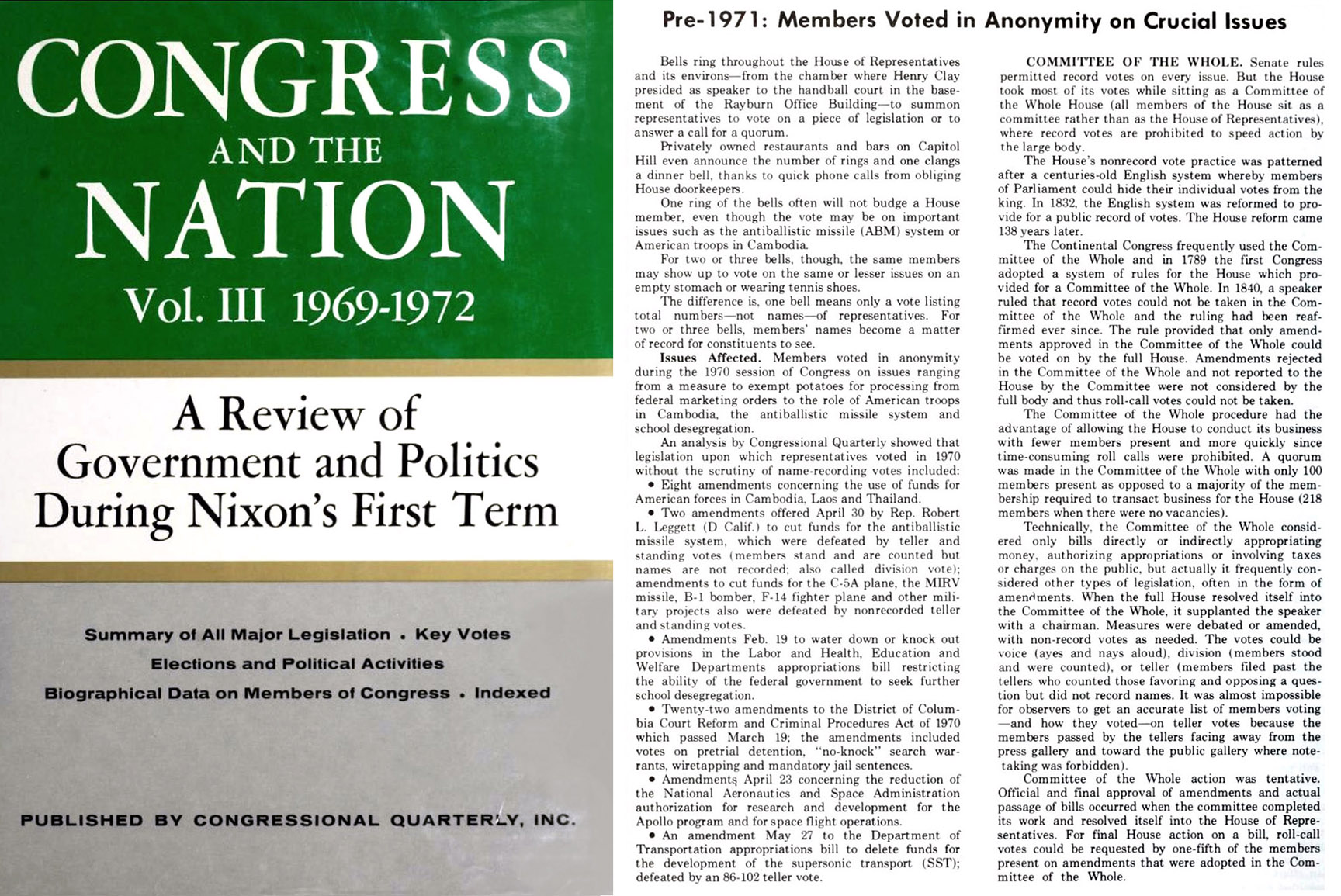

Congressional Quarterly 1973 - Pre-1971 Members Voted in Anonymity

Text: The House took most of its votes while sitting as a Committee of the Whole House (all members of the House sit as a committee rather than as the House of Representatives), where record votes are prohibited to speed action by the large body. The House’s nonrecord vote practice was patterned after a centuries-old English system whereby members of Parliament could hide their individual votes from the king. In 1832, the English system was reformed to provide for a public record of votes. The Continental Congress frequently used the Committee of the Whole and in 1789 the first Congress adopted a system of rules for the House which provided for a Committee of the Whole. In 1840, a speaker ruled that record votes could not be taken in the Committee of the Whole and the ruling had been reaffirmed ever since.

Congressional Quarterly 1973 - Pre-1971 Members Voted in Anonymity

The Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970

The Introduction of Congressional Transparency

This landmark legislation launched the congressional reforms of the seventies, transforming the institution more than any event or series of events since the overthrow of Speaker CannonDonald Wolfensberger 2000

Congress and the People

By far the most significant anti-secrecy provision in the [1970] act dealt with disclosure of House members’ votes in Committee of the Whole. The House often makes its most important policy decisions in that committee, but for 180 years its precedents had forbidden the recording of names in these votes.Walter Kravitz 1990

The Legsilative Reorganization Act

Andrew Glass 2009 - Nixon Signs 1970 LRA

On this day in 1970, President Richard Nixon signed into law major changes in the was Congress would conduct its business. The reforms paved the was for the installation of electronic voting machines in the House chamber. When introduced on Jan. 23, 1973, these revolutionized the congressional voting procedures. The reforms also made House and Senate procedures more transparent. Thereafter, all committee hearings were to be held in public, except for national Security matters or appropriations.

Andrew Glass 2009 - Nixon Signs 1970 LRA

The Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970 (Pub.L. 91–510 pdf | Wikipedia) was an act of the United States Congress to “improve the operation of the legislative branch of the Federal Government, and for other purposes.” The act focused mainly on the rules that governed congressional committee procedures, decreasing the power of the chair and empowering minority members, and on making House and Senate processes more transparent. Almost as a second thought, they added rules for recorded votes and broadcasting of committees.

The Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970

From the 1995 Encyclopedia on Congress by David King

The Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970 (P.L. 91-510; 84 Stat. 1140-1204) was the first major legislative reform bill enacted after the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946. The 1970 act encouraged open committee meetings and hearings, required that committee roll-call votes be made public, allowed for television and radio broadcasting of House committee hearings, and formalized rules for debating conference committee reports. Many of these reforms were adopted in the name of opening up the legislative process to the public eye. The reform of longest-lasting significance provided that House votes in the Committee of the Whole be recorded on request, which ended the secrecy often surrounding members’ votes on important measures.

Within a decade after the 1946 reorganization act, a handful of reform-minded legislators had begun calling for revisions to deal with the act's unanticipated consequences. By reducing the number of committee chairmen while strengthening congressional oversight of the executive branch, the act greatly expanded the chairmen’s power. In party caucuses, seniority was the guiding rule for appointing committee chairmen. A disproportionate number of chairmen were long-serving southern Democrats who effectively veto d a more liberal social Welfare and civil rights agenda throughout the 1950s and much of the 1960s.

In 1965, Congress established the Joint Committee on the Organization of Congress, headed by Sen. A. S. Mike Monroney (D-Okla.) and Rep. Ray J. Madden (D-Ind.). The joint committee’s final report in 1966 recommended limiting the powers of chairmen, reducing the number of committee assignments, improving committee staff, and expanding the Legislative Reference Service (later renamed the Congressional Research Service). In 1967, the Senate passed a bill (S. 355) largely based on the Joint committee's recommendations, but the bill languished in the House in the face of fierce opposition from committee chairmen.

In a move that surprised most observers, two House Rules Committee members, B. F. Sisk (D-Calif.) and Richard W. Bolling (D-Mo.), pushed for a special subcommittee to consider legislative reform in 1969. The result was House Report 91-1215, which became the basis for the 1970 Legislative Reorganization Act. Most of the provisions in the 1970 bill opened up the legislative process through what are called sunshine provisions (i.e., measures that increase public access by “letting the sunshine in” on legislative proceedings). Very few of the proposals to limit the powers of committee chairmen and to weaken seniority that had been discussed by the 1969 join t committee survived in the bill.

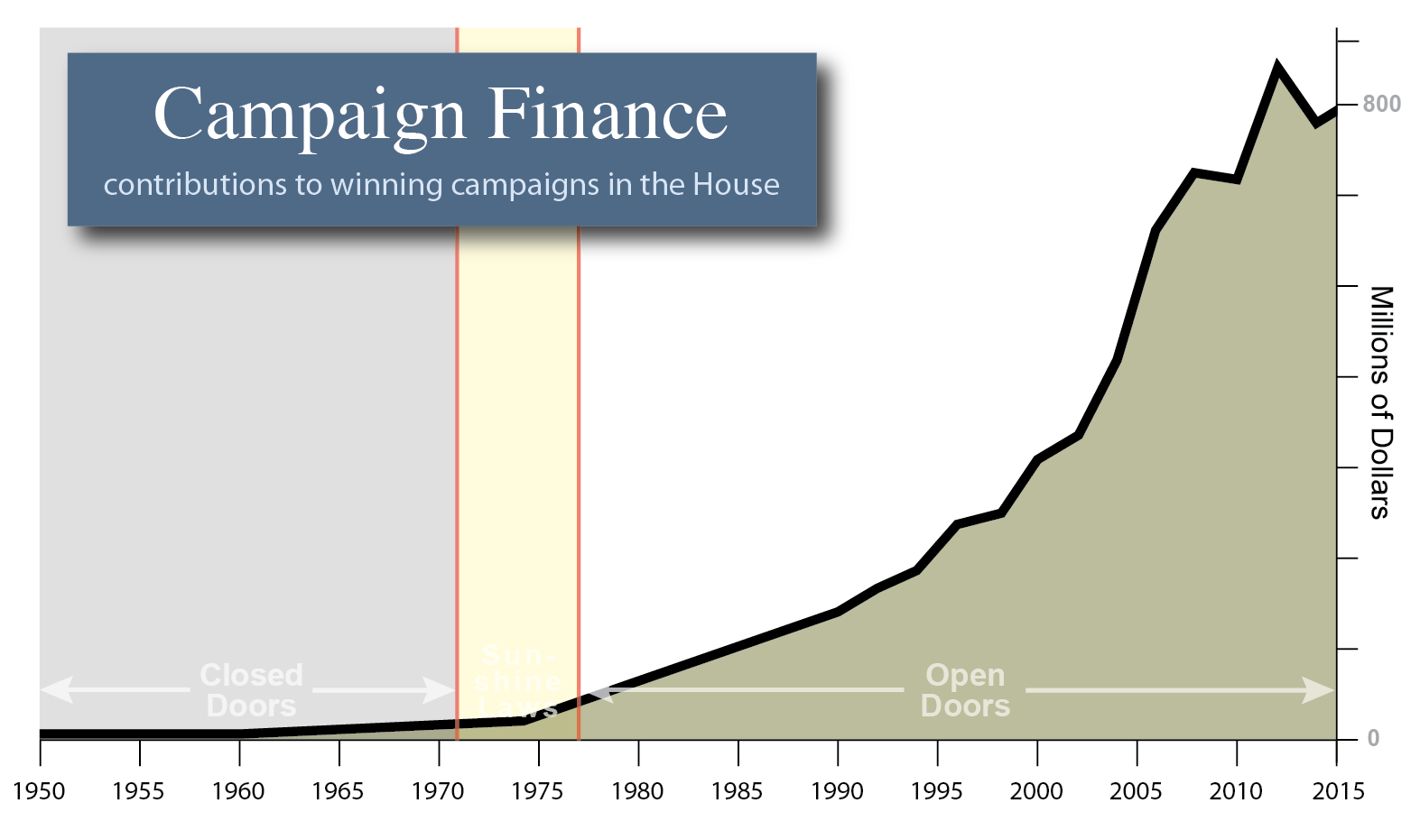

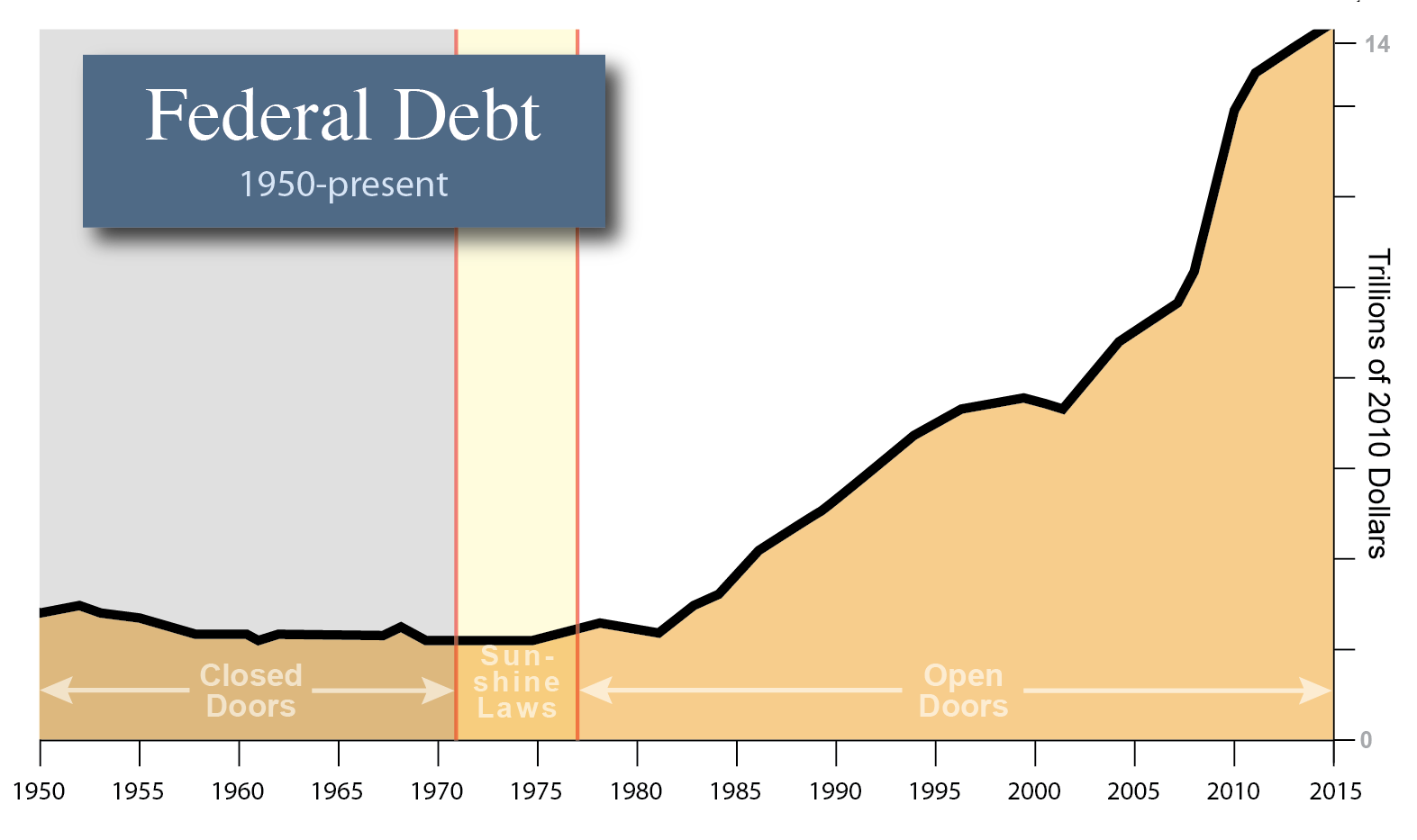

Congressional reforms, particularly the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970, reduced the power of committee chairs and opened Washington to a barrage of interest group activists, lobbyists, and campaign funders.Benjamin C. Waterhouse 2014

Lobbying America

In ten days of floor debate, 65 amendments were considered. A package of ten amendments (nine of which passed) was presented on the House floor by a bipartisan coalition of reformers. The House passed its version of the reorganization act 326 to 19 on 17 September 1970. The Senate made minor changes, passing the bill 59 to 5 on 6 October, and the House accepted the Senate's modifications on 8 October.

The Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970 was a harbinger of things to come. While limitations on seniority were modest, within a year the House and Senate had passed resolutions stating that the selection of committee chairmen need not be based solely on seniority. In 1973, the House “Subcommittee Bill of Rights” mandated that legislation be referred to subcommittees, further weakening the power of the chairmen of full committees.

[See also Government in the Sunshine Act.]

BIBLIOGRAPHY Davidson, Roger H. “Inertia and Change: The Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970.” In On Capitol Hill. Edited by John F. Bibby and Roger H. Davidson. 2d ed. 1972.

Kravitz, Walter. “The Advent of the Modern Congress: The Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 15 (August 1990): 375-399.

Key Sections and Clauses of the 1970 LRA

The House of Representatives

Below is section 104, clause 27b, of the 1970 LRA addressing the procedural changes required in the House of Representatives:

PUBLIC ANNOUNCEMENT OF COMMITTEE VOTES SEC. 104. (b) Clause 27(b) of Rule XI of the Rules of the House of Representatives is amended by adding at the end thereof the following: “The result of each roll-call vote in any meeting of any committee shall be made available by that committee for inspection by the public at reasonable times in the offices of that committee. Information so available for public inspection shall include a description of the amendment, motion, order, or other proposition and the name of each Member voting for and each Member voting against such amendment, motion, order, or proposition, and whether by proxy or in person, and the names of those Members present but not voting. With respect to each record vote by any committee on each motion to report any bill or resolution of a public character, the total number of votes cast for, and the total number of votes cast against the reporting of such bill or resolution shall be included in the committee report.”

Subsequent rule changes in the House led to the 1973 introduction of enormous voting boards, which dramatically increased the ability for outsiders to monitor the votes.

The Senate

Below is section 103 and 133b, the actual text that changed the way the Senate votes. It is important to note, that while the below wording looks the same as the House version above, the difference was in some ways less severe for two reasons (1) the Senate did not have the ability to congregate in the ‘Committee of the Whole’ (2) the Senate had already called for open proceedings starting in 1929 (but which did not ramp up into common usage until the 1930s and 1940s). Yet many scholars overlook the fact that all important Senate committees and markups were closed before the LRA as well. So the impact is likely just as strong in the Senate. The changes to Senate procedure brought by the 1970 LRA resulted in paragraph 5(b) of Rule XXVI of the Standing Rules of the Senate.

OPEN COMMITTEEE HEARINGS

SEC. 103. (a) Section 133(b) of the Legislative Reorganization Act 60 Stat. 831. of 1946 (2 U.S.C. 190a(b)) is amended by inserting immediately after ( b ) the following: “Meetings for the transaction of business of each standing committee of the Senate, other than for the conduct of hearings, shall be open to the public except during executive sessions for marking up bills or for voting or when the committee by majority vote orders an executive session.” (b) Clause 26 of Rule XI of the Rules of the House of Representatives, as amended by section 102(b) of this Act, is further amended by adding at the end thereof the following new paragraph: “( f ) Meetings for the transaction of business of each standing committee shall be open to the public except when the committee, by majority vote, determines otherwise. This paragraph does not apply to open committee hearings which are provided for by paragraphs (f) (2) and (g) (3) of clause 27 of this Rule.”

Subsequent rule changes in the Senate led to the following:

All committees must make public a video, transcript, or audio recording of each open hearing of the committee within 21 days of the hearing. These shall be made available to the public “through the Internet” (Rule XXVI,paragraph 5(2)(A)).

Below is section 116, the wording that opened the committees to electronic media, television, CNN, radio, etc.

BROADCASTING OF COMMITTEE HEARINGS

SEC. 116. (a) Section 133A(b) of the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946, as enacted by section 112(a) of this Act, is amended by adding at the end thereof the following: "Whenever any such hearing is open to the public, that hearing may be broadcast by radio or television, or both, under such rules as the committee may adopt."

For more references and articles on the LRA1970 see this reference section. Also check here (1970s NY Times coverage of the Act), here (scholarly article on Act), and here (Politico article from 2009).

CQ Quarterly

CQ Quarterly

The Senate before 1970

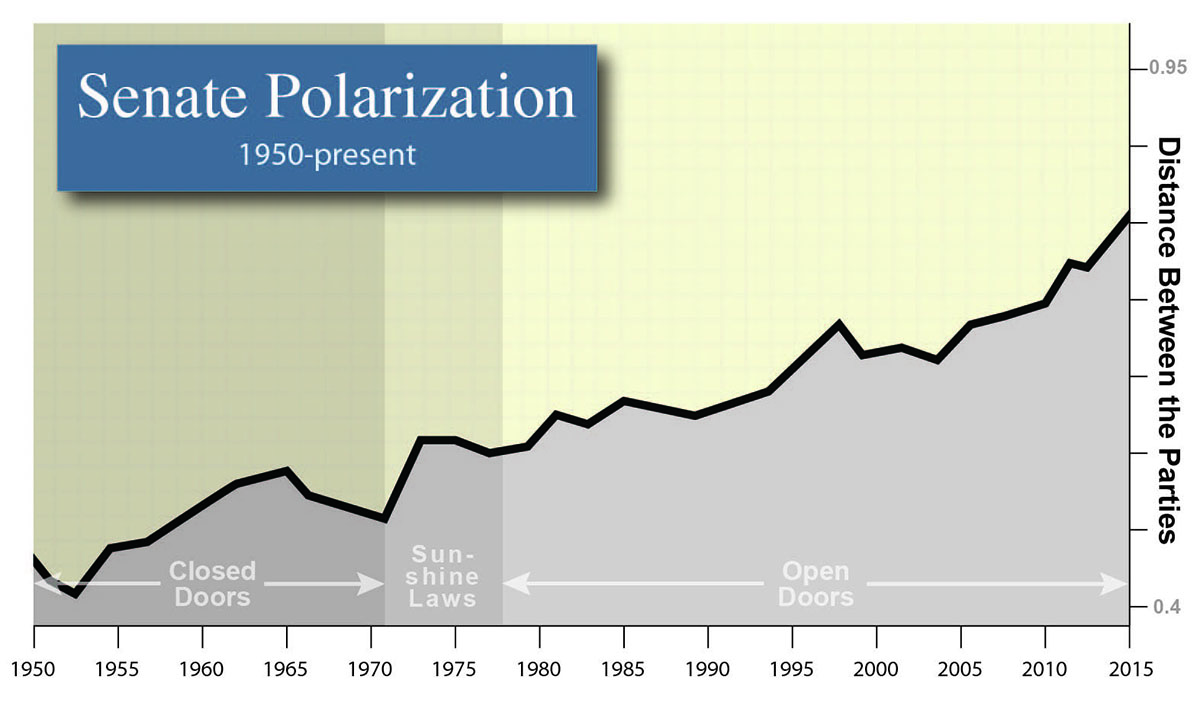

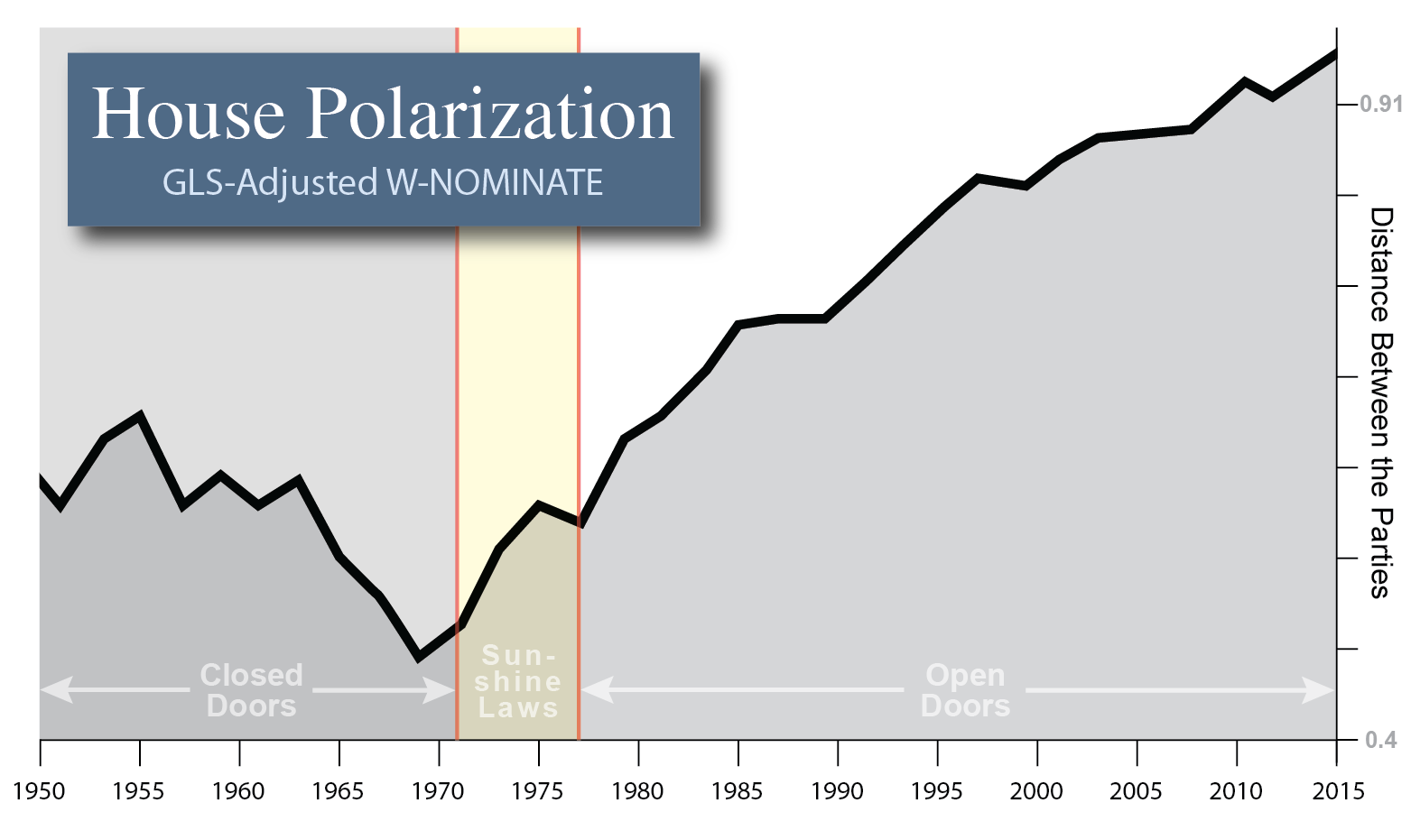

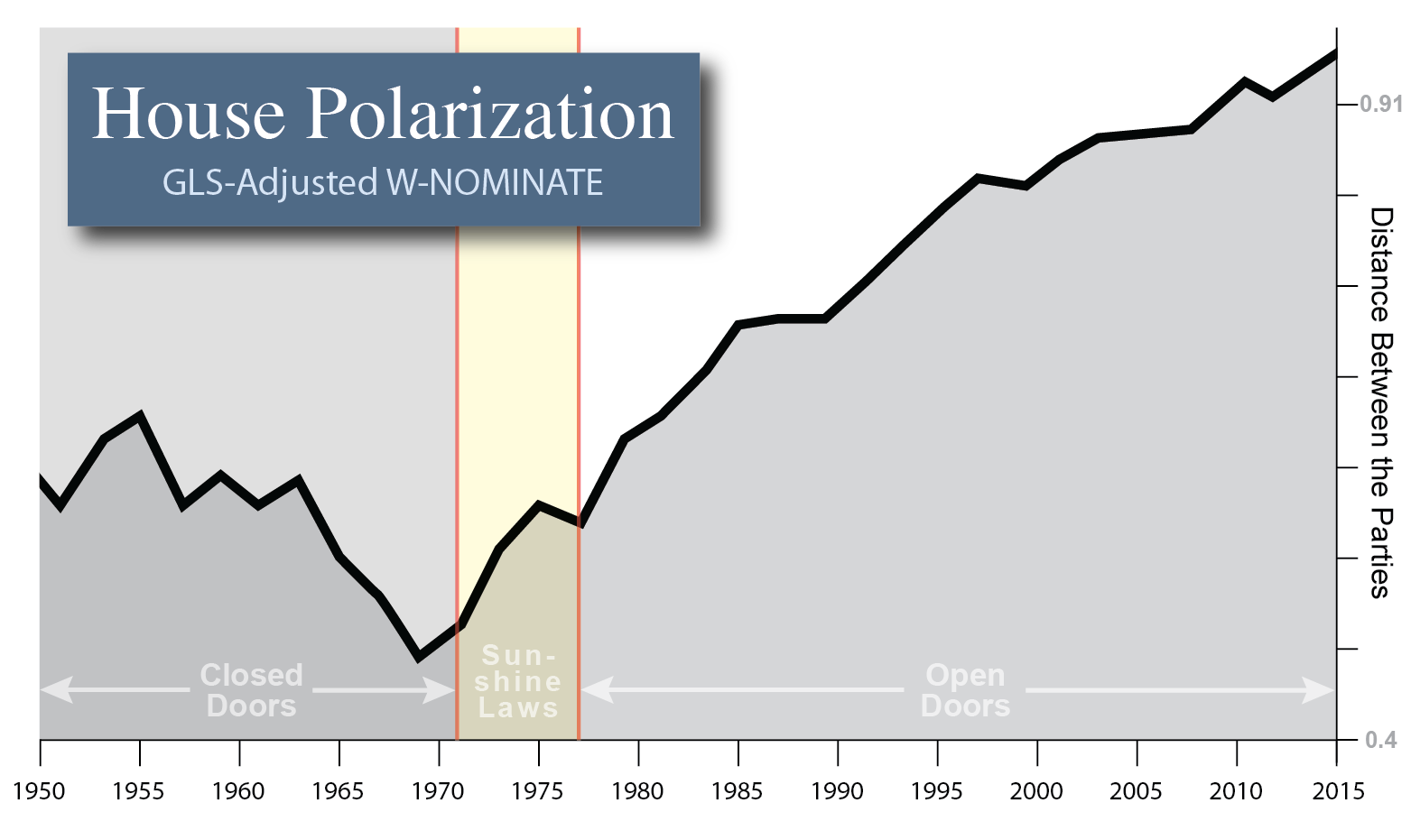

While the LRA expressly addressed both the House and the Senate (see above), there were important differences between the two chambers (with respect to transparency) before 1970. This article from the Senate archives covers a series of changes starting in 1929 to open the Senate. It talks about how the rules for executive sessions were changed to allow for more open committees, which really got going in the 1940s. Interestingly this aligns fairly well with what we know about Senate partisanship, Which can be compared to the more dramatic rise in polarization in the House (graphs below).

Freedom of Information Act (1966 & 1974)

The Introduction of Executive Transparency

It is worth noting that Supreme Court Justice Anton Scalia, Columbia Law Professor David Pozen, and others find similar problematic changes in the Executive Branch (via FOIA) occurring during this same time period – early 1970s. Scalia calls the transparency created by FOIA the “Taj Majal of unintended consequences.” And while FOIA was launched in 1966, he focuses on the extensive changes made to enforce and strengthen the Act in 1974.

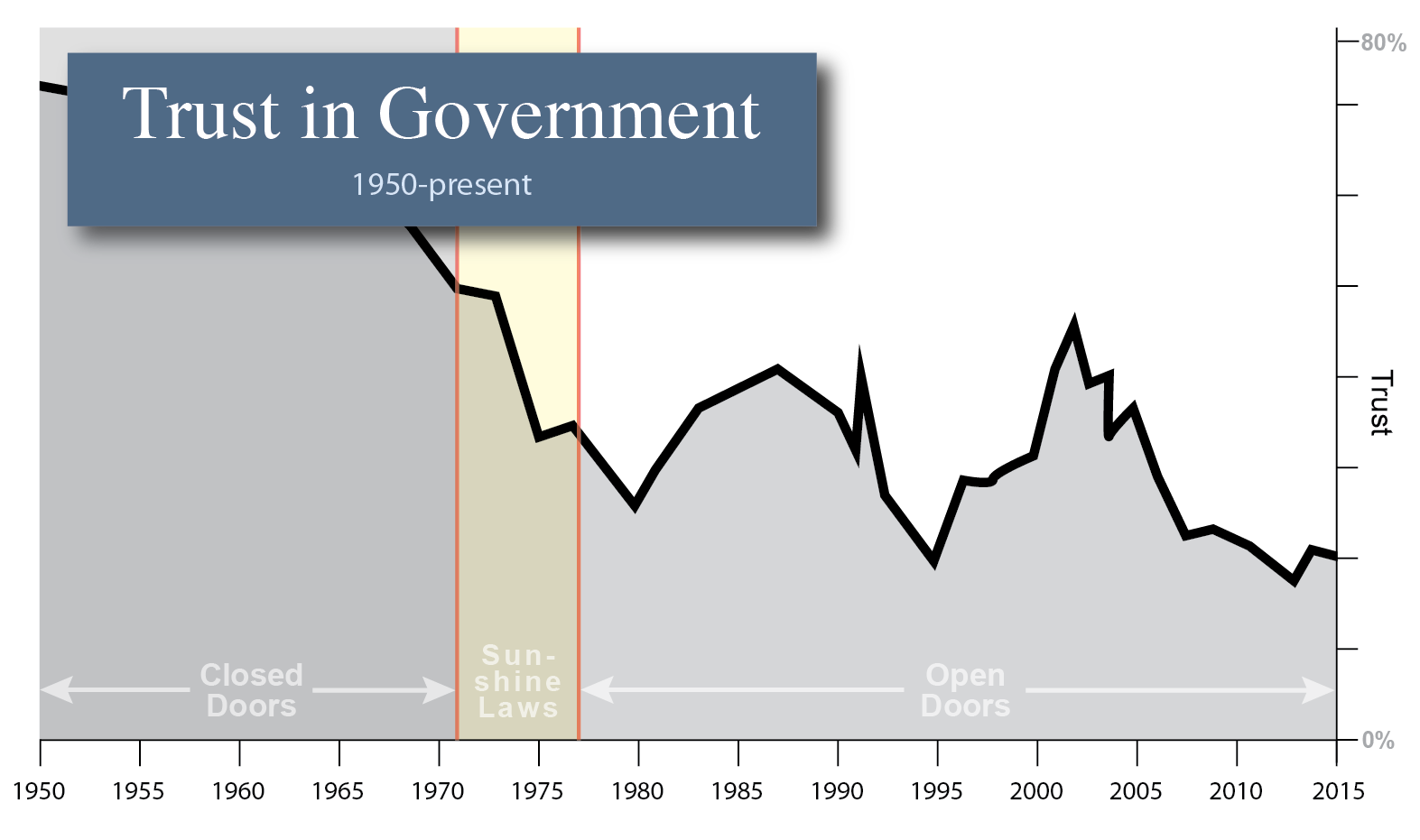

Almost all of the Freedom of Information Act’s current problems are attributable not to the original legislation enacted in 1966, but to the 1974 amendments. The 1966 version was a relatively toothless beast, sometimes kicked about shamelessly by the agencies. They delayed responses to requests for documents, replied with arbitrary denials, and overclassified documents to take advantage of the "national security" exemption. The ‘74 amendments were meant to remedy these defects but they went much further. They can in fact only be understood as the product of the extraordinary era that produced them-when “public interest law, consumerism, and investigative journalism” were at their zenith, public trust in the government at its nadir, and the executive branch and Congress functioning more like two separate governments than two branches of the same. Anton Scalia 1982

The Freedom Of Information Has No Clothes

Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA)

1972, 1993

The Extension of Executive Transparency

The Federal Advisory Committee Act was enacted in 1972 to ensure that advice by the various advisory committees formed over the years is objective and accessible to the public. FACA requires federal agencies to ensure that federal advisory committees make decisions that are independent and transparent. In fiscal year 2019, nearly 960 committees under FACA played a key role in informing public policy and government regulations.

“On motion, The Senate resumed the consideration of the message of the President of the United States, of the 10th instant, containing the nomination of John Rutledge, to be Chief Justice of the United States; and on motion to advise and consent to the appointment, agreeable to the nomination, * It passed in the negative, * Yeas ... 10, * Nays ... 14.” Why is the record so sparse? The explanation is simple - the Senate met in closed executive session when acting upon nominations until 1929. The only way for a nomination to be considered in open session before 1929 was if during a closed session, two-thirds of the senators agreed that the debate be opened. After 1844, any senator who leaked the proceedings of the secret debate on a nomination risked expulsion.

The Senate only finally changed its procedure in 1929, because it had been embarrassed by leaks of the proceedings on two controversial nominations, which had been published by a receptive press. The ensuing controversy eventually lead the Senate Rules Committee to propose an amendment, whereby open sessions would be permitted when ordered by a majority of the members. The proposed rules change also provided that the vote on nominations in closed session should be published in the record. Not satisfied, Senator Joseph Robinson of Arkansas offered a substitute amendment providing that sessions be open unless ordered closed by a majority vote Brian Rosenwald 2006

Advice and Consent

When the Senate meets in closed session, the records of that proceeding are sealed for a minimum of twenty years, unless the Senate votes to open them sooner. On particularly sensitive issues, such as national security or impeachment, it is common for such records to be closed for fifty years. For example, closed session records from the impeachment trials of three judges in the 1980s have been sealed for fifty years. The Senate can vote to change these access rules at any time. After fifty years, the Senate can vote to open the records or to keep them sealed even longer. The deliberations in President Andrew Johnson’s impeachment trial were unrecorded as well as secret.Marjorie Cohn 2000

Open-and-Shut: Senate Impeachment Deliberations Must Be Public

Potential Consequences of Congressional Sunshine

Lewis Powell 1971 - The Powell Memo

Lewis Powell 1971 - The Powell Memo