250+ Academic Citations

Constituents Do Not Monitor Congress, Lobbyists Do.

Throughout history, the engagement of citizens in the political process has been a chimera. In developed countries, national legislators vote over 1,000 times each year. Their decisions are based on millions of pages of bills, proposals, amendments, hearing transcripts, debates, legislation, executive memos, staff reports, constituent mail, lobbyist activity etc. Further the language is inordinately complex and often so opaque that few can understand the significance. Because of this scholars have suggested that it could be impossible for even the most active citizens (or even a full-time professor of government) to actively monitor the legislative process. This argument appears to hold even if citizens were to limit their focus to just single topics or single legislators. Even beyond legislatures the general argument applies, as constituents rarely follow any aspect of government in detail. More importantly, all studies - across all time periods - appear to confirm these claims.

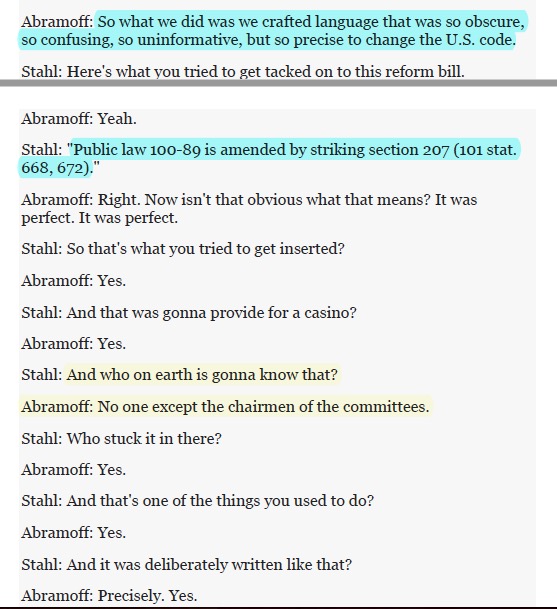

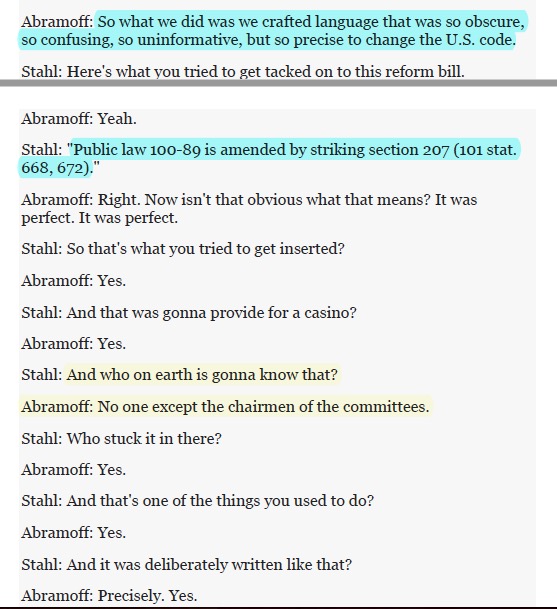

In the United States, this situation is exacerbated by the fact that lobbyists can and do follow legislation. Well-paid lobbyists are issue specialists. Many have spent decades following single issues on the Hill as staffers, reporters, etc. and have been intensely involved in drafting and crafting such legislation. Unlike the vast majority of the population, these (often masters degree) legal-experts / guns-for-hire readily follow legislation in specific fields and understand the consequences these policy proposals. These lobbyists then report their findings to their employers (often wealthy groups). Once informed, these wealthy groups go to work, usually intimidating the legislators involved, forcing compliance. Thus, the pervasive ignorance of the voter is made worse by the intricate knowledge of policy by wealthy interests.

By James D’Angelo & Brent Ranalli – November 28, 2025

Major Studies

Research to support the idea that citizens do not monitor legislation or government.

Pew Research 2011

Pew Research 2011

Pew Research 2007

Pew Research 2007

Intercollegiate Studies Institute

Intercollegiate Studies Institute

Annenberg Public Policy 2010

Annenberg Public Policy 2010

Ipsos Mori 2014

Ipsos Mori 2014

Citations

Here we present a collection of studies, citations and sources to support the notion that citizens do not (and likely cannot) monitor the legislative process. As a result popular democratizing or direct democracy reforms pushed by groups like the Sunlight Foundation, Transparency International, GovTrack.org or Represent.Us are likely based on dangerously flawed, ‘pigs-fly’ type assumptions. Worse, despite our queries, these groups have provided no data to suggest the contrary - either that citizens do monitor government or that transparency of the legislative process confers benefits to citizens. Central to this problem are misconceived notions of accountability.

By anything approaching elite standards, most citizens think and know jaw-droppingly little about politics.Robert Luskin 2002

Politics and Identity

The political ignorance of the American voter is one of the best-documented features of contemporary politics.Larry Bartels 1996

Uninformed Votes

The number of people who understand the tax bill, rounded to the closest number, probably is zero. Zero percent.Matt Glassman 2017

Spending Bill and Speaker Ryan’s Future

Congress is not well understood by the average citizen.Walter Oleszek 2011

A Perspective On Secrecy and Transparency

Noam Chomsky 2020 - Twitter Profile

Noam Chomsky 2020 - Twitter Profile

While we certainly do not take the American public as fools, they simply are not knowledgeable enough about the congressional process to understand the partisan maneuvering.David Rohde 2012

Party and Procedure in the United States Congress

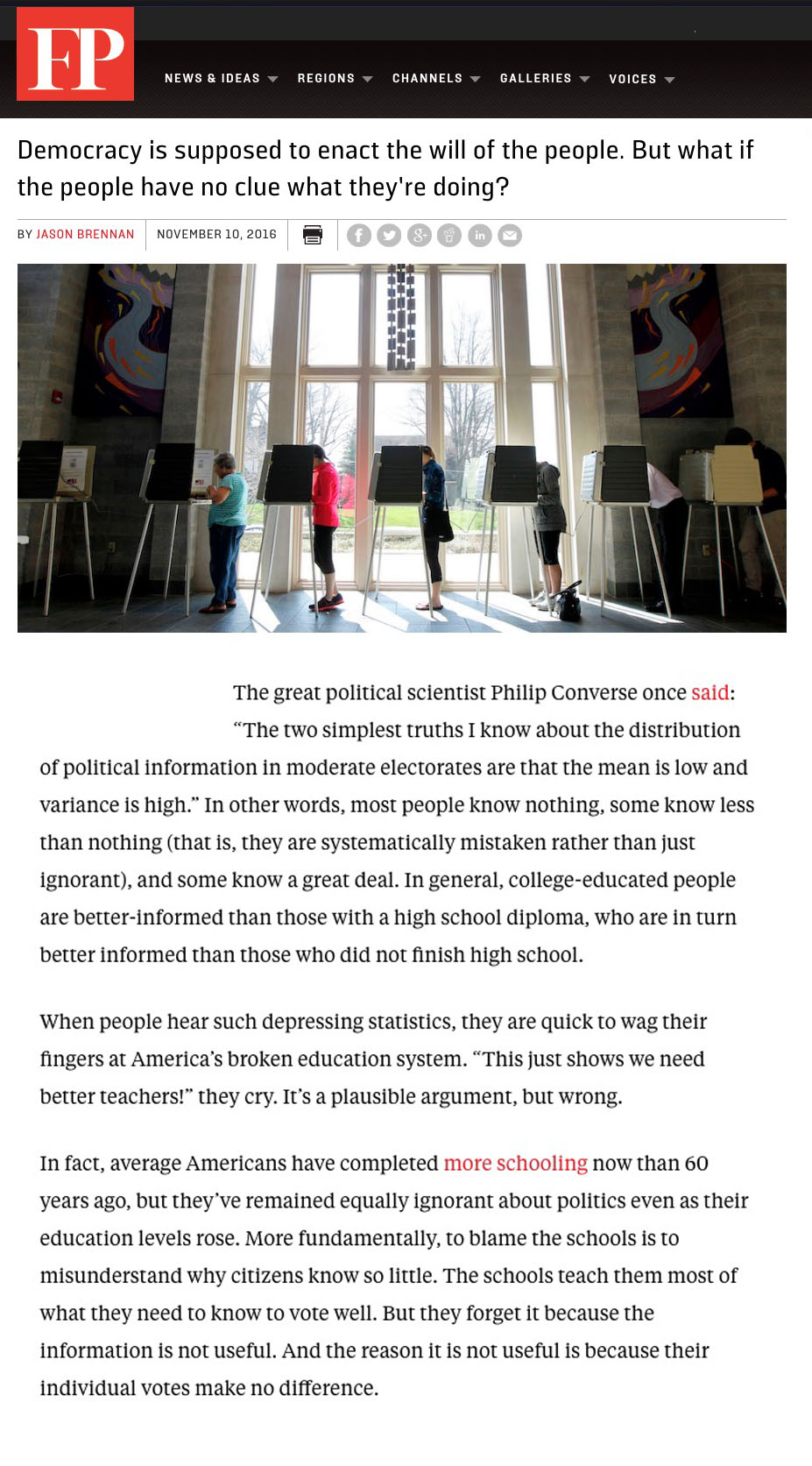

Voters in most countries can identify the incumbent chief executive, but know little else beyond that.Jason Brennan 2016

Against Democracy

The fewer the number of taxpayers affected, and the more dull and arcane the subject, the longer the line of lobbyists.Rep Pete Stark 1988

Showdown at Gucci Gulch

Jill Lepore 2012 - Story of America

Text: Pop quiz, from a test administered by the Hearst Corporation in 1987, during the Constitution’s bicentennial: True or False: The following phrases are found in the U.S. Constitution: “From each according to his ability, to each according to his need.” “The consent of the governed.” “Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” “All men are created equal” “Of the people, by the people, for the people.”42 This is what’s known as a trick question. None of these phrases are in the Constitution. Eight in ten Americans believed “all men are created equal” to be in the Constitution. Even more thought that “of the people, by the people, for the people” was in the Constitution. Abraham Lincoln, Gettysburg, 1863. Nearly five in ten thought “from each according to his ability, to each according to his need,” was written in Philadelphia in 1787. Karl Marx, 1875.43 Something between a quarter and a third of American voters are what political scientists call, impoliticly, “know nothings,” meaning that they possess almost no general knowledge of the workings of government, at least according to studies conducted by the American National Election Survey (ANES).44 This problem is said to be intractable. The know-nothing rate just won’t budge; it’s been about the same since the Second World War.

Jill Lepore 2012 - Story of America

If six decades of modern public opinion research establish anything, it is that the general public’s political ignorance is appalling by any standard.Bruce Ackerman & James Fishkin 2004

Deliberation Day

Mass ignorance is the most obvious cause behind the foolishness that marks so much of American politics.Rick Shenkman 2008

Just How Stupid Are We?

The typical citizen drops down to a lower level of mental performance as soon as he enters the political field. He argues and analyzes in a way which he would readily recognize as infantile within the sphere of his real interests. He becomes a primitive again.Joseph Schumpeter 1942

Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy

Arthur Lupia 2014 - Uninformed

Arthur Lupia 2014 - Uninformed

It’s odd that while citizens regularly criticize their lawmakers for being dishonest and not following through on campaign promises, surveys routinely show that many citizens don’t know who their representative is in the first place (let alone know their position on key votes).Tracy Sulkin 2013

Promises Made, Promises Kept

The unhappy truth is that the prevailing public opinion has been destructively wrong at the critical junctures. The people have imposed a veto upon the judgments of informed and responsible officials. They have compelled the governments, which usually knew what would have been wiser… Mass opinion has acquired mounting power in this century. It has shown itself to be a dangerous master.Walter Lippman 1955

Essays in Public Philosophy

Citizens on average do not have the time, expertise, resources, and interest to make the many decisions required in contemporary governance.Bruce Cain 2014

Democracy - More or Less

Walter Lippman 1927 - The Causes of Political Indifference

Walter Lippman 1927 - The Causes of Political Indifference

The great body of the people are without virtue and are not governed by any internal restraints of conscience.Rufus King 1787

Constitutional Convention

Political science tells us that the most American citizens neither know, nor care about their political representatives and the policies of their government, and the most importantly, these findings are common knowledge among students of politics.Michael Margolis 1983

Democracy: American Style

The people do not take any great offense at being kept out of the government – indeed they are rather pleased than otherwise at having leisure for their private business.Aristotle 350 BC

Politics

Frederic Charles Schaffer 2002 - Clean Elections and the Great Unwashed

Frederic Charles Schaffer 2002 - Clean Elections and the Great Unwashed

We don’t see strong citizen concern about climate if we look at citizen action. They drive SUVs, live in enormously polluting houses, dispose of plastic bottles. To argue that citizens care and act accordingly is out of step with the data.James D’Angelo 2019

Unrig Summit Nashville

Public opinion research shows us that the public will very often provide majority support for a policy proposal and, simultaneously, provide majority opposition to that same proposal.Richard Longoria 2018

Janus Democracy

When voters endure natural disasters they generally vote against the party in power, even if the government could not possibly have prevented the problem.Christopher Achen & Larry Bartels 2016

Democracy for Realists

The public’s ignorance of political matters has been repeatedly confirmed ever since randomized opinion surveys began in the mid-twentieth century. In 1964, at the height of the Cold War, only 38 per cent of the American public knew that Russia was not a member of NATO. In 1979, only 24 per cent of the public could summarize the First Amendment. In 1989, only 57 per cent of the public knew what a recession was.Jeffrey Friedman 2013

Political Knowledge

Diana Thomas 2013 - Why Are Voters So Uninformed?

Diana Thomas 2013 - Why Are Voters So Uninformed?

A great vice in most ancient republics was that the people had the right to make resolutions for action, resolutions which required some execution, which altogether exceeds the people’s capacity. The people should not enter the government except to choose their representatives; this is quite within their reach.Montesquieu 1748

Spirit of the Laws

Democratic publics are not in fact able by background or temperament to make large numbers of complex public policy choices; what has filled the void are well-organized groups of activists who are unrepresentative of the public as a whole. The obvious solution to this problem would be to roll back some of the would-be democratizing reforms, but no one dares suggest that what the country needs is a bit less participation and transparency.Francis Fukuyama 2014

Political Order and Political Decay

Decades of political science research should have undermined any naive faith in citizen capacity and made us aware that pluralist realities often overtake populist idealsFrancis Fukuyama 2015

The Limits of Transparency

Party and machine politics are simply the response to the fact that the electoral mass is incapable of action other than a stampede.Joseph Schumpeter 1943

Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy

George Lakoff 2012 - Dumb and Dumber

George Lakoff 2012 - Dumb and Dumber

“People in the mass are unconcerned about details,” NIIC spokesmen have assured the NAM in convention assembled. “They tend to think in blurs. They are moved primarily by simple, emotional ideas. The NIIC will capitalize upon this fact with an aggressive program designed to inspire a crusade that will sweep free enterprise into public favor.”Stetson Kennedy 1946

Southern Exposure

Political scientists are repeatedly astonished by the shallowness and incoherence of people’s political beliefs, and by the tenuous connection of their preferences to their votes and to the behavior of their representatives. Most voters are ignorant not just of current policy options but of basic facts, such as what the major branches of government are, who the United States fought in World War II, and which countries have used nuclear weapons.Steven Pinker 2018

Enlightenment Now

Since incumbents characteristically win reelection, constituents may usually be unable to sanction congressmen at the polls for votes which are out of keeping with their wishes. The fact that voters know so little about their congressman's record, furthermore, can be said to indicate that they normally do not control his behavior. Since the congressman rarely receives any kind of specific constituency guidance on how to cast a particular vote, another argument runs, he must fall back on his own devices and is left quite free to decide as he chooses.John Kingdon 1989

Congressmen’s Voting Decisions

Politicians and pundits like to think that the voters are as conscious of political issues and tactics as the experts are, but the real America is an apolitical country whose citizens mostly participate – or don’t – in politics every two or four years on election day.Robert Kaiser 2009

So Much Damn Money

We have seen experimental evidence that survey respondents express a strong preference for transparency – and additional survey evidence that respondents in states with open meetings laws actually seem to know less about legislatures themselves.Justin H. Kirkland, Jeffrey J. Harden 2022

The Illusion of Accountability: Transparency and Representation in American Legislatures

But mandated disclosure is like Kennedy after the Bay of Pigs: “The worse I do, the more popular I get.” Or like Dr. Johnson’s description of second marriages: “the triumph of hope over experience.” For disclosure does not work, cannot be fixed, and can do more harm than good. It has failed time after time, in place after place in area after area, in method after method, in decade after decade. Mandated disclosure’s failure is no stranger than its popularity. Disclosures are the fine print everybody derides, the interminable terms everybody clicks agreement to without reading. Disclosures describe complex facts in complex language; most people little like the former and little understand the latter. Decisions requiring sophistication and expertise cannot be bettered by pelting the unsophisticated and inexpert with data.Omri Ben-Shahar & Carl E. Schneider 2014

More Than You Wanted to Know: Failure of Mandated Disclosure

E. B. White has defined democracy as a “recurring suspicion that more than half of the people are right more than half of the time” This is necessary to our self-image. But there is a difference between recurring suspicion and constant conviction. Issues in these times have become so complicated that many of them are fully understood only by experts and by officials and legislators with staffs of experts at their disposal. The rest of us are sometimes forced to accept their decisions on faith or to oppose them on a hunch that they are wrong.Kenneth G. Crawford 1971

Is “Liberal Reform” All to the Good?

The silent majority is not going to be present at the open markups of the bills; they are going to be too busy and too occupied otherwise. But if you have open markup on bills...do you not think that the special interests will be there? The silent majority will not be there, but the special interests will be well represented.Rep George Mahon 1970

Congress & the People

For the most recent edition of “Lie Witness News,” Kimmel sent his team out to Hollywood Boulevard to ask people if they had voted in the midterms. Several of the participants were quick to decree that they had already gone to the polls that morning. But there was one major problem: It wasn’t election day.Megan McCluskey 2018

Lie Witness News

In the United States, most Americans oppose “welfare” but support “aid to the poor.” They want to decrease spending on foreign aid and increase spending on foreign aid. They want to amend the Constitution but oppose changing it. They oppose regulations that harm businesses but they also support regulations that protect the public. Contradictory findings like these have puzzled students of public opinion for decades. On too many issues there doesn’t seem to be any there “there.” The public just doesn’t make any logical sense. This leads many to conclude that the public simply has no idea what it is talking about. Richard Longoria 2018

Janus Democracy

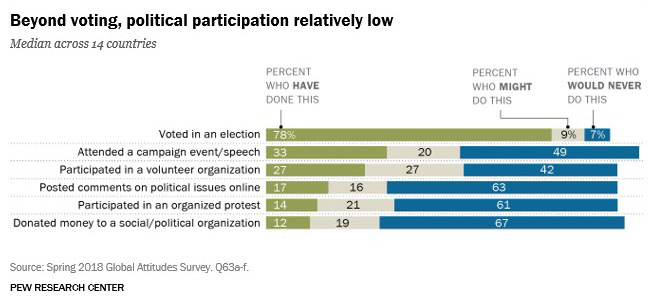

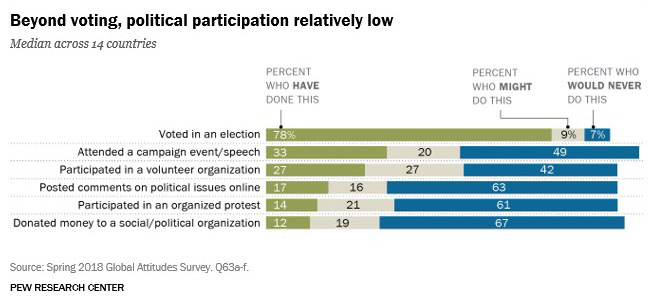

Pew Research Center 2018

Pew Research Center 2018

As noted, most voters are not informed, especially about projects that don’t affect them very much.Deborah Walker 2020

Public Choice - Logrolling

This is the dirty little secret of our profession. Among political scientists, that most voters are woefully ignorant about politics is completely uncontroversial, and has been for decades. The survey evidence on this subject is overwhelming. Yet it is not something widely disseminated, and a good deal of effort in the discipline is devoted to scrounging for reasons why the severe knowledge deficits of voters don’t matter all that much, and why Washington will be attentive to voters’ demands even if most voters are not very well informed and not paying all that much attention. Jacob Hacker & Paul Pierson 2010

Winner-Take-All Politics

In transparency models and narratives, the ‘public’, rather than representing an adjective to describe a certain social and political sphere, is instead understood as a noun to denote a group of people. This group of people is assumed to see its relationship to the state as a contract that it is willing to enforce by using democratic leverage to hold government to account and uphold the principals of good governance. It is unlikely, however, that such a public can be found in any pure form outside the abstract models of political scientists and the discourse of policymakers (Fenster 2015; Fox 2015). It is therefore problematic for policymakers to assign to citizens beliefs, interests and incentives, and a specific relationship to the state based on some kind of moral responsibility or ‘public duty’ to mobilize and participate in what essentially needs to be a collective action for change. Paivi Lujala and Levon Epremian 2017

Transparency and natural resource revenue management: empowering the public with information?

Despite the late hour, the marble-lined committee room is packed to the doors with ‘people,’ and guards are stationed at the entrance to stop more from pushing in. Reporters sit cheek-by-jowl around two tables not far from the door, and the remainder of the room is filled with lobbyists – lots of lobbyists. [No constituents are present]Jeffery Birnbaum & Alan Murray 1988

Showdown at Gucci Gulch (1986 Tax Reforms)

Trial judges hand out more prison and jail time to defendants just before they come up for reelection...In spite of the tremendous power wielded by trial court judges the study showed that “voters are almost entirely uninformed about judge behavior.” [But] because voters tend only to evaluate a judge’s performance just prior to election most judges ignore constituent preferences while in office then try to portray a “tough on crime” stance just prior to the election.Gary Hunter 2009

Elected Judges More Punitive Just Before Elections

Sometimes the “opinions” reported in polls do not exist. Because respondents do not like to say “I don’t know,” they often pick an answer more or less at random. When George Bishop of the University of Cincinnati asked in surveys about the “Public Affairs Act of 1975,” the public offered opinions even though the act was fictional. (And when The Washington Post celebrated the fictional act’s 20th anniversary by proposing its repeal, the public offered opinions about that as well.) Of course, on some issues the public has well-formed opinions, but on many others their opinions may represent nothing more than spontaneous impressions.James S. Fishkin 2006

The Nation in a Room - Turning Public Opinion into Policy

Representatives should do what their constituents would support if their constituents were well informed about the issue. Even Edmund Burke invoked this notion when he claimed, in his classic “Speech to the Electors of Bristol” defending the independent judgment of representatives, that if his constituents only knew what he knew—some 300 miles away in London—then they would agree with him. Hence there seem to be three main roles for the legislator: to represent the wishes of the constituents, to do what one thinks is best, and to represent the hypothetical informed views of constituents. As a retired and influential Congressional lobbyist told me, “Most members would like to do the right thing, if only they can get away with it.”James S. Fishkin 2006

The Nation in a Room - Turning Public Opinion into Policy

Winston Churchill did not say this

Winston Churchill did not say this

Between the lobbyists, who arrived early and stayed all day seeking scarce committee room seats, and platoons of staff and press, Senate committee sessions were well attended – but not by the general public. Except for those whose livelihoods depended on it, there wasn’t much interest in the tax code arcania.Martha Hamilton 1984 – The Washington Post

Opening Up Congress

In theory, every citizen makes up his mind on public questions and matters of private conduct. In practice, if all men had to study for themselves the abstruse economic, political, and ethical data involved in every question, they would find it impossible to come to a conclusion about anything. Edward Bernays 1928

Propaganda*NOTE: Bernays insisted that the public could be controlled because they are not just unwilling to follow the inner-workings of government, but they are also unable to do so. He was hired by business to fight back against the New Deal and manipulate the masses into believing that business not government was the reason why America was so successful.

There's a good reason why nobody studies history, it just teaches you too much.Noam Chomsky 2020

Nobody Studies History

We survey a substantial body of scholarly work demonstrating that most democratic citizens are uninterested in politics, poorly informed, and unwilling or unable to convey coherent policy preferences through “issue voting.” How, then, are elections supposed to ensure ideological responsiveness to the popular will? In our view, they do not. The populist ideal of electoral democracy, for all its elegance and attractiveness, is largely irrelevant in practice, leaving elected officials mostly free to pursue their own notions of the public good or to respond to party and interest group pressures.Christopher Achen & Larry Bartels 2016

Democracy for Realists

To illustrate how few people actually read its terms and conditions disclosure, the online retailer Gamestation, on April Fools’ Day 2010, replaced the usual text with what it called an “immortal soul clause,” which read: “By placing an order via this Web site on the first day of the fourth month of the year 2010 anno Domini, you agree to grant us a non-transferable option to claim, for now and forever more, your immortal soul.” Eager to get on with their online purchase, 88 percent of customers clicked the box to sell their souls. (The 12 percent who opted out were rewarded with a cash credit for their diligence.) But information overload, not consumer laziness, is often to blame, Professor Sovern says. At real estate closings, in less than an hour, buyers sign reams of paper they are seeing for the first time — including the mortgage disclosure form — to take ownership of a residence they’ve already chosen. Everyone signs, Professor Sovern says, adding: “Predatory lenders try to distract people with lots of paper. I think disclosures sometimes create the illusion of consumer protection — enabling legislators to claim credit for consumer protection, without the reality.”Elisabeth Rosenthal 2012

I Disclose... Nothing / Hard Truths about Disclosure

Democratic opportunities can be hijacked for individual gain and special interests. The naive assumption that citizens will live up to highly idealized expectations of citizen responsibility can lead to democratic capture and distortion. DemocraciesBruce Cain 2014

The Transparency Paradox

Democracy for Realists assails the romantic folk-theory at the heart of contemporary thinking about democratic politics and government, and offers a provocative alternative view grounded in the actual human nature of democratic citizens. Christopher Achen and Larry Bartels deploy a wealth of social-scientific evidence, including ingenious original analyses of topics ranging from abortion politics and budget deficits to the Great Depression and shark attacks, to show that the familiar ideal of thoughtful citizens steering the ship of state from the voting booth is fundamentally misguided. They demonstrate that voters―even those who are well informed and politically engaged―mostly choose parties and candidates on the basis of social identities and partisan loyalties, not political issues. They also show that voters adjust their policy views and even their perceptions of basic matters of fact to match those loyalties. When parties are roughly evenly matched, elections often turn on irrelevant or misleading considerations such as economic spurts or downturns beyond the incumbents' control; the outcomes are essentially random. Thus, voters do not control the course of public policy, even indirectly.Christopher Achen & Larry Bartels 2016

Democracy for Realists

We require so many of our institutions to be chosen through elections, for example, on the view that “citizen” control will keep officials hewing closer to the common good, without any realistic assessment of how the electoral process actually works; with romanticized views of how much interest most citizens will take (or rather, fail to take) in voting for lower-level offices; and without regard for the degree to which organized private interests will be able to dominate in low turnout, low salience elections.Richard H. Pildes 2013

Romantacizing Democracy

In general, voters are ignorant, misinformed and biased. But there is tremendous variance. When it comes to political information, some people know a lot, most people know nothing and many people know less than nothing.Jason Brennan 2016

Against Democracy

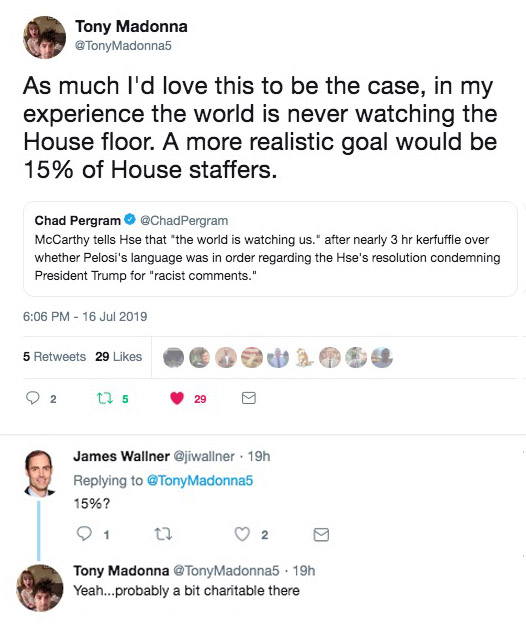

Anthony Madonna 2019 - The World is Never Watching

Anthony Madonna 2019 - The World is Never Watching

Citizens aren’t just ignorant or misinformed, but irrational. Few citizens process information with an open mind; most citizens disregard any information that contradicts their current ideology. Voters suffer from a wide range of biases, including confirmation bias, disconfirmation bias, motivated reasoning, intergroup bias, availability bias and prior attitude effects.Jason Brennan 2016

Against Democracy

“The people,” Roger Sherman told the Convention, “should have as little to do as may be about the government. They want information and are constantly liable to be misled.”Neil MacNeil 1963

Forge of Democracy

The broad public simply is not able to monitor congressional activity with nearly the consistency or intensity of organized interests.Frances Lee (Princeton) 2019

Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress

A 1973 citizenship examination administered by the National Assessment of Educational Progress showed that teenagers and young adults “know frighteningly little about the personalities or policies of governmental leaders, and have not even begun to understand the workings of the American political process.”Ronald Garay 1984

Congressional Television

John Hibbing 2002 - Survey of Americans on their participation in government

John Hibbing 2002 - Survey of Americans on their participation in government

As a rule, we can suppose. that most citizens know very little about politics and policies. Indeed, an informal survey suggests that most of my professional political science colleagues do not recall the congressional attack on the IRS, which was front-page news a few years ago.Russell Hardin 2007

The Economics of Transparency in Politics

Earnest and able democratic citizens will often lack the time to choose representatives wisely... Moreover, well-meaning but untutored, unsure, or merely busy, citizens can easily be led astray by political partisans; and in a democracy, they tend to be swayed by partisans who advocate the unlimited expansion of popular power. Democratic citizens will constantly be urged, and tempted, to press for increasing the power of the majority without being able to assure its wisdom or justice.Harvey Mansfield & Delba Winthrop 2000

Tocqueville: Democracy in America

The facts are significant. According to the last census, there are in America over fifty-four millions of men and women classed as citizens of twenty-one years of age and over. In the last election of November, 1920, despite the fact that we were keyed up by a great war, and despite the fact that the foreign policy of the nation at issue was of greater importance than any problem which had confronted the voter for a generation, and also despite the large expenditure of money by the two parties, only 26,000,479 voters went to the polls. In other words less than one half of those who could vote, voted. And consider what happens in a local election. On an average, not more than one tenth of our voters attend party primaries. In Boston less than one third of the registered voters cast their vote for city councilmen or school committeemen in a recent minor election.Samuel Spring 1922

The Voter Who Will Not Vote (Harper’s)

Nowhere and at no time in the history of the colonies did any newspaper or magazine report one single assembly debate. We have noticed a few fragmentary exceptions when speeches made in assemblies were cited in the course of political polemics. But these were individual speeches, not debates, and do not constitute an exception to the rule. Colonial editors were…certainly aware that such communication was possible…They could, however, have provided an outlet for members who wanted their speeches published, but this was not done either. In general, it appears that the demand did not exist. J.R. Pole 1983

The Gift of Government

Trevor Corning, Reema Dodin & Kyle Nevins 2017 - Inside Congres

Trevor Corning, Reema Dodin & Kyle Nevins 2017 - Inside Congres

Rep. Tauke said “An interest group with a specific issue will be very motivated to make its views known and learn what happened. The general public is not so motivated… But behind closed doors, lobbyists don’t know everything that is going on.”Richard Cohen 1994 p131

Washington at Work: Back Rooms and Clean Air*NOTE: This citation refers to the successful passage of the 1990 Clean Air Amendments (the most powerful environmental legislation in the past 40 years), which were brokered almost exclusively behind closed doors by Mitchell and others expressly to avoid the pressure of lobbyists. Full citation can be found here.

Even with the impressive growth of C-SPAN, which provides, via cable TV, admission to the House and Senate galleries for more than 54 million homes, the public’s awareness of Congress remains shallow.Richard Cohen 1994

Washington at Work: Back Rooms and Clean Air

Grave responsibilities are imposed upon the legislator by the fact that the public rarely has any useful opinion in matter of detail... Indeed, the ignorance of the public about [matters] is one of the causes of [secrecy’s] usefulness.Robert Luce 1926

Congress: An Explanation

When it comes to political information there are two groups of people. One group is almost completely ignorant of almost every detail of almost every law and policy under which they live. The other group is delusional about how much they know. There is no third group... every one of us is almost completely ignorant of almost every detail of almost every law and policy under which we live.Arthur Lupia 2014

Uninformed: Why People Know So Little About Politics

Senator Howell Heflin 1986 - A Sonnet on Transparency

Turn the spotlight over here.

Focus the camera at my place.

Pages, please don’t come near,

Otherwise, you just might block my face.

Some have made the worst claim yet,

That viewers will tire from the dull plot,

But I’ll be willing to make a bet

Lobbyists will watch a whole lot.

Senator Howell Heflin 1986 - A Sonnet on Transparency

Focus the camera at my place.

Pages, please don’t come near,

Otherwise, you just might block my face.

Some have made the worst claim yet,

That viewers will tire from the dull plot,

But I’ll be willing to make a bet

Lobbyists will watch a whole lot.

Even world-renowned experts on specific legal or political topics are almost completely ignorant of almost all of the details of the many laws, rules, and regulations under which any of us live.Arthur Lupia 2014

Uninformed: Why People Know So Little About Politics

Somewhat surprisingly, perhaps, the poll also showed that many Americans are still not paying close attention to tax reform. Only one out of ten reported that they were very familiar with the tax-reform packages before Congress, and 36% said they were not familiar at all.Evan Thomas 1986

Lights, Cameras, Tax Reform!

To some extent, the elites keep the people from implementing dumb policies, policies the people support only because they’re badly informed. Jason Brennan 2016

What History Teaches Us About Demagogues

In theory, democracy is a bulwark against socially harmful policies. In practice, however, democracies frequently adopt and maintain policies that are damaging. How can this paradox be explained? The influence of special interests and voter ignorance are two leading explanations...The central idea is that voters are worse than ignorant; they are, in a word, irrational – and they vote accordingly. Despite their lack of knowledge, voters are not humble agnostics; instead, they confidently embrace a long list of misconceptions.Bryan Caplan 2007

The Myth of the Rational Voter

More systematically, the most recent National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) tests found that fewer than a quarter of eighth- and twelfth-graders nationally could be considered “proficient or above” in civics, and the results were even worse for some sub-groups. This is not a result of recent churns in federal education law, by the way – these figures were just as bad, even a little worse, when the test was first given in 1998. In fact, the 1996 book What Americans Know About Politics and Why It Matters found the answer to the first part of its title had always been “not much”; fifty years of political science survey research had documented that “levels of information about public affairs are... astonishingly low.” A famous study of the 1948 election by Bernard Berelson, Paul Lazarsfeld, and William McPhee concluded that “voters today seem unable to satisfy the requirements for a democratic system of government.” Andrew Rudalevige 2017

Too many Americans know too little about the Constitution

Voters Worn Out - New York Times 2019

Voters Worn Out - New York Times 2019

The last thing people want is to be more involved in political decision making: They do not want to make political decisions themselves; they do not want to provide much input to those who are assigned to make these decisions; and they would rather not know all the details of the decision-making process. Most people have strong feelings on few if any of the issues the government needs to address and would much prefer to spend their time in nonpolitical pursuits.John Hibbing & Elizabeth Theiss-Morse 2004

Stealth Democracy

Transparency undermines expertise in a significant way, because it confines experts using the kinds of reasons that nonexperts can understand. But if you think about it for a second, you should realize that a lot of expert reasoning is by its nature, incomprehensible to the public.C. Thi Nguyen 2021

Transparency is Surveillance

Evidence of the people’s desire to avoid politics is widespread, but most observers still find it difficult to take this evidence at face value. People must really want to participate but are just turned off by some aspect of the political system, right? If we could only tinker with the problematic aspects of the system, then the people’s true participatory colors would shine for all to see, right? As a result of this mindset, when the people say they do not like politics and do not want to participate in politics, they are simply ignored. Elite observers claim to know what the people really want – and that is to be involved, richly and consistently, in the political arena. If people are not involved, these observers automatically deem the system in dire need of repair.John Hibbing & Elizabeth Theiss-Morse 2004

Stealth Democracy

The House not only has opened up internally to invite broader participation among its members but has also opened much of its operations to inspection by the press and the public. The problem remains for both members and the public to monitor committee action in the House because so much is going on at once. In 1975 a record 3,881 open meetings of House committees and subcommittees made the job of participant, reporter, or citizen most difficult.Lawrence Dodd & Bruce Oppenheimer 1977

Congress Reconsidered – 1st Ed

The creation of a multiplicity of committees makes it difficult for the public or the press to follow policy deliberations even if they are open.Lawrence Dodd 1977

Congress Reconsidered – 1st Ed

Nothing in the empirical record suggests that citizens are at all well informed regarding the people, politics, and procedures of Congress.Jeffery Mondak 2007

Does Familiarity Breed Contempt?

Voters are woefully uninformed about the voting behavior of their elected members. This position is put succinctly by Miller and Stokes (1963, 47): “Far from looking over the shoulder of their Congressmen at the legislative game, most Americans are almost totally uninformed about legislative issues in Washington.” Reporting results from a survey of 100 members of Congress, Matthews and Stimson (1975, 28) report that “79 percent said their constituents seldom knew or cared how they voted.” More recently, Dancey and Sheagley (2013) find most voters cannot correctly identify how senators voted on important roll call votes when they adapt positions contrary to their party. Similarly, using a survey of 30,000 respondents, Highton (2018) reports little evidence linking roll call votes, voter preferences and member vote share. As voters lack the ability to monitor, instead of providing an opportunity to express sincere positions members view roll call votes as an opportunity to “position-take” for other elites (Mayhew 1974).

Outside groups consisting of think tanks, interest groups and campaign donors are far more reliable in terms of monitoring member actions. In the contemporary U.S. Congress, there are over a hundred different interest groups that track member votes (Davidson, Oleszek, Lee and Schickler 2013). The result is that member roll call votes are prominently featured in a large number of attack ads. A common tactic is to feature how often a member voted with an unpopular national figure, like a President or the Speaker of the House (Carson, Crespin and Madonna 2014). For example, in 2014, Republicans put out an advertisement asserting that Rep. John Barrow (D-GA) voted with President Barrack Obama 85 percent of the time (Jacobson 2014). And although he supported Republican John McCain’s presidential campaign in 2008, Rep. Gene Taylor (D-MS), was still attacked in campaign ads for voting with former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi 82 percent of the time (Taylor 2010).Michael Lynch, Anthony Madonna & Kisaalita 2018

Broken Record - Transparency, Position Taking and Recorded Voting in the US Congress (THE LINKED PAPER (2017) IS DIFFERENT FROM THE UPDATED VERSION (2018))

Consitituents generally do not and cannot follow the development of information and arguments on an issue.Larry Milbrath 1963

The Washington Lobbyists

Instead, I examined the role of voters’ ignorance of their representatives’ corruption. American voters are (in)famously uninformed about politics. What I found is that voters’ inattentiveness to politics is strongly associated with lower propensity to vote against a corrupt incumbent.Marko Klašnja 2017

Voters’ Ignorance

There is then nothing particularly new in the disenchantment which the private citizen expresses by not voting at all, by voting only for the head of the ticket, by staying away from the primaries, by not reading speeches and documents, by the whole list of sins of omission for which he is denounced. I shall not denounce him further. My sympathies are with him, for I believe that he has been saddled with an impossible task and that he is asked to practice an unattainable ideal. I find it so myself for, although public business is my main interest and I give most of my time to watching it, I cannot find time to do what is expected of me in the theory of democracy; that is, to know what is going on and to have an opinion worth expressing on every question which confronts a self-governing community. And I have not happened to meet anybody, from a President of the United States to a professor of political science, who came anywhere near to embodying the accepted ideal of the sovereign and omni-competent citizen.Walter Lippman 1925

The Phantom Public

For the real environment is altogether too big, too complex, and too fleeting for direct acquaintance. We are not equipped to deal with so much subtlety, so much variety, so many permutations and combinations. And although we have to act in that environment, we have to reconstruct it on a simpler model before we can manage it.Walter Lippman 1922

Public Opinion

So I have been reading some of the new standard textbooks used to teach citizenship in schools and colleges. After reading them I do not see how anyone can escape the conclusion that man must have the appetite of an encyclopedist and infinite time ahead of him. To be sure he no longer is expected to remember the exact salary of the county clerk and the length of the coroner’s term. In the new civics he studies the problems of government, and not the structural detail. He is told, in one textbook of five hundred concise, contentious pages, which I have been reading, about city problems, state problems, national problems, international problems, trust problems, labor problems, transportation problems, banking problems, rural problems, agricultural problems, and so on ad infinitum. In the eleven pages devoted to problems of the city there are described twelve sub-problems.Walter Lippman 1925

The Phantom Public

Legislators in Bolivia and Colombia – even those who strongly favored recorded voting themselves – described a general lack of public attention to individual legislators’ voting behavior. Nevertheless, there are pockets of interest. Organized interest groups – unions, business organizations, and farmers’ groups – sometimes monitor legislative voting, even in systems where no records are kept, and lobby legislators and party leaders to support their demands.John M. Carey 2009

Legislative Voting and Accountability

The usual appeal to education can bring only disappointment. For the problems of the modem world appear and change faster than any set of teachers can grasp them, much faster than they can convey their substance to a population of children. If the schools attempt to teach children how to solve the problems of the day, they are bound always to be in arrears.Walter Lippman 1925

The Phantom Public

When Congress is engaged in meaningful debate, when it is being newsworthy by passing important legislation and by checking presidential power, people are least happy with the institution. One writer correctly observes “the less people hear from Congress, the higher Congress’ ratings soar.”John Hibbing and James Smith 2001

What the American Public Wants Congress to Be

Full Article

The United States House of Representatives is among the most transparent and representative legislative bodies in the world. All citizens have the right to call or visit their representative’s offices and offer their opinions. Television cameras record and TV stations (and now the Internet) disseminate a variety of speeches, votes, debates, committee meetings, and other legislative actions of lawmakers. Records of representatives’ opinions, statements, votes, and finances are publicly available and searchable. The floor of the House of Representatives is a manifestation of majority ruled politics. Yet even with these transparent building blocks, the House of Representatives, like many other systems, has procedures so complex and evolving that few individuals are able to fully grasp the entirety of what goes on and to imagine how to impact the process. Trevor Corning, Reema Dodin & Kyle Nevins 2017

Inside Congress

Public opinion research shows that voters are poorly informed about their representative’s votes on even the most highly visible legislation (Ansolabehere and Jones 2010; Jones 2011; Sulkin 2009),Michael Lynch & Anthony Madonna 2017

Broken Record

Jenkin Lloyd Jones 1957 on the failure of Greek transparency

Jenkin Lloyd Jones 1957 on the failure of Greek transparency

Most Americans have neither the time, the interest, nor the inclination to monitor Congress on a day-to-day basis. But lobbyists and activists do, and they can use the information and access to ensure that the groups they represent are well taken care of in the federal budget and the legal code. This is true not only for lobbies that want money. On any number of issues, from tort law to American policy toward Cuba to quotas, well organized interest groups – no matter how small their constituencies can ensure that government bends to their will. Reforms designed to produce majority rule have produced minority rule.Fareed Zakaria 2003

Future of Freedom

The unthinking multitude...domestic cattle...Laziness and cowardice are the reasons why such a large part of mankind gladly remain minors all their lives.Immanuel Kant 1784

What Is Enlightenment?

Contrary to Robespierre’s vision, many in Paris in 1791 were going about their everyday lives with little regard to the Revolution. The number of marriages and baptisms had risen significantly since the previous year and the mortality rate was falling. Judging by the small ads posted in the daily Chronique de Paris, the people still had plenty of mundane concerns. One Mme Gentil of the rue de Richelieu offered a handsome reward for her lost greyhound. There were elegant apartments to rent with facilities for stabling horses or parking carriages, as well as plenty of more modest accommodations. Opticians, hairdressers, pharmacists, dentists specializing in teeth whitening, and chiropodists all promoted their skills. An Italian singer just arrived in the city offered home tuition. Exchange visits between French and English children were still being advertised. Oysters, oranges, and other luxury comestibles continued to be imported. In the theaters and opera houses, the Revolution was being culturally assimilated. Jean-Baptiste Pujoulx wrote a play about the death of Mirabeau (La mort de Mirabeau) and Luigi Cherubini's instrumental music for it was performed in the Theatre Feydeau for the first time in May.Ruth Scurr 2006

Fatal Purity - Robespierre and the French Revolution

The mass public contains...a great many more people who know next to nothing about politics...The average American’s ability to place the Democratic and Republican parties and ‘liberals’ and ‘conservatives’ correctly on issue dimensions and the two parties on a liberal-conservative dimension scarcely exceeds and indeed sometimes falls short of what could be achieved by blind guessing. The verdict is stunningly, depressingly clear: most people know very little about politics.Robert Luskin 2002 Thinking About Political Psychology

How can citizens control legislators when most citizens pay scant attention to public affairs? Why should legislators worry about citizens’ preferences when they know most citizens are not really watching them?Douglas Arnold 1993

Can Inattentive Citizens Control Representatives?

Efforts to publicize government performance can become “data dumps” such that the average legislator or citizen finds it nearly impossible to find specific, useful information. There has been an explosion of data in government. While there is certainly nothing inherently wrong with providing more performance data, often the form in which the data is provided makes it very difficult to locate specific information. In too many cases, websites focused on government performance are simply a collection of long government performance reports. It requires someone with a thorough knowledge of the organization of the jurisdiction (which agency is responsible?) and the policy area in question (what‘s a good performance measure?) to find and interpret these data.Philip Joyce 2015

The Dark Side of Government in the Sunshine

The 1990 Clean Air Act was about 800 pages long, and nonexperts would need a translator to make sense of it.Barbara Sinclair 2006

Unorthodox Lawmaking

Politicians know the American people, millions of them, don’t know very much and they count on that, and that's why they use bumper stickers and slogans and they appeal to fear...You can’t have a rational discussion with the American people because it goes over their head...only 2 out of 5 voters can name the three branches of the federal government.Rick Shenkman 2016

The Open Mind

It is necessary to say that people are deluded and that the task of leadership is to un-delude them.James Traub 2016

It’s Time for the Elites to Rise Up Against the Ignorant Masses

Further evidence of the emergence of a somewhat different institutional climate in which concerns with restoring decisionmaking capabilities had begun to compete with demands for openness, participation, and decentralization came in 1983, when the return by the Ways and Means Committee to the traditional practice of closing bill-writing sessions to the public excited little interest or criticism.Randall Strahan 1989

The New Ways and Means

The problem is, of course, is that if Americans aren’t paying attention, they can’t hold anybody accountable...If we use statistics on what the people don’t know...the statistics are just appalling.Rick Shenkman 2008

CNN (How Stupid Are Americans)

During election years, most citizens cannot identify any congressional candidates in their district. Citizens generally don’t know which party controls Congress. During the 2000 U.S. presidential election, while slightly more than half of all Americans knew Gore was more liberal than Bush, significantly less than half knew that Gore was more supportive of abortion rights, more supportive of welfare-state programs, favored a higher degree of aid to blacks or was more supportive of environmental regulation. When asked to guess what the unemployment rate was, the majority of voters tend to guess it is twice as high as the actual rate.Jason Brennan 2016

Against Democracy

Less than 30% of Americans can name two or more of the rights listed in the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights.Jason Brennan 2016

Against Democracy

Things are worse than [survey] numbers indicate. Simple surveys of voter knowledge — such as Pew Research Center polls or the American National Election Studies (ANES) – tend to overstate how much Americans know. One reason these surveys overstate voter knowledge is that they usually take the form of a multiple-choice test. When many citizens do not know the answer to a question, they guess. Some of them get lucky, and the surveys mark them as knowledgeable. Imagine I administer a twelve-question test to ten thousand voters, and each question has three choices for an answer. Now suppose the average American gets four out of twelve questions correct. It might be that the average American knows the answer to four questions, but this is indistinguishable from them guessing at random.Jason Brennan 2016

Against Democracy

But are the people really populists and would enactment of the populist reform agenda really make Congress more popular? Recently collected data suggest the answer to both questions is no. These data consist of a specially designed national survey and numerous focus groups held across the country. In their survey responses and in their focus group comments, the people left the clear impression that the last thing they want is more involvement in the political process. Accountability and the representation of varied views were far from their minds. They did not have a particularly charitable view of their fellow citizens, and they certainly did not perceive them as well-situated to make informed and enlightened public policy decisions. They betrayed no motivation to study the issues more, to spend more time listening to candidate debates, to discuss the issues themselves, or to be more intimately involved in any way with the political process.John Hibbing 2002

How to Make Congress Popular

The evidence is clear, most Americans know very little about politics and many don’t have any interest in politics at all. Most Americans can’t identify which party is in control of Congress. This makes it difficult for voters to assign credit or blame for their performance. They are notoriously bad at estimating how much is spent on various programs, and they overestimate the cost of some programs, like the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, while underestimating the cost of others, like Social Security. They are ignorant about the basic structure of government and can’t identify many of the rights citizens have or the limits that the Constitution imposes on the government. They don’t know what is in specific pieces of legislation, like the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act of 2009, and attribute legislation to the wrong elected official-many believe the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) was enacted during the Obama administration. A majority of Americans incorrectly believed that President Bush claimed there was a “link between Saddam Hussein and the September 11 attacks.” Voters can’t hold their elected officials responsible if they can’t identify their elected officials, don’t know what is in legislation, and don’t know which elected officials supported which government programs. Richard Longoria 2018

Janus Democracy

[The people] know nothing about government or current events. They can't follow arguments of any complexity. They stuff themselves with slogans and advertisements. They eschew fact for myth. They operate from biases and stereotypes, and they privilege feeling over thinking. The result is a political system of daunting irrationality.Louis Bayard 2008

Too Dumb to Vote

Voters consistently misperceived where candidates stood on important issues.Larry Bartels 2008

How Smart is the American Voter?

The complexity and incoherence of our government often make it difficult for us to understand just what that government is doing... one need look no further than the mind-numbing complexity of the health-care system, or our byzantine system of funding higher education, or our bewildering federal-state system of governing everything from welfare to education to environmental regulation. America has chosen to govern itself through more indirect and incoherent policy mechanisms than can be found in any comparable country.Steven M. Teles 2013

Kludgeocracy in America

Madison’s principal reason for deifying the Founders was his belief that the people could not be trusted to intelligently rule themselves.Michael J. Klarman 2016

The Framers’ Coup

Transparency, unlike other forms of regulation, has a major disadvantage: it assumes that those who receive the information released by producers or public officials can properly process it and that their conclusions will lead them to reasonable action. However, the well-known and often-cited findings of behavioral economics demonstrate that very often the public is unable to properly process even rather simple information because of “wired in,” congenital, systematic cognitive biases.Amitai Etzioni 2010

Is Transparency the Best Disinfectant?

One of the folk arguments for electing government officials is “accountability.” Citizens, the story goes, need to be able to hold elected officials accountable, and one way to hold them accountable is to retain the right to fire and replace them. But in the case of city treasurers, it’s easy to measure (much of) the job the treasurer is doing: just look at the interest rate on the city debt. But even when such a key quality index is so easy to measure, voting citizens do an awful job of keeping the city treasurer accountable. The better option is to let other city officials – the elected mayor, the city council, or maybe the appointed city manager – pick a treasurer and then keep an eye on the job she’s doing. Those city officials will surely notice if the treasurer is saving the city over $200,000 a year, even if voters are too preoccupied watching cat videos to do the job.Garrett Jones 2020

10% Less Democracy

Polling data have consistently shown that most of the public view the institution of Congress with contempt but are more tolerant of their own local members. Some of the hostility derives from citizens’ lack of comprehension of how Congress operates; also, they have little opportunity to track the progress of important measures through Congress. The progress toward the 1990 Clean Air Act, for example, produced a mere handful of stories on the three television networks’ evening news programs in 1989-90. Coverage in The New York Times and The Washington Post, the major newspapers for the nation’s intelligentsia, was sporadic, dealing with small parts of the story without filling in the larger picture. Even with the impressive growth of C-SPAN, which provides, via cable TV, admission to the House and Senate galleries for more than 54 million homes, the public’s awareness of Congress remains shallow. Richard Cohen 1994

Washington At Work

The right of free men to rule themselves by the ballot seems celestial in its sanction. All Americans boast of enjoying it. Orators passionately play the gamut of human emotions in praise of it until they reach the final note of ennui. On the Fourth of July we celebrate it proudly as our heritage and our portion in life. Indeed, most of us would die to maintain the right to representation in government. And yet on the rainy election morning, when “the fate of the nation hangs in the balance,” from a fourth to a half of us invariably do not vote. We either oversleep, and thus are too rushed to catch our train, or procrastinate until the afternoon and then completely forget about voting. Some of us even fail to remember that there was any election at all! Samuel Spring 1922

The Voter Who Will Not Vote (Harper’s)

few politicians believe that citizens do their democratic duty and vote for a party because of its policy profile. In politicians’ conception, voters hardly take into account the party’s policy promises for the future nor the party’s past behavior when casting their vote. Instead, most MPs believe that citizens are seduced to vote for a party because of individual candidates on the party list, and because of the party’s campaign communications.Karolin Soontjens 2023

Voters don’t care too much about policy

Those who compare the eagerness of the voter to read the stock ticker or attend sporting events with his failure to vote, overlook human nature. We are living in a distracting, harrowing age, where a great strain is imposed upon us all. Monotony and nervous exhaustion are the twin demons of modern-city civilization. We cry out for relaxation, for relief, for excitement before all else. Watching the stock ticker affords us the gambler’s joy and relief. Watching the baseball scores and parades is a form of amusement that appeals to those of us who live under the blight of our modern cities. But voting is a duty. Like going to school, it is the right thing to do, but it is neither interesting, exciting, nor enjoyable. The voter to-day has problems and troubles enough in order to fight off the undying wolf from his doorstep, and cannot be expected to vote unless he is summoned to the polls in some unmistakable, vigorous manner. We must sadly remind him that he has one more duty added to his burden. He must vote as well as pay taxes. Voting cannot be continued as a side issue or an act of patriotism.Samuel Spring 1922

The Voter Who Will Not Vote (Harper’s)

I investigate low levels of political awareness among Americans. I focus on whether people understand issues incorrectly or are simply disengaged and inattentive. There is an important difference between them. Those who are uninformed simply do not know, which would make it easier to turn them into informed citizens. All that would be needed is for them to access the right information. For those who are misinformed, however, it is a tougher task. They believe that their answer is right, and even though they are in fact wrong, they are more willing to fight the truth in order to validate what they feel is the right answer. I analyze this phenomenon with Public Mind Polling data from Fairleigh Dickinson University. I anticipate my results to show that less use of news media will decrease a person’s level of knowledge and increase their degree of disengagement, while loyalty to a limited number of media sources is likely to increase a person’s level of misinformation.Kyle Priest 2017

Churchill’s Argument Against Democracy: The Average Voter. Information Levels and News Sources among Americans

Evidence assembled by behavioral economists strongly indicates that people are neither as able to process information nor as likely to act on it as transparency theory presumes.Amitai Etzioni 2010

Is Transparency the Best Disinfectant?

Jack Abramoff on Deceiving Public 2015

Jack Abramoff on Deceiving Public 2015

Nothing strikes the student of public opinion and democracy more forcefully than the paucity of information most people possess about politics. Decades of behavioral research have shown that most people know little about their elected officeholders, less about their opponents, and virtually nothing about the public issues that occupy officials from Washington to city hall.John Ferejohn 1990

Information and the Electoral Process

Even if we assume that political circumstances do actually allow for a politically unconstrained and informed discussion of complex issues, as Arias-Maldonado (2007, p. 248) points out, ‘the belief that citizens in a deliberative context will spontaneously acquire ecological enlightenment, and will push for greener decisions, relies too much on an optimistic, naive view of human nature, so frequently found in utopian political movements’.Mark Beeson 2010

The Coming of Environmental Authoritarianism (Climate)

Most Americans today have only the most general sense of the constitutional role that Congress performs and few citizens have any clear conception of how Congress carries out its legislative responsibilities.Ronald Garay 1984

Congressional Television

[Voter’s] opinions flip depending on how a question is worded: they say that the government spends too much on “welfare” but too little on “assistance to the poor,” and that it should “use military force” but not “go to war.” When they do formulate a preference, they commonly vote for a candidate with the opposite one. But it hardly matters, because once in office politicians vote the positions of their party regardless of the opinions of their constituents. Steven Pinker 2018

Enlightenment Now

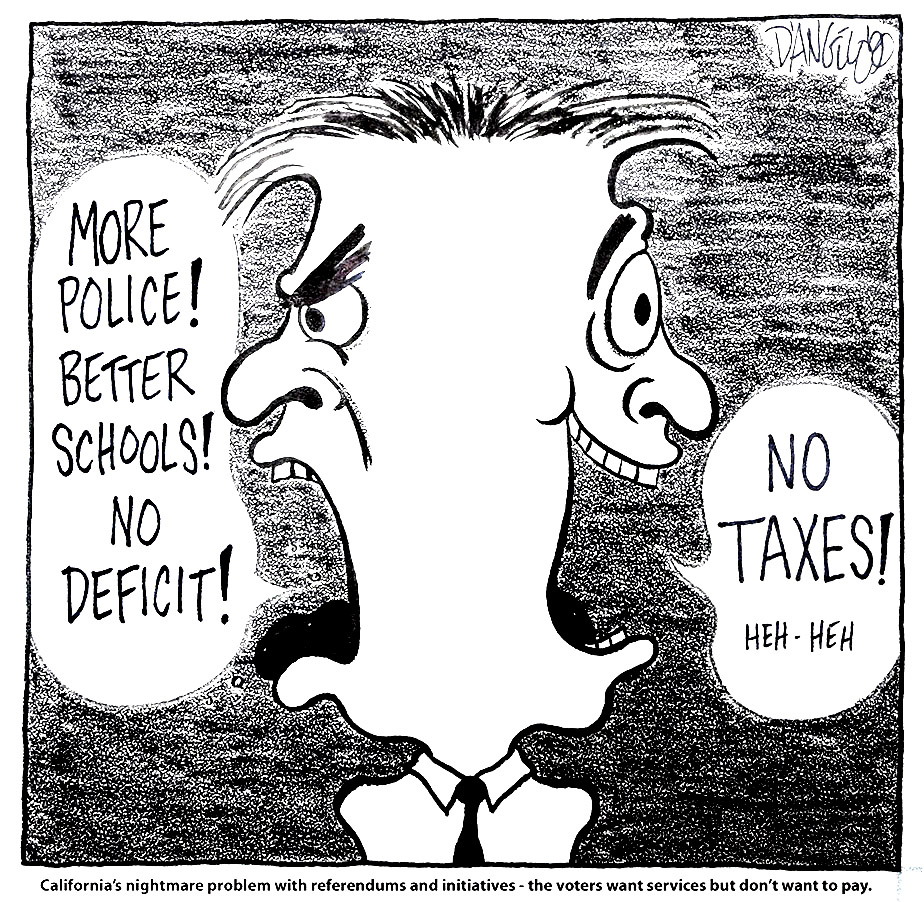

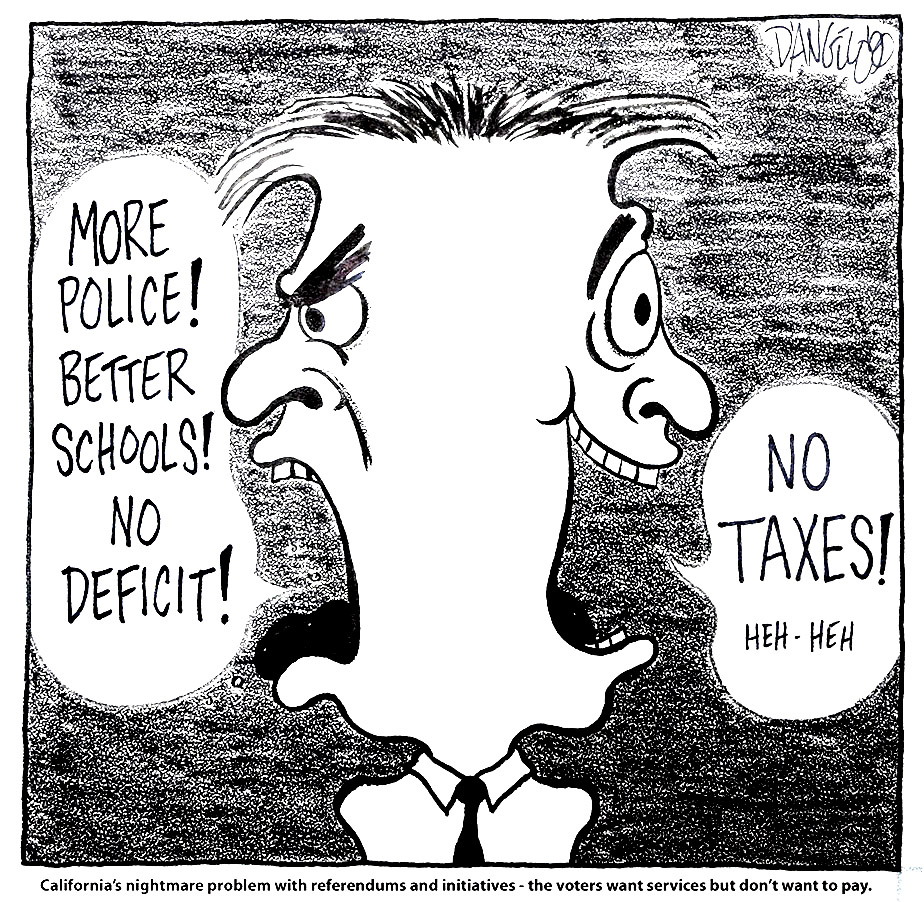

That government by initiative is so dysfunctional is no surprise. As the Public Policy Institute for California noted in its October 2012 report “Improving California’s Democracy,” less than 10 percent of all voters polled—Democrats, Republican, and Independents—said that they want the governor and legislature to make the tough choices involved in the state budget, while a full 80 percent said California’s voters should make those decisions through the initiative process. Yet only one in five voters said they know a lot about how state and local governments spend and raise money, and most “cannot name the largest area of state spending (K–14 education) or the largest area of state revenues (personal income taxes).” 64 Direct democracy in California had gone so awry that in 2011 The Economist published a cover story on the initiative process titled “Where It All Went Wrong: A Special Report on California’s Dysfunctional Democracy.”Nathan Gardels & Nicolas Berggruen 2019

Renovating Democracy

Gus D’Angelo 2011 - Nightmare of Initiatives

Gus D’Angelo 2011 - Nightmare of Initiatives

The second major theoretical claim of Downs is that individual citizens have no incentive even to learn enough to be able to vote their own interests intelligently...this citizen also builds opinions on cavalier ‘facts.’Russell Hardin 2009

How Do You Know?

The questions which really engage the emotions of the masses of the people are of a quite different order. They manifest themselves in the controversies over prohibition, the Ku Klux Klan, Romanism, fundamentalism, immigration. These, rather than the tariff, taxation, credit, and corporate control, are the issues which divide the American people. These are the issues they care about. They are just beneath the surface of political discussion. In theory they are not supposed to be issues. The party platforms and the official pronouncements deal with them obliquely, if at all. But they are the issues men talk about privately, and they are the issues about which people have deep personal feelings. Walter Lippman 1927

The Causes of Political Indifference

Even if voters were smothered with “costless” information, it is doubtful that they would pay attention and process detailed information about the complexities of public policy they do not care much about. In contrast, special interests are “naturally” better informed; compared to the general public, they get costless information as a by-product of their specialized activities, and they have stronger incentives to invest in costly information gathering, to pay costly attention to complex information, and to invest in costly expertise that allows them to understand such information. Susanne Lohmann 1998

Information Rationale For the Power of Special Interests

The truth is that most citizens pay very little attention to politics, and it shows. To call their knowledge of even the most elementary facts about the political system shaky would be generous. To take just a few examples, less than a third of Americans know that a member of the House serves for two years or that a senator serves for six. In 2000, six years after Newt Gingrich became House Speaker, only 55 percent knew the Republicans were the majority party in the House a success rate only a little superior to a random guess. Just two years after he presided over Bill Clinton’s impeachment trial in the Senate, only 11 percent of those surveyed could identify William Rehnquist as chief justice of the United States.

About policy, most voters know even less, and are prone to staggering mistakes. Roughly half of Americans think that foreign aid is one of the two top expenditures in the federal budget (in reality, it consumes about 1 percent of the budget). In 1980, in the midst of the Cold War, 38 percent of Americans surveyed believed that the Soviet Union was a member of NATO the anti-Soviet defense alliance. Two years after the huge 2001 tax cuts, half of Americans were unable to recall that there had been tax cuts at all. Most of the famous “swing voters,” whom journalists tend to idealize as standing above the fray, carefully sorting among the strengths and weaknesses of each party’s offerings, are actually the least engaged, least well-informed citizens, reaching a final decision (if at all) on the flimsiest grounds.Jacob Hacker & Paul Pierson 2010

Winner-Take-All Politics

Jason Brennan 2016 - Foreign Policy

Jason Brennan 2016 - Foreign Policy

The reality that most voters are often ignorant of even very basic political information is one of the better-established findings of social science. Decades of accumulated evidence reinforces this conclusion...The evidence shows that political ignorance is extensive and poses a very serious challenge to democratic theory...When President Barack Obama took office in 2009, his administration and the Democratic Congress pursued an ambitious agenda on health care and environmental policy, among other issues. The media covered both issue areas extensively. Yet a September 2009 survey showed that only 37 percent of Americans believed they understood the administration’s health care plan, a figure that likely overestimated the true level of knowledge. A May 2009 poll showed that only 24 percent of Americans realized that the important “cap and trade” initiative then recently passed by the House of Representatives as an effort to combat global warming addressed “environmental issues.” Some 46 percent thought that it was either a “health care reform” or a “regulatory reform for Wall Street.” It is difficult to evaluate a major policy proposal if one does not know what issue it addresses. In 2003, some 70 percent of Americans were unaware of the recent enactment of President George W. Bush’s Medicare prescription drug bill, the biggest new government program in several decades.Ilya Somin 2016

Democracy and Political Ignorance

America’s embarrassing little secret...is that vast numbers of Americans are ignorant, not merely of the specialized details of government which ordinary citizens cannot be expected to master, but of the most elementary political facts – information so basic as to challenge the central tenet of democratic government itself. Paul Blumberg 1990

What Americans Know about Politics

By the mid-1820s, according to historian Ronald P. Formisano, “the vast majority of citizens had lost interest in politics. They had never voted much in presidential elections anyway, and now they involved themselves only sporadically in state and local affairs.”Glenn Altschuler 2001

Rude America - 19th Century Participation

Voting levels in national and state elections in the new republic had, in fact, never been high, not even in the years of greatest partisan contention. Only some sixty-two thousand voters—fewer than a third of those who were eligible—cast ballots for presidential electors in the pivotal election of 1800, and in all the presidential elections before 1828 the turnout of eligible voters never exceeded 42 percent.Glenn Altschuler 2001

Rude America - 19th Century Participation

Making material public can actually be a tactic to hide information by inundating people with too much to comprehend. Transparency, in short, can often be more for show than an actual revelation of substance.Katlyn Marie Carter 2023

Democracy in Darkness - Secrecy and Transparency in the Age of Revolutions

As Tocqueville remains so important a spokesman for the forcefulness of popular democracy in the Jacksonian era, let us note that the great writer returned to France without having observed a national election, and that in the notes he kept while traveling through America (and while speaking mainly to the most prominent members of American society) is Joel R. Poinsett’s answer to the question,” ‘Does the nomination for President excite real political passion?’ ‘No. It puts the interested parties into a grand commotion. It makes the newspapers make a lot of noise. But the mass of the people remain indifferent.’“ Indifference, too, is the theme of a letter written by Tocqueville’s traveling companion, Gustave de Beaumont, during their American visit. It is a letter that almost directly contradicts his friend’s appraisal of the penetration of politics into daily life. A people with so much free land, wrote Beaumont, “does not feel the slightest disposition to be discontent with the government. Each one, on the contrary, remains indifferent to the administration of the country, to occupy himself only with his own affairs.”Glenn Altschuler 2001

Rude America - 19th Century Participation

[In Greece] negotiations were exposed to the decisions, at once cumbrous and volatile, of a body of citizens, who were extremely ill-informed, subject to gusts of anger, sentimentality, fear or suspicion, inclined at any moment to reverse previous attitudes, and disastrously slow at coming to any decision.Sir Harold Nicolson 1953

The Evolution of Diplomatic Method

Things weren’t perfect in the old days. Hell, in 1952, there were 4 percent of the American people in a Gallup Poll that still thought FDR was president. But I think there was a moderately increased awareness of the basics of governance in those days. People had a little better idea of the Congress and the Supreme Court and the executive branch, and they understood the differences. They don’t anymore, because they’ve been pounded every day by people whose business it is to distort and confuse and to drive home a narrow, substantive viewpoint, rather than educating. So you don’t get Ed Murrow anymore; you get Rush Limbaugh, for Christ’s sake.Rep. Obey 2010

Obey Surveys the House (Politico)

Before assessing the impact of public perceptions of congressional candidates on individual vote choice and on electoral outcomes, I must first document what the public knows about the candidates. Donald Stokes and Warren Miller were impressed with how many voters in 1958 knew nothing at all about the candidates for the House of Representatives. Since the publication of their findings, no evidence has been presented to dispute the accuracy of this conclusion for the 1958 electorate or to support the view that the level of public information about congressional candidates has increased. The burden of proof is clearly on those who would argue that a significant part of the public is aware of the candidates. Mann 1978

Unsafe at Any Margin

Mass public knowledge of congressional candidates declines precipitously once we move beyond simple recognition, generalized feelings and incumbent job ratingsMann 1978

Unsafe at Any Margin

If nobody else cares about it very much, the special interest will get its way. If the public understands the issue at any level, then special interest groups are not able to buy an outcome that the public may not want. But the fact is that the public doesn’t focus on most of the work of the Congress. Most of the work of the Congress is very small things... And all of us, me included, are guilty of this: If the company or interest group is (a) supportive of you, (b) vitally concerned about an issue that, (c) nobody else in your district knows about or ever will know about, then the political calculus is quite simple. Rep. Vin Weber (R-Min) 1995

Speaking Freely (Schram)

Throughout the first 150 years of the federal government, access to government information does not appear to have been a major issue for the federal branches or the public.Austin Sarat 2018

Is full transparency good for democracy?

Transparency is not a viable substitute for regulation. Regulation is needed to ensure that the information disclosed through transparency is accurate and accessible. Moreover, transparency's effectiveness in achieving accountability requires conditions of civic and democratic engagement that do not hold in practice. When there are compelling reasons to advance a particular public good, transparency can help regulation but cannot replace it.Amitai Etzioni 2015

The Limits of Transparency

Citizens are not strongly attached to representative democracy’s processes and norms. Preferences for more participatory opportunities and democratic deliberation are shallow at best. Kathryn VanderMolen 2017

Reconsidering Preferences for Less Visible Government

Much has been written about public alienation from the public affairs process (Berman 1997), and the literature usually assumes that if only the right vehicle for empowerment and engagement were offered, citizens would lose their cynicism toward government and actively support democratic processes. However, theorists need to acknowledge that working out policy decisions and implementation details over a protracted series of meetings is an activity that most citizens prefer to avoid. Where communities are complacent, there is a strong argument for top-down administration simply on the grounds of efficiency. Lawrence and Deagen (2001) allude to this in their study of public participation methods, suggesting that in cases in which the public is likely to accept the mandate of an agency decision maker, a participatory process is not necessary. Williams et al (2001) show that, although members of the public indicated intent to participate, very few (less than 1 percent in their study) followed up by phoning for more information to join a participatory process. Members of the public might prefer to pay taxes to hire an astute public administrator to do the decision making rather than personally allocate the time to get involved in the governing process.Renee Irvin & John Stansbury

Citizen Participation in Decision Making: Is It Worth the Effort?

For obvious defensive reasons, the Continental Congress swore its members to secrecy, and initially none of its proceedings was officially published. These consisted largely of military plans, diplomatic feelers to European powers, and desperate efforts to raise funds. Even under wartime conditions, though, the trend was toward greater publicity... Periodic publication of congressional proceedings was inaugurated in 1777, and weekly publication became the rule in 1779. After 1781, ostensibly due to lack of public interest, the Articles of Confederation required only a monthly publication.Daniel N. Hoffman 1981

Government Secrecy and the Founding Fathers