The

Congressional

Research

Institute

The greatest care should be employed in constituting this Representative Assembly. It should be in miniature, an exact portrait of the people at large. It should think, feel, reason, and act like them.John Adams 1776

Thoughts on Government

For Founding Father John Adams, a representative body should resemble a ‘portrait’ of the people. They should ‘think, feel, reason, and act’ like the people they represent. In other words, he believed that all representation should actually be inclusive. Since 2014, CRI has investigated ways to better accomplish his singular vision.

Based out of Cambridge, Massachusetts, CRI is an independent think tank focused exclusively on the problems of inclusive representation.

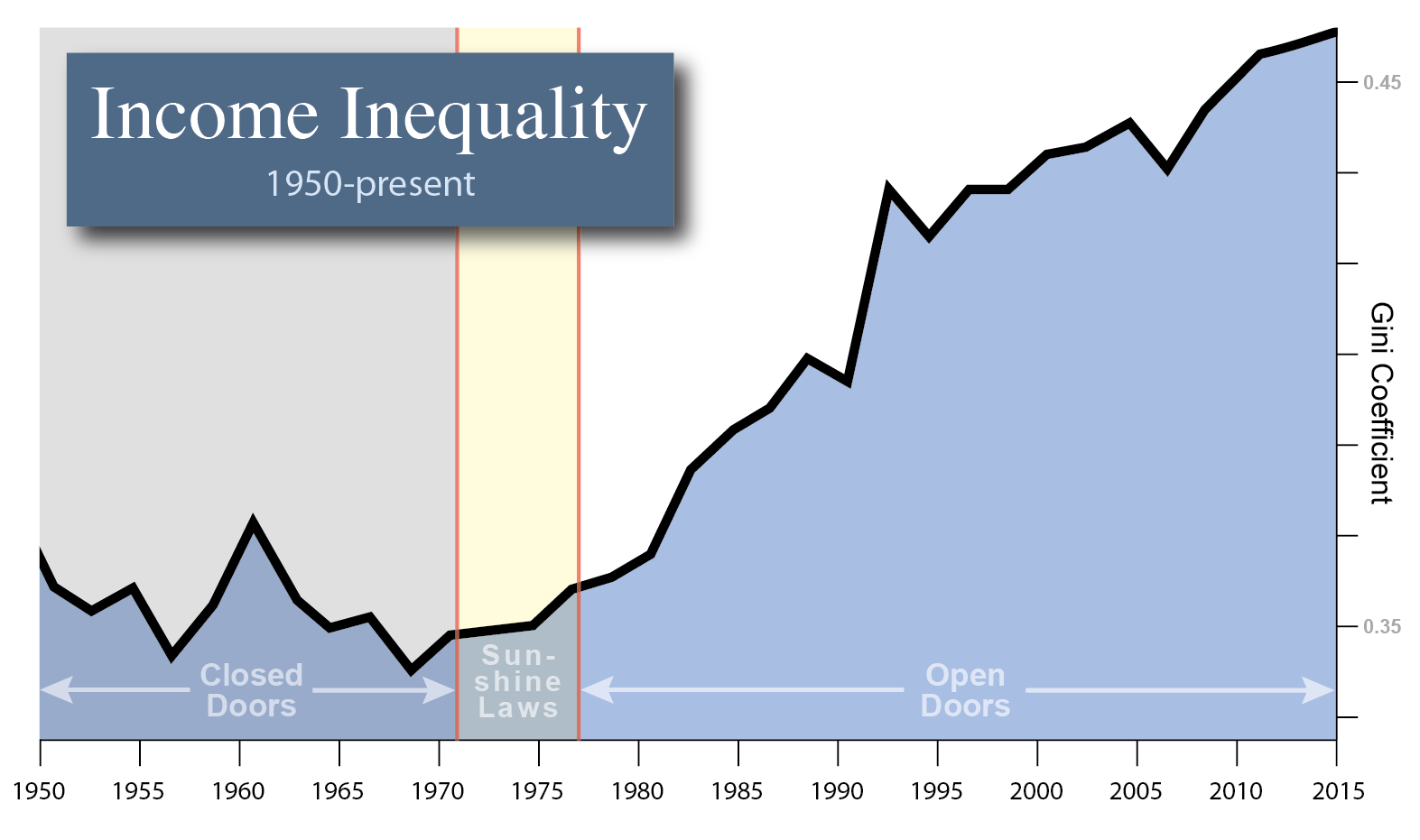

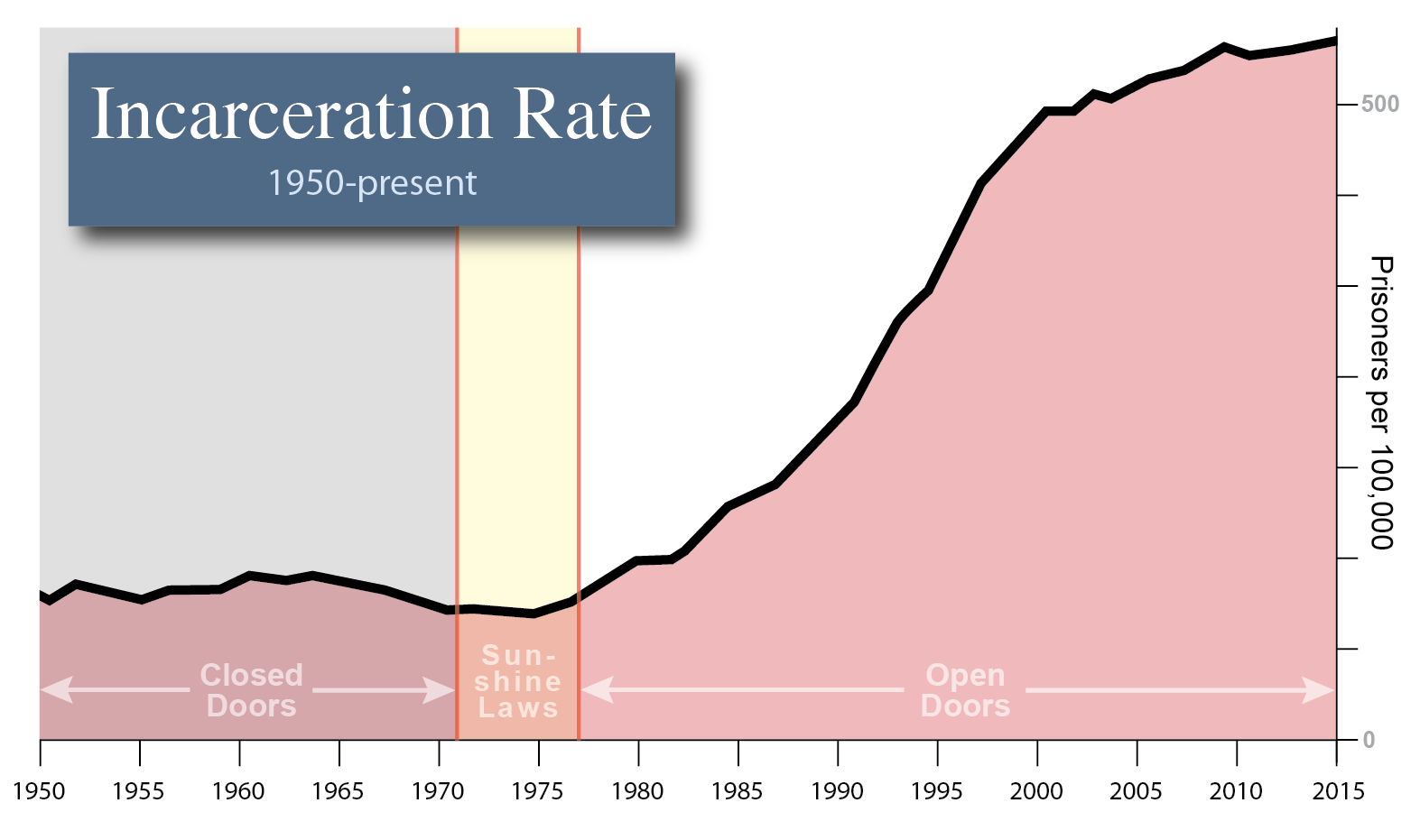

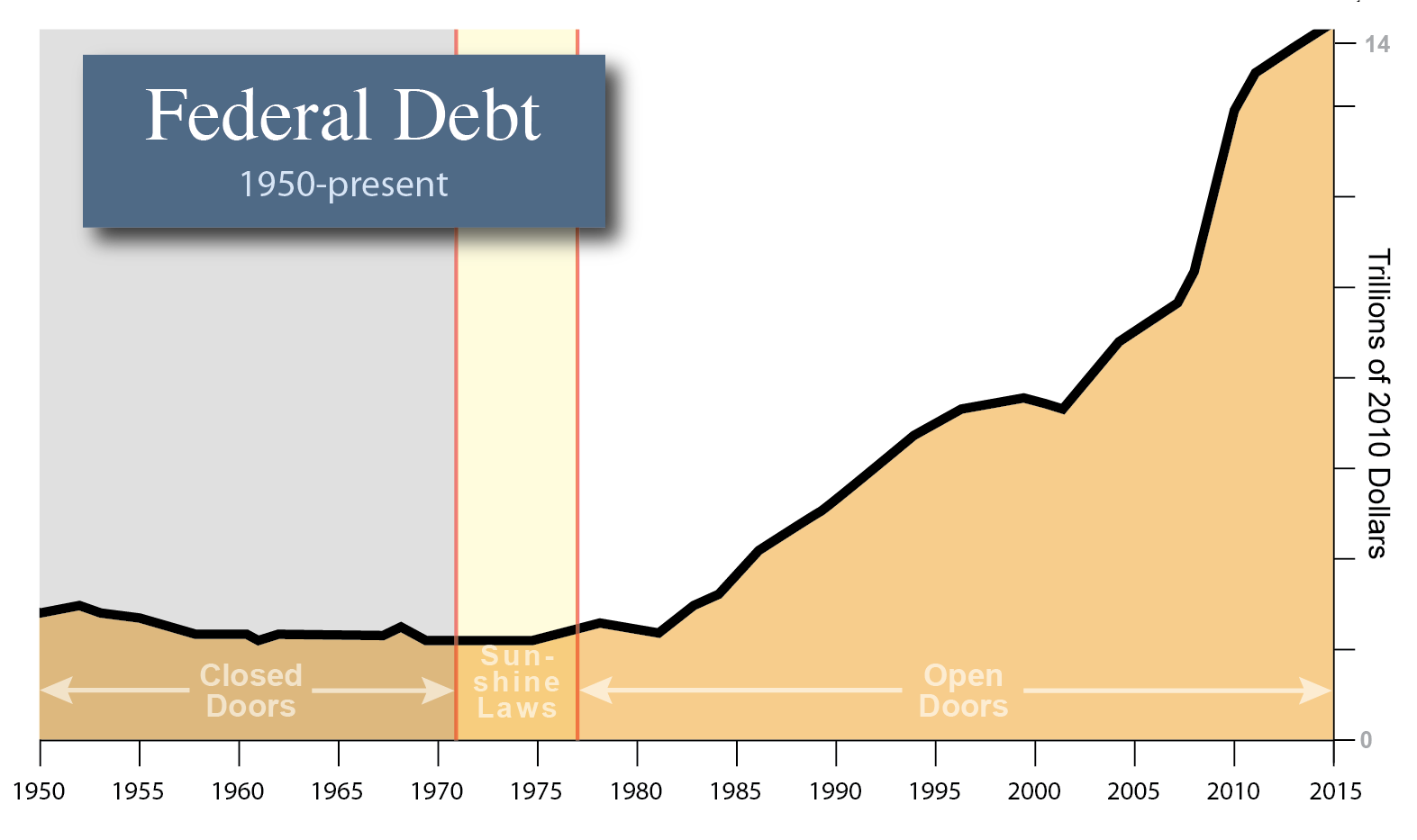

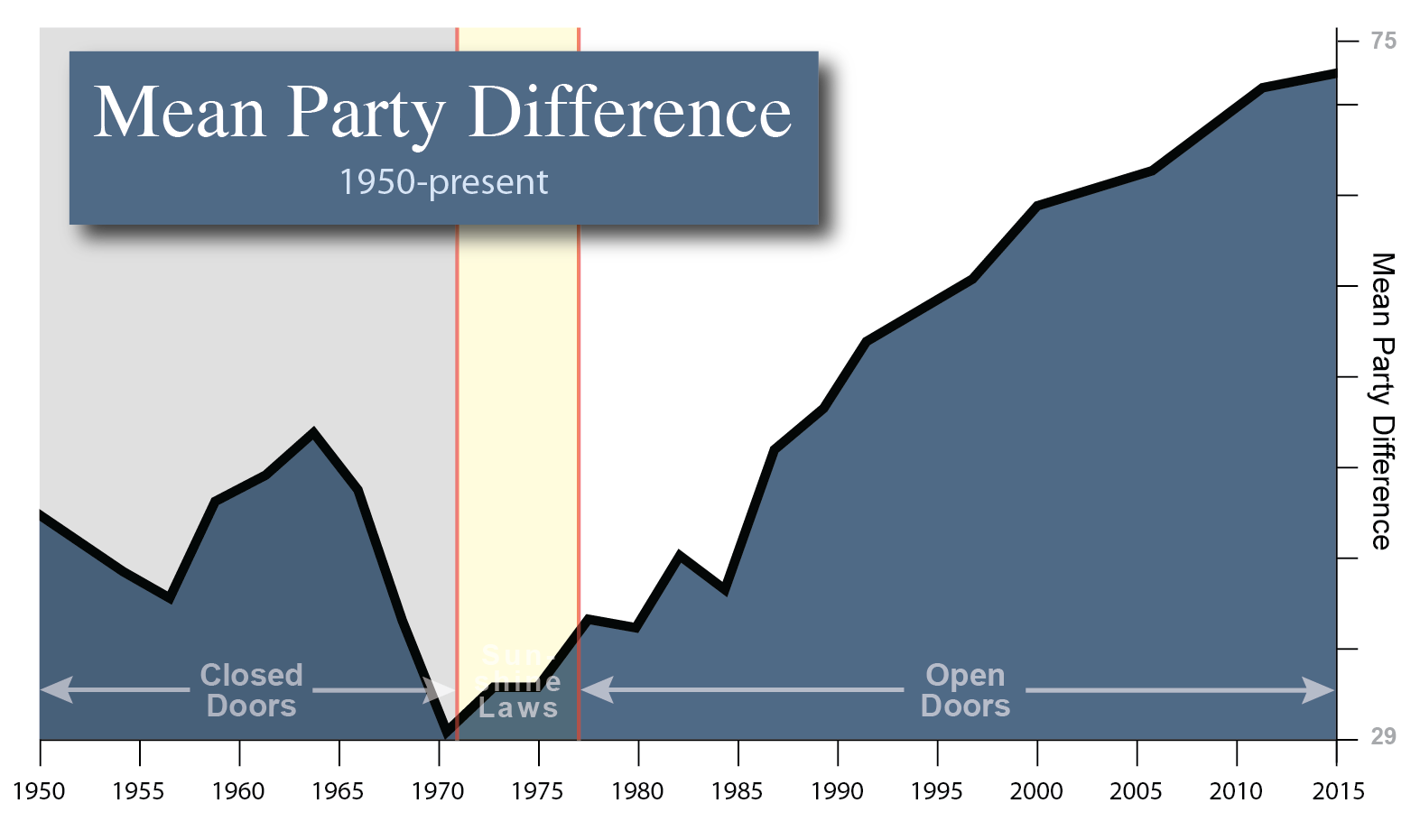

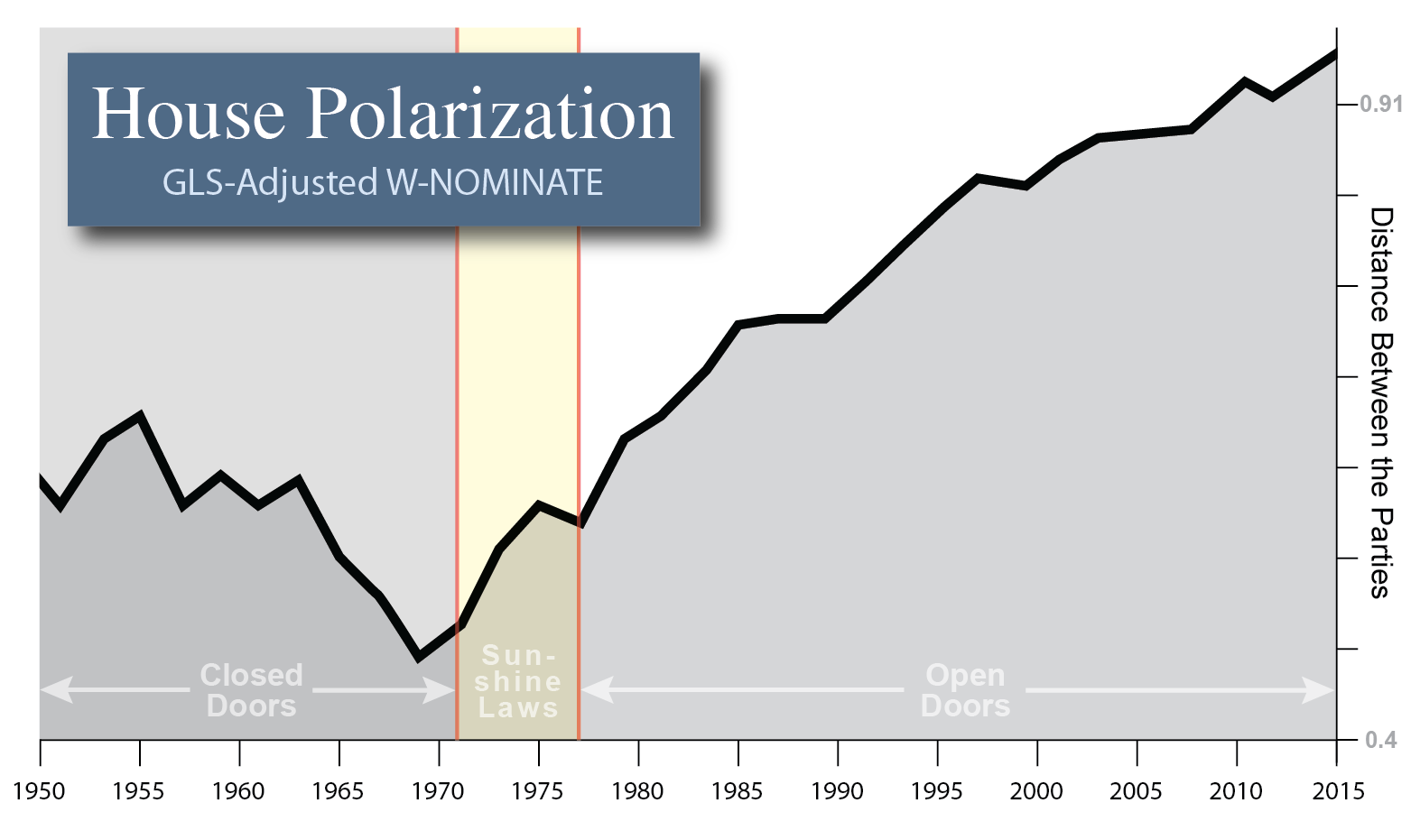

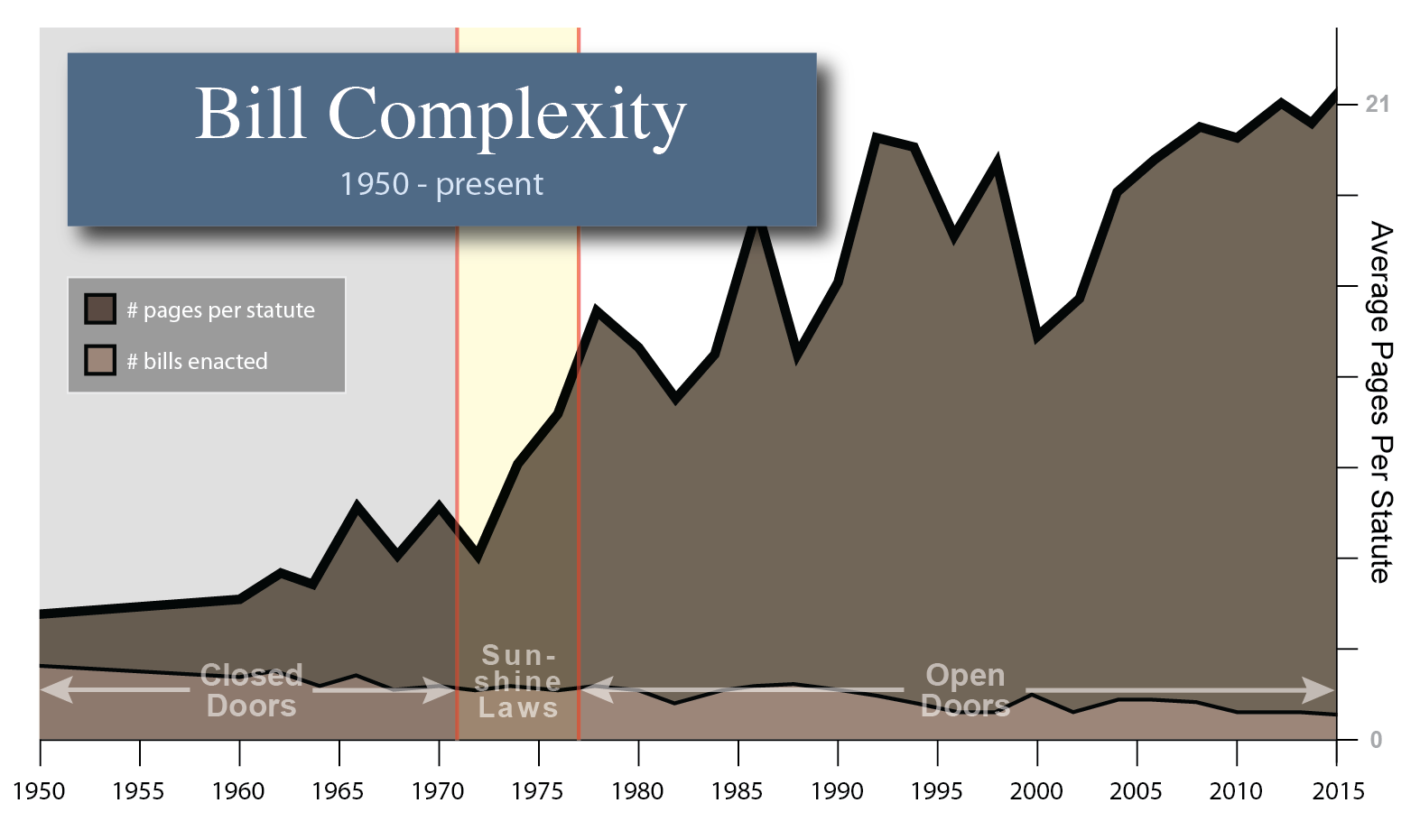

The principal researchers are Senior Lecturer in Public Policy, Harvard Kennedy School, David King, ex-NASA scientist James D’Angelo and Boston College professor Brent Ranalli. They are the first scholars to claim that the surge in 1970s sunshine (legislative transparency) is driving inequality, partisanship, spending, police immunity, climate change, incarceration, the debt, etc.

David King 2025 - Presenting the problems of transparency in Harvard Kennedy School

David King 2025 - Presenting the problems of transparency in Harvard Kennedy School

CRI published their work in Foreign Affairs in April 2019. The following May, Princeton scholar, Frances Lee presented their work in Congress, receiving an enthsiastic response from House members.

Recent Updates & Links

• Intro: Harvard Talk 2016: David King, Brent Ranalli and James D’Angelo discuss the pitfalls of congressional transparency and introduce the idea of weaponized transparency

• July 2020: CRI publishes an essay on the link between police immunity and transparency in Inequality Magazine

• June 2020: James D’Angelo & David King published an essay on the link between inequality and transparency in Inequality Magazine

• May 2020: CRI published a collection of citations on brubery (not bribery)

• April 2020: James D’Angelo presented a talk on the pitfalls of congressional transparency.

• July 2019: CRI publishes a widely circulated op-ed on weaponized transparency. Endoresed by Norm Ornstein and others.

• July 2019: CRI publishes an essay on the ties between legislative capacity and transparency in Leg Branch.

• May 2019: Brent Ranalli and James D’Angelo published an essay in Foreign Affairs Magazine describing the pitfalls of legislative transparency.

• September 2019: James D’Angelo spoke at the University of New Orleans.

• April 2019: James D’Angelo spoke at the Unrig Conference in Nashville in a panel moderated by Lawrence Lessig.

• December 2018: Brent Ranalli and James D’Angelo published scholarly article on the rise of lobbying viewed through the lens of increased transparency.

The Perils of Government Transparency

The core focus of CRI is an investigation into the pitfalls of increased transparency and accountability in legislatures, particularly the US Congress (see The Transparency Problem).

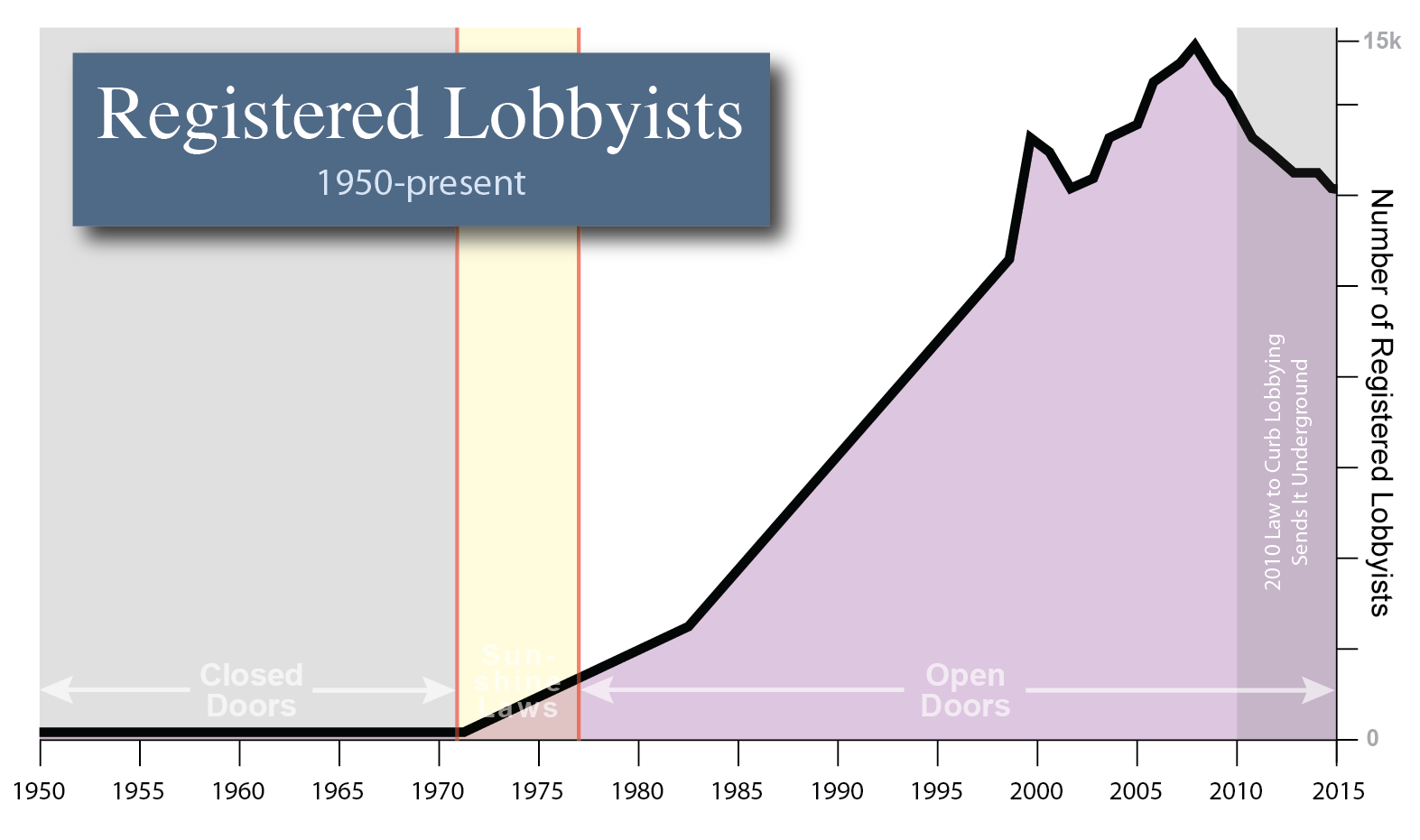

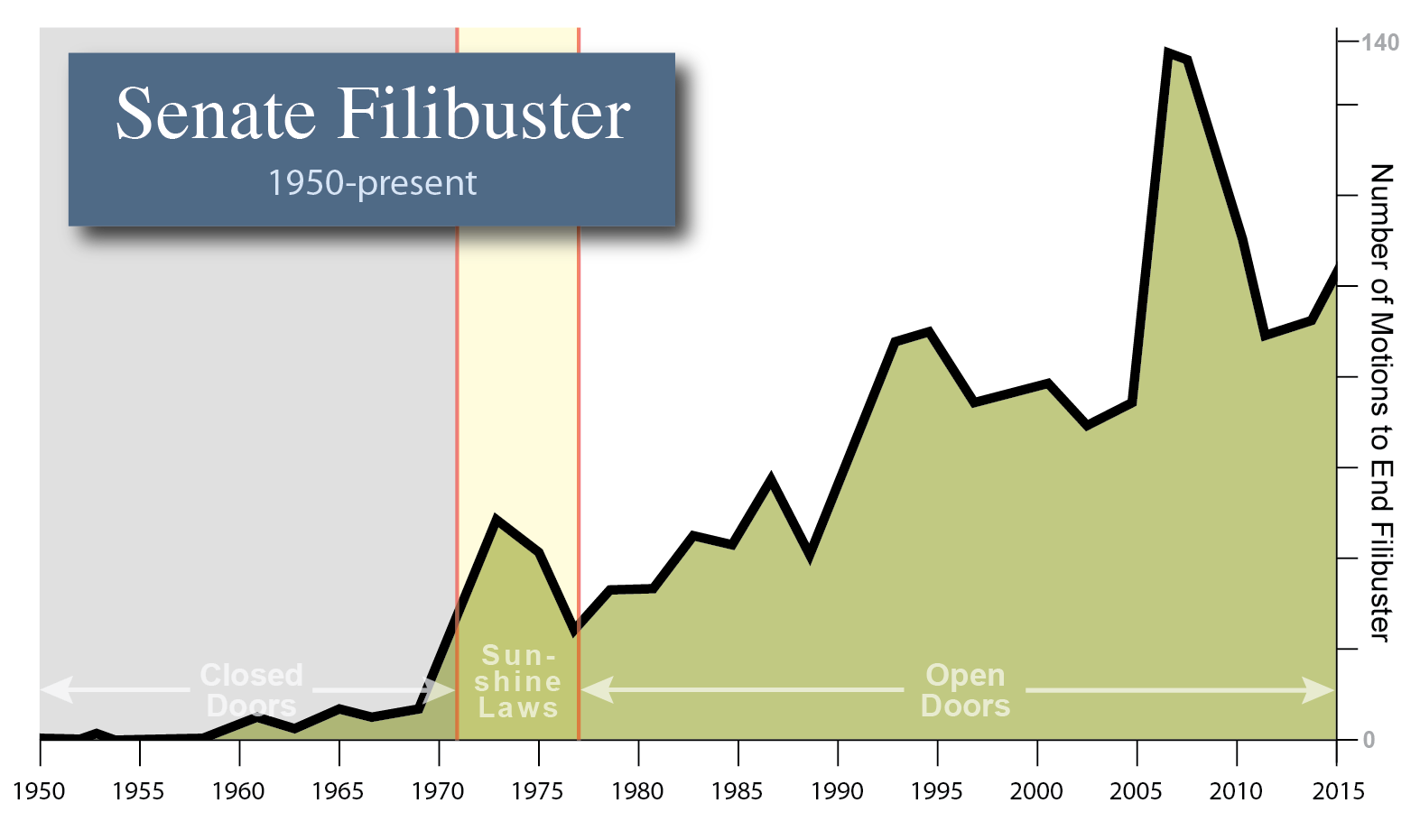

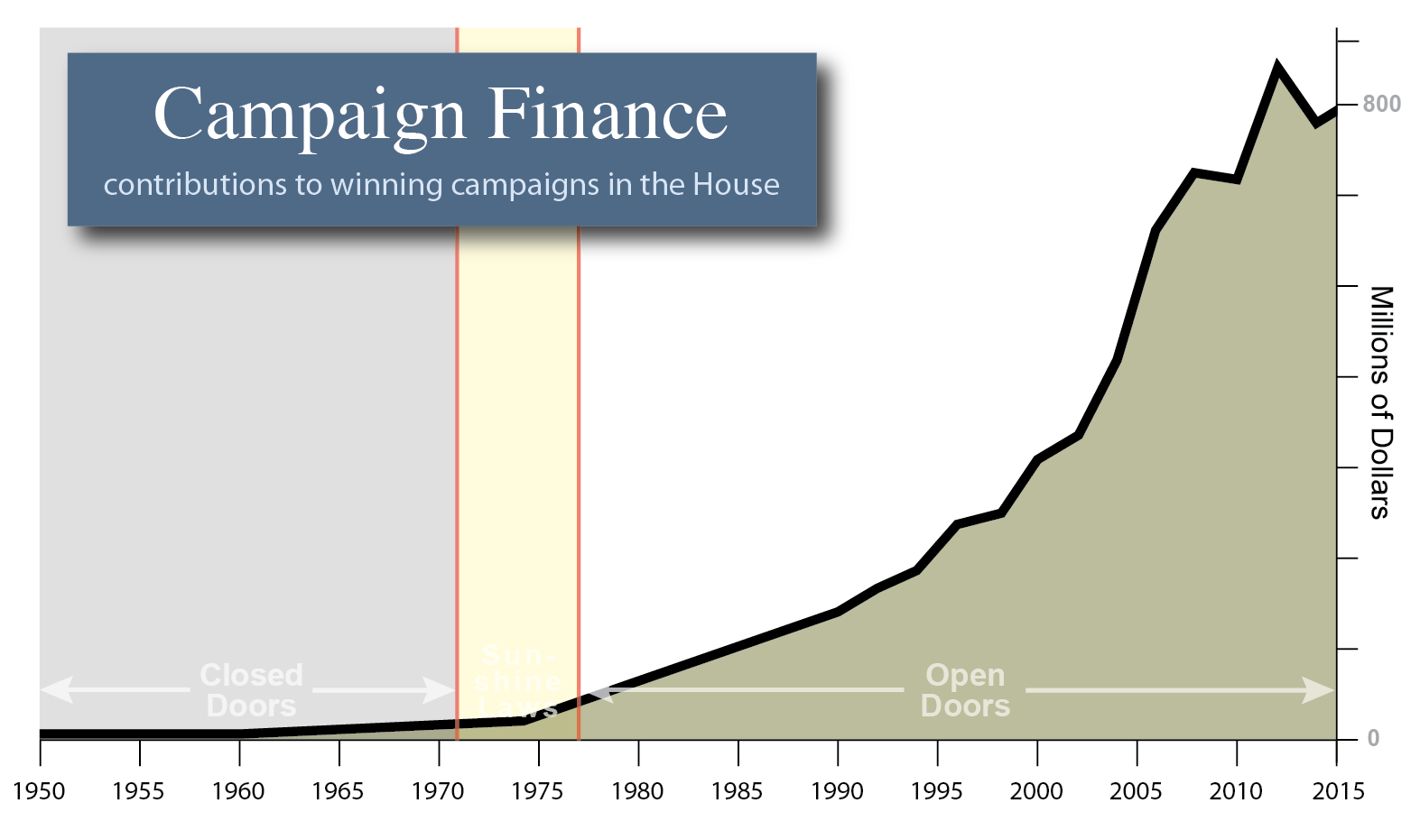

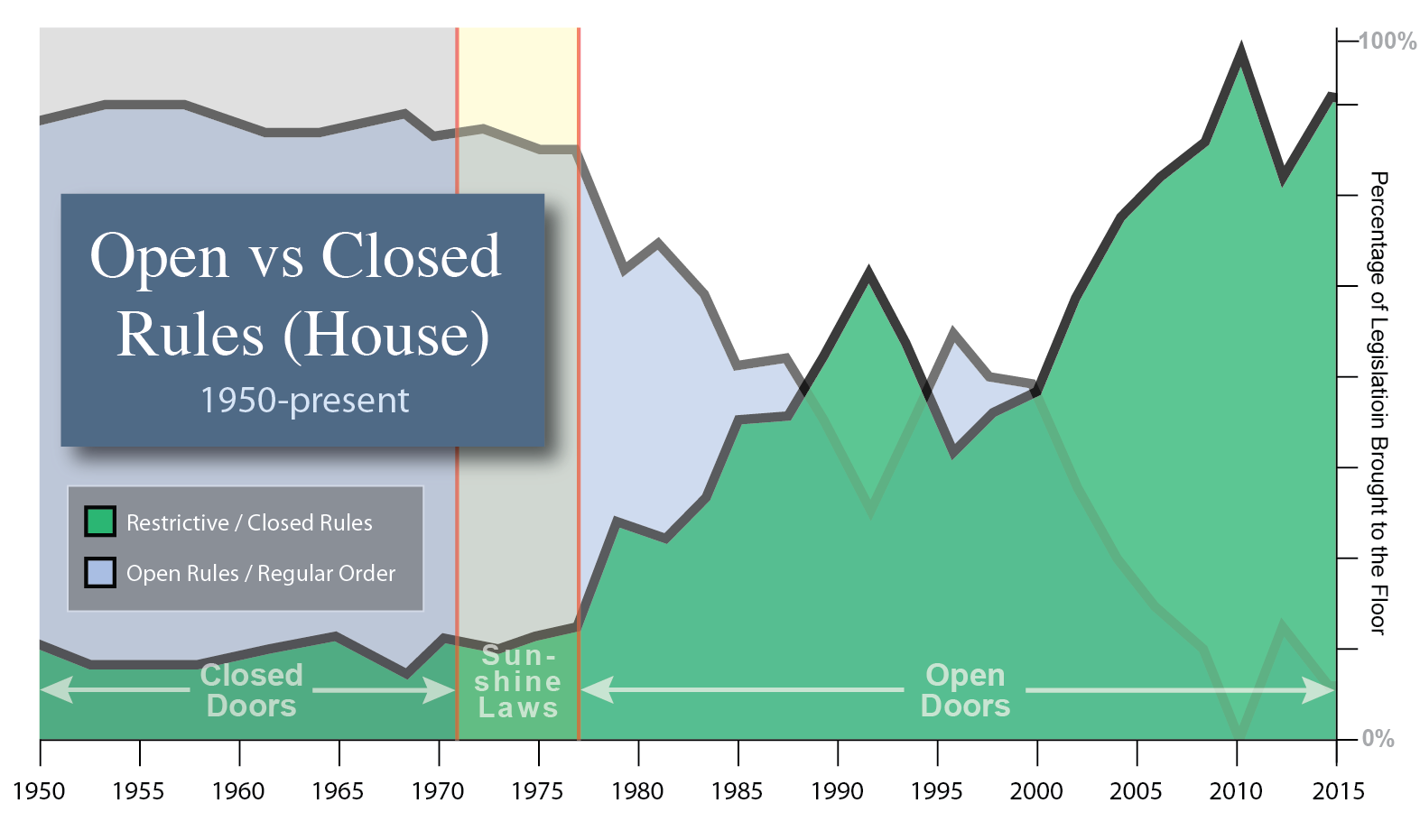

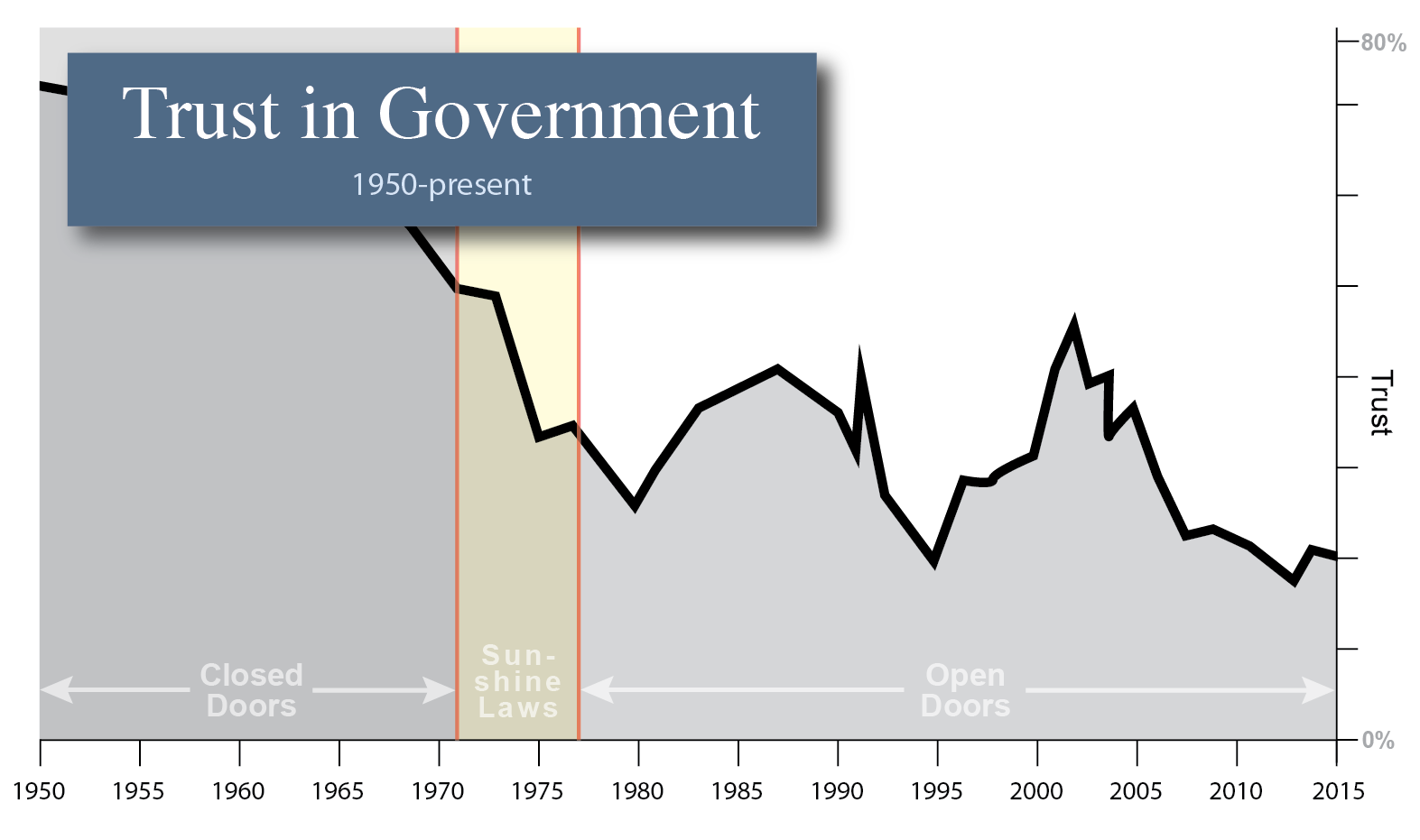

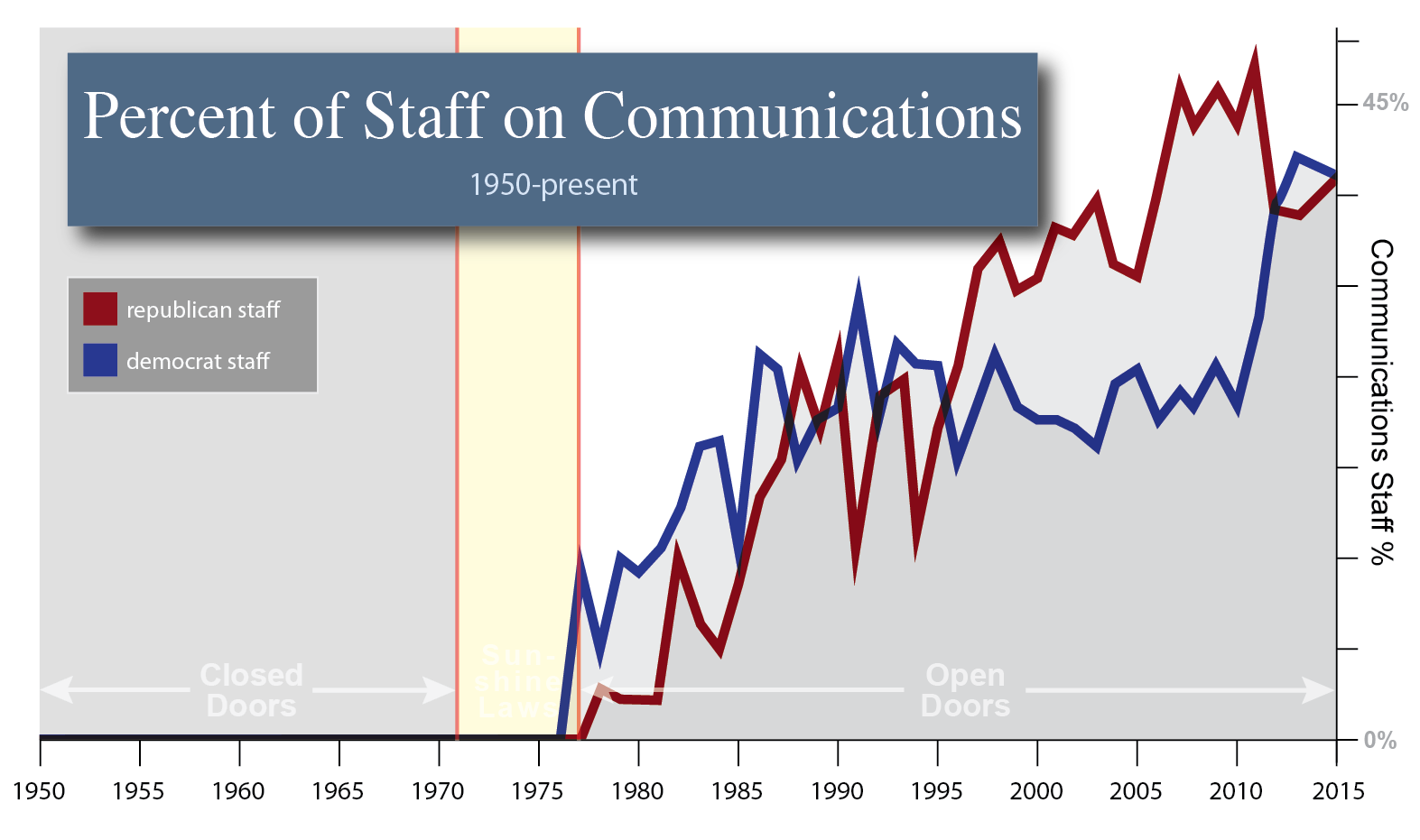

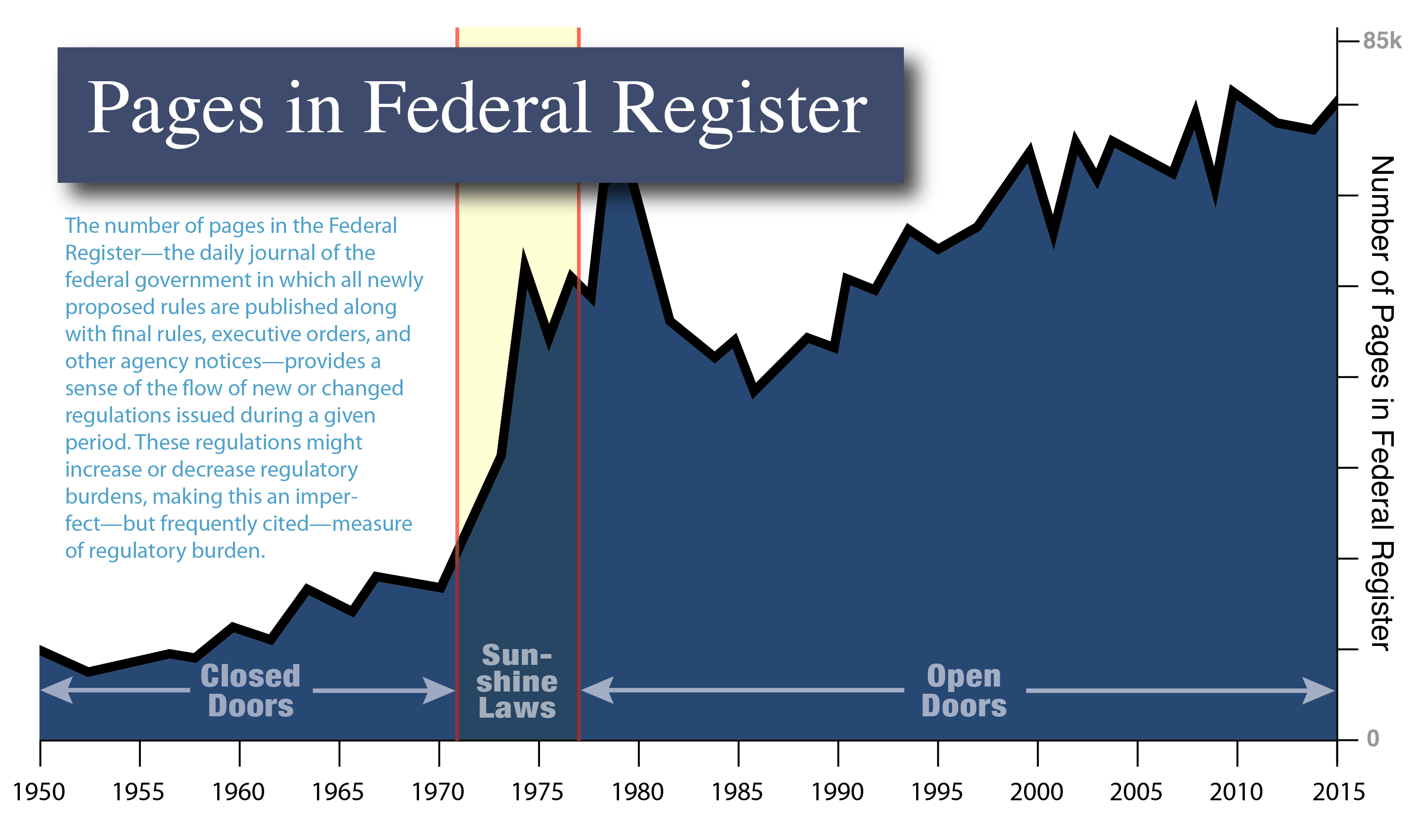

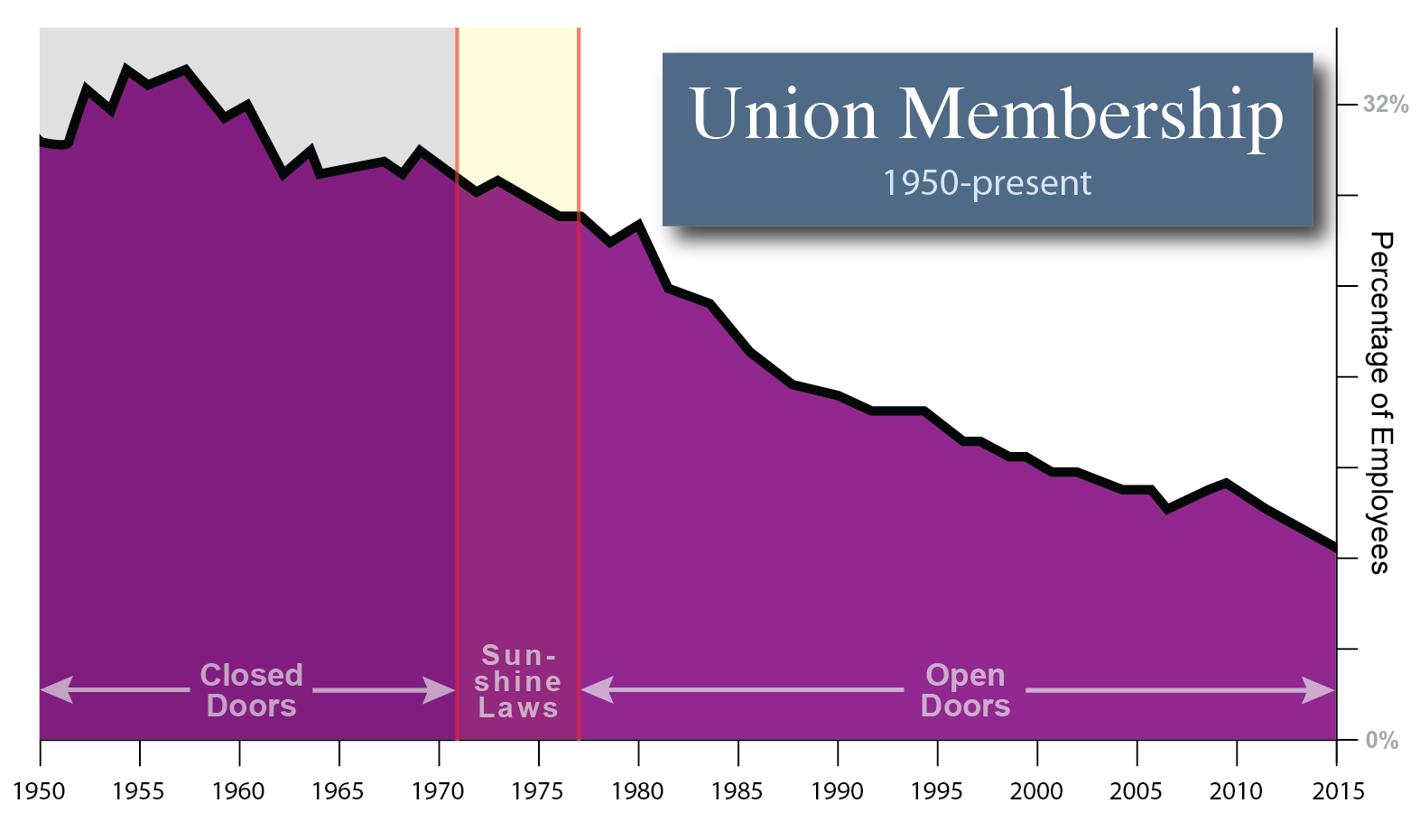

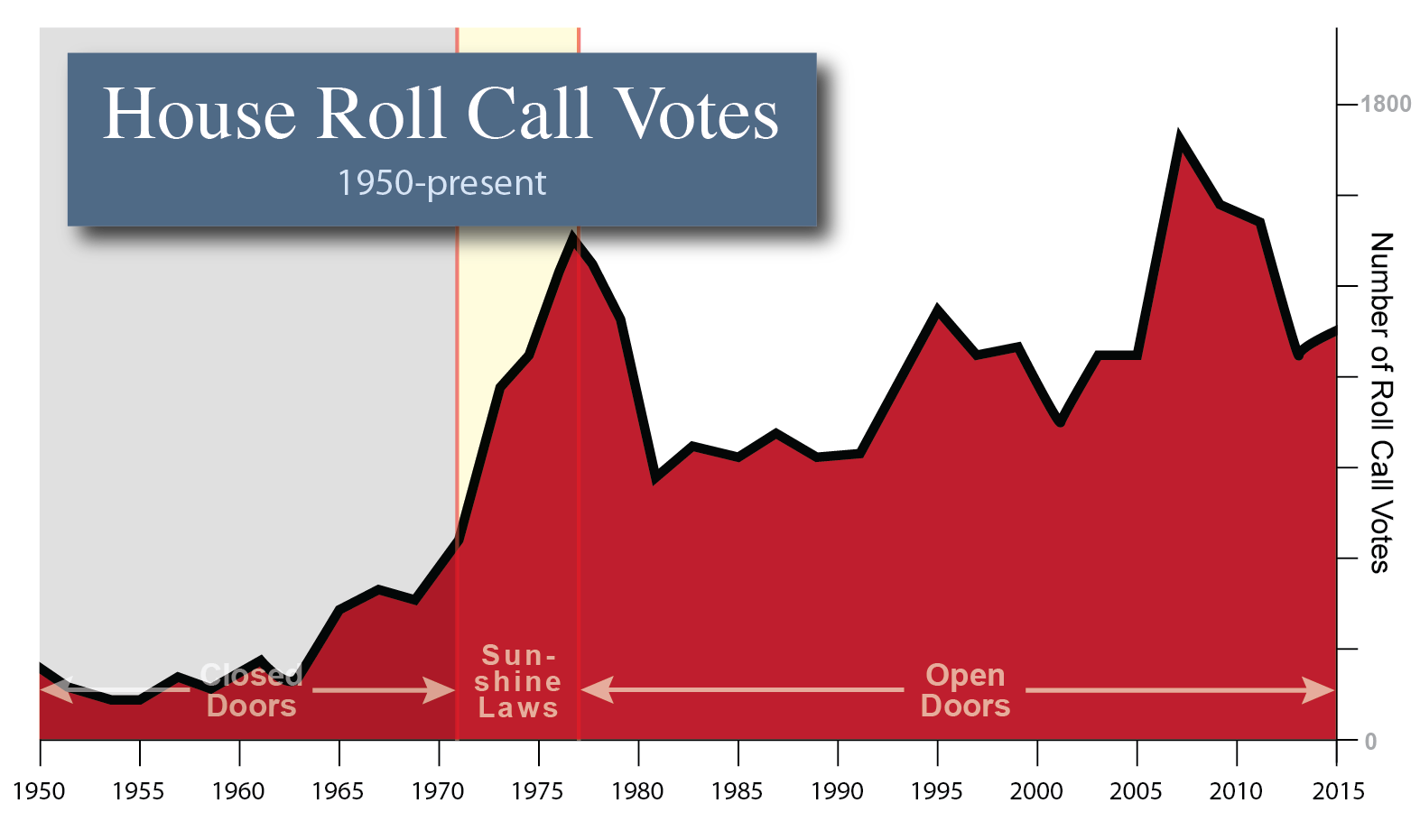

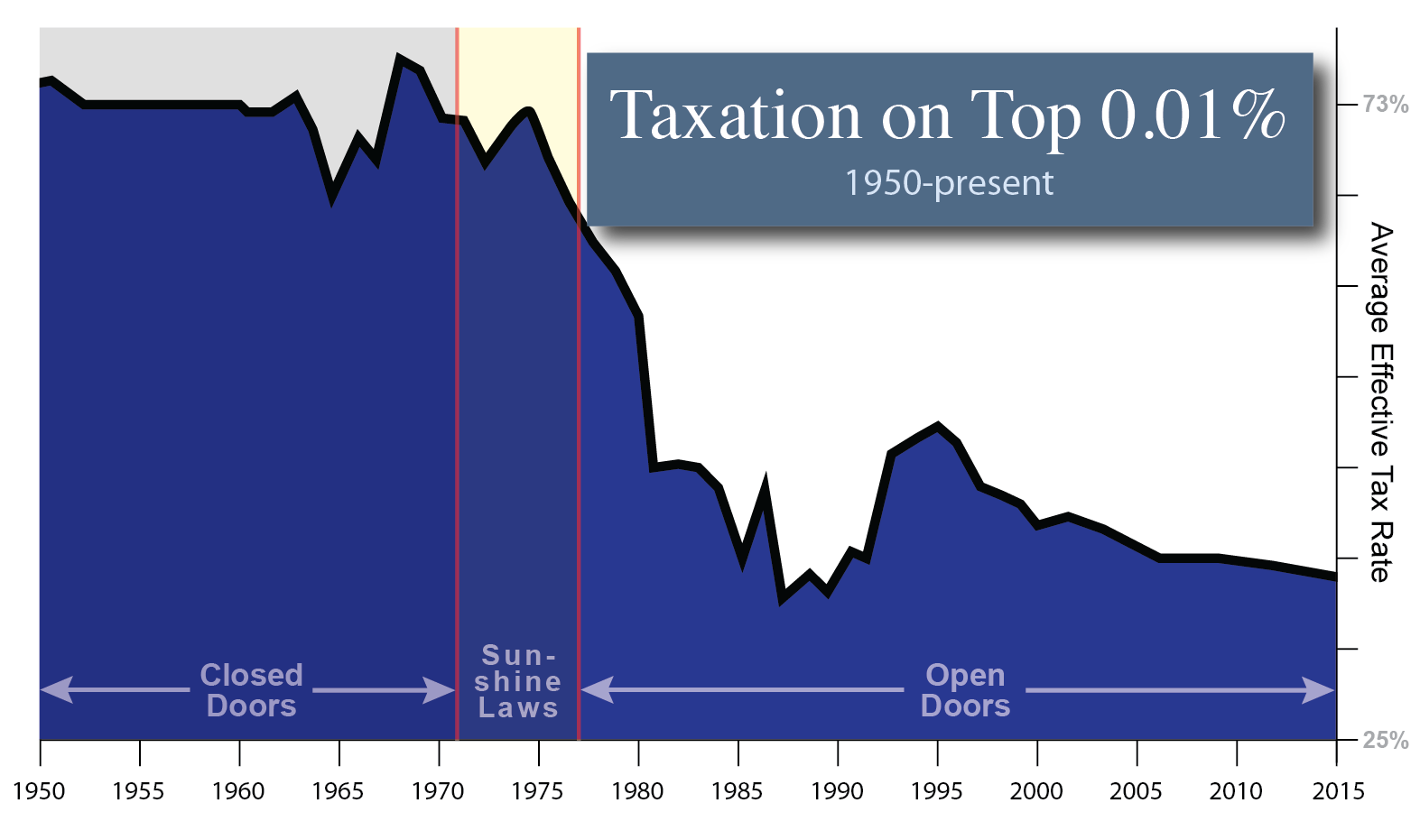

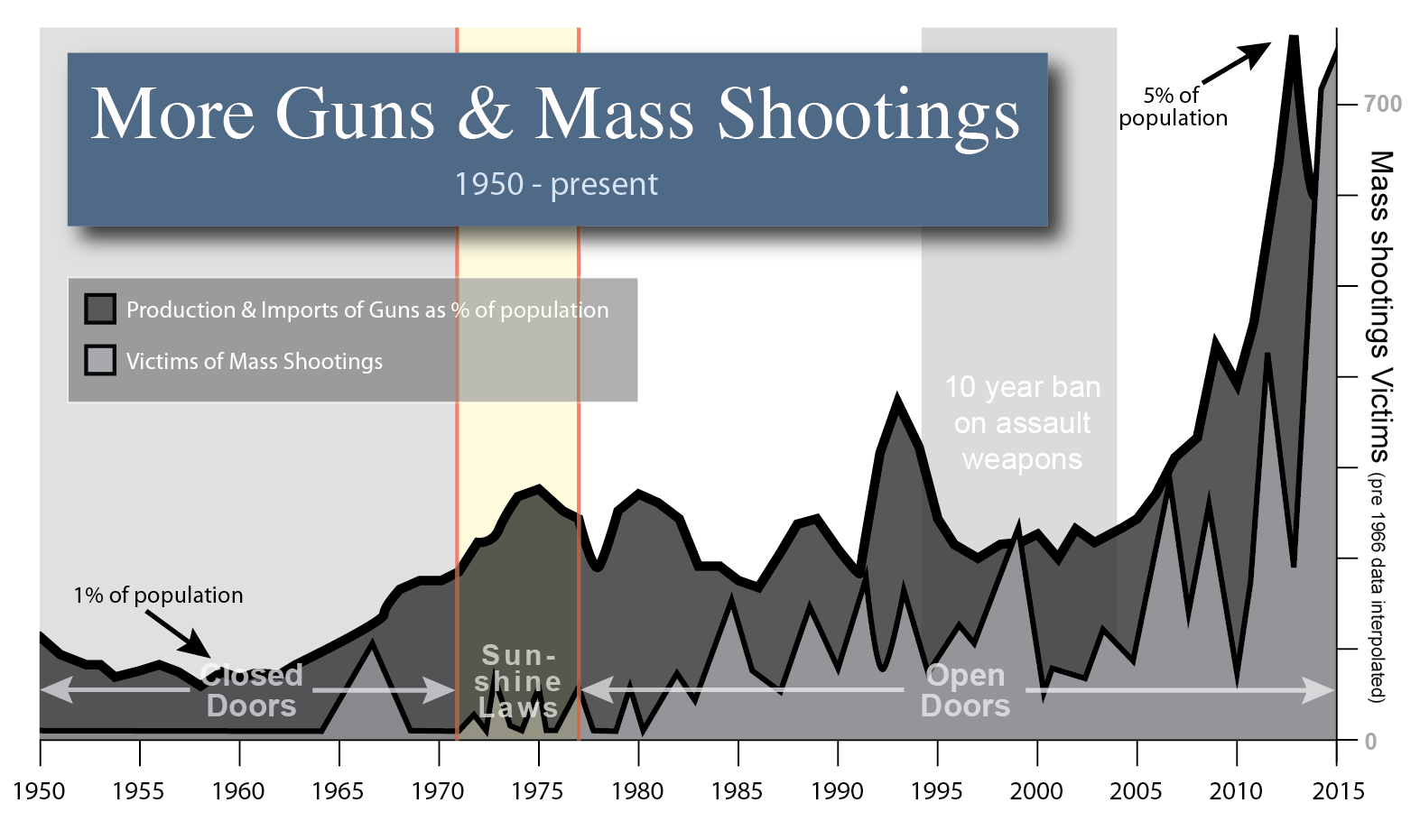

Surprisingly, this notion that transparency can degrade the quality of a democracy is something we are finding broad consensus on, with now more than 450 academic citations in support of this idea. The main point of increase in congressional transparency occured in 1971 via the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970. The 1970 LRA allowed outsiders (including lobbyists, the President and foreign companies), for the first time in history, to attend committee markup sessions and monitor the majority of committee votes.

This powerful increase in ‘sunshine’ provided a fundamental shift in the way Congress worked. For the previous two hundred years, dating back to the Constitutional Convention, these committee proceedings were conducted in secret as a way of avoiding the outside pressures (including lobbyists, Presidents, foreign entities and even, as JFK suggested

, the people). But with the LRA, signed by President Nixon on October 26th, 1970, the floodgates were opened.

Consistent with the theory, this vast increase in transparency dramatically changed the intra-member dynamics of lawmaking and enormously enhanced the ability of ‘outside’ lobbyists and powerful entities to influence the legislative process. This work has culminated in our claim that all legislative transparency overwhelmingly benefits special interests and the powerful. Further, reform ideas based on increased accountability and transparency are based on myths and function in the exact opposite way of how they are intended to work. This has seismic repercussions on our understanding of accountability, transparency and representative democracy. And one of our core conclusions for improving American democracy is that we need to, once again, relegate the lobbyists to the lobby – giving them no access to markup sessions and no access to committee votes. Further, by increasing the amount of secrecy and privacy for legislators, and thus protecting them even from eachother, we will indeed be increasing the quality of our democracy.

Designing Inclusive Representation

A CRI we are working on two other research projects as well, both related to the question of representation. In particular, these ideas focus on the skewed representative make up of real world legislative bodies, both in the areas of wealth (see The Representative Ratio) and minority makeup (see The Senate Problem). As such we have proposed a new metric for democracies called the Representative Ratio (RR) which we expect will not only help in analyzing world democracies but may likely lead to solutions, as many developing countries have an RR that exceeds 1,000 and correlates strongly with institutional corruption and inequality.

Finally, by changing the way Americans vote for their Senators (and likely for members of the House as well), we can not only eliminate gerrymandering but also significantly increase the voice of all minorities, both political and racial.

Democracies Should Abhor Inequalities

In theory, democracy is a bulwark against socially harmful policies, but in practice it gives them a safe harbor.Bryan Caplan 2006

Paradox of Democracy

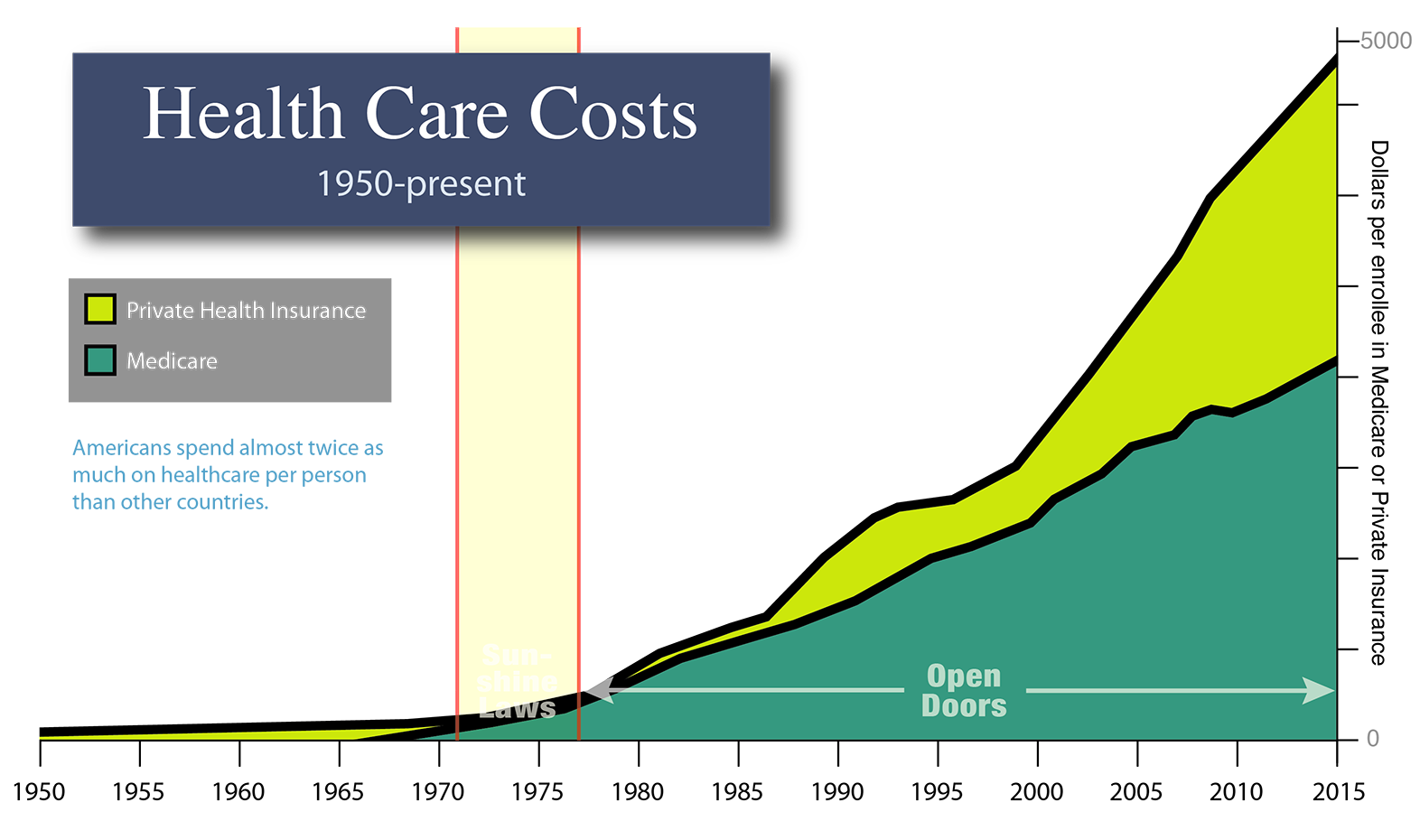

A democracy should abhor inequality. Through voting, the impoverished masses should have near absolute control over the rules of the economy. They should control the redistribution of wealth, the rules of trade, health care, labor etc. But while democracies have produced many of the most egalitarian economies in history, their record is far from perfect. Indeed, this theoretical hegemony of the poor often appears as just an illusion, or worse, non-existent. When this occurs, however, we are convinced that this is a problem with representation and democracy, and our mission at CRI is to address this problem at its root.

The notion that inequality should be at least partially self-correcting in a democracy has a long pedigree in economic theory. In the canonical model of Meltzer and Richard, increased inequality leads the median voter to demand more redistribution.Bonica, McCarty, Poole & Rosenthal 2013

Why Hasn’t Democracy Slowed Rising Inequality?

Ironically, however, when wealth inequality shoots up and destabilizes (as it has over the past fifty years in the United States) the media turns almost exclusively to economists for answers. It is a bit like calling in a tailor to solve a problem with obesity. Sure, a good suit may make the patient look and feel better, but it doesn't address the underlying problem. Democratic governments, through voting, have provided the only occasional check on the accumulation of power in history. And government, not an invisible hand, defines the rules of the economy. And so, while inequality might appear to be a problem for economists (who readily write books on the subject), it is more accurately a problem of the institutions of democracy.

We believe that legislatures can and should reflect the will of the people. As Adams said, a representative assembly should “be in miniature, an exact portrait of the people at large.” This is our goal. And we believe that this can be accomplished only by investigating and improving the design of the only institution that has ever put a check on power – democracy.