60+ Academic Citations

Government Sunshine Drives Global Warming

Correlation doesn’t always equal causation. But with respect to climate change there is a correlation that has become difficult to ignore: Increased transparency during the drafting of environmental legislation, increases the chances that legislation will fail. The following citations show that this observation holds across time and place (countries, states, municipalities).

Some of this logic is clear. Increased transparency provides better hooks for powerful polluters to disrupt congressional action. Big oil spends far more to influence legislation than environmental groups, and their tactics are harsh. They fund challengers, attack ads, and opposition research – all of which terrorizes lawmakers. Petroleum groups fund misinformation campaigns - which make thoughtful legislation difficult even with respect to the electorate. As a result, moderate Republicans, even celebrated members like Bob Inglis, have found themselves taken out by faux ‘grass roots’ campaigns in their primaries. In short, the greater the access to the individual actions of our represenatives (greater transparency), the greater the chance those reps will be targetted by the attacks of big oil.

By James D’Angelo and Brent Ranalli – March 15, 2024

Citations

Below is a collection of citations that focus on the link between climate change and government transparency. To see more than a thousand citations that explain how lobbyists benefit from government transparency, click here.

Some of the key [climate] issues debated over the past 20 years were resolved in Paris in secret meetings.Radoslav S. Dimitrov 2016

The Paris Agreement on Climate Change: Behind Closed Doors

Manchin never heard from lobbies or [foreign] governments about the controversial part of the law because his team drafted it in secret. No one, save for senior Democrats in the Senate, knew they were drafting the measure. Once it came to light, and proved the saving grace for President Joe Biden’s climate agenda, the legislative process moved so quickly that no one had time to react.Alexander Ward and Susanne Lynch 2023

Manchin faces Europe’s wrath (Environment)

On Oct. 22, 2014 the Earth Institute hosted a panel discussion on the Origins of Environmental Law, featuring Leon Billings and Thomas Jorling, the two senior majority and minority staff members who led the Senate Subcommittee on Environmental Pollution which originated and developed the 1970s Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, and other major environmental/climate legislation... Jorling discussed the importance of the closed markup session – in the 1970s, laws were written behind closed doors, resulting in a high degree of cooperation. Senators were free to ask questions and discuss issues openly without fear of scrutiny from others. This created a lawmaking process built on “understanding, education and learning that members actively engaged in.” Today, the open session process in lawmaking makes for better theater than an actual practice of understanding.Haley Martinez 2014

Writers of the Clean Air Act: Insight into the ‘Golden Age’ of Environmental Law

The Paris outcome was made possible by the heavy use of secrecy. The agreement is a composite mélange of building block pieces, many of which were negotiated in secret over the two weeks and preceding months. Secrecy is common in diplomacy, but the French finessed it to a new level – and with compelling efficacy.Radoslav S. Dimitrov 2016

The Paris Agreement on Climate Change: Behind Closed Doors

Barbara Sinclair 2017 - Unorthodox Lawmaking - Voice Votes on Clean Air Act 1970

Note: Sinclair looks at how secrecy allowed for the straightforward passage of climate legislation in 1970. In comparison to today, the 1970s worked on legislation in closed committees with secret votes, today they are both open, driving hardlining and partisanship. To date, all effective climate legislation has benefit from important levels of secrecy. In other citiations on this page (and in her seminal book), she remarks how secrecy prevents capture by lobbyists and diminishes partisanship.

Barbara Sinclair 2017 - Unorthodox Lawmaking - Voice Votes on Clean Air Act 1970

The 1970 Clean Air Act was smooth, easy and important. It was mostly hashed out in secret, too.Michael Wines 1994 (NY Times Climate)

Who can govern while all those phones, faxes and focus groups are yelling?

The story of the passage of the [1970 Clean Air] Act would likely surprise even well-informed students of environmental legal history: many of its most important provisions were the product of tobacco-smoke-filled, closed-door deliberations filled primarily with decided nonenvironmentalists. In fact, some of its most significant innovations, such as national standards, came from the conservative Nixon Administration itself. Furthermore, the dedicated early enforcement of the Act, which made it legitimate and lasting, came by the hands of Nixon-appointees.Brigham Daniels, Andrew P. Follett & Joshua Davis 2020

The Making of the Clean Air Act (Climate)

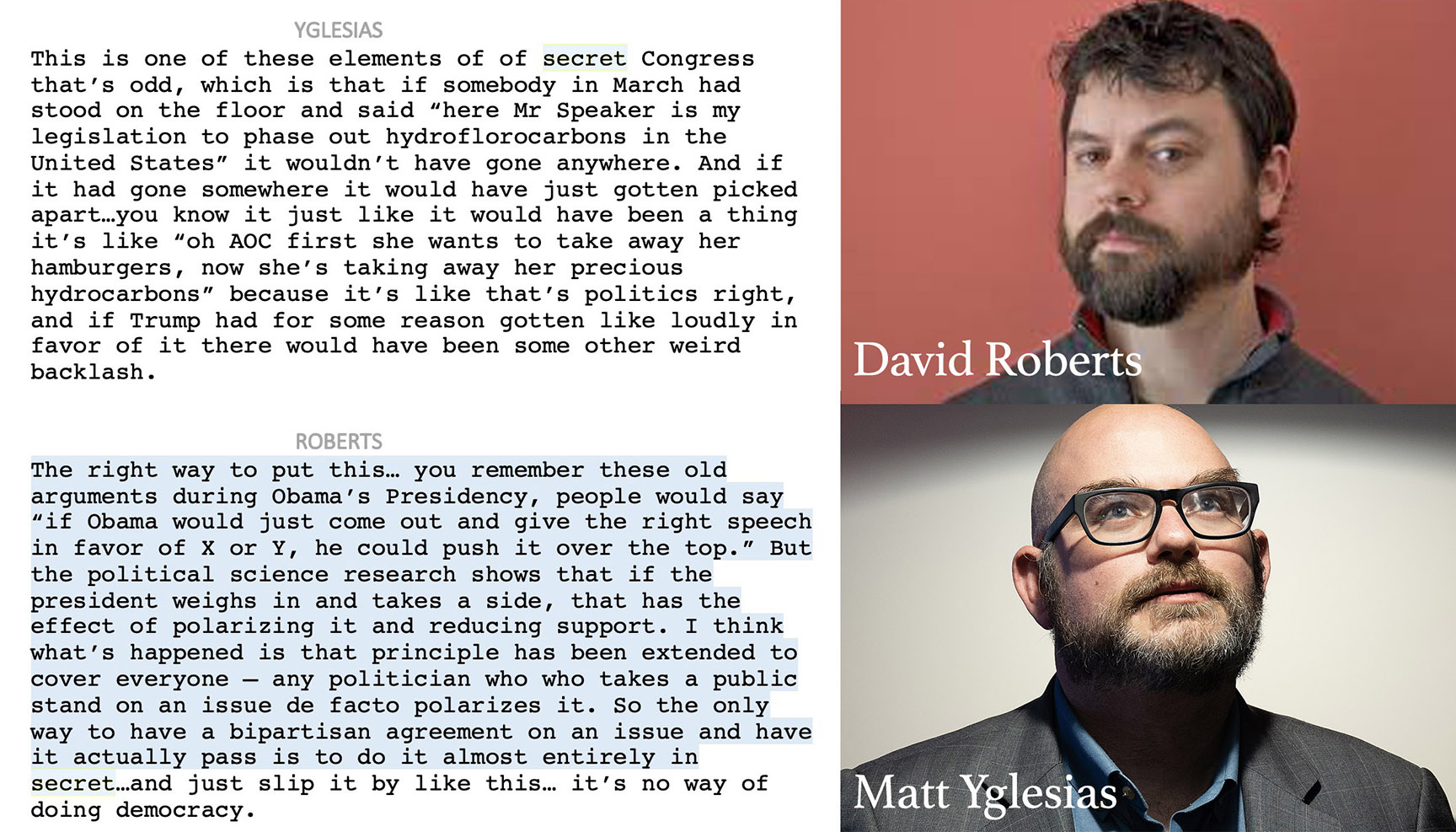

David Roberts & Matthew Yglesias 2020 - The Climate and Secret Congress

Text: YGLESIAS This is one of these elements of of secret Congress that’s odd, which is that if somebody in March had stood on the floor and said “here Mr Speaker is my legislation to phase out hydroflorocarbons in the United States” it wouldn’t have gone anywhere. And if it had gone somewhere it would have just gotten picked apart…you know it just like it would have been a thing it’s like “oh AOC first she wants to take away her hamburgers, now she’s taking away her precious hydrocarbons” because it’s like that’s politics right, and if Trump had for some reason gotten like loudly in favor of it there would have been some other weird backlash. ROBERTS The right way to put this… you remember these old arguments during Obama’s Presidency, people would say “if Obama would just come out and give the right speech in favor of X or Y, he could push it over the top.” But the political science research shows that if the president weighs in and takes a side, that has the effect of polarizing it and reducing support. I think what’s happened is that principle has been extended to cover everyone – any politician who who takes a public stand on an issue de facto polarizes it. So the only way to have a bipartisan agreement on an issue and have it actually pass is to do it almost entirely in secret…and just slip it by like this… it’s no way of doing democracy.

David Roberts & Matthew Yglesias 2020 - The Climate and Secret Congress

Many Republicans will say privately that they understand the science, but if they talk about climate change publicly they will prompt a primary challenge from the right — so they stay quiet, at best, or join the obstructionists in questioning the science. There has been no major change in climate science since 1979; what has changed is the politics.William K. Reilly 2018

The Term “Republican Environmentalist” Is Not an Oxymoron

A common feature of these informal arrangements is that all of them have taken shape behind closed doors, with party leaders controlling the process. In at least one aspect, therefore, Wilson’s portrayal of Congress remains valid. “One very noteworthy result of this system,” he wrote, “is to shift the theater of debate upon legislation from the floor of Congress to the privacy of the committee rooms.”Richard Cohen 1990 (Climate)

Crumbling Committees

Then, too, Senator Muskie had to be concerned with attracting Republican support. He faced a dilemma. On the one hand, he had to outdo President Nixon in order to preserve his environmentalist credentials43—Ralph Nader, then at the height of his influence, had blasted Senator Muskie for not being aggressive enough44—and thus help him remain the leading candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1972. On the other hand, Senator Muskie needed to develop a bill with enough bipartisan support that it could make its way through the Senate and House. So, he worked with Republican and Democratic members of his subcommittee behind closed doors—this was before the congressional reforms adopted after Watergate—to satisfy them.Craig N. Oren 2016

Struggling for Context: An Appraisal of “Struggling for Air” (Climate)

The Mitchell-sponsored talks were conducted behind closed doors and they spurned roll-call votes that would have revealed the legislative divisions. Mitchell believed, probably correctly, that senators would not get down to hard negotiating on environmental issues so long as they were in the public spotlight, where they might make statements that a political opponent could use against them. The closed-door meetings also allowed senators to ask questions and to educate themselves about often complex issues in a way that might have proved embarrassing in front of a television camera.Richard Cohen 1994

Washington at Work: Back Rooms and Clean Air (Climate)Note: This citation refers to the passage of the 1990 Clean Air Amendments (the most powerful environmental/climate legislation in the past 40 years), which were brokered almost exclusively behind closed doors by Mitchell and others expressly to avoid the pressure of lobbyists. Full citation can be found here.

Richard Cohen 1993 - Washington at Work: Back Rooms and Clean Air (Climate)

Richard Cohen 1993 - Washington at Work: Back Rooms and Clean Air (Climate)

The House Committee on Public Works, for example, had about six staffers assigned to the 1972 Clean Water Act. One of them, Gordon Wood, remembers an intimate process that enabled compromise... He said closed-door meetings enabled lawmakers to take off “their blue shirts and red neckties.”Emily Yehle 2014

Recalling the long, hard slog to a ‘Historic piece of legislation’ (Climate)

Meetings occur behind closed doors so lawmakers can escape pressures from lobbyists and reporters, who have made it more difficult for them to handle business “in the sunshine.”Richard Cohen 1994

Washington at Work: Back Rooms and Clean AirNote: This citation refers to the passage of the 1990 Clean Air Amendments (the most powerful environmental/climate legislation in the past 40 years), which were brokered almost exclusively behind closed doors by Mitchell and others expressly to avoid the pressure of lobbyists. Full citation can be found here.

To speed progress [of the 1990 Clean Air Act] much of the negotiations during mark-up proceeded behind closed doors. On 22 March 1990 members emerged to report that a compromise had been agreed on urban smog which divided the worst polluted area of the country into categories based on the severity of their pollution and established methods to bring them into compliance with health standards.Christopher J. Bailey 1998

Congress and Air Pollution (Climate)

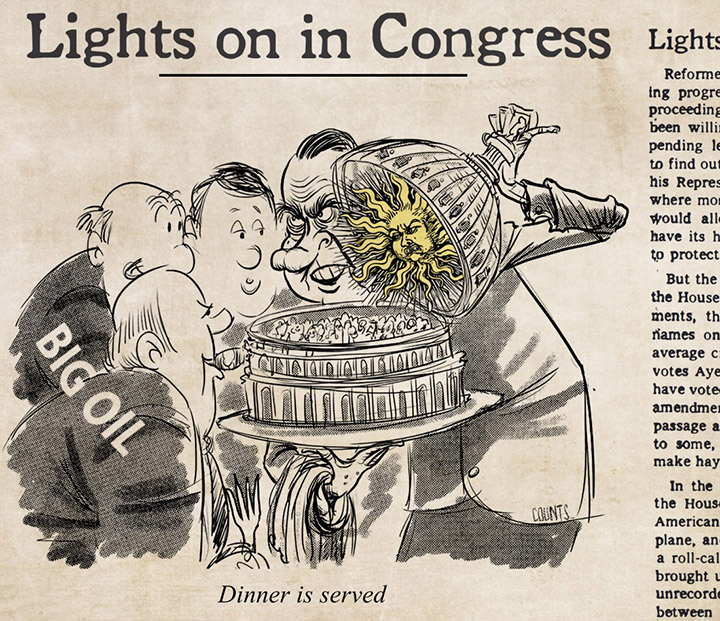

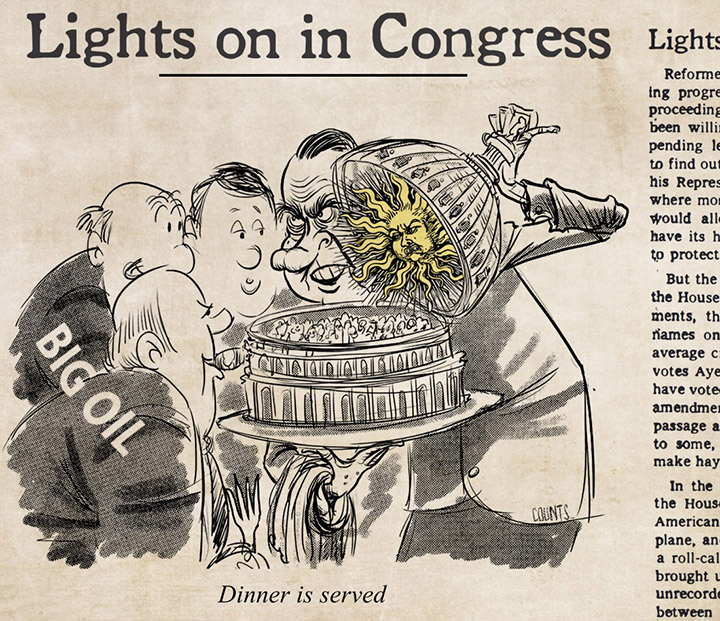

Dave Counts - Dinner is served

In 1970, President Nixon signed The Legislative Reorganization Act opening congressional committees to the glare of powerful interests - especially Big Oil.

Dave Counts - Dinner is served

Although [George] Mitchell and Baucus believed that a majority of senators would vote for the Committee bill [on the 1990 Clean Air Act], they did not believe that they had sufficient votes either to invoke cloture if someone like Senator Byrd decided to filibuster the measure or to override a potential presidential veto. They decided as a result to work with the Administration to produce a compromise. A month of negotiations followed in which Mitchell and Minority Leader Dole, a few members of the Environment and Public Works Committee, EPA officials and White House officials led by Roger B. Porter met behind closed doors to fashion legislation acceptable to both sides. The result was a substitute bill that steered a middle line between the original Committee and Administration bills. It phased in automobile exhaust emission reductions, mandated a study of the best way to assess the health risk of air toxics after MACT had been installed, and provided midwestern utilities with extra sulphur dioxide ‘allowances’ which could be sold to defray the costs.Christopher J. Bailey 1998

Congress and Air Pollution (Climate)

What is striking about the making of air pollution policy in the European Union, however, is that while it has undoubtedly been a difficult process, the Council of Ministers has been able to arrive at compromises and adopt legislation far more easily than has the U.S. Congress. Legislation addressing the issue of acid rain and vehicle emissions was agreed to far more quickly than was the Clear Air Act of 1990. Those attributes that the U.S. Congress adopted to make the compromises that ultimately led to success – secrecy, bargains, and side payments – have been intrinsic to the way the Council of Ministers works.Alberta Sbragia 2004

The United States and the European Union Compared (Climate)

For a striking example of how the public and Congress as a whole can be kept in the dark about significant policy conflicts, one need look no further than to the long-drawn-out mark up and conference sessions on the 1972 water pollution act. Important policy questions were being debated: the amount of money needed for pollution abatement; the right of citizens to bring mandamus actions against complacent pollution control agencies; and the question of zero discharges of pollutants as a policy goal. Yet the House Committee on Public Works held mark-up sessions over a period of 3 months, all in closed session, with no official information given out until the pollution control bill was finally reported-2 weeks before the House acted on it.Luther J. Carter 1973

Secrecy in Congress: Tiptoeing toward Reform (Climate)

On the libertarian right, FOIA is celebrated as a means to impede “the Statists” at disfavored agencies through “witch hunts” and “fishing expeditions.” The conservative Judicial Watch foundation came to prominence over the past two decades largely by using FOIA to “trip up” Democratic officials. Freedom Watch now plows the same ground. There is no comparable outfit (Civic Solidarity Watch?) on the progressive left. In the environmental area, FOIA-fueled witch hunts and fishing expeditions have become so serious that a legal defense fund was established in 2011 to help climate scientists fend off “malicious freedom of information act requests.” These oppositional uses of FOIA not only exacerbate diversion and deliberation costs but also alter the political sociology of agency action, making it harder for administrators to formulate and carry out affirmative agendas of all kinds.David Pozen 2017

Freedom of Information Beyond the Freedom of Information Act

Rep. Henry Waxman 2009 – How Congress Really Works (Tobacco and Pesticides)

TEXT: he problem of what to do about pesticides had frustrated Congress for almost two decades, until members of my staff and the staff of Tom Bliley, a Virginia Republican, met secretly… One group absent from the proceedings was lobbyists. But having found common purpose on other seemingly intractable problems, we decided to give tobacco a try, too. Our negotiations for a comprehensive tobacco bill followed the same model as they had for the pesticide measure, utter secrecy of the proceedings guaranteeing both sides the political cover necessary to explore compromises. Only Newt Gingrich, the Republican speaker of the house, and Richard Gephardt, the Democratic minority leader, were kept apprised. (Environment / Climate analagous)

Rep. Henry Waxman 2009 – How Congress Really Works (Tobacco and Pesticides)

HOST MICHAEL GERRARD: I was struck by your description of the legislative process being largely behind closed doors and that there is a tension there, between that and the usefulness of that, and transparency. as you were just speaking about Mr. Jorling. So how does that function? Is there a sweet spot at which members need privacy to have these questions? Have we become too transparent?

TOM JORLING: Well, when we do talk about the differences between then and now one of, to me, is the most significant is the closed markup. The transparency comes because it’s going to be on the floor, [the bill] it’s going to be debated and it’s going to be voted upon. But the opportunity to learn and to dig deeply into a subject can’t be done in open forum. It’s as if you would put cameras in there which would automatically lead to people starting to play to their base and no longer be interested in trying to come up with a meaningful set of answers to difficult questions. It’s absolutely essential that they [legislators] have that that space to do that [debate and consider]. And I’ll mention one more thing and then Leon [Billings] can join. Senator Muskie had a very important method to developing legislation. If we would present what we thought were answers to some of the difficult questions, he would undertake to question us in the most aggressive and hostile ways, because his theory was if I can’t, if you can’t answer these questions, I can’t answer them on the floor when this matter gets into that part of the process. No one could do that if it was in open session and the cameras were there and the base was out there responding. He sort of taught that method to all of them because they all became adept at pressing us on whether or not what they were being asked to review or consider was meritorious. They would ask the most difficult questions that they could and if they didn’t get satisfactory answers they would send us back to the drawing board. So it [secrecy] was a very essential part. It also was an important part of the respect, if you would portray this fast forward [Senator] Eagleton and [Senator] Baker probably would have been aggressive contestants with each other if they were doing everything in public, but because they were in this space. They could challenge each other they could learn what was motivating each other it led to a kind of understanding that they weren’t out to try and game one another but rather to solve a public policy question. So I think it’s immensely important. I think the greatest result or the greatest poor result of Watergate was to quote reform the processes and they reformed them in a number of ways including to open up markups, but those reforms I think have been very damaging to the legislative process.

LEON BILLINGS: Senator Muskie was one of the leading advocates of sunshine laws. He opened one of his other subcommittees, where he had the authority to do that, early on in the process - and he was very strongly for that. And he found out, almost immediately, that some of the members couldn’t work well in that fully open environment. You see it now [2014] with this budget agreement that was just reached two-year budget agreement crafted in private, no public participation, no public gazing on the process came out and revealed it. Same thing happened three years ago four years ago in the 2011 debt extension legislation. So the congress is drifting back to that there it’s not the same committee structure that they had but clearly where comity is being achieved in the current political environment it’s being achieved behind closed doors not in open session.Leon Billings & Tom Jorling 2014

Interview on 1970 Clean Air Act - Benefits of Closed Door Sessions (Climate)

Surprisingly, we found transparency had no significant effect in almost any of our quantitative measurements, although our qualitative results suggested that when transparency interventions exposed corruption, some limited oversight could result. Our findings are particularly significant for developing democracies and show, at least in this context, that Justice Brandeis may have oversold the cleansing effects of transparency. A few rays of transparency shining light on government action do not disinfect the system and cure government corruption and mismanagement.Brigham Daniels, Mark Buntaine & Tanner Bangerter 2020

Testing Transparency (Climate)

Sanho Tree 2015 - Straw Polls, Secret Voting, and the Pitfalls of Accountability

EXCERPT: I think one of the ways to do that, again, it’s very counterintuitive, is that there’s too much accountability for politicians. Before you freak out and think I’m crazy, let me give you an example of what I mean by that. Oscar Wilde once said, “If you want someone to tell you the truth, give them a mask.”... So if you were able to do a (secret straw poll) survey in Congress today and it turned out that, say, two-thirds wanted to tax and regulate cannabis, if you release the aggregate number, the result of that, no names attached, just that in aggregate two-thirds of Congress actually believes this, then that gives some political cover for politicians to stand up and do the right thing, the courageous thing. They can say, “Look, I’m actually being courageous by saying publicly what my colleagues all believe privately – that it’s time we change our policies on this issue.” And I think that’s a way to solve a lot of third rail issues in Washington. We’re running out of time, both me and Congress, to deal with very serious issues, things like climate change, sensible gun control, or other issues that are controversial politicians cannot deal with. They’re paralyzed because they’re pinned down by these gotcha votes.

Sanho Tree 2015 - Straw Polls, Secret Voting, and the Pitfalls of Accountability

Subcommittee deliberations [on the 1970 Clean Air Act] took place in the ironically smoke-saturated, mid-sized Public Works Committee conference room, number 4200, in the New Senate Office building, also known as the Dirksen. These meetings were out of the public eye and off record, though stenographic notes were taken—a number of which, but not all, still survive... It was an era in which ten or eleven men... sat around in a closed room and talk about what public policy ought to be, without the influence of lobbyists and damn little influence of staff... Somehow, surrounded by the haze of their own smoke and tucked away from a progressive youth movement, this demonstrably homogenous and institutionalist collection of legislators, embodying uncontested privilege in America, worked out the fundamental piece of U.S. Code which would make significant progress in cleaning the air and protecting millions of Americans’ health and well-being.Brigham Daniels, Andrew P. Follett & Joshua Davis 2020

The Making of the Clean Air Act (Climate)

The ‘deal’ on climate policy between the Liberals and Nationals, between Scott Morrison and Barnaby Joyce, will see Australia formally commit to a target of reaching net zero emissions by 2050…Barnaby Joyce and the Nationals did not want to sign onto a net zero deal without significant concessions for the regions…It appears Scott Morrison has given away little to the Nationals to secure their support for the net-zero-emissions-by-2050 target. Of course, it is not entirely clear, given negotiations were conducted behind closed doors.Melissa Clarke 2021

Scott Morrison yields little but wins little in net zero support

It is important, as we review the Muskie legacy, to understand several things: First, as I noted before, there were no federal laws of any kind on any subject which had deadlines, statutory standards, mandatory requirements or citizen enforcement rights. There was very little opportunity for the public to participate in policy decisions. There was very little government outreach. There was very little sunshine, a lot of darkness, and most public policy was at the discretion of the political appointees or bureaucrats. Second, consensus was a more effective tool for advancing public policy than was a confrontation. Members of Congress, House and Senate, actually got things done by working with their colleagues across the aisle. It was commonplace to have major policies cosponsored by members of both parties. Third, before 1973, the Committees of the Congress met behind closed doors. The concept of open decisions openly arrived at simply didn't exist. Fourth, there were very few "lobbyists" - people who plied the trade of influencing Members of Congress on behalf of specific clients. That is not to say they didn't exist. There just weren't that many. Fifth, campaigns were financed very differently. Senator Muskie's last campaign for United States Senate, in 1976, cost less than $160,000. Senator Muskie spent virtually none of his time raising money or calling contributors. He literally hated asking for money. While he had done that to a degree when he was a candidate for President, even then most of the fundraising was done by third parties. Sixth, political action committees, as we now know them, didn't exist. Business contributions to Members of Congress came from the pockets of the businessmen themselves, not their political committees. Corporate money could not be spent to create PACs and corporations could not contribute to federal campaigns (or to state campaigns in 22 states). It was the philosophy of elected Members of the Senate and the House which dictated the nature of the legislative initiative rather than the influence of the special interests who had endeared themselves to a Member through campaign largesse. Seventh, there were very few staff. The initial work by the Air and Water Pollution Subcommittee was done with personal staff assisted by bureaucrats seconded from the Public Health Service. The contributions of the Senator's Administrative Assistant Don Nicoll and his colleague Caleb Boggs' (R-DE) legislative assistant Bill Hildenbrand was critical to his early success. The 1970 Clean Air Act was the product of staff work of no more than 15 people and most of the staff recommendations were the responsibility of four key staff. Members were Members; staff were staff. And we were frequently reminded if we forgot the distinction.Leon J. Billings 2005

The Muskie Legacy (Climate)

Michael Bosse 2018 – George Mitchell - Maine’s Environmental Senator (Climate)

Michael Bosse 2018 – George Mitchell - Maine’s Environmental Senator (Climate)

Frontline 2012 - Climate of Doubt

Note: Bob Inglis was a revered Republican congressman and a presidential hopeful, until he began to address climate change. Big oil (Tea Party) destroyed him in the primaries via negative ads that had little to do with climate. This terrifying message reverberates still through all modern day Republican primaries - “make a move on climate change you moderate Republican and big oil will gun you down!” Given that all of Inglis’ congressional votes and committee actions were required to be public actions, he had little alternative but to address the problem of climate head on. But in years past this wasn’t the case. Republicans were able to vote secretly about climate issues in both 1970 and 1990 and powerful environmental laws were passed. Ironically, global warming may be the the result of too much congressional sunshine.

Frontline 2012 - Climate of Doubt

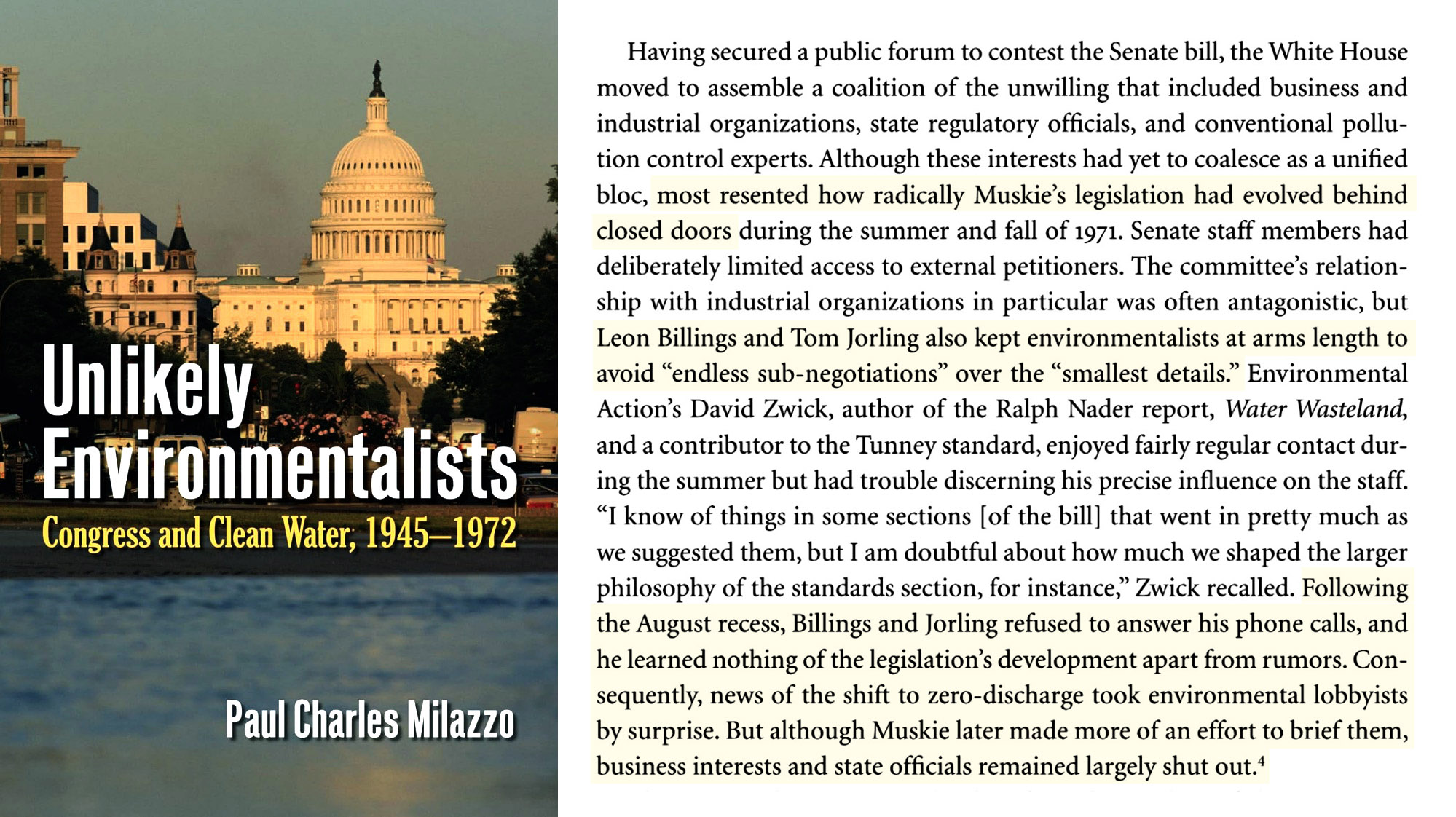

In the early seventies, Public Works Committee staffers conceived some of the Clean Water Act’s more radical features and helped channel the ecological knowledge that inspired them. Even so, the final product grew out of an extended conversation among the senators themselves behind closed doors. During their colloquy, they vetted the feasibility of the legislation’s objectives…Party affiliation certainly colored individual opinions, but the senators’ cooperative efforts and collective identity as legislative policy specialists tended to trump partisan differences. The result was a water pollution bill whose content surprised both sides of the political divide… Yet, much to his chagrin, in 1972, Muskie found himself defending the Clean Water Act’s provisions from both its foes as well as its putative friends.Paul Charles Milazzo 2016

Unlikely Environmentalists: Congress and Clean Water, 1945 - 1972 (Climate)NOTE: This next citation is from book introduction and highlights how legislative action preceded public action: “Environmental activism has most often been credited to grassroots protesters, but much early progress in environmental protection originated in the halls of Congress. As Paul Milazzo shows, a coterie of unlikely environmentalists placed water quality issues on the national agenda as early as the 1950s and continued to shape governmental policy through the early 1970s, both outpacing public concern and predating the environmental movement.”

[Fearful of lobbyists from both sides of the issue, members wrote environmental policy behind] closed doors during the summer and fall of 1971. Senate staff members had deliberately limited access to external petitioners. The committee's relationship with industrial organizations in particular was often antagonistic, but Leon Billings and Tom Jorling also kept environmentalists at arms length to avoid “endless sub-negotiations” over the “smallest details.”Paul Charles Milazzo 2016

Unlikely Environmentalists: Congress and Clean Water, 1945 - 1972 (Climate)NOTE from book introduction: Environmental activism has most often been credited to grassroots protesters, but much early progress in environmental protection originated in the halls of Congress. As Paul Milazzo shows, a coterie of unlikely environmentalists placed water quality issues on the national agenda as early as the 1950s and continued to shape governmental policy through the early 1970s, both outpacing public concern and predating the environmental movement.

I was calling in simply because I had been for a long time, the minority staff director of one of the congressional committees and I was going to offer a comment on this issue of open versus closed meetings. Prior to the adoption of the rule requiring open markups and open conferences, I think that the process of a executive session for the consideration of a bill was a far more meaningful process because the members came in and really, honestly debated many of the issues. Whereas, I think today the tendency is to resolve most of the more controversial questions before you get to the markup. And it in turn becomes almost a pro-forma show for the audience without any real serious hard give-and-take among the members when they're standing there in front of the audience. They're playing to the audience. Whereas in a closed session, they tended to really be addressing each other seriously on the issues. I can recall back when, for example, we held markups on some of the early environmental laws on NEPA, for example, the Endangered Species Act and various other environmental bills. This is in the house Merchant Marine Committee. If we had been having an open session it would have been a disaster.CSPAN caller

Jacqueline Calmes 1987 Closed Door Meetings C-SPAN (Climate)

In this climate, the first nationwide air pollution standards were crafted with Billings, typewriter at the ready. Provision by provision, negotiated behind closed doors – as was legal then – with Democrats and Republicans.Jayme Fraser 2016

Progressive era inspired Clean Air, Clean Water acts (Climate)

Most important — and completely ignored by the champions of transparency — is the fact that even the most conscientious citizens, dedicated to following public affairs, have but one vote to weigh in on myriad issues. Most of the time, citizens cannot vote up or down any specific program. Exceptions include some local or state initiatives, such as bonds for schools or referenda on social issues like gay marriage. However, most of the time, especially at the national level, voters cannot be in favor of, say, much more funding for climate change, only a little more funding for ocean exploration, and less funding for bombers (or any such other combination). Rather, all they can do is vote up or down their representative, who, in turn, votes on many scores of programs. Amitai Etzioni 2014 – Atlantic

Transparency is Overrated

Aaron Strauss 2022 Secret Congress and the Environment (Climate)

Aaron Strauss 2022 Secret Congress and the Environment (Climate)

All three approaches combined to form the Clean Air Act, as the legislation came to be called. What would it take, Muskie asked, for an automobile not to pose a threat to the public’s health? One answer, provided by the director of the National Air Pollution Control Administration, was to reduce its emissions by 90 percent. Liking that answer, Muskie modified the (Climate) bill to require carmakers to reduce toxic emissions by 90 percent in their 1975 and 1976 models—much sooner than anyone had expected. Urged on by Muskie and Baker, the members of the subcommittee approved the more stringent requirements. The vote, like the meetings, was held behind closed doors, which was standard procedure at the time.Susan Dudley Gold 2012

Clean Air and Clean Water Acts

CQ 2013 – How Congress Works

Note: In 1990, Mitchell passed the most significant environmental/climate legislation since the late 1960s. And in order to do it, he reversed the notions of the 1970s transparency.

CQ 2013 – How Congress Works

Part way through the meeting [committee meeting on the 1970 Clean Air Act], minority counsel Tom Jorling left the meeting room to use the restroom. On this occasion, he was followed by one of the technical people from General Motors. While standing next to each other at the urinal, the man confided to Jorling: “We can build whatever you tell us to build. If you tell us to build a clean car, we will build a clean car.” There were other instances where manila envelopes were sent anonymously to the Subcommittee with internal documents that undercut positions industry representatives had made to the Committee. Interactions like these did not do any favors for the auto companies.Brigham Daniels, Andrew P. Follett & Joshua Davis 2020

The Making of the Clean Air Act (Climate)Note: Even those who worked for the auto industry wanted cleaner air and were willing to take risks (secretly) to let the legislators know. Clearly they were terrified of thier bosses - GM etc.

This summer’s efforts by White House and congressional budget summiteers to force deep cuts in the deficits have largely preempted the jurisdiction of congressional committees, notably the tax-writing panels. Although the members of the House Ways and Means and Senate Finance Committees would probably have a major voice in writing the details of any tax bill that emerges from a summit deal, they have already largely relinquished their authority to make the broad decisions. Their chairmen-Rep. Dan Rostenkowski, D-Ill., and Sen. Lloyd Bentsen, D-Texas have consented to arrangements that allow a wider group of Members to craft tax policy. “All Members see (raising taxes) as a tar baby, and they want to get rid of it,” a close observer said.

The Senate version of the clean air bill was drafted early this year during a monthlong series of meetings convened and masterminded by Senate Majority Leader George J. Mitchell, D-Maine. The meetings were held in Mitchell’s office, with key Senators and Bush Administration officials attending. This extraordinary step was taken after it had become clear that the Senate would never approve the legislation written by the Environment and Public Works Committee because of the opposition of the Administration and powerful private interests. Even in the House, where the bill was handled largely by the Energy and Commerce Committee, most of the major issues were resolved privately by the committee’s leaders, sparing the full committee and the House from the potentially painful task of choosing sides.

The Senate version of a comprehensive anticrime bill, which was approved in July, came to the floor despite the almost total absence of debate or formal action by the Judiciary Committee and with most of the important decisions made off the floor by party leaders. In the House, where the rules give the majority party added leverage, Judiciary Committee Democrats worked with party leaders on their own of the bill, which has been sent to the floor.Richard Cohen 1990

Crumbling Committees (Climate)

So where a chamber of the legislature voted against the considered opinion of the people — as represented by a substantial majority of the citizens’ assembly — that assembly could require the chamber to vote again, this time by secret ballot. Had we had such a system in 2013, Australia would not have stumbled into the disastrous climate change policy it has today and, as I’ve argued, Britain would be navigating its numerous and ongoing Brexit dilemmas more conscientiously. Meanwhile, in the US, the Senate might have structured its verdict on the 45th president as a procedural vote followed by a substantive vote. The first procedural vote would be by open ballot, and would determine by a simple majority whether the substantive vote should be by open or secret ballot.I think a majority would have voted for a secret ballot and, having loosed the vice-like grip of party discipline, would have struck a blow for true accountability rather than its tawdry simulacrum.Nicholas Gruen 2021

Saving democracy: one secret ballot at a time

Paul Milazzo 2006 - Unlikely Environmentalists: Congress and Clean Water, 1945 - 1972 (Climate)

[Fearful of lobbyists from both sides of the issue, members wrote environmental policy behind] closed doors during the summer and fall of 1971. Senate staff members had deliberately limited access to external petitioners. The committee's relationship with industrial organizations in particular was often antagonistic, but Leon Billings and Tom Jorling also kept environmentalists at arms length to avoid “endless sub-negotiations” over the “smallest details.”

Paul Milazzo 2006 - Unlikely Environmentalists: Congress and Clean Water, 1945 - 1972 (Climate)

At a Rose Garden ceremony on May 19, 2009, President Obama announced an “historic agreement” between automakers, the International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America (UAW), the State of California, and the Obama Administration to set fuel economy/ GHG standards through 2016, hereinafter referred to as the “historic agreement.” Unfortunately, this agreement is quite literally the product of secret, closed door negotiations, led by Assistant to the President for Energy and Climate Change, also known as the Energy and Environment Czar, Carol Browner. According to the New York Times, Ms. Browner imposed a “vow of silence” over the negotiations on vehicle fuel economy [standards]. California Air Resources Board Chairman Mary Nichols even bragged that “We put nothing in writing, ever.” Due to this unusual imposition of secrecy, any conversations between individuals in the automobile industry and members of the Administration, which led or contributed in any way to the historic agreement, shall be hereinafter referred to as the “secret negotiations.”Representative Darrell E. Issa & Lamar Smith 2010

Request for Information on Secret Negotiations (Climate)

Judith Layzer & Sara Rinfret 2023 - The Environmental Case (Climate)

Text: To facilitate negotiations among members of this fractious group, nearly all of the committee meetings were conducted behind closed doors and often at night. Like Mitchell in the Senate, Dingell hoped to spare rank-and-file lawmakers the constant pressure to serve constituent demands by freeing them from the speechmaking and position-taking associated with public hearings on controversial legislation. The “dirties” and “cleans” finally agreed on a compromise in which Midwestern utilities got more time to reduce emissions, additional emissions allowances, and funds to speed development of technology to reduce coal emissions. Members from the “clean” states extracted some concessions as well: they obtained greater flexibility for their utilities under the trading system, and they got all the allowances the Midwesterners initially had been reluctant to give them.

Judith Layzer & Sara Rinfret 2023 - The Environmental Case (Climate)

After a decade of delay, the Clean Air Act Amendments passed by overwhelming majorities in both chambers, making manifest both the power of well-placed opponents to maintain the status quo against a popular alternative and the importance of legislative leaders in facilitating a successful policy challenge… Congressional leaders, particularly Mitchell and Dingell, brokered deals that were crucial to building a majority coalition. Their willingness to hold meetings behind closed doors, away from the scrutiny of lobbyists, was particularly crucial.Judith A. Layzer & Sara R. Rinfret 2023

The Environmental Case (Climate)

Mediators may wish to make use of opportunities for informal exchange as a way of getting things unstuck. If the formal process of offer and counteroffer, as it takes place at the negotiating table, is being used to state extreme positions in public, and the disputants have reached an impasse, it may be wise to create opportunities for more informal arrangements. UNEP Executive Director, Mustafa K. Tolba, appears to have done just this during the Montreal Protocol negotiations on the depletion of the ozone layer. Tolba made extensive use of “informal consultations” designed to help narrow the gap between the divergent views of negotiators on central issues, and accomplished this away from the plenary session. (Climate and Environment)Gunnar Sjostedt 1992

International Environmental Negotiation: Insights for Practice

Agence France-Presse 2021 – World leaders and UN to hold closed-door climate talks

Agence France-Presse 2021 – World leaders and UN to hold closed-door climate talks

The value of secrecy was in reducing the number of actors, widely recognized as an obstacle in negotiations...Some of the key issues debated over the past 20 years were resolved in Paris in secret meetings among a few countries. Six working groups on the key issues were established during the second week. One of them concluded its work without a single formal session because everything was settled privately. I participated in a small “invisible” meeting regarding a secret deal between the US and Saudi Arabia. The meeting took place in a small room of 5 by 5 meters, among only 10 individuals. My delegation was asked to accept or reject the bilateral deal, without rights to negotiate or modify. No record was kept, there was no paper copy of the legal text in question that was only displayed on a small screen, and we were explicitly told not to take photos. We endorsed the deal, and so did other ‘key players.’Radoslav S. Dimitrov 2016

The Paris Agreement on Climate Change: Behind Closed Doors

Previous studies have noted that states prefer to close negotiations when the issues under discussion are sensitive (Depledge 2005; Raustiala 1997; Stasavage 2004).Naghmeh Nasiritousi & Björn-Ola Linnér 2016

Open or closed meetings? Explaining nonstate actor involvement in the international climate change negotiations

Secret negotiations were a motif this week. U.S. and Chinese negotiators began meeting last July trying to bridge their differences on emissions reductions, symbolically at the Great Wall. The Guardian broke news of the meetings on Monday, reporting that senior Bush administration advisers and several current Obama advisers met with Chinese officials. The back-channel talks led in March to an unsigned memorandum of understanding, which participants hope will embolden the world’s two largest national emitters to find a common ground in addressing the causes of climate change.Josh Wilson 2010

Scaling the Great Wall of Climate Change

Nearly 80% of the 108 Climate Assembly UK members agreed in a secret ballot that government steps to boost the economy should be designed to help achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 — a target enshrined in British law last year.Megan Rowling 2020

UK Citizens’ Assembly on Climate Change Backs a Green Coronavirus Recovery

Conversations between assembly members are private and never live streamed to ensure they feel able to have full and frank discussions.Climate Assembly UK 2020

The Path to Net Zero

It is no secret that negotiations are best done in private. James Madison remembered that, in writing the Constitution [and] the same principles of successful negotiation hold more than two centuries later. Examples of the White House and Congress strategically engaging in quiet negotiations to produce important legislation include the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990, the budget agreement of 1990, and the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001… Low-keyed, good-faith negotiations began shortly after the president submitted his FY 1998 budget, and senior White House officials held a series of private meetings with members of Congress. Unlike the political posturing in late 1995 and early 1996, neither side focused on moving the negotiations into the public arena.

Staying private made it easier for both sides to compromise, and they each gained from doing so. For Republicans, the budget agreement capped a balanced-budget and tax-cutting drive that had consumed them since they had taken over Congress in 1995. They won tax and spending cuts, a balanced budget in five years, and a plan to keep Medicare solvent for another decade. Thus, although they did not achieve a radical overhaul of entitlement programs, they did make substantial progress toward their core goals… The decision of President Clinton and the Republican congressional leaders to seize on the opportunity provided by the surging economy and the groundwork laid by the budgets of 1990 and 1993 and to quietly negotiate and compromise, letting everyone claim victory, made the budget agreement possible.George C. Edwards 2015

Staying Private - Solutions to Polarization (Climate, Persily)

The same principles of successful negotiation [via secrecy] hold more than two centuries later. Examples of the White House and Congress strategically engaging in quiet negotiations to produce important legislation include the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990, the budget agreement of 1990, and the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001.George C. Edwards 2015

Staying Private - Solutions to Polarization (Climate, Persily)

Matthew Yglesias 2023 Secret Congress Delivers More Good News on Clean Water

Note: Climate legislation of both the IRA (Inflation Reduction Act) and NDAA (National Defense Authorization Act) had high levels of secrecy to prevent lobbying - even from foreign governments, etc - and to prevent the standard political backlash for any publicly announced environmental legislation.

Matthew Yglesias 2023 Secret Congress Delivers More Good News on Clean Water

All Congress used to be “secret.” When a piece of legislation receives a lot of coverage, that coverage is likely to be tilted in a negative direction. It’s simply not possible to have a bill that makes any kind of meaningful changes that doesn’t generate some complaints — either from people who don’t like the changes or else from people who think the changes don’t go far enough...the main thing to remember is that in the pre-internet era, Secret Congress was the norm — there just wasn’t that much national news coverage (22 minutes per night on network television), and a lot of that coverage wasn’t political. People got their information through locally focused outlets that mostly weren’t in very competitive markets, so you’d get stories about interesting scandals but not a lot of gripping white-knuckle coverage of actual legislation. That didn’t mean members would always reach agreements on things, but it did mean that if they wanted to reach an agreement, they could do so in relative obscurity and then announce it to the world...The news flow you’re exposed to is very disproportionately negative, both because negative stories are more likely to be written but also because the people who you follow on social media are more likely to share them, and also because you yourself are frankly more likely to click on them.Matthew Yglesias 2022

Secret Congress delivers more good news on clean waterNote: Yglesias is oddly missing a lot of historical context on the benefits of secrecy. So he kind of gets it, but without all the proper backdrop, he is missing the full power of his ideas. James D'Angelo respond to him, addressing some of this issue, here in this tweet. Secrecy appears to be essential to climate and environmental legislation.

If reverse FOIA effectively shrinks the Act’s disclosure mandate in an industryprotective manner, a late-1990s revision expands it toward the same end. The Shelby Amendment (named after its Senate sponsor) provides that FOIA requesters may access “all data produced” by private entities that receive federal research grants – but only when those entities are universities and other nonprofits, not when they are similarly situated for-profit firms. Scholars have suggested that the goal of this amendment, which was championed by the tobacco lobby and the Chamber of Commerce, was to hamstring the EPA by letting critics inspect environmental “scientists’ work down to the smallest detail, giving them myriad new opportunities to discredit studies’ assumptions, methods of analysis, and conclusions, fairly or not.”David Pozen 2017

Freedom of Information Beyond the Freedom of Information Act (Climate)

A lot of cynics say the clean air act was a copout; that it was slapped together by the special interests, the little guy was shut-out, we caved-in to big business lobbyists – all behind closed doors, in some smoke filled room: well, this was the clean air act – we did everything they said we did... But without the smoke... Speaking of “closed doors” I was pretty mad when I tried to get into one of those closed door meetings and found out that the door was locked tight. I pounded and pounded but the door never - opened. I found out later sununu had the locks changed! Hard to believe, because the meeting was in my office!!Muski, Cranston, Cohen & Dole 1990

A Tribute to Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell (Climate)

Most of these meetings occur behind closed doors so lawmakers can escape pressures from lobbyists and reporters, who have made it more difficult for them to handle business “in the sunshine.” This procedure was an integral feature of the 1990 Clean Air Act: virtually none of its major sections resulted from votes on the Senate or the House floor.Richard Cohen 1994 p88

Washington at Work: Back Rooms and Clean Air (Climate)

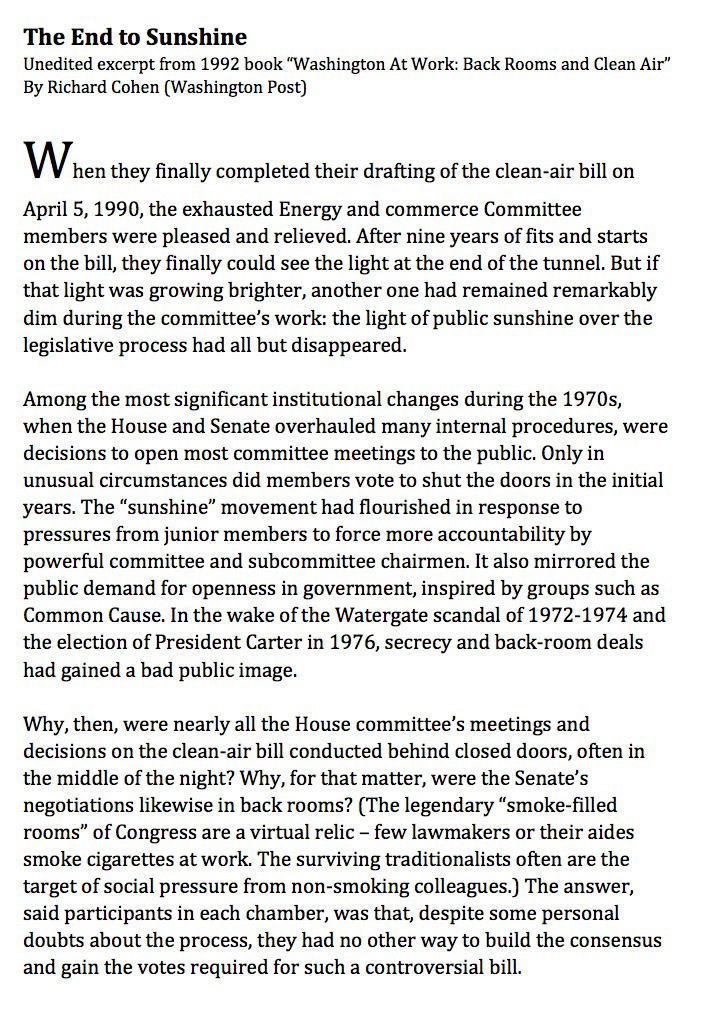

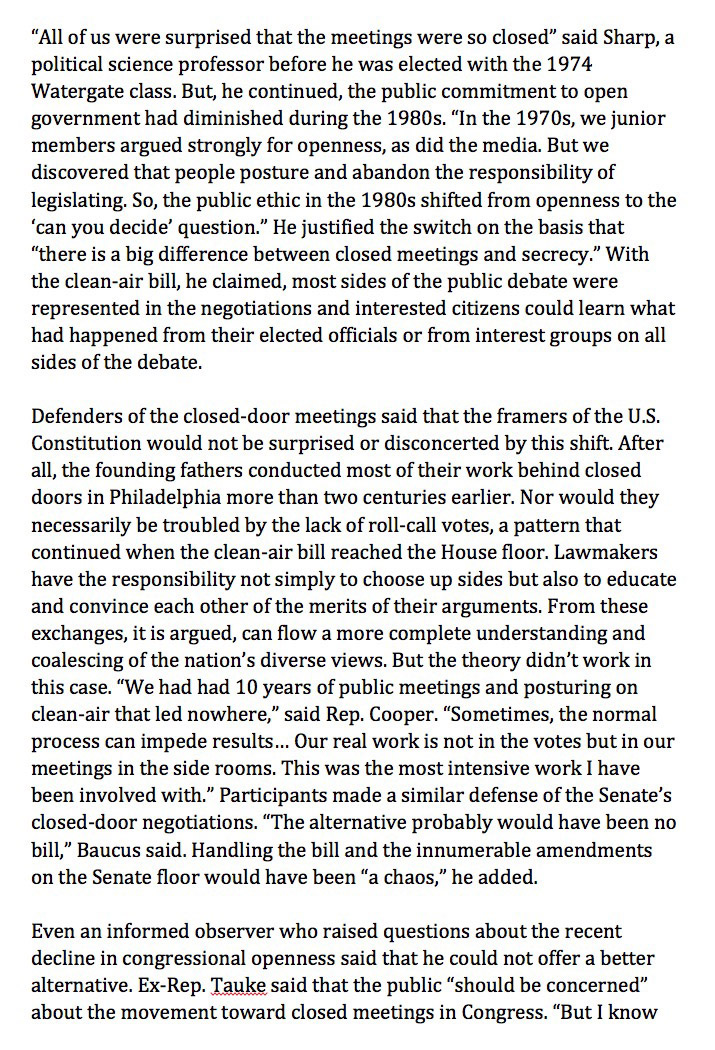

Why, then, were nearly all the House committee’s meetings and decisions on the clean-air bill conducted behind closed doors, often in the middle of the night? Why, for that matter, were the Senate’s negotiations likewise in back rooms? (The legendary “smoke-filled rooms” of Congress are a virtual relic – few lawmakers or their aides smoke cigarettes at work. The surviving traditionalists often are the target of social pressure from non-smoking colleagues.) The answer, said participants in each chamber, was that, despite some personal doubts about the process, they had no other way to build the consensus and gain the votes required for such a controversial bill.Richard Cohen 1994 p88

Washington at Work: Back Rooms and Clean Air (Climate)

An interest group with a specific issue will be very motivated to make its views known and learn what happened. The general public is not so motivated… But behind closed doors, lobbyists don’t know everything that is going on.Republican Thomas Tauke 1992

Washington at Work: Back Rooms and Clean Air (Climate)

The ‘Transparency Turn’ in Global Governance

Transparency has been called ‘an overused but underanalysed concept’. This certainly holds true for contemporary international law. In all major fields of international law – e.g. [climate] environmental law, economic law, human rights law, international humanitarian law, health law, peace-and-security law – demands for more transparent institutions and procedure. have recently been voiced by civil-society actors, by States, and within the international institutions themselves.

Negative Effects of Transparency

Han Morgenthau warned against ‘the vice of publicity’ in diplomatic negotiation : ‘[i]t takes only common sense derived from daily experience to realize that it is impossible to negotiate in public on anything in which parties other than the negotiators are interested.’ In a judgment relating to the Watergate scandal, the US Supreme Court stated: ‘[h]uman experience teaches that those who expect public dissemination of their remarks may well temper candour with a concern for appearances and for their own interests to the detriment of the decision-making process.’

Therefore, in order to mitigate the negative effects of transparency on deliberations, transparency laws and policies will typically contain ‘deliberative exceptions’. For example, in the European Union [EU], access to an institutional document ‘which relates to a matter where the decision has not been taken by the institution, shall be refused if disclosure of the document would seriously undermine the institution’s decision-making process, unless there is an overriding public interest in disclosure.’ Luis Miguel Hinojosa Martinez quotes the World Bank’s justification for secret deliberations: ‘if the view of each ED [Executive Director] is immediately known to the public, it may put undue pressure on EDs, and could also politicize the Bank’s decision-making process’ – and above all for those executive directors who represent several constituencies.

Are deliberation exceptions justified? What exactly are the inhibiting effects of allowing non-participants to listen to deliberations? Sissela Bok has described these as follows: when deliberating before an audience, the deliberants tend to become more inflexible, more radical, and/or they lose candour, becoming averse to risky or innovative opinions. Transparency tempts the participants to rigidity and to posturing, increasing the chances of a stalemate in which no compromise is possible, or alternatively, of a short-circuited and hasty agreement. To pull back from a bargaining position, often done solely for strategic purposes, might be interpreted, if done in full view of the public, as giving in to an opponent. The public gaze tempts deliberators to bypass creative or still tentative idea and leads to premature closure. In sum, the chances for collective learning are diminished.

Concomitantly, the beneficial effect of excluding the public from deliberation is that this allows for fuller consideration of the matter at hand. Deliberators dare to express controversial views behind closed doors, but they also feel as if they have greater freedom to change their minds. They can engage in a tentative process of learning and of assimilating information, considering alternatives and weighing consequences – all of which is needed to arrive at a coherent position. In sum, deliberation behind closed doors can proceed through a process of trial and error, through proposal and counterproposal, through persuasion and bargaining, and sometimes through threat. This is impossible with pressure from the public, including that exerted by special interest groups.

The judicial deliberation and drafting of decision is usually shielded from scrutiny in the sphere of international adjudication, and the rule of various international courts show ‘a considerable degree of uniformity’ in this respect. Neumann and Simma mention a number of reasons why the secrecy of deliberations in international adjudication is even more important than in the domestic realm – notably to prevent government from controlling judges.

In international law-making (treaty negotiation), an aggravating factor of transparency is that the inflexibility and posturing of participants as well as the public pressure of domestic constituencies or special interest groups may frequently lead to a complete breakdown of negotiations so that no desirable outcome results. In fact, these were the reasons given by the representatives of the Great Powers at the opening of the 1919 Paris Peace Conference: ‘[O]pen proceedings would lead to premature public controversy, not only within the interested state, but between the interested nations, render infinitely more difficult the process of give and take, so essential to the negotiations, and hinder the unanimity of agreement which is vital to success’.Anne Peters 2013

Towards Transparency as a Global Norm

Most of these meetings occur behind closed doors so lawmakers can escape pressures from lobbyists and reporters, who have made it more difficult for them to handle business “in the sunshine.” This procedure was an integral feature of the 1990 Clean Air Act: virtually none of its major sections resulted from votes on the Senate or the House floor.Richard Cohen 1994 p88

Washington at Work: Back Rooms and Clean Air (Climate)Note: This citation refers to the successful passage of the 1990 Clean Air Amendments (the most powerful environmental legislation in the past 40 years), which were brokered almost exclusively behind closed doors by Mitchell and others expressly to avoid the pressure of lobbyists. Full citation can be found here.