Citations

James Madison’s writings on the secret ballot predecess the nation’s adoption by over 100 years. In 1785, recollecting his own defeat at the public poll of the liquor-influenced voters of Orange County, Madison urged the secret ballot as “the only radical cure for those arts of Electioneering which poison the very fountain of liberty.”

Here we present citations (with links to original sources) to not just show the benefit of secret ballots, but to support the notion that they are the principle drivers in the diminished partisanship and inequality that were rampant in the late 1800s. To see more info on how congressional voting (made public / not secret) in 1970 have led to our most recent gilded age, click here. Special thanks to Ellery Foutch for unearthing many of these images and her excellent research

Everyone knows that laws which provide a secret ballot have deprived the aristocracy of all its influence.Cicero 50 BC

Everyone knows that laws which provide a secret ballot have deprived the aristocracy of all its influence.Cicero 50 BC

De Legibus

Open voting infests the sea of politics with pirates.George Jacob Holyoake 1868

Open voting infests the sea of politics with pirates.George Jacob Holyoake 1868

A New Defence of the [Secret] Ballot

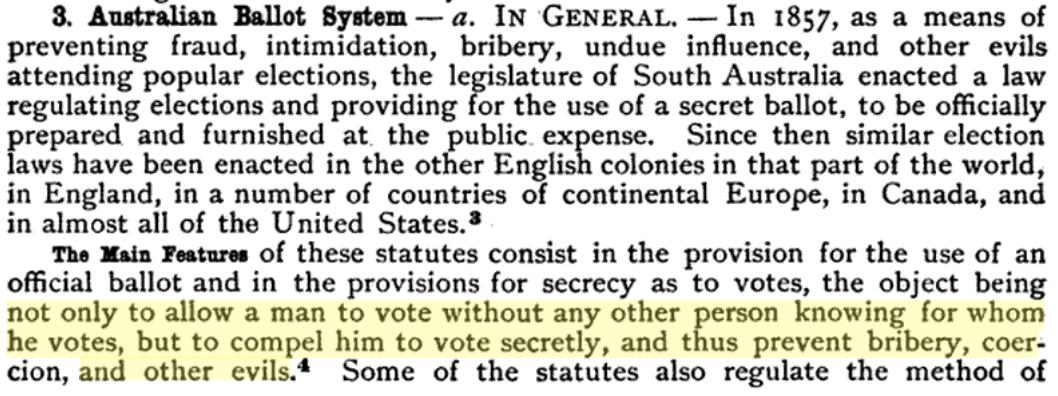

British radical politicians had been calling for the introduction of secret voting at general elections since the 1790s... Most radicals reasoned that secret voting would shift the balance of power in the electoral system from the corrupt aristocracy to the people, by ending voter intimidation and electoral bribery.Martin Spychal 2022

British radical politicians had been calling for the introduction of secret voting at general elections since the 1790s... Most radicals reasoned that secret voting would shift the balance of power in the electoral system from the corrupt aristocracy to the people, by ending voter intimidation and electoral bribery.Martin Spychal 2022

Ballot boxes, bills and unions: Harriet Grote (1792-1878) and the public campaign for the ballot, 1832-9

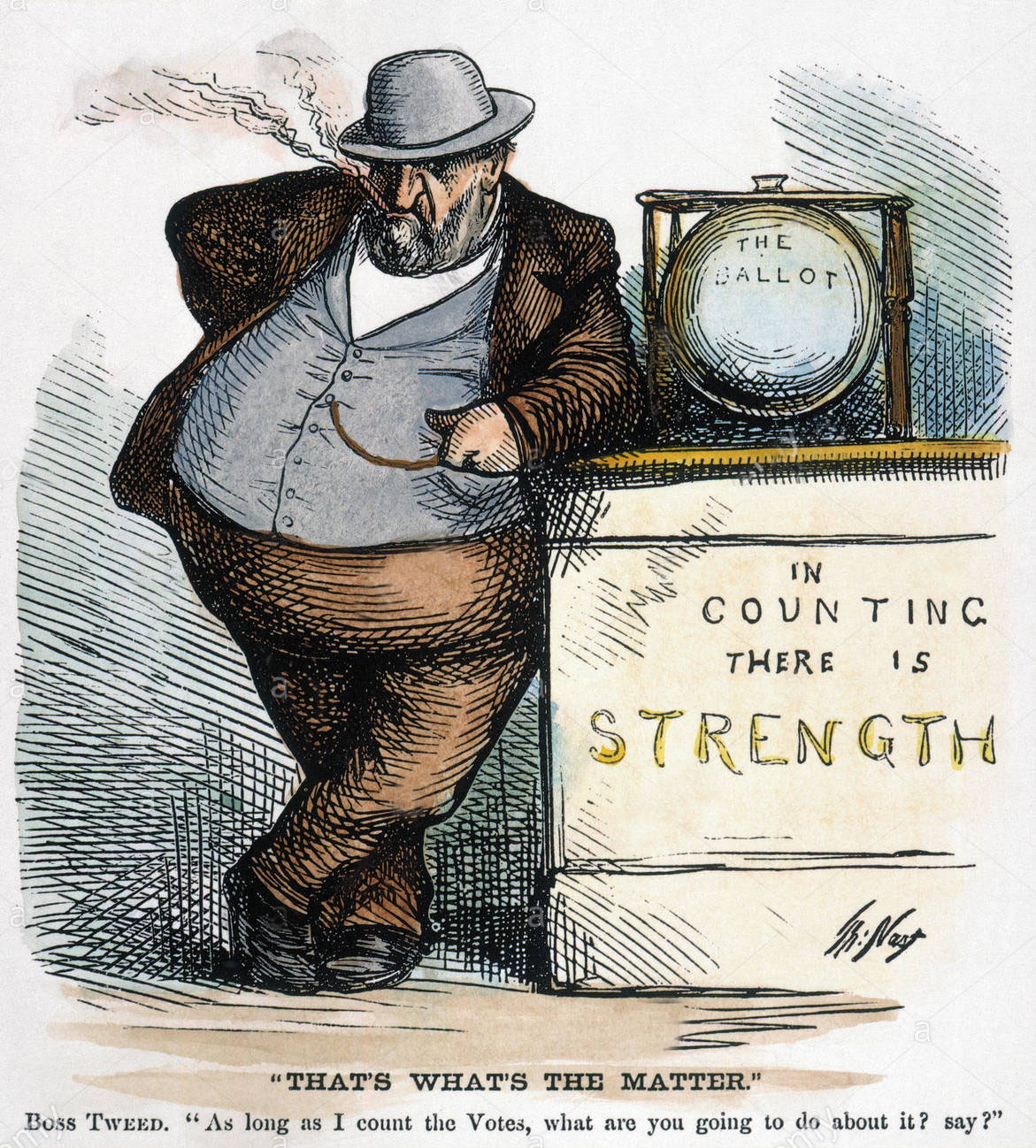

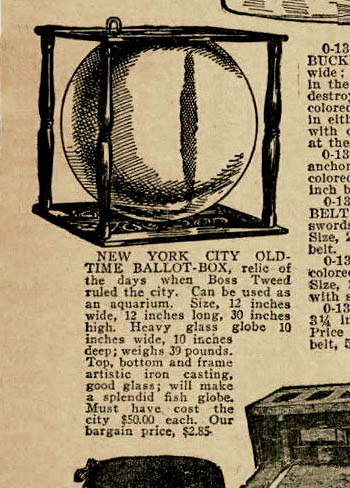

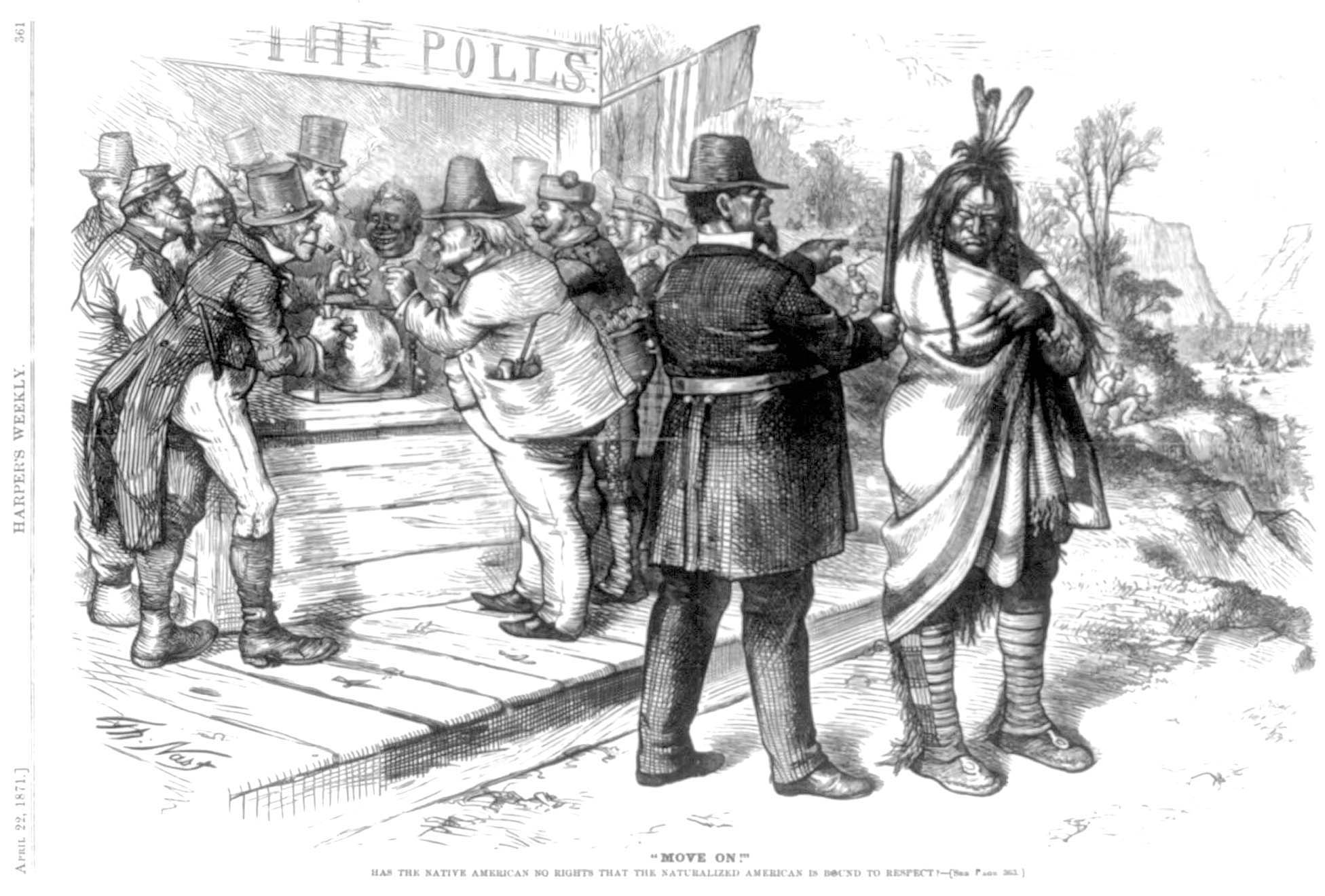

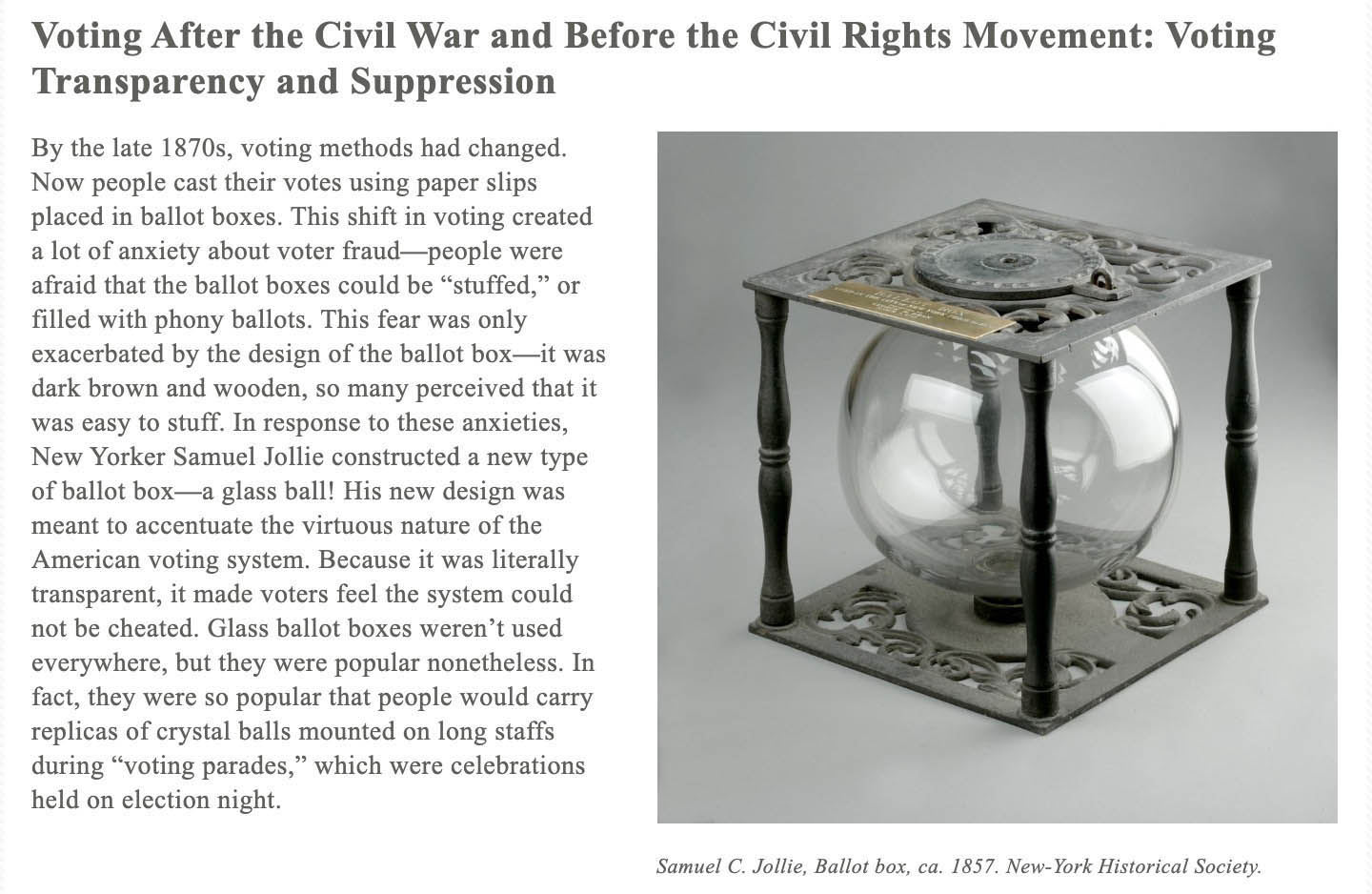

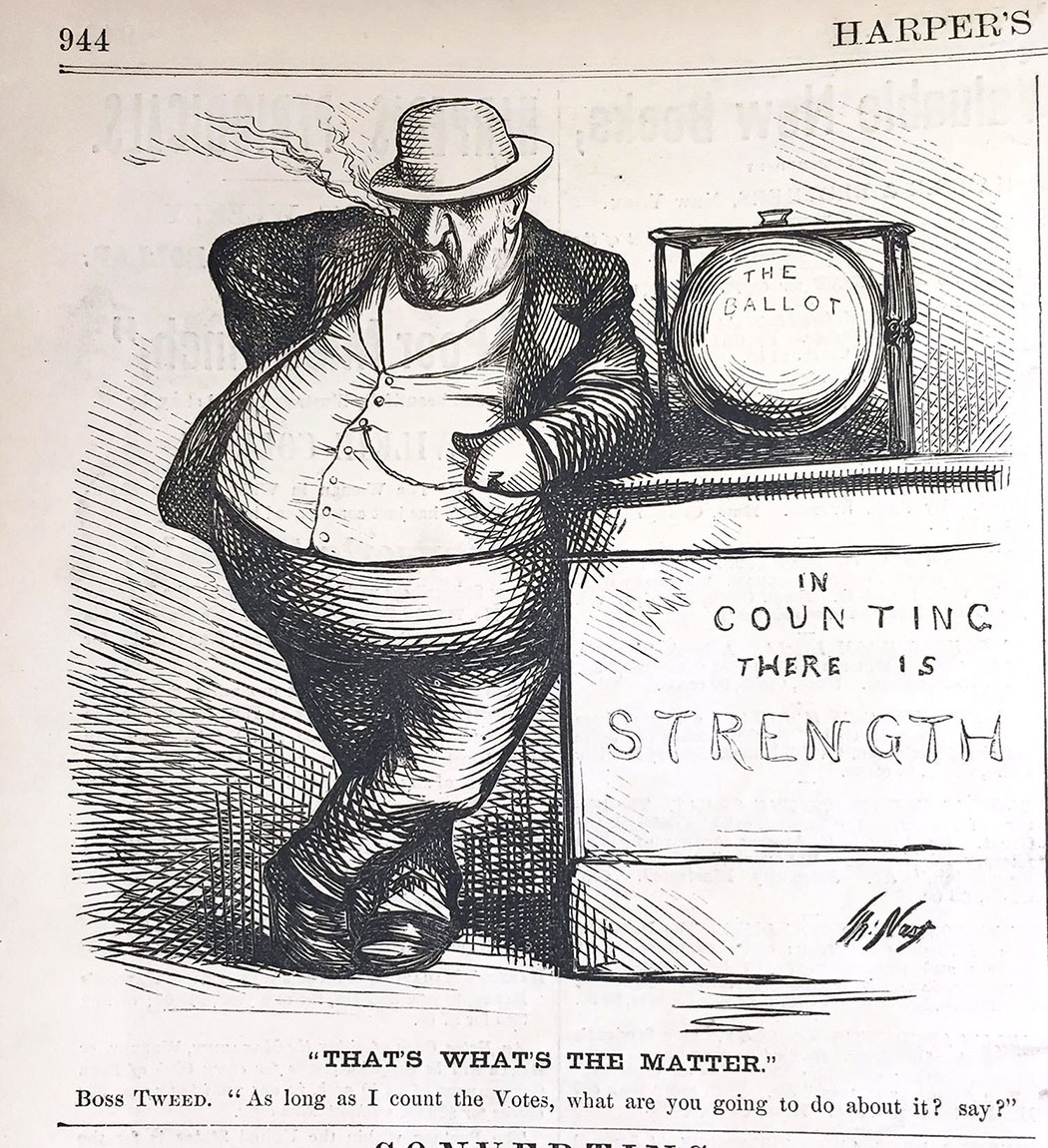

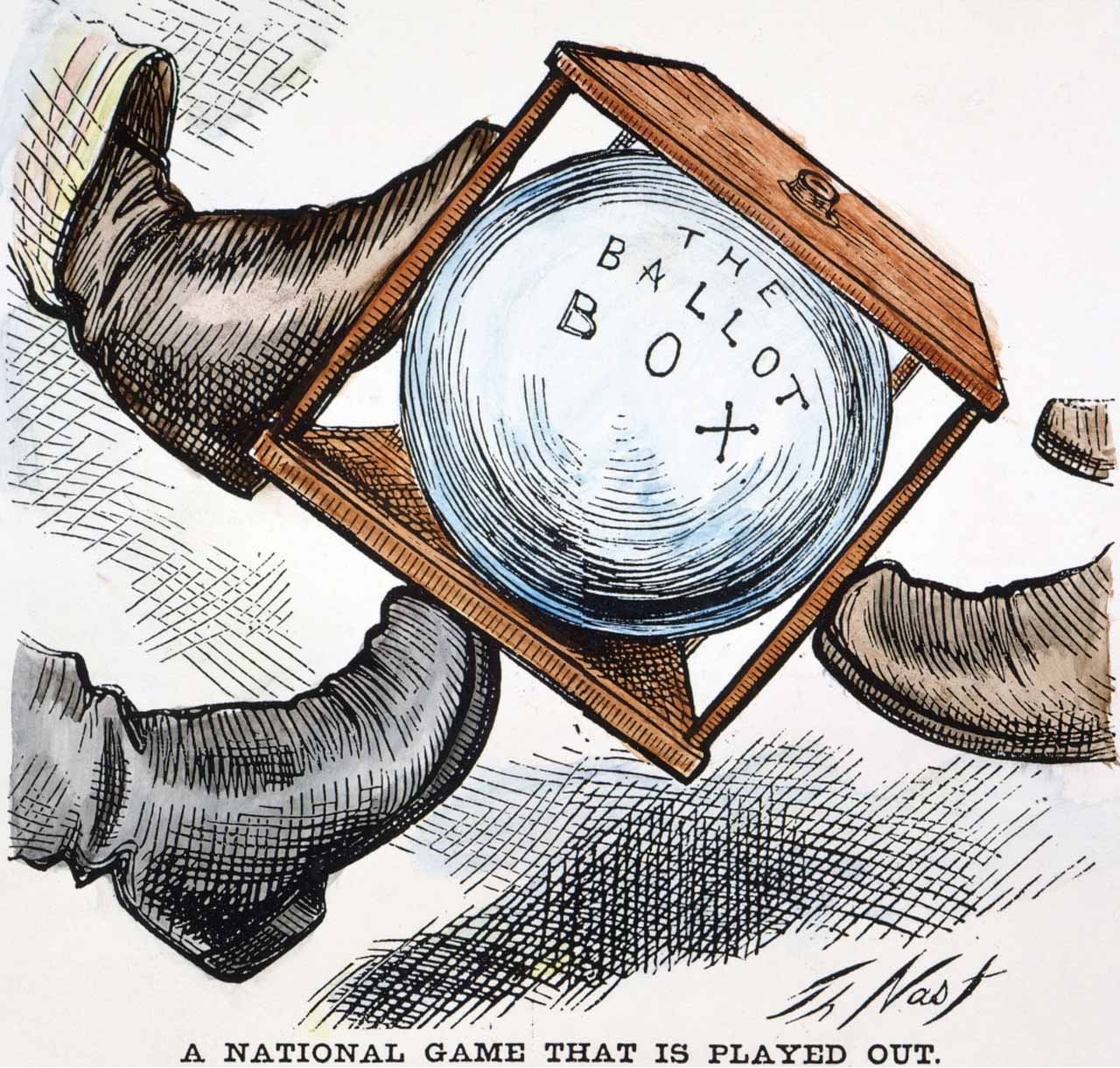

One of the more iconic images of Gilded Age Corruption – Boss Tweed and the Glass (Transparent) Ballot Box 1871

The powerless will always be prevailed upon by the powerful; only secrecy can protect them from bribery and bullying.Jill Lepore 2008

The powerless will always be prevailed upon by the powerful; only secrecy can protect them from bribery and bullying.Jill Lepore 2008

Rock, Paper, Scissors

There can be no doubt that many members of the aristocracy vociferously opposed the introduction of secret voting precisely because they saw in it a dangerous democratic innovation hostile to the influence of property at elections.Bruce Kinzer 2014

There can be no doubt that many members of the aristocracy vociferously opposed the introduction of secret voting precisely because they saw in it a dangerous democratic innovation hostile to the influence of property at elections.Bruce Kinzer 2014

The Un-Englishness of the Secret Ballot

The secret ballot disrupts vote buying because candidates are uncertain how a citizen actually voted.Ian Ayres 1999

The secret ballot disrupts vote buying because candidates are uncertain how a citizen actually voted.Ian Ayres 1999

Disclosure vs. Anonymity in Campaign Finance

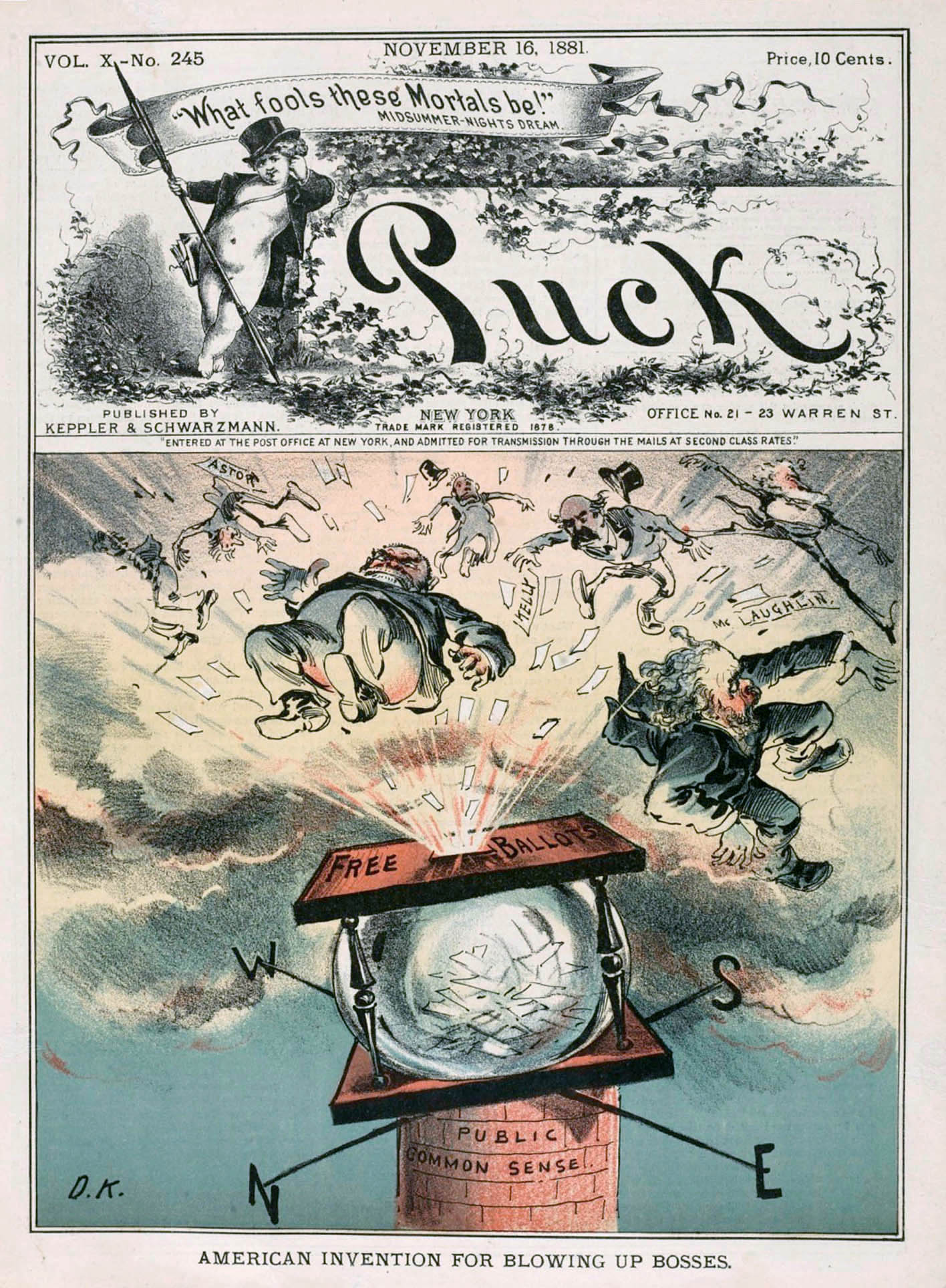

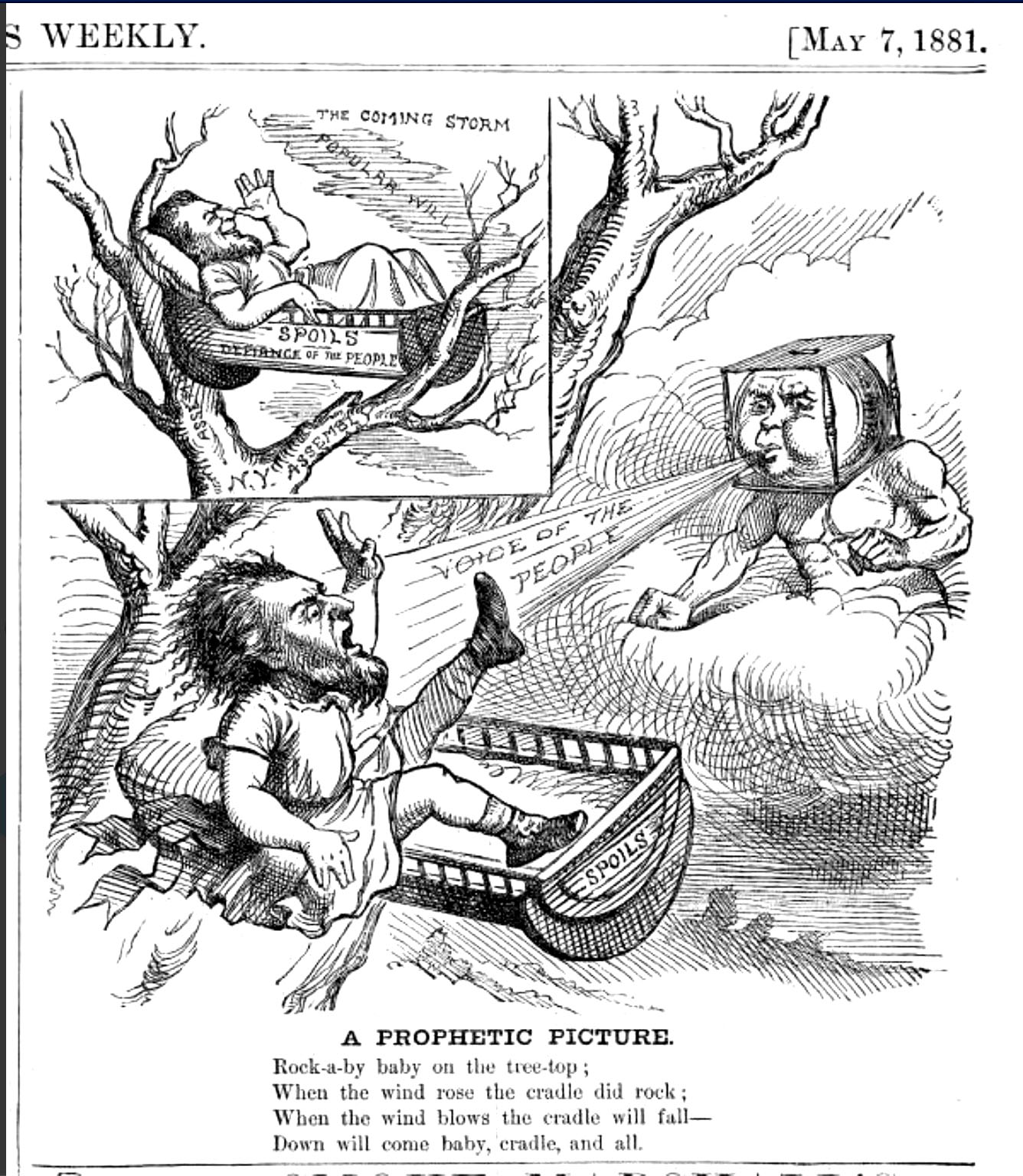

“American Invention for Blowing Up Bosses” - Puck 1881

Depicts ballot box labeled "Free Ballots" exploding atop a brick tower labeled "Public Common Sense", blasting John Kelly, Hugh McLaughlin, Roscoe Conkling, and William W. Astor into the sky.

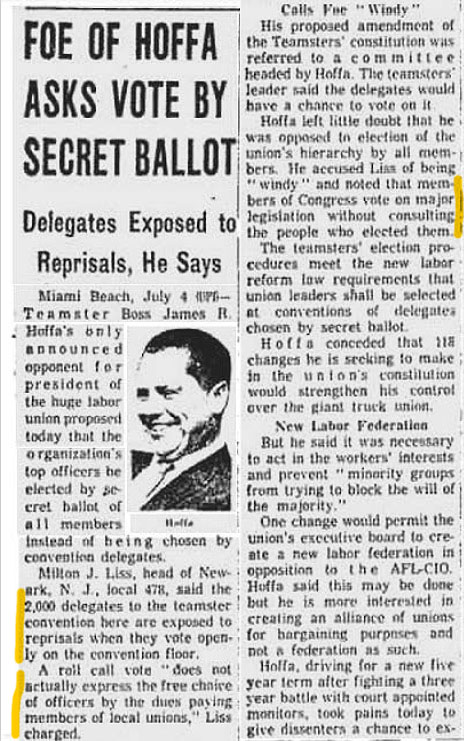

If they want to vote themselves, they won’t get no money from me.Darrel Fugate 1987

If they want to vote themselves, they won’t get no money from me.Darrel Fugate 1987

A Vote-buyer on his Trade - to Win you have to do it

The failure of the law to secure secrecy, opened the door to bribery, intimidation, and corruption. It is hard, however, to imagine a system more open to corruption than the one just described.Eldon Cobb Evans 1917

The failure of the law to secure secrecy, opened the door to bribery, intimidation, and corruption. It is hard, however, to imagine a system more open to corruption than the one just described.Eldon Cobb Evans 1917

A History of the Australian Ballot System in the United States

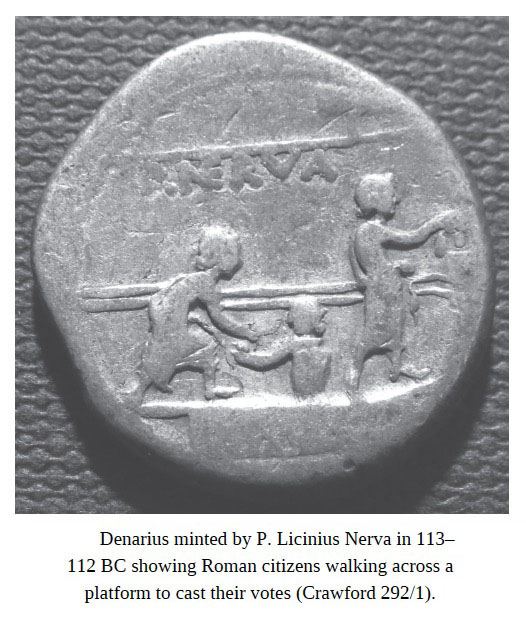

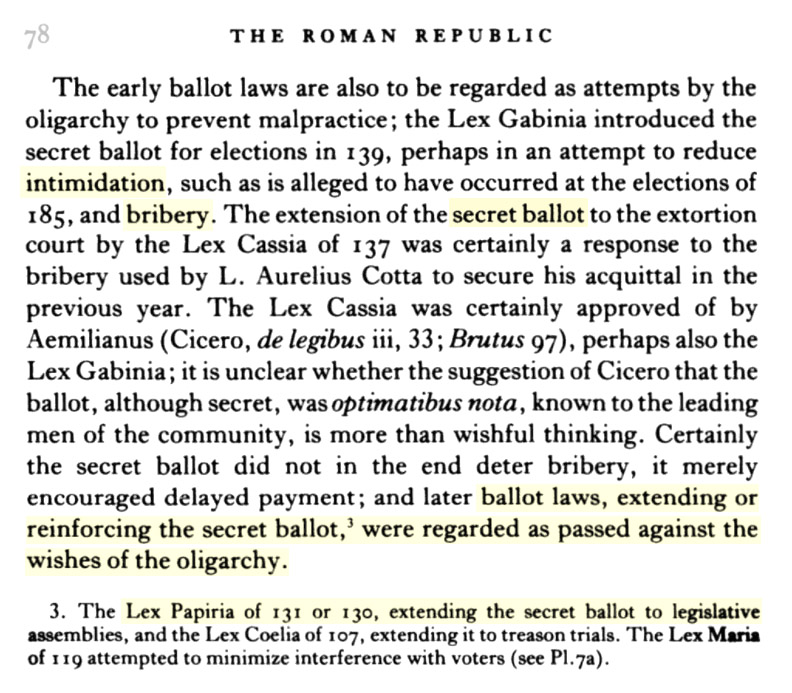

A series of ballot laws, passed in the second part of the second century, made the voting secret in all the Roman assemblies. The ancient sources which refer to the introduction of the ballot are few; they describe it as a radical innovation. Modern scholars have long regarded the change as a democratic one, lessening the control of the upper classes over the electorate, and enhancing the voters’ effective freedom of choice.Alexander Yakobson 1995

A series of ballot laws, passed in the second part of the second century, made the voting secret in all the Roman assemblies. The ancient sources which refer to the introduction of the ballot are few; they describe it as a radical innovation. Modern scholars have long regarded the change as a democratic one, lessening the control of the upper classes over the electorate, and enhancing the voters’ effective freedom of choice.Alexander Yakobson 1995

The Secret Ballot and its Effects in the Late Roman Republic

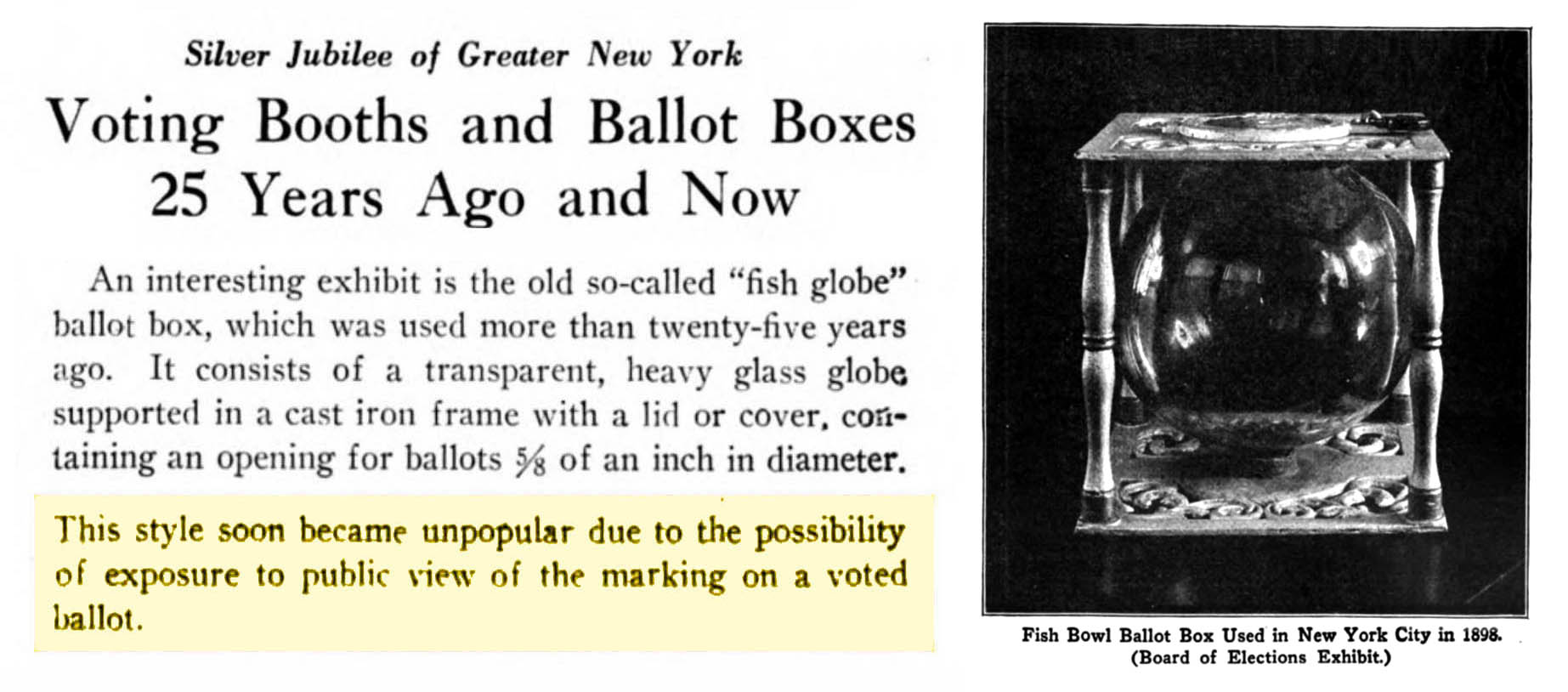

1923 article describing how the transparency of glass ballot box became obsolete when they realized it aided in corruption

Victorian elections in England and Wales were far, far more violent than has previously been thought. During the last general election before the secret ballot in 1868...seventeen deaths were directly caused by the contests taking place.Gary Hutchison 2022

Victorian elections in England and Wales were far, far more violent than has previously been thought. During the last general election before the secret ballot in 1868...seventeen deaths were directly caused by the contests taking place.Gary Hutchison 2022

The Secret Ballot: The Secret to Reducing Electoral Violence?

In 1882 a Conservative M.P. complained that “the Ballot Act [the introduction of the secret ballot] had promoted that most un-English practice of taking bribes from both sides, or voting against the side from which a bribe had been accepted.”Alexander Yakobson 1995

In 1882 a Conservative M.P. complained that “the Ballot Act [the introduction of the secret ballot] had promoted that most un-English practice of taking bribes from both sides, or voting against the side from which a bribe had been accepted.”Alexander Yakobson 1995

The Secret Ballot and its Effects in the Late Roman Republic

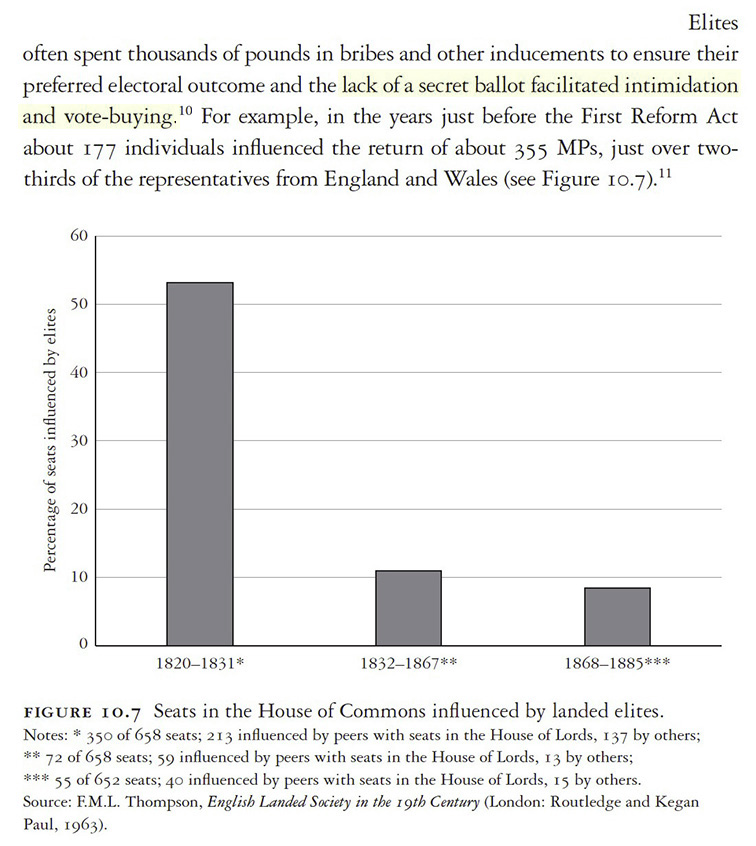

The Ballot Act of 1872 finally gave Britain the secret ballot, thereby striking a major blow against electoral corruption and intimidation and greatly diminishing the ability of the landowning elite to control electoral outcomes.Sheri Berman 2019

The Ballot Act of 1872 finally gave Britain the secret ballot, thereby striking a major blow against electoral corruption and intimidation and greatly diminishing the ability of the landowning elite to control electoral outcomes.Sheri Berman 2019

Democracy and Dictatorship in Europe

Patrick Kuhn 2021 - Secret Ballot Does Not Eliminate but Changes the Type and Timing of Election Violence

Without the [secret] Australian ballot, George wrote, “we might almost think soberly of the propriety of putting up our offices at auction.”Henry George 1871

Without the [secret] Australian ballot, George wrote, “we might almost think soberly of the propriety of putting up our offices at auction.”Henry George 1871

Bribery in Elections

In a debate in the German parliament [before the introduction of the secret ballot], Heinrich Rickert described how employers would “lead the voters to the voting place like animals to slaughter. In front of the door of the voting precinct some supervisor or inspector pushes a ballot in the hands of the worker. As [the worker] does not want to lose his job, he is in no position to vote according to his conviction.”Isabela Mares 2015

In a debate in the German parliament [before the introduction of the secret ballot], Heinrich Rickert described how employers would “lead the voters to the voting place like animals to slaughter. In front of the door of the voting precinct some supervisor or inspector pushes a ballot in the hands of the worker. As [the worker] does not want to lose his job, he is in no position to vote according to his conviction.”Isabela Mares 2015

From Open Secrets to Secret Voting

Over the next year the Morrisites, billing themselves as “the party of the people,” widened their popular appeal by calling for... the adoption of the secret ballot (which would allow ordinary people to vote “for the Man they Love, and not for the haughty Tyrant they fear, and consequently hate”).Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace 1998

Over the next year the Morrisites, billing themselves as “the party of the people,” widened their popular appeal by calling for... the adoption of the secret ballot (which would allow ordinary people to vote “for the Man they Love, and not for the haughty Tyrant they fear, and consequently hate”).Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace 1998

Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898

They handed over to workers who were dependent on them ballots that were folded in different ways. Some were folded in the shape of a triangle, others in the shape of a diamond, a hat, or an accordion. Naturally, they did not hesitate to inform these voters that they would keep an eye on them when the votes were counted and that it was imperative to find these particular ballots. Journal Officiel de la Republique Française 1914

They handed over to workers who were dependent on them ballots that were folded in different ways. Some were folded in the shape of a triangle, others in the shape of a diamond, a hat, or an accordion. Naturally, they did not hesitate to inform these voters that they would keep an eye on them when the votes were counted and that it was imperative to find these particular ballots. Journal Officiel de la Republique Française 1914

Débats Chambre

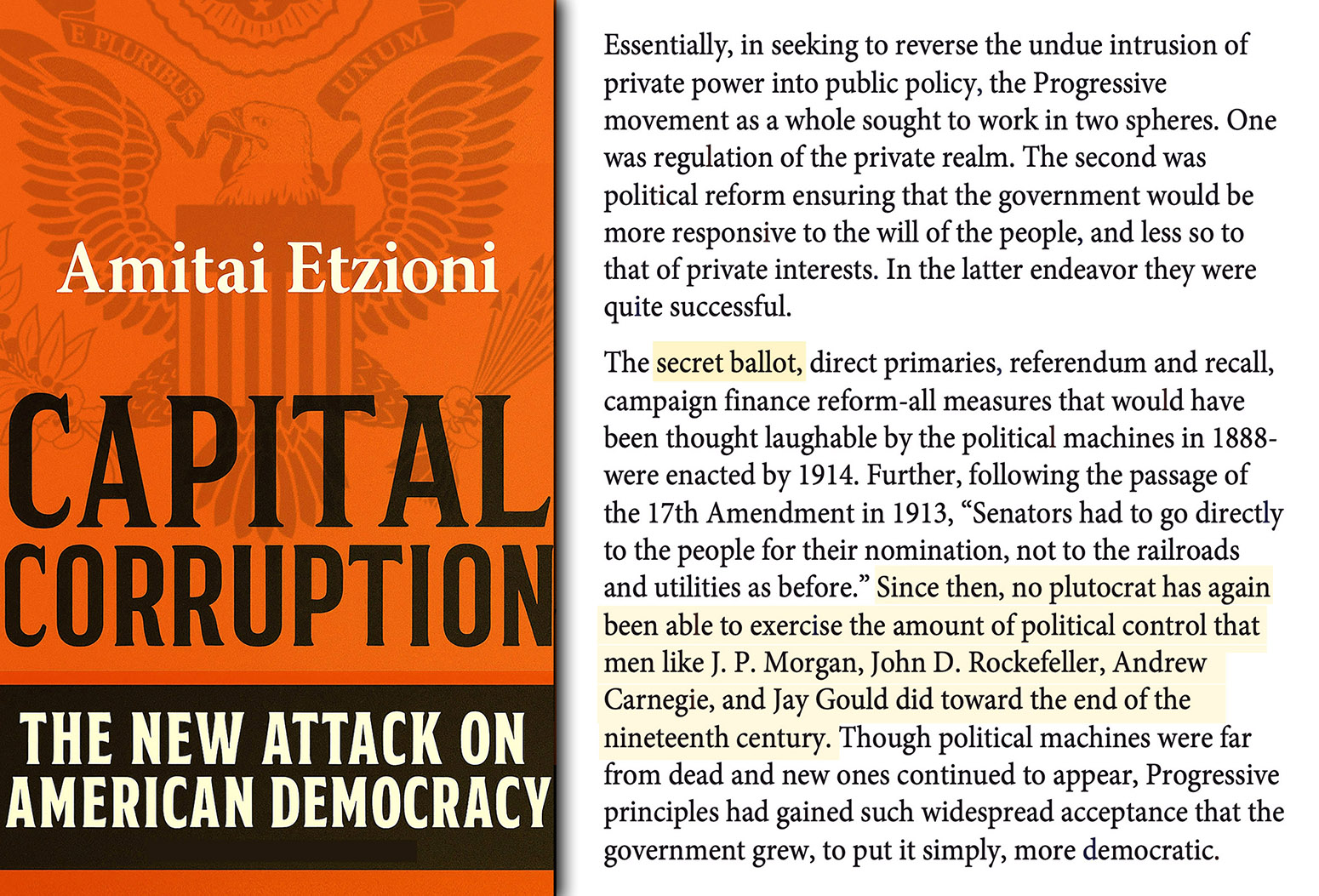

Amitai Etzioni 1988 - Capital Corruption

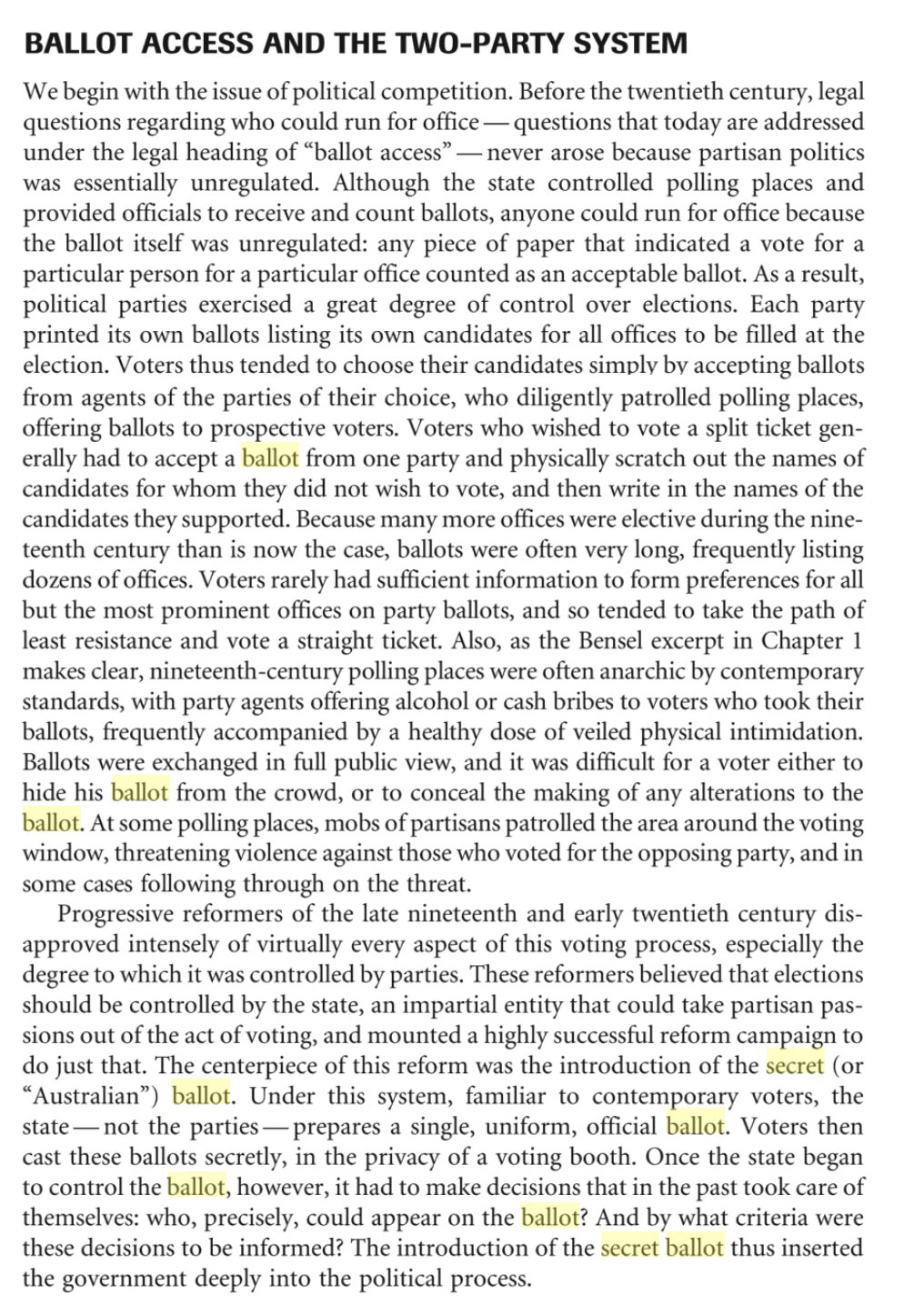

Essentially, in seeking to reverse the undue intrusion of private power into public policy, the Progressive movement as a whole sought to work in two spheres. One was regulation of the private realm. The second was political reform ensuring that the government would be more responsive to the will of the people, and less so to that of private interests. In the latter endeavor they were quite successful. The secret ballot, direct primaries, referendum and recall, campaign finance reform-all measures that would have been thought laughable by the political machines in 1888-were enacted by 1914. Further, following the passage of the 17th Amendment in 1913, “Senators had to go directly to the people for their nomination, not to the railroads and utilities as before.” Since then, no plutocrat has again been able to exercise the amount of political control that men like J. P. Morgan, John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, and Jay Gould did toward the end of the nineteenth century. Though political machines were far from dead and new ones continued to appear, Progressive principles had gained such widespread acceptance that the government grew, to put it simply, more democratic.

Because most democracies use a secret ballot, citizens can accept the money but vote for whichever candidate they prefer even if their preferred candidate did not offer similar gifts.Ari Pradhanawati, George Towar Ikbal Tawakkal & Andrew D. Garner 2018

Because most democracies use a secret ballot, citizens can accept the money but vote for whichever candidate they prefer even if their preferred candidate did not offer similar gifts.Ari Pradhanawati, George Towar Ikbal Tawakkal & Andrew D. Garner 2018

Age of Voting their Conscience

Moreover, “the individuals in each group announced their choice orally, one by one, to the teller, or rogator. How individuals voted was therefore a very public affair”; the combination of voting procedures and social realities ensured the upper classes a powerful influence over the voting assemblies.Alexander Yakobson 1995

Moreover, “the individuals in each group announced their choice orally, one by one, to the teller, or rogator. How individuals voted was therefore a very public affair”; the combination of voting procedures and social realities ensured the upper classes a powerful influence over the voting assemblies.Alexander Yakobson 1995

The Secret Ballot and its Effects in the Late Roman Republic

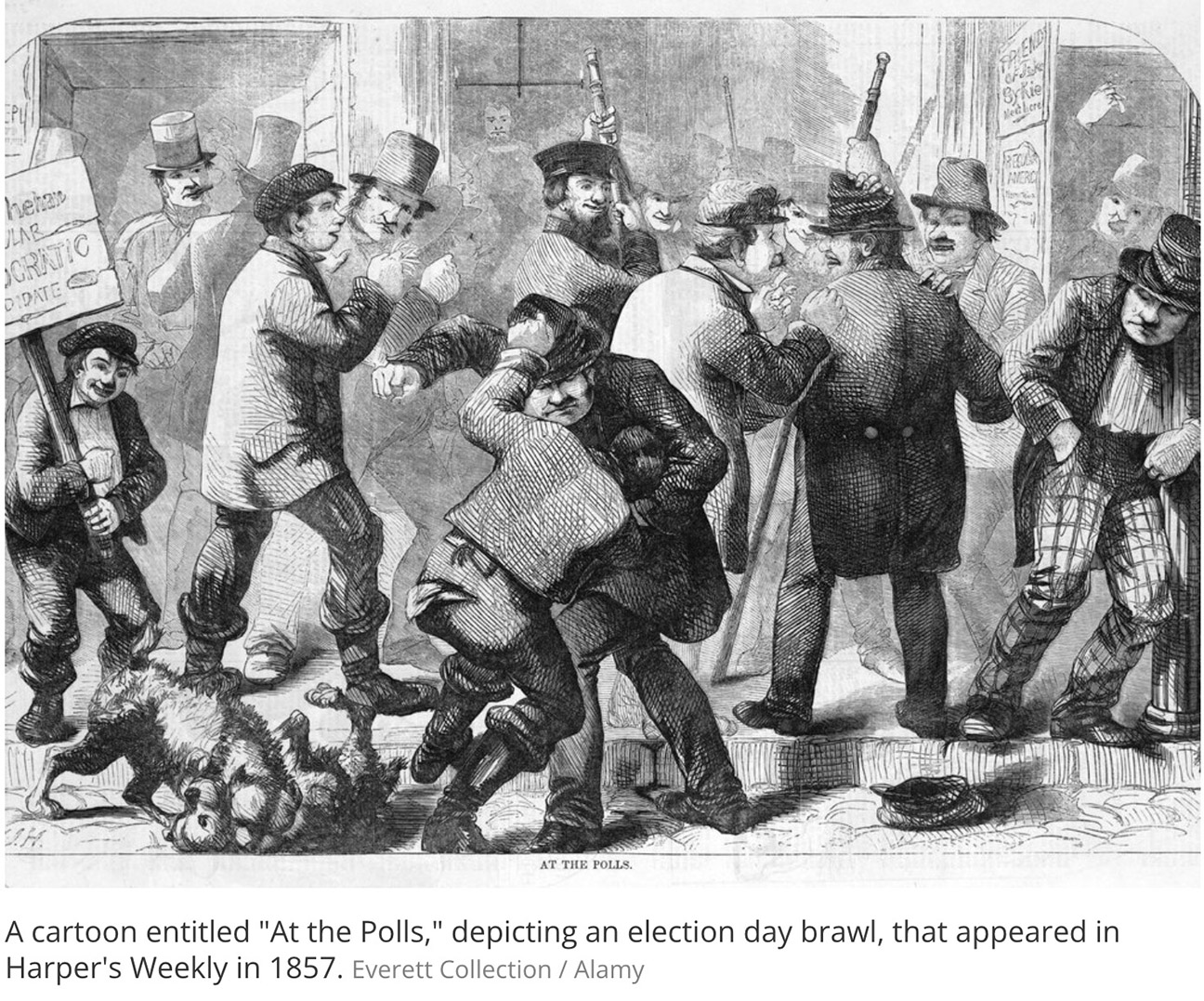

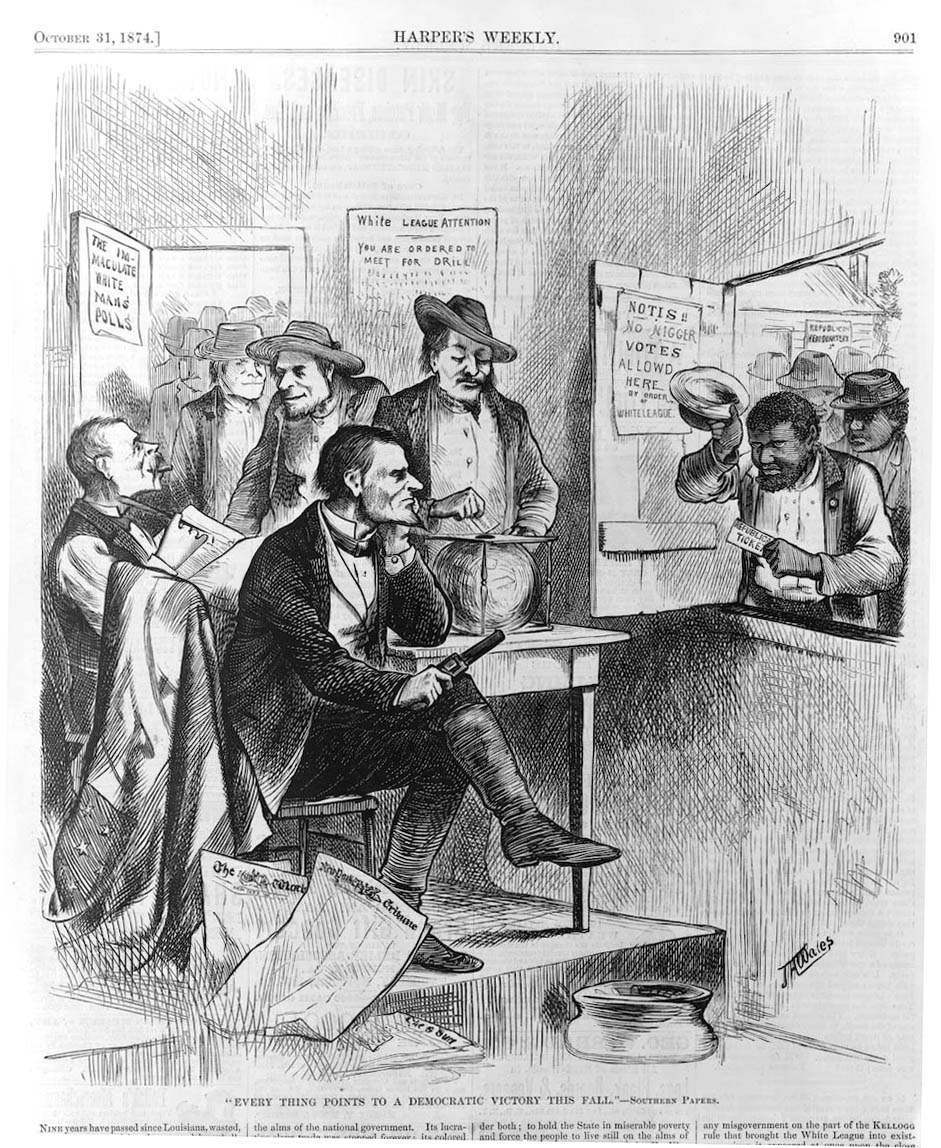

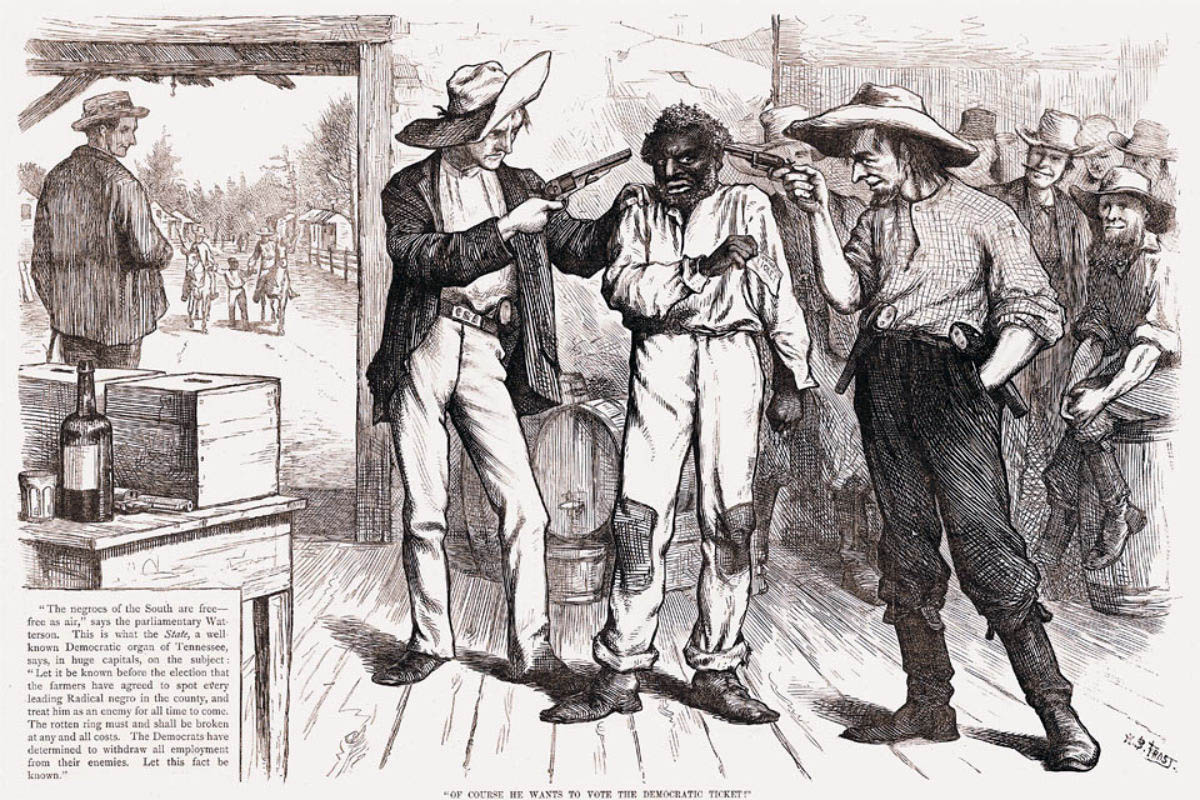

“Scarcely an election goes by without somebody being killed.”U.S. Marshall 1881

“Scarcely an election goes by without somebody being killed.”U.S. Marshall 1881

New Perspectives on Election Fraud in the Gilded Age

American clientelism (of the late 1800s) was dealt a blow by ballot reform.Susan Stokes & Thad Dunning 2010

American clientelism (of the late 1800s) was dealt a blow by ballot reform.Susan Stokes & Thad Dunning 2010

What Killed Vote Buying?

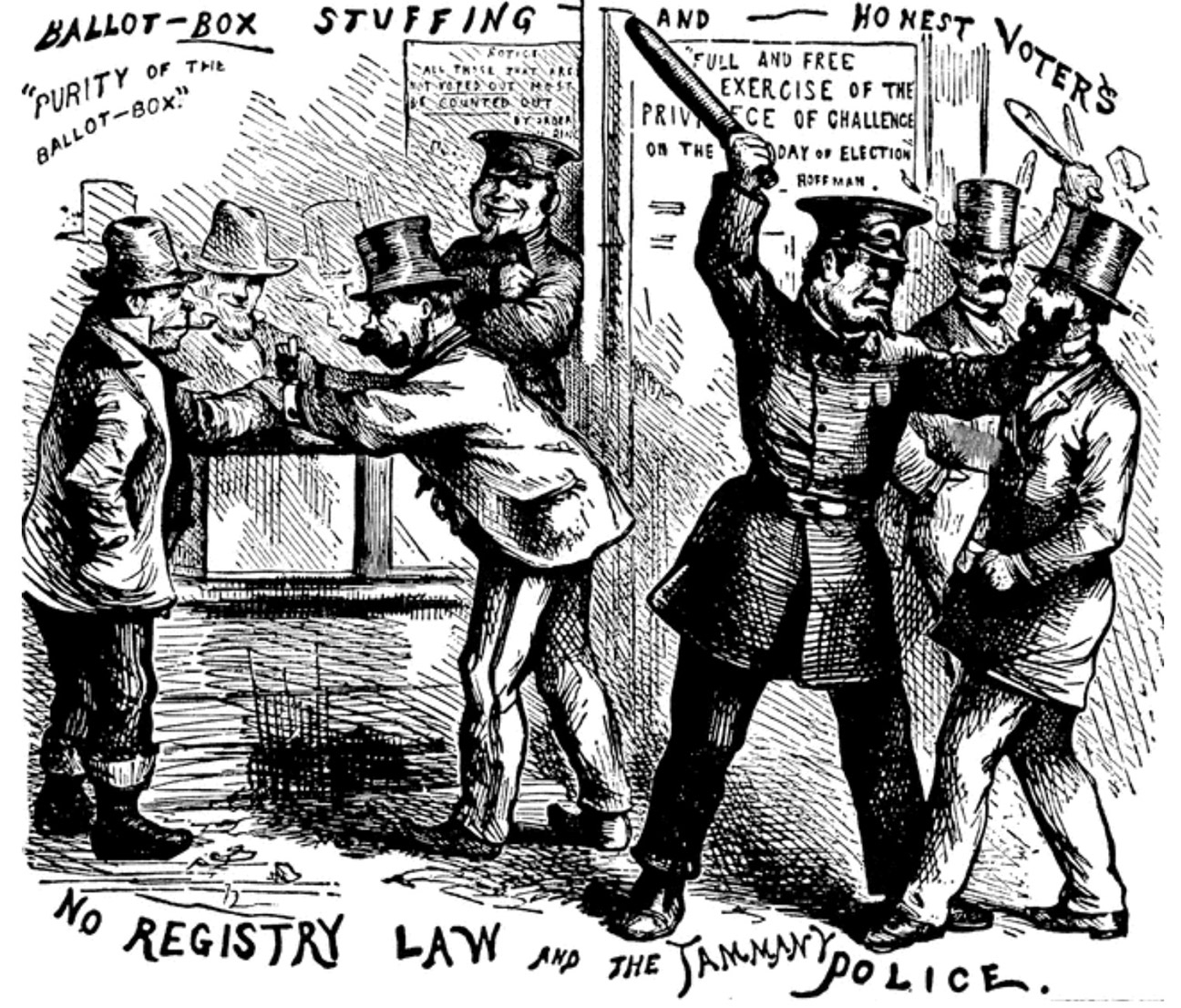

1857 Political Cartoon "At the Polls" depicting an election day brawl

The Romans also used the secret ballot to limit the influence of the rich.Jon Elster 2013

The Romans also used the secret ballot to limit the influence of the rich.Jon Elster 2013

Securities Against Misrule

In Rome “the peoples voices were bought and sold, and that by the poore, and thence it came that the richest man... made himself a perpetuall dictator.”Colonel Rich 1647

In Rome “the peoples voices were bought and sold, and that by the poore, and thence it came that the richest man... made himself a perpetuall dictator.”Colonel Rich 1647

The Putney Debates, London: The Historical Society

The vote is fundamental to democratic government, because the individuals who make up the demos rule only when they can register their decisions effectively. Sometimes, if order is to be maintained and the people are to escape reprisals for having expressed their best judgment, the vote must be secret. Lysias and his hearers understood the danger of immediate, desperate reprisals that can follow open voting. He recalls, in his speech against Agoratos, how the Thirty, by forcing citizens to vote openly, secured the verdicts they wanted (Lysias, XIII, 37; cf. Thucydides, IV, 74). But there are other reprisals. Disapproval by friends, the loss of a favor that was hoped for, fear of these too influenced a man’s vote, and it is against these influences and more that the secret ballot protects the voter (see also Xenophon, Symnp., V,8; Demosthenes, XIX,239). Voting is a radical idea, and especially secret voting.Alan L. Boegehold 1963

The vote is fundamental to democratic government, because the individuals who make up the demos rule only when they can register their decisions effectively. Sometimes, if order is to be maintained and the people are to escape reprisals for having expressed their best judgment, the vote must be secret. Lysias and his hearers understood the danger of immediate, desperate reprisals that can follow open voting. He recalls, in his speech against Agoratos, how the Thirty, by forcing citizens to vote openly, secured the verdicts they wanted (Lysias, XIII, 37; cf. Thucydides, IV, 74). But there are other reprisals. Disapproval by friends, the loss of a favor that was hoped for, fear of these too influenced a man’s vote, and it is against these influences and more that the secret ballot protects the voter (see also Xenophon, Symnp., V,8; Demosthenes, XIX,239). Voting is a radical idea, and especially secret voting.Alan L. Boegehold 1963

Toward a Study of Athenian Voting Procedure

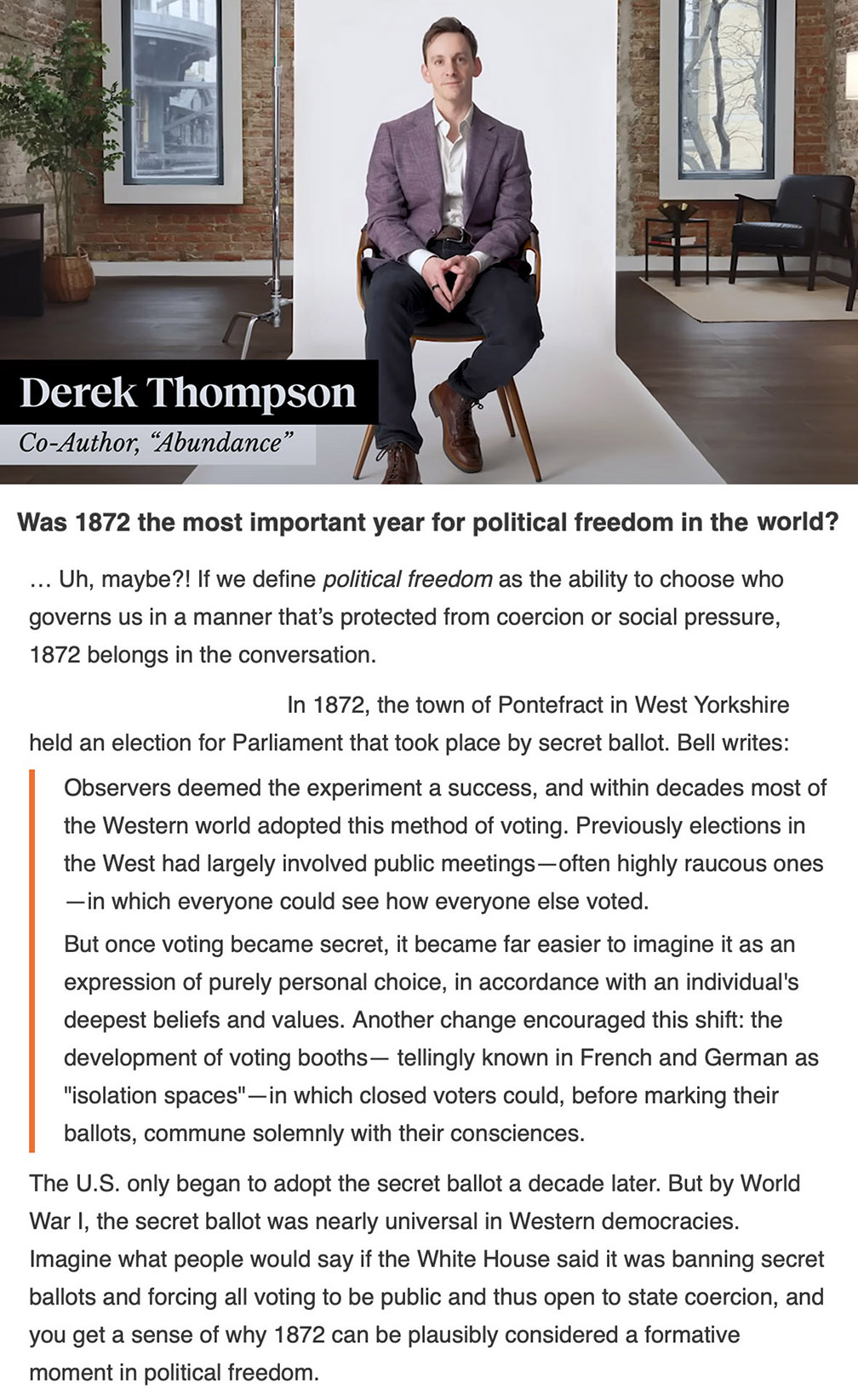

Derek Thompson 2025 - Was 1872 the most important year for political freedom in the world?

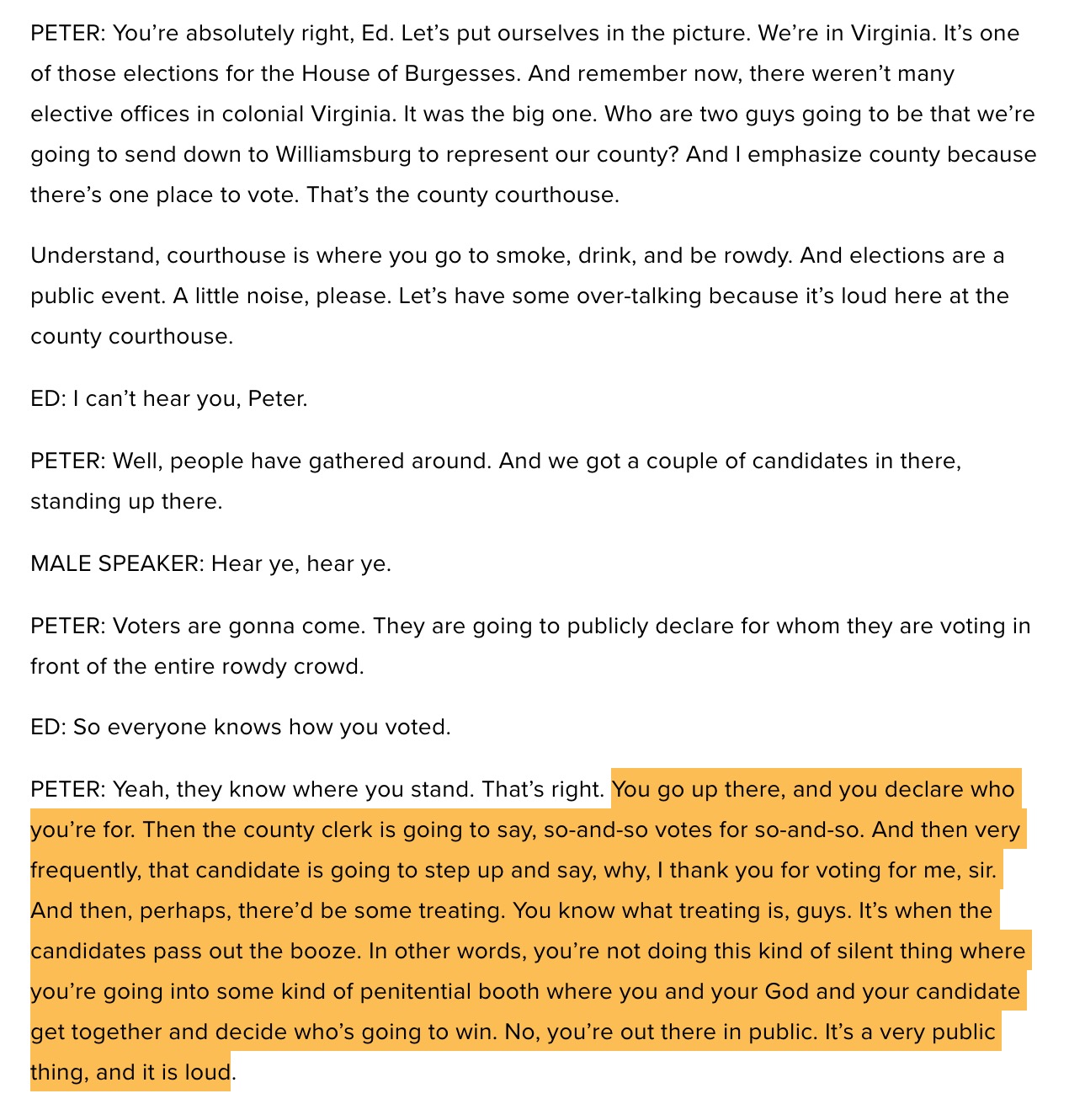

In the essay "My Freedom, My Choice” about the book The Age of Choice by Sophia Rosenfield, author David A. Bell points out that for most of democracy’s history, voting was a performative and communal act, with public declarations and even open parades. The secret ballot that most Americans associate with the ballot box is a relatively recent invention, at least in modern Western history. In 1872, the town of Pontefract in West Yorkshire held an election for Parliament that took place by secret ballot. Bell writes: >> “Observers deemed the experiment a success, and within decades most of the Western world adopted this method of voting. Previously elections in the West had largely involved public meetings—often highly raucous ones—in which everyone could see how everyone else voted. Such settings made it difficult to conceive of the act as anything other than an expression of communal as opposed to individual preference. But once voting became secret, it became far easier to imagine it as an expression of purely personal choice, in accordance with an individual's deepest beliefs and values. Another change encouraged this shift: the development of voting booths— tellingly known in French and German as "isolation spaces" << —in which closed voters could, before marking their ballots, commune solemnly with their consciences.” The U.S. only began to adopt the secret ballot a decade later. But by World War I, the secret ballot was nearly universal in Western democracies. Imagine what people would say if the White House said it was banning secret ballots and forcing all voting to be public and thus open to state coercion, and you get a sense of why 1872 can be plausibly considered a formative moment in political freedom.

Restrictions on speech around polling places on election day are as venerable a part of the American tradition as the secret ballot.Justice Anton Scalia 1992

Restrictions on speech around polling places on election day are as venerable a part of the American tradition as the secret ballot.Justice Anton Scalia 1992

From Clamor to Calm: Restrictions on Speech at Polling Places

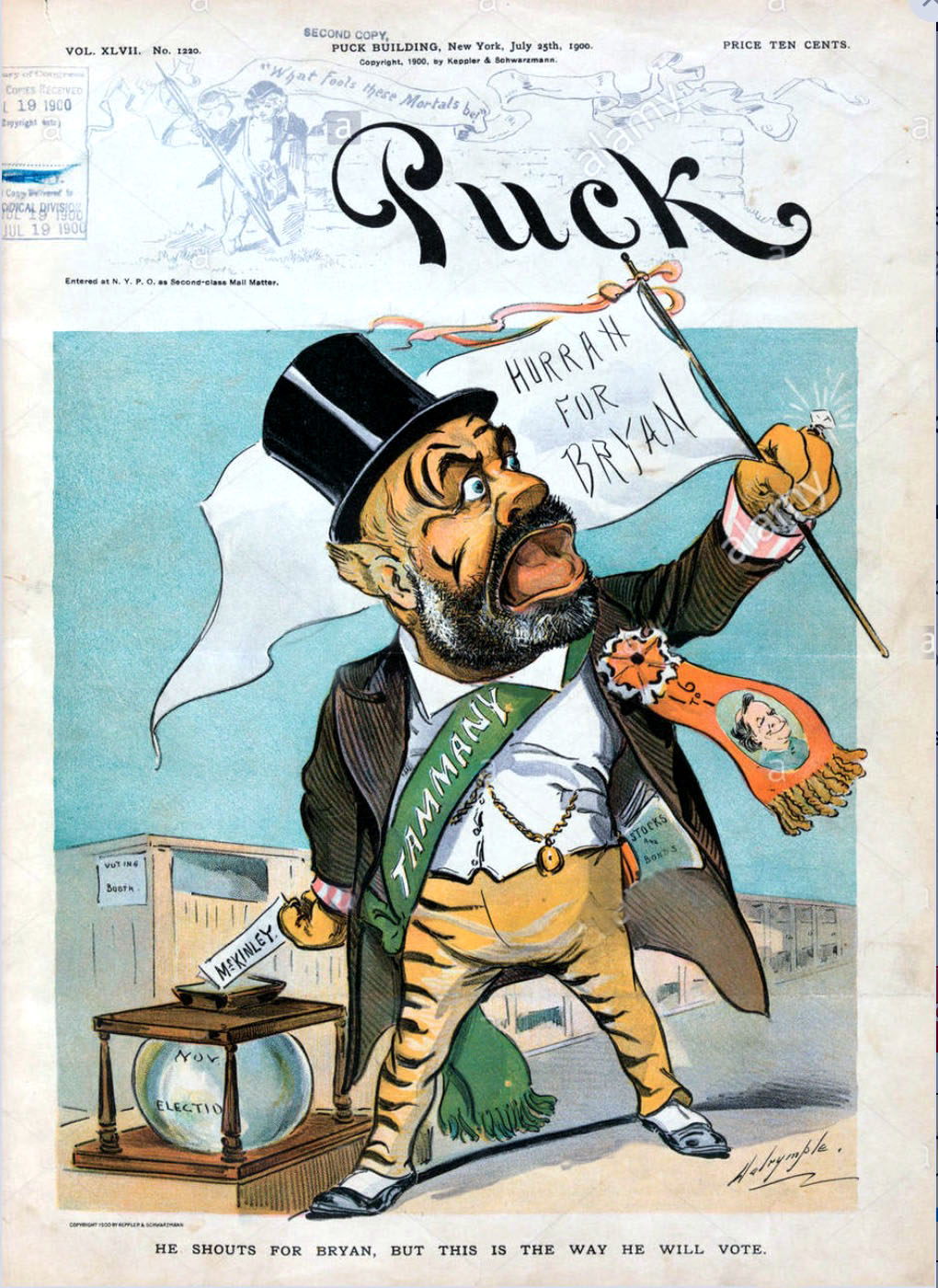

By fighting for the secret ballot… it would be the only way, he warned, to “check the arrogance of corrupt partisan organization.”Puck Magazine 1884

By fighting for the secret ballot… it would be the only way, he warned, to “check the arrogance of corrupt partisan organization.”Puck Magazine 1884

Holding the Tiger - The Gilded Age

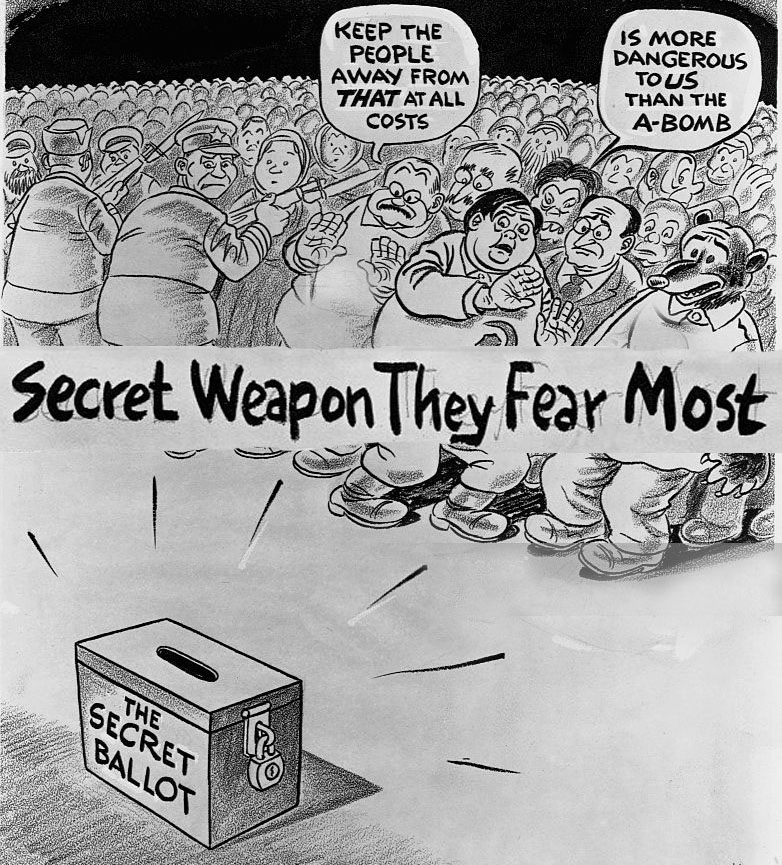

Voter intimidation has cropped up in places across the nation, but the voting booth remains the one place where nobody can get to you.Lily Hay Newman 2022

Voter intimidation has cropped up in places across the nation, but the voting booth remains the one place where nobody can get to you.Lily Hay Newman 2022

Secret Ballot Is US Democracy’s Last Line of Defense

Newman 2022 - Secret Ballot Is US Democracy’s Last Line of Defense

In Tiberius’s conception [Roman emperor ad 14–37], the assembly would become the dominant force directing all facets of Roman policy. Led by assertive tribunes and protected by secret ballots that enabled plebeians to vote anonymously for the first time, the assembly could legislate as the popular will demanded.Edward J. Watts 2018

In Tiberius’s conception [Roman emperor ad 14–37], the assembly would become the dominant force directing all facets of Roman policy. Led by assertive tribunes and protected by secret ballots that enabled plebeians to vote anonymously for the first time, the assembly could legislate as the popular will demanded.Edward J. Watts 2018

Mortal Republic - How Rome Fell Into Tyranny

Of the attempts to prevent corrupt influence in the first place, the most notable in the period under discussion was the substitution of secret for open voting.Charles Seymour 1915

Of the attempts to prevent corrupt influence in the first place, the most notable in the period under discussion was the substitution of secret for open voting.Charles Seymour 1915

Electoral Reform - The Final Attack Upon Corruption

My attention was called to the peculiar way they had of managing the voters there, I stepped up to the little railing that they had there to go around and up to the polls and I saw two men stationed at the entrance where the voters went it. One was a Mr. Chase, and the other was a Mr. Knox. I saw that the help of the village [employees/thugs of the big manufacturer] came along in a sort of rotation. Mr. Chase was on one side and this Mr. Knox was on the other, and as each man came up they would take hold of the ticket that the man had, and say, “That is right, pass on.” Another would come would come up and they would say, “That is right, pass on.” Another would come up, and they would say, “Hold on, that is not the vote that you want to cast.” “Why, yes, it is the vote I want to cast.” “No, it is not.” “Why certainly this is my vote.” “O, no”; and he got it out of the man’s hand, tore it up, and threw it on the floor. He said, “You do not want to vote such a damned vote as that.” He then handed the voter another one. The man then remarked, “I don’t want to cast this vote.” The reply was, “Go right along’ that is the vote you want.” The man went right along and put it in the box. Mr. Hastings, the constable, stood right opposite, and I stood, perhaps, four feet from this Mr. Knox.United States Congress 1880

My attention was called to the peculiar way they had of managing the voters there, I stepped up to the little railing that they had there to go around and up to the polls and I saw two men stationed at the entrance where the voters went it. One was a Mr. Chase, and the other was a Mr. Knox. I saw that the help of the village [employees/thugs of the big manufacturer] came along in a sort of rotation. Mr. Chase was on one side and this Mr. Knox was on the other, and as each man came up they would take hold of the ticket that the man had, and say, “That is right, pass on.” Another would come would come up and they would say, “That is right, pass on.” Another would come up, and they would say, “Hold on, that is not the vote that you want to cast.” “Why, yes, it is the vote I want to cast.” “No, it is not.” “Why certainly this is my vote.” “O, no”; and he got it out of the man’s hand, tore it up, and threw it on the floor. He said, “You do not want to vote such a damned vote as that.” He then handed the voter another one. The man then remarked, “I don’t want to cast this vote.” The reply was, “Go right along’ that is the vote you want.” The man went right along and put it in the box. Mr. Hastings, the constable, stood right opposite, and I stood, perhaps, four feet from this Mr. Knox.United States Congress 1880

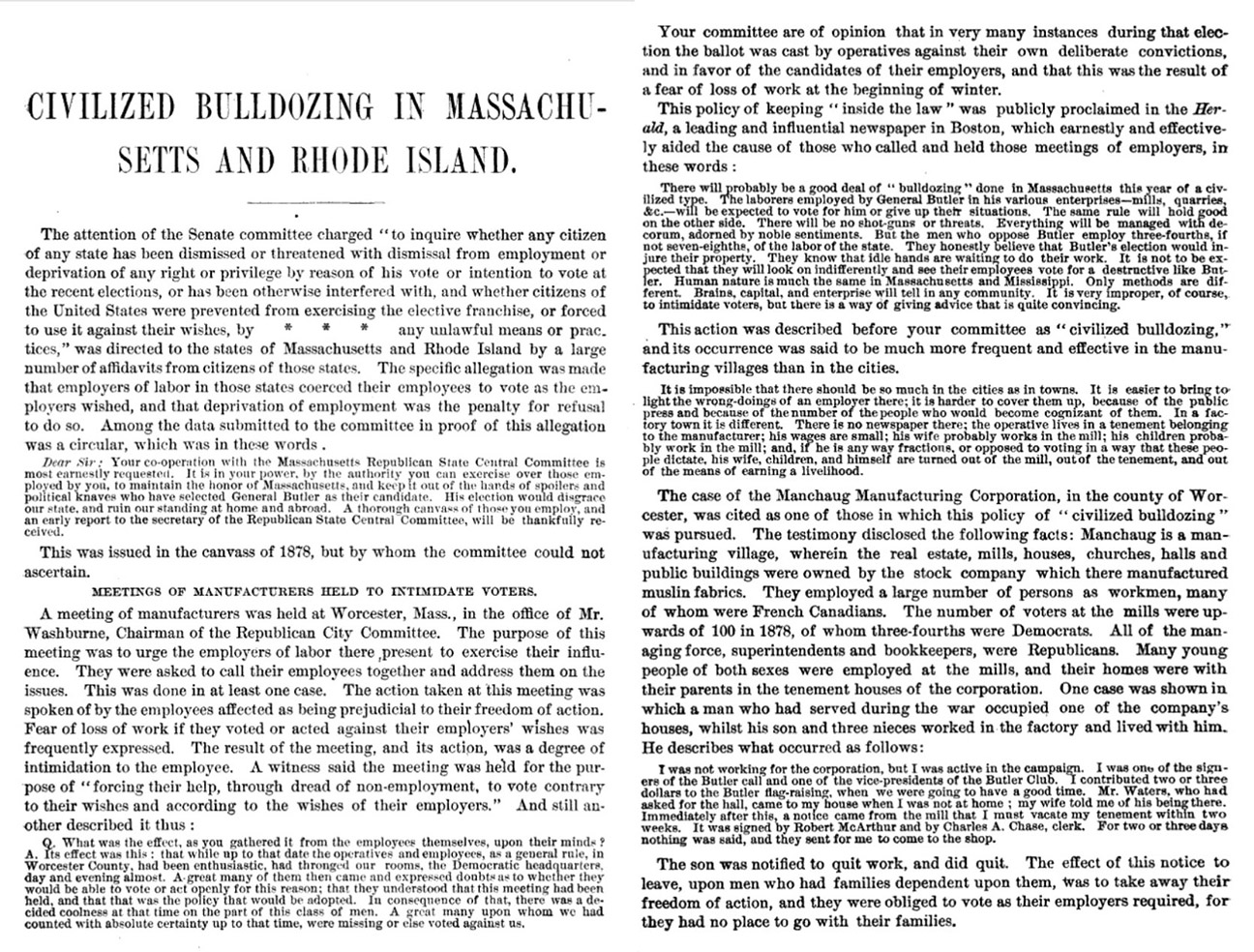

Civilized Bulldozing - Alleged Frauds in the Late Elections

US Congress Report 1880 - Civilized Bulldozing in Massachusetts and Rhode Island

At Middlesex, in 1768, gangs of roughs, said to have been hired at a guinea a day, attacked Wilkite radicals at the [open ballot] poll, killing one man, and struck fear into the general populace by assaulting men and women indiscriminately in the street. Similarly, at Westminster in 1784 the Foxites alleged that ‘banditti... armed with bludgeons, staves and pistols’ violently attacked their supporters, leaving many wounded and one dead.Jon Lawrence 2009

At Middlesex, in 1768, gangs of roughs, said to have been hired at a guinea a day, attacked Wilkite radicals at the [open ballot] poll, killing one man, and struck fear into the general populace by assaulting men and women indiscriminately in the street. Similarly, at Westminster in 1784 the Foxites alleged that ‘banditti... armed with bludgeons, staves and pistols’ violently attacked their supporters, leaving many wounded and one dead.Jon Lawrence 2009

Electing Our Masters: The Hustings in British Politics from Hogarth to Blair

Adoption of vote secrecy stands as one the most important reforms in modern Western democracy, due largely to its protection of voters from unscrupulous political machines.Scott M. Guenther 2016

Adoption of vote secrecy stands as one the most important reforms in modern Western democracy, due largely to its protection of voters from unscrupulous political machines.Scott M. Guenther 2016

Voting Alone: The Effects of Secret Voting Procedures on Political Behavior

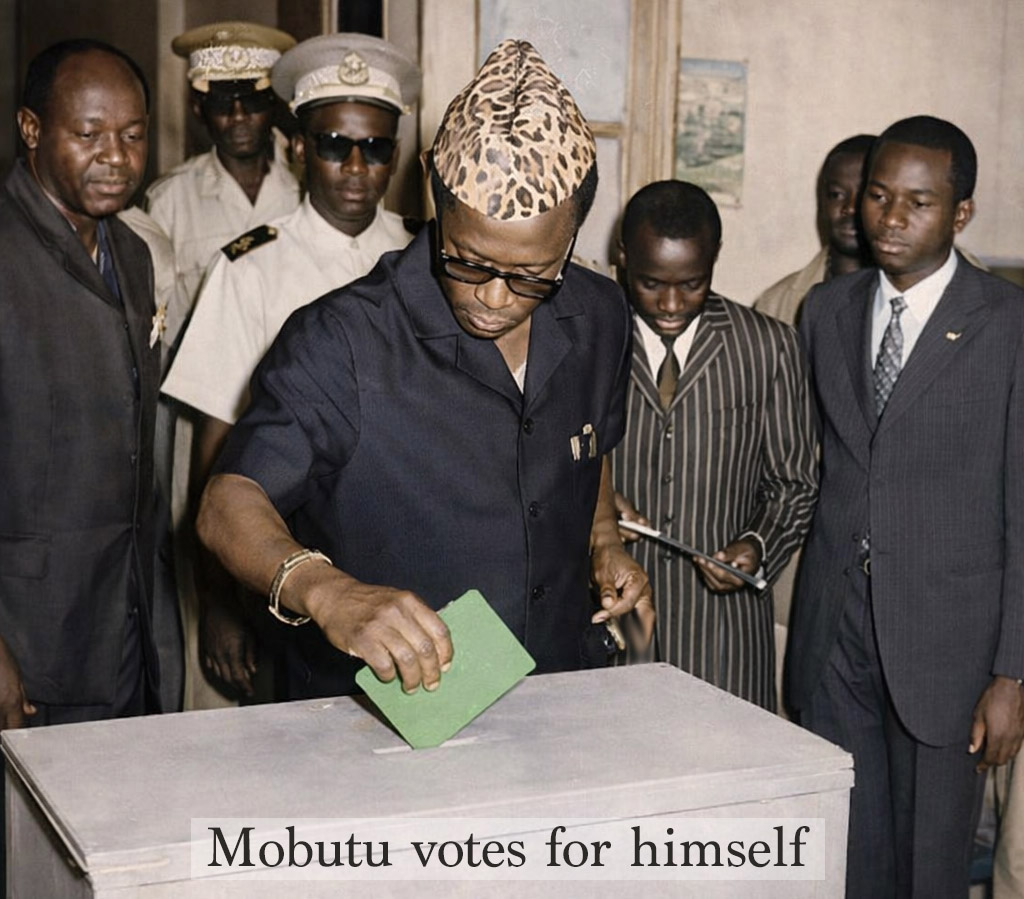

Steve Wilson 1984 - In Zaire’s Election, Choice Is Limited: Green Card or Red?

When casting his ballot, president, Mobutu Sese Sseko, votes in front of the cameras. He rips up a red ballot ‘le chaos’ and casts a green one ‘pour l’espoir’ - for himself. He was the only candidate from 1970 through 1980s and most open-ballot polling stations had no red cards. In the end, support for the red card fizzled. A visit to the polls showed one possible reason. One of the election officials, sat with a stack of green cards on his desk; there weren’t any red cards in sight. A soldier in green fatigues stood at the doorway. “We don’t need red cards here because nobody asks for one,” says Citizen Simba. “President Mobutu has decreed that Zairians must call one another citizen and use African names.” At a second polling place, again there are no red ballots. No demand, says Citizen Mbangala Mbe Lokoya, the local party official. “Everyone wants Mobutu.” The word went around Kinshasa that the bishop of Kisangani, a northern city, ripped up the green card sent to him and demanded a red one. Asked about the absence of red ballots, President Mobutu says some election officials hid red ballots because they felt that having them out in the open would be “a provocation.”

The particularly unruly election of 1882 even provided the chaotic backdrop for the culmination of the Hatfield-McCoy feud, an infamous and often bloody conflict between two rural families in eastern Kentucky. The election day festivities quickly turned sour when the Hatfield and McCoy sons got into a drunken brawl; Ellison Hatfield was mortally wounded, and his brothers shot the three McCoy men in retaliation. Though this incident was particularly egregious, it exemplified to reformists the need to establish order at the polls.Kate Keller 2018

The particularly unruly election of 1882 even provided the chaotic backdrop for the culmination of the Hatfield-McCoy feud, an infamous and often bloody conflict between two rural families in eastern Kentucky. The election day festivities quickly turned sour when the Hatfield and McCoy sons got into a drunken brawl; Ellison Hatfield was mortally wounded, and his brothers shot the three McCoy men in retaliation. Though this incident was particularly egregious, it exemplified to reformists the need to establish order at the polls.Kate Keller 2018

Why Are There Laws That Restrict What People Can Wear to the Polls?

As occurs so often in the course of American reform movements, light is presented as the solution to corruption which occurs in secret and in darkness: light is the great disinfectant. But of course what that reasoning applied to this circumstance meant was that every individual vote would be an even more visible, even more a public declaration for any interested observer to see, just as any observer at a viva voce election could hear every vote. Transparency, not secrecy, was the solution to the ills of American politics. It would take another generation for the opposite view to take hold: that the solution to the ills of American politics was secrecy, not visibility and not transparency, but voting as a private act and a ballot box that shielded every vote from scrutiny.Donald A. Debats 2016

As occurs so often in the course of American reform movements, light is presented as the solution to corruption which occurs in secret and in darkness: light is the great disinfectant. But of course what that reasoning applied to this circumstance meant was that every individual vote would be an even more visible, even more a public declaration for any interested observer to see, just as any observer at a viva voce election could hear every vote. Transparency, not secrecy, was the solution to the ills of American politics. It would take another generation for the opposite view to take hold: that the solution to the ills of American politics was secrecy, not visibility and not transparency, but voting as a private act and a ballot box that shielded every vote from scrutiny.Donald A. Debats 2016

Voting Viva Voce - Unlocking the Social Logic of Past Politics

The glass urn ballot box - relic of days when Tweed ruled city 1927

If the dependent relations are such that the individual voter in any considerable number or to any great degree is afraid of the public ballot, and either abstains from voting or votes contrary to his convictions, then the secret ballot is the lesser evil.John Stuart Mill 1861

If the dependent relations are such that the individual voter in any considerable number or to any great degree is afraid of the public ballot, and either abstains from voting or votes contrary to his convictions, then the secret ballot is the lesser evil.John Stuart Mill 1861

Terrorism Admitted on All Sides

[Deaths, Violence, Murder, Intimidation, Threats all grossly underreported] Previous quantification attempts have relied on counts of incidents of violence from selected samples of the press, an approach which has unsurprisingly produced substantial underestimations. For example, Cornelius O’Leary counted ten riots in 1874, whereas we find twenty-six. Donald Richter’s dedicated studies of 1971 and 1981 find ‘no recorded fatalities’ nationally during the years 1865–85, whereas we uncover (for England and Wales alone) at least thirty-nine. Richter finds just seventy-one separate incidents of serious disorder in this period, whereas we find at least 599 riots or disturbances (alongside a further 812 isolated incidents). Blaxill, Luke; Cohen, Gidon; Hutchison, Gary; Kuhn, Patrick M; Vivyan, Nick 2024

[Deaths, Violence, Murder, Intimidation, Threats all grossly underreported] Previous quantification attempts have relied on counts of incidents of violence from selected samples of the press, an approach which has unsurprisingly produced substantial underestimations. For example, Cornelius O’Leary counted ten riots in 1874, whereas we find twenty-six. Donald Richter’s dedicated studies of 1971 and 1981 find ‘no recorded fatalities’ nationally during the years 1865–85, whereas we uncover (for England and Wales alone) at least thirty-nine. Richter finds just seventy-one separate incidents of serious disorder in this period, whereas we find at least 599 riots or disturbances (alongside a further 812 isolated incidents). Blaxill, Luke; Cohen, Gidon; Hutchison, Gary; Kuhn, Patrick M; Vivyan, Nick 2024

Electoral Violence in England and Wales, 1832–1914

[With the introduction of the secret ballot] the day of polling saw such quietness that a stranger would not realize that an election was going on. Rioting and disorder disappeared entirely. Intimidation by landlords and dictation by trades unions alike ceased.John Henry Wigmore 1889

[With the introduction of the secret ballot] the day of polling saw such quietness that a stranger would not realize that an election was going on. Rioting and disorder disappeared entirely. Intimidation by landlords and dictation by trades unions alike ceased.John Henry Wigmore 1889

The Australian Ballot System

By compelling the dishonest man to mark his vote in secrecy, it renders it impossible for him to prove his dishonesty, and thus deprives him of the market for it.John Henry Wigmore 1889

By compelling the dishonest man to mark his vote in secrecy, it renders it impossible for him to prove his dishonesty, and thus deprives him of the market for it.John Henry Wigmore 1889

The Australian Ballot System

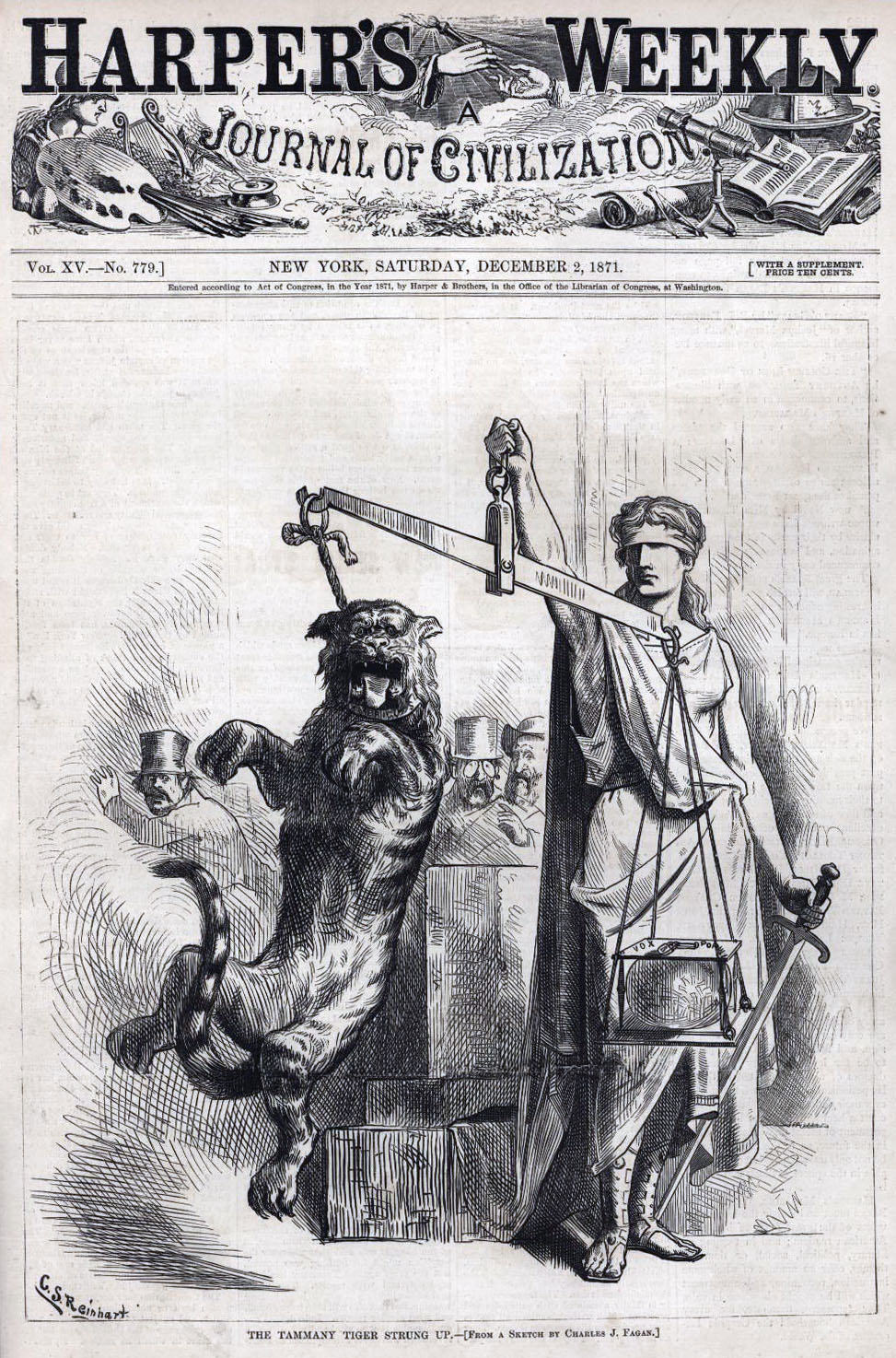

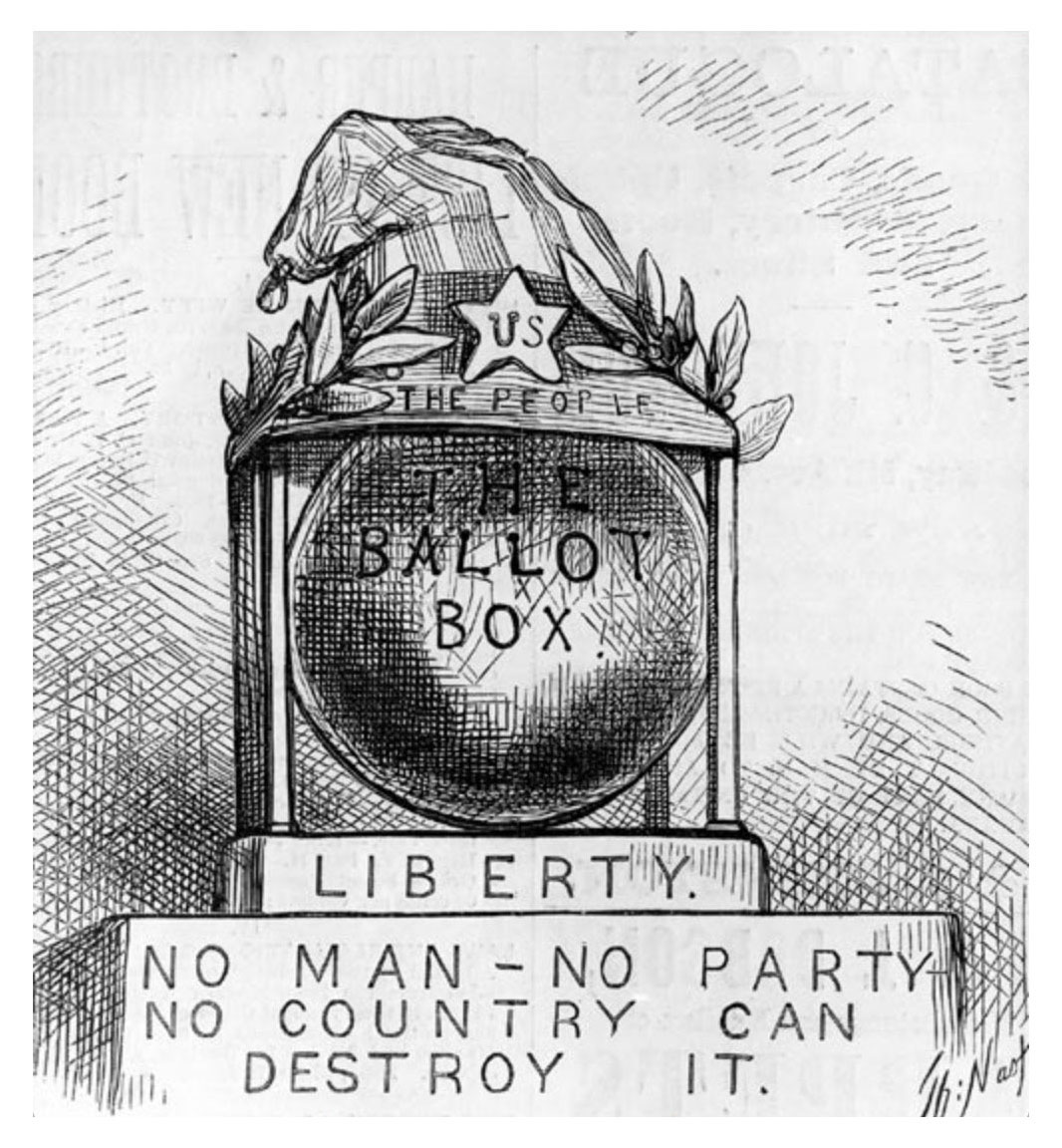

“Tammany Tiger Strung Up” by voting reform - 1871

Today, virtually every democracy makes overt vote buying illegal and discourages it through mechanisms like the secret ballot.Francis Fukuyama 2014

Today, virtually every democracy makes overt vote buying illegal and discourages it through mechanisms like the secret ballot.Francis Fukuyama 2014

Political Order and Political Decay

The absence of a secret ballot magnified corruption, [and] enhanced party control.Maria Petrova 2011

The absence of a secret ballot magnified corruption, [and] enhanced party control.Maria Petrova 2011

Newspapers and Parties

Voting procedure is open in the USSR, but the ballot is designated secret by the law (article 95 of the constitution); however, anyone who makes use of the procedure for casting his vote secretly is noted by the electoral officer, and disciplined accordingly.Roger Scruton 1982

Voting procedure is open in the USSR, but the ballot is designated secret by the law (article 95 of the constitution); however, anyone who makes use of the procedure for casting his vote secretly is noted by the electoral officer, and disciplined accordingly.Roger Scruton 1982

A Dictionary of Political Thought

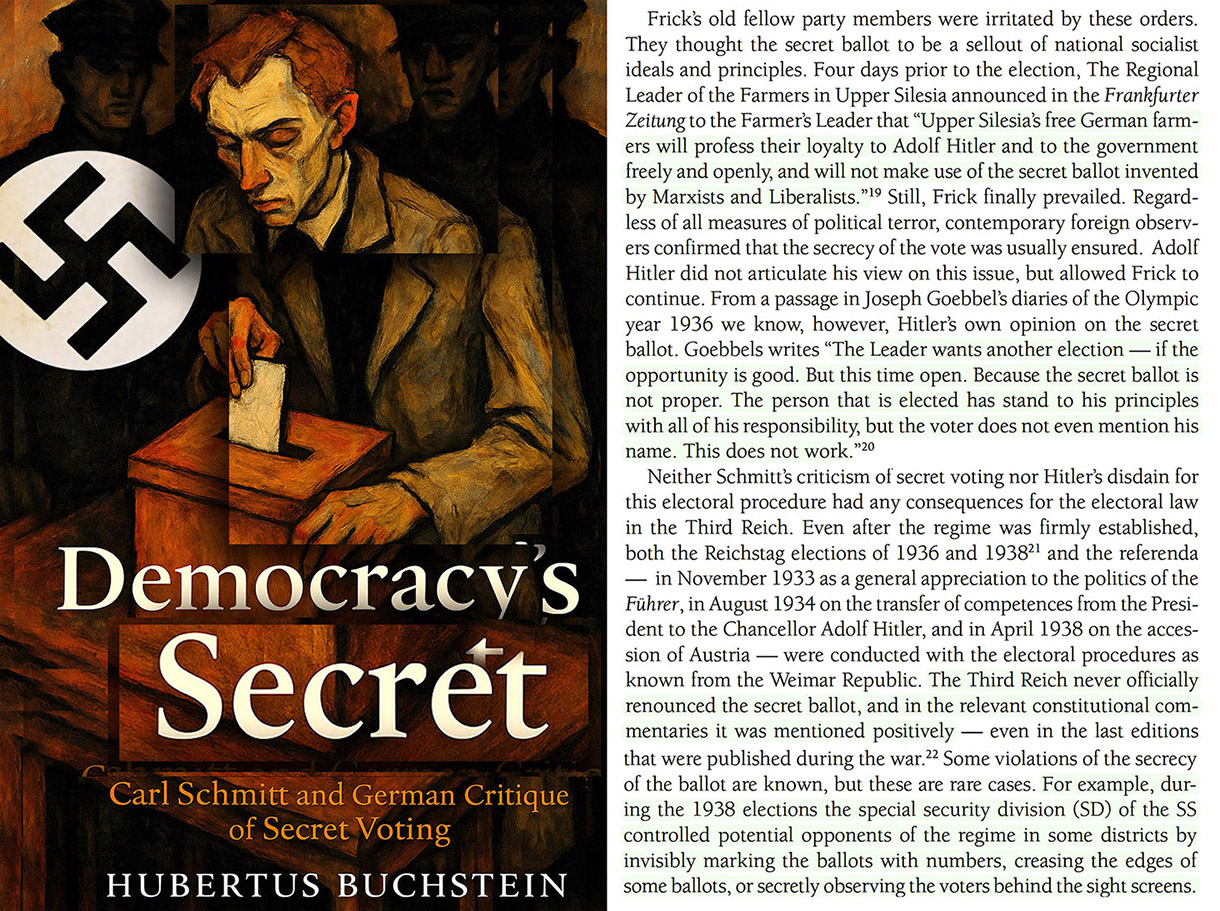

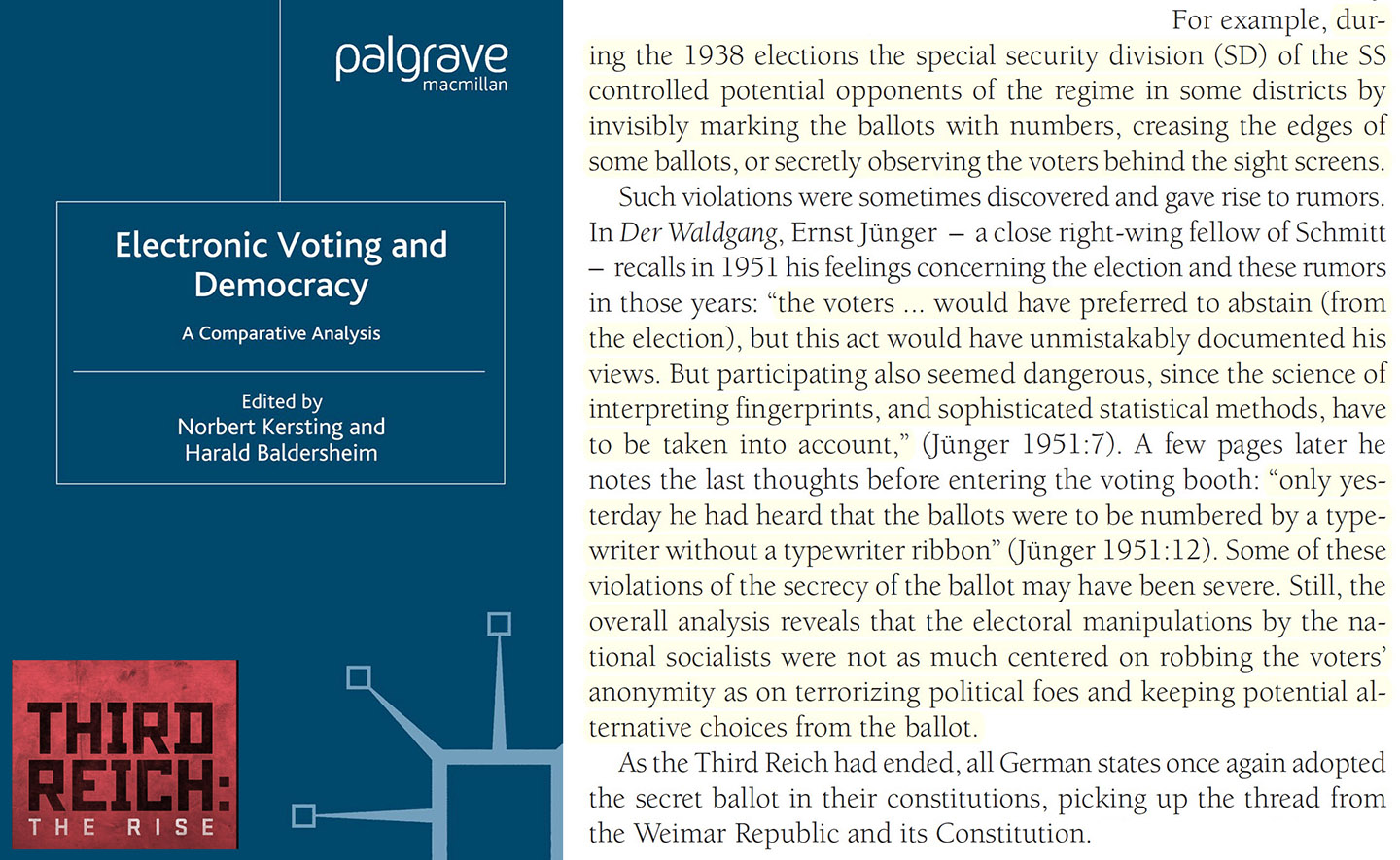

Hubertus Buchstein 2002 - Democracy’s Secret

Frick’s old fellow party members were irritated by these orders. They thought the secret ballot to be a sellout of national socialist ideals and principles. Four days prior to the election, The Regional Leader of the Farmers in Upper Silesia announced in the Frankfurter Zeitung to the Farmer’s Leader that “Upper Silesia’s free German farmers will profess their loyalty to Adolf Hitler and to the government freely and openly, and will not make use of the secret ballot invented by Marxists and Liberalists.”19 Still, Frick finally prevailed. Regardless of all measures of political terror, contemporary foreign observers confirmed that the secrecy of the vote was usually ensured. Adolf Hitler did not articulate his view on this issue, but allowed Frick to continue. From a passage in Joseph Goebbel’s diaries of the Olympic year 1936 we know, however, Hitler’s own opinion on the secret ballot. Goebbels writes “The Leader wants another election — if the opportunity is good. But this time open. Because the secret ballot is not proper. The person that is elected has stand to his principles with all of his responsibility, but the voter does not even mention his name. This does not work.”20 Neither Schmitt’s criticism of secret voting nor Hitler’s disdain for this electoral procedure had any consequences for the electoral law in the Third Reich. Even after the regime was firmly established, both the Reichstag elections of 1936 and 193821 and the referenda — in November 1933 as a general appreciation to the politics of the Führer, in August 1934 on the transfer of competences from the President to the Chancellor Adolf Hitler, and in April 1938 on the accession of Austria — were conducted with the electoral procedures as known from the Weimar Republic. The Third Reich never officially renounced the secret ballot, and in the relevant constitutional commentaries it was mentioned positively — even in the last editions that were published during the war.22 Some violations of the secrecy of the ballot are known, but these are rare cases. For example, during the 1938 elections the special security division (SD) of the SS controlled potential opponents of the regime in some districts by invisibly marking the ballots with numbers, creasing the edges of some ballots, or secretly observing the voters behind the sight screens.

The Ballot was nothing without secrecy.Sir Robert Peel 1833

The Ballot was nothing without secrecy.Sir Robert Peel 1833

House of Commons - Election by Ballot

The view is widespread that more transparency in institutions leads to better outcomes. That, however, is surely too enthusiastic a view. To illustrate, a sine qua non of popular democracy is the secret ballot — the suppression of transparency. To appreciate one of the central virtues of secret balloting, consider the fact that in a number of organizations, the leadership, for obvious reasons, insists that the preferences and opinions of the rank and file be revealed through a hand count instead of a secret ballot. Transparency, in that case, is a way of controlling the membership.Albert Breton 2007

The view is widespread that more transparency in institutions leads to better outcomes. That, however, is surely too enthusiastic a view. To illustrate, a sine qua non of popular democracy is the secret ballot — the suppression of transparency. To appreciate one of the central virtues of secret balloting, consider the fact that in a number of organizations, the leadership, for obvious reasons, insists that the preferences and opinions of the rank and file be revealed through a hand count instead of a secret ballot. Transparency, in that case, is a way of controlling the membership.Albert Breton 2007

The Economics of Transparency in Politics

The adoption of the secret ballot dramatically reduced instances of electoral coercion. Researchers found that indicators of electoral corruption dropped – such as prices offered by those seeking to buy votes, the frequency of petitions challenging electoral results, and the rates at which incumbents are reelected.Susan Orr & James Johnson 2020

The adoption of the secret ballot dramatically reduced instances of electoral coercion. Researchers found that indicators of electoral corruption dropped – such as prices offered by those seeking to buy votes, the frequency of petitions challenging electoral results, and the rates at which incumbents are reelected.Susan Orr & James Johnson 2020

Perils of voting without secrecy

There will be a good deal of ‘bull-dozing’ down in Massachusetts this year of a civilized type. The laborers employed by General Butler in his various enterprises—mills, quarries, etc.—will be expected to vote for him or to give up their situations. The same rule will hold good on the other side. There will be no shotguns or threats. Everything will be managed with decorum, adorned with noble sentiments. But the men who oppose Butler employ three-fourths, if not seven-eighths, of the laborers of the state. They honestly believe that Butler’s election would injure their property. They know that idle hands are waiting to do their work. It is not the be expected that they will look on indifferently and see their employees vote for a destructive like Butler. Human nature is much the same in Massachusetts and Mississippi. Only methods are different. Brains, capital, and enterprise will tell in any community. It is very improper to intimidate voters, but there is a way of giving advice that is most convincingUnited States Congress 1880

There will be a good deal of ‘bull-dozing’ down in Massachusetts this year of a civilized type. The laborers employed by General Butler in his various enterprises—mills, quarries, etc.—will be expected to vote for him or to give up their situations. The same rule will hold good on the other side. There will be no shotguns or threats. Everything will be managed with decorum, adorned with noble sentiments. But the men who oppose Butler employ three-fourths, if not seven-eighths, of the laborers of the state. They honestly believe that Butler’s election would injure their property. They know that idle hands are waiting to do their work. It is not the be expected that they will look on indifferently and see their employees vote for a destructive like Butler. Human nature is much the same in Massachusetts and Mississippi. Only methods are different. Brains, capital, and enterprise will tell in any community. It is very improper to intimidate voters, but there is a way of giving advice that is most convincingUnited States Congress 1880

Civilized Bulldozing - Alleged Frauds in the Late Elections

A Prophetic Picture - The Ballot Blows out Spoils 1881 - Harpers

By compelling the honest man to vote in secrecy it relieves him not merely from the grosser forms of intimidation, but from more subtle and perhaps more pernicious coercion of every sort.John Henry Wigmore 1889

By compelling the honest man to vote in secrecy it relieves him not merely from the grosser forms of intimidation, but from more subtle and perhaps more pernicious coercion of every sort.John Henry Wigmore 1889

The Australian Ballot System

Ever since its first days, indeed, in the time of Henry VI., the open poll had shown its failings. One is half amused to read the ingenuous complaint presented in 1451 by certain freemen of Huntingdonshire, protesting against the election of two knights returned for the shire, and telling a tale of armed opponents, who threatened violence at the polls, “and soe wee departed for dread of the inconveniences that was likely to be done for manslaughter.” John Henry Wigmore 1889

Ever since its first days, indeed, in the time of Henry VI., the open poll had shown its failings. One is half amused to read the ingenuous complaint presented in 1451 by certain freemen of Huntingdonshire, protesting against the election of two knights returned for the shire, and telling a tale of armed opponents, who threatened violence at the polls, “and soe wee departed for dread of the inconveniences that was likely to be done for manslaughter.” John Henry Wigmore 1889

The Australian Ballot System

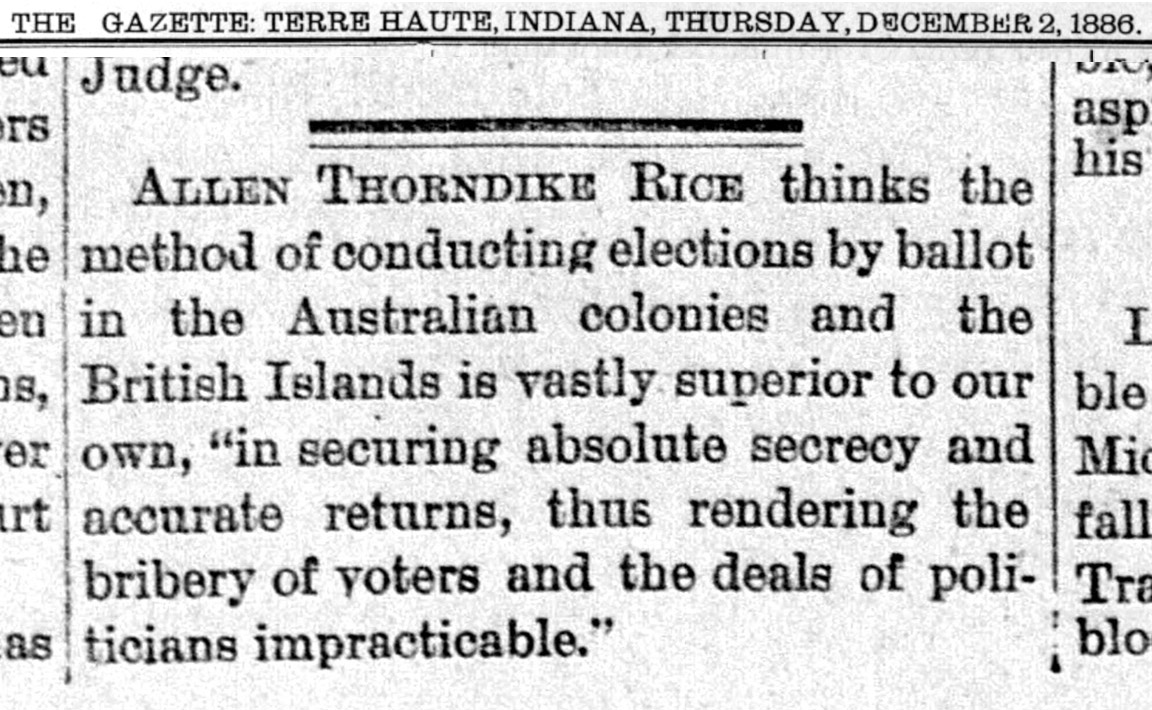

The extent and intensity of electoral and voter fraud that took place during the U.S. Gilded Age is properly infamous. This paper explores a form of voter intimidation that has garnered comparatively little scholarly attention: economic coercion. Absent secrecy at the polls and security at work, bosses forced workingmen to choose between their job or their vote. Economic voter intimidation provoked both a real and rhetorical crisis in the 1870s and 1880s. In real terms, it disrupted hundreds of elections and damaged thousands of workers’ livelihoods. It became a nationwide crisis after 1873, however, because for the first time, employers were coercing white workingmen on a widespread basis. Reports of employers coercing their employees at the polls throughout the nation confirmed the worst fears of many labor leaders and politicians: white wage-workers were insecure possessors of the franchise whose precariousness might threaten democracy itself. Mining previously overlooked accounts of economic voter intimidation in contested congressional election case records, congressional investigations, corporate records, and newspapers, this article argues that employers’ politicized layoff threats and observation of workers at the polls undermined the political equality of even those men whose whiteness had seemingly secured their privilege.Gideon Cohn-Postar 2021

The extent and intensity of electoral and voter fraud that took place during the U.S. Gilded Age is properly infamous. This paper explores a form of voter intimidation that has garnered comparatively little scholarly attention: economic coercion. Absent secrecy at the polls and security at work, bosses forced workingmen to choose between their job or their vote. Economic voter intimidation provoked both a real and rhetorical crisis in the 1870s and 1880s. In real terms, it disrupted hundreds of elections and damaged thousands of workers’ livelihoods. It became a nationwide crisis after 1873, however, because for the first time, employers were coercing white workingmen on a widespread basis. Reports of employers coercing their employees at the polls throughout the nation confirmed the worst fears of many labor leaders and politicians: white wage-workers were insecure possessors of the franchise whose precariousness might threaten democracy itself. Mining previously overlooked accounts of economic voter intimidation in contested congressional election case records, congressional investigations, corporate records, and newspapers, this article argues that employers’ politicized layoff threats and observation of workers at the polls undermined the political equality of even those men whose whiteness had seemingly secured their privilege.Gideon Cohn-Postar 2021

Vote for your Bread and Butter - Economic Intimidation of Voters in the Gilded Age

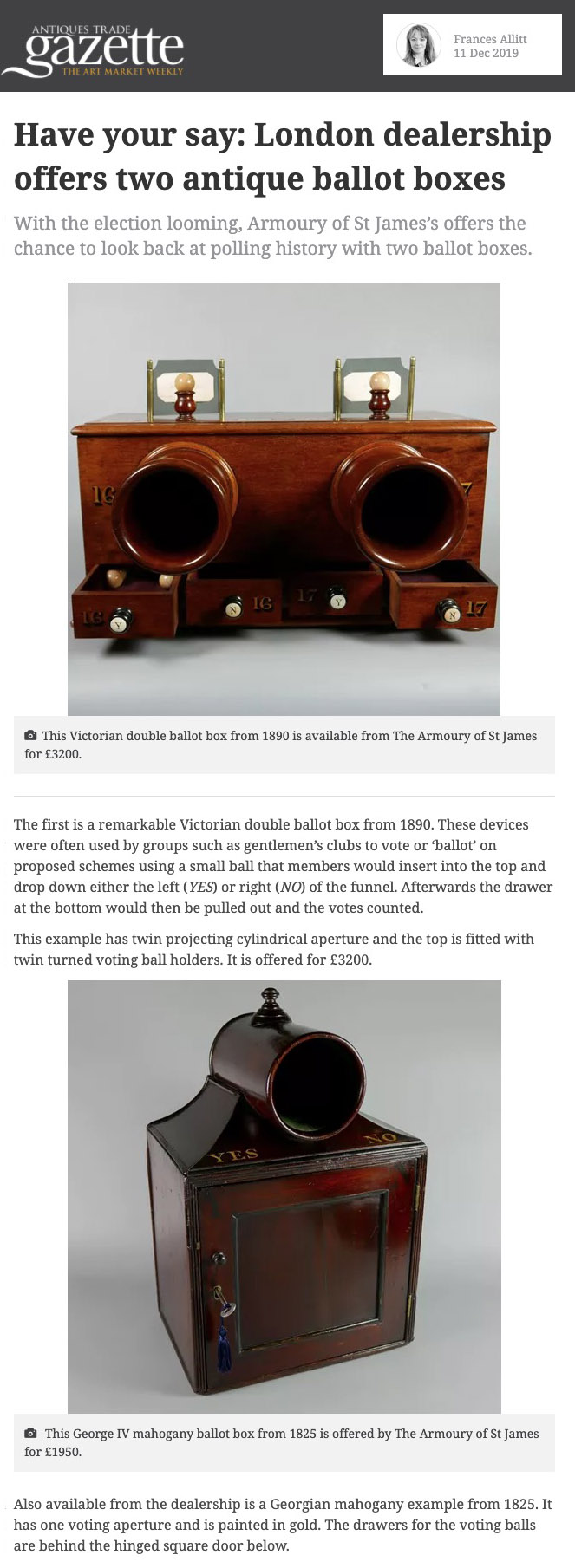

Victorian Era: Aristotle-style Ballot Box

Landlords intimidated their tenants, and marched detachments to the polls to vote in their interests. In one place employers coerced their workmen ; and in another the trades unions coerced their members. Worse than all, and hardly to be believed, in larger cities hired mobs often patrolled the streets, keeping away hostile voters and intimidating those who ventured to the polls. A Conservative mob or a Radical or Liberal mob, or both, were in some places a common feature of an election. On one occasion which may serve as an example, some 500 out of 2,000 Conservative voters were prevented by demonstrations of violence from giving their votes.John Henry Wigmore 1889

Landlords intimidated their tenants, and marched detachments to the polls to vote in their interests. In one place employers coerced their workmen ; and in another the trades unions coerced their members. Worse than all, and hardly to be believed, in larger cities hired mobs often patrolled the streets, keeping away hostile voters and intimidating those who ventured to the polls. A Conservative mob or a Radical or Liberal mob, or both, were in some places a common feature of an election. On one occasion which may serve as an example, some 500 out of 2,000 Conservative voters were prevented by demonstrations of violence from giving their votes.John Henry Wigmore 1889

The Australian Ballot System

The general and emphatic verdict was that a thorough change for the better had taken place. “All those disorders,” said Sir Joseph Heron, town clerk of Manchester, “that used to occur under open voting have ceased altogether.... Any one walking through the borough would not know the fact that an election was going on ; everything is so perfectly peaceful;” and yet “it was notorious that, taking the city as a whole, there was more interest felt in the elections than had been known for very many years past.” To the change in regard to the purity of the election he bears the strongest possible testimony: “I believe that such a thing as bribery does not exist at Manchester;” though it was in these large cities that the disorders of the previous decades had reached their extreme.” The ballot is a blessing to us.” John Henry Wigmore 1889

The general and emphatic verdict was that a thorough change for the better had taken place. “All those disorders,” said Sir Joseph Heron, town clerk of Manchester, “that used to occur under open voting have ceased altogether.... Any one walking through the borough would not know the fact that an election was going on ; everything is so perfectly peaceful;” and yet “it was notorious that, taking the city as a whole, there was more interest felt in the elections than had been known for very many years past.” To the change in regard to the purity of the election he bears the strongest possible testimony: “I believe that such a thing as bribery does not exist at Manchester;” though it was in these large cities that the disorders of the previous decades had reached their extreme.” The ballot is a blessing to us.” John Henry Wigmore 1889

The Australian Ballot System

David Eisenbach (Columbia) 2020

The Introduction of the Secret Ballot Link

The improvement in the protection of electoral secrecy had far-reaching consequences for political competition... These changes in the electoral law reduced the opportunities for electoral intimidation. By emboldening voters to take electoral risks, the Rickert law made possible the spectacular political growth of the Social Democratic Party during the final elections of the period. These gains for Social Democrats came at the expense of parties on the right. Because of the reduction in their ability to monitor voters’ choices, many candidates on the right lost districts that had previously been their electoral strongholds.Isabela Mares 2015

The improvement in the protection of electoral secrecy had far-reaching consequences for political competition... These changes in the electoral law reduced the opportunities for electoral intimidation. By emboldening voters to take electoral risks, the Rickert law made possible the spectacular political growth of the Social Democratic Party during the final elections of the period. These gains for Social Democrats came at the expense of parties on the right. Because of the reduction in their ability to monitor voters’ choices, many candidates on the right lost districts that had previously been their electoral strongholds.Isabela Mares 2015

From Open Secrets to Secret Voting

[Before the secret ballot] Candidates campaigned by offering money, food, or entertainment to voters. In addition to these positive inducements, electoral intimidation, pressure, and harassment were amply used during elections. Policemen, tax collectors, and other local notables were deployed to influence the decisions of voters to support particular candidates. Imperfections in voting technology allowed candidates and their agents to engage in intense monitoring of the political choices made by voters and to punish the latter for undesirable political choices. Such threats of post-electoral punishments were highly credible because of ample imperfections in voting technology. Isabela Mares 2015

[Before the secret ballot] Candidates campaigned by offering money, food, or entertainment to voters. In addition to these positive inducements, electoral intimidation, pressure, and harassment were amply used during elections. Policemen, tax collectors, and other local notables were deployed to influence the decisions of voters to support particular candidates. Imperfections in voting technology allowed candidates and their agents to engage in intense monitoring of the political choices made by voters and to punish the latter for undesirable political choices. Such threats of post-electoral punishments were highly credible because of ample imperfections in voting technology. Isabela Mares 2015

From Open Secrets to Secret Voting

The use of the secret ballot makes it impossible to tell whether voting promises are carried out. In these circumstances the voter will simply vote in accord with his preferences on each individual issue.Gordon Tullock 1959

The use of the secret ballot makes it impossible to tell whether voting promises are carried out. In these circumstances the voter will simply vote in accord with his preferences on each individual issue.Gordon Tullock 1959

Problems of Majority Voting

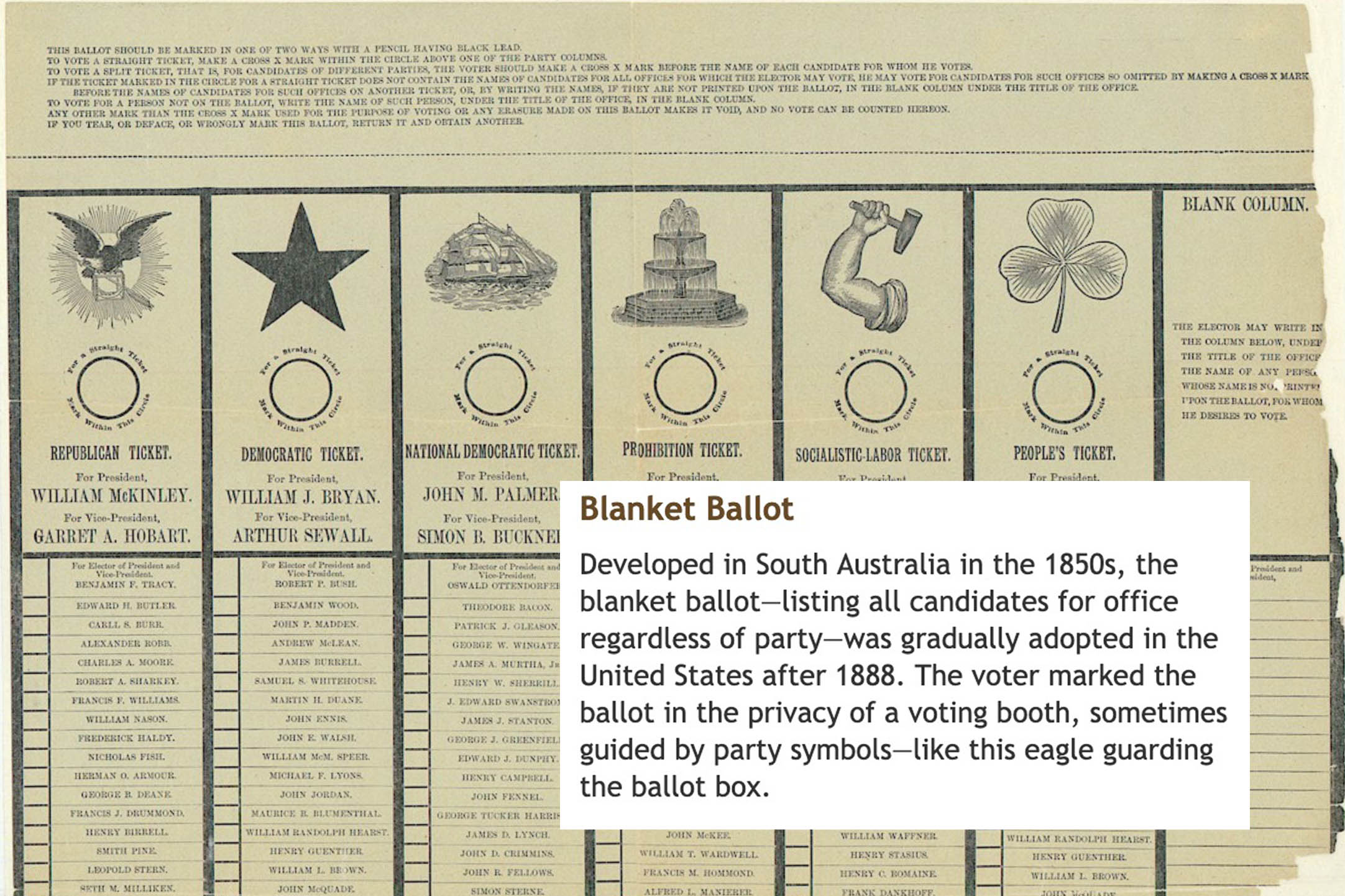

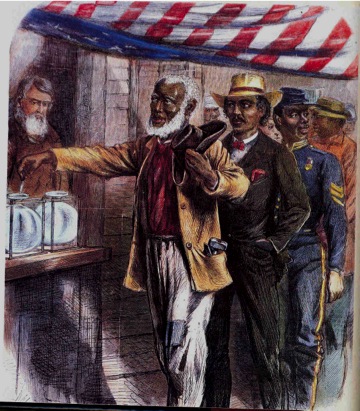

In 1856 the state of Victoria, which had been carved out of New South Wales in 1851, and the state of Tasmania would become the first places in the world to introduce an effective secret ballot in elections, which stopped vote buying and coercion. Today we still call the standard method of achieving secrecy in voting in elections the Australian ballot.Daron Acemoglu, James A. Robinson 2012

In 1856 the state of Victoria, which had been carved out of New South Wales in 1851, and the state of Tasmania would become the first places in the world to introduce an effective secret ballot in elections, which stopped vote buying and coercion. Today we still call the standard method of achieving secrecy in voting in elections the Australian ballot.Daron Acemoglu, James A. Robinson 2012

Why Nations Fail

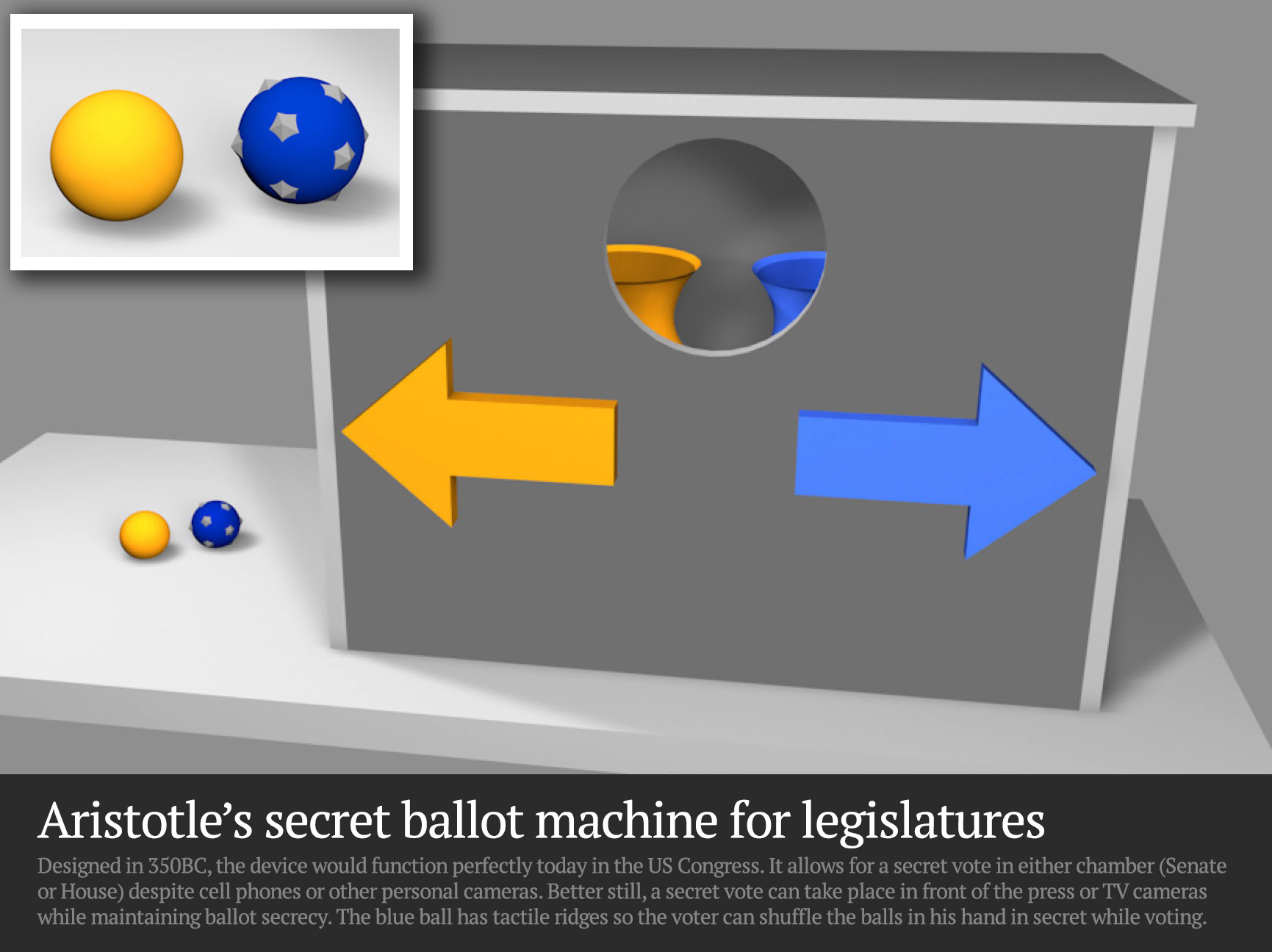

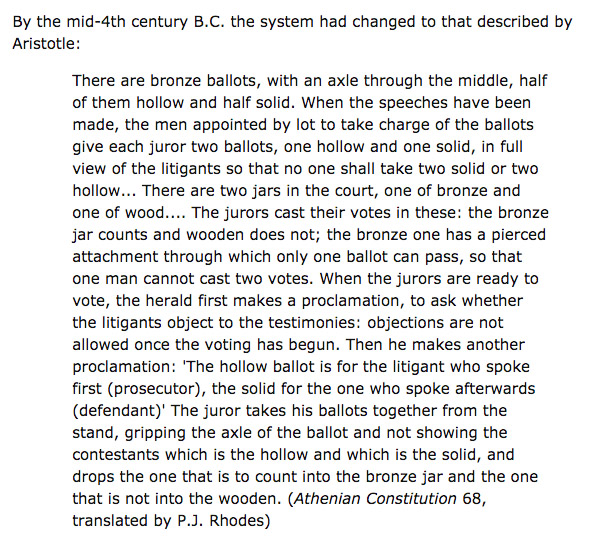

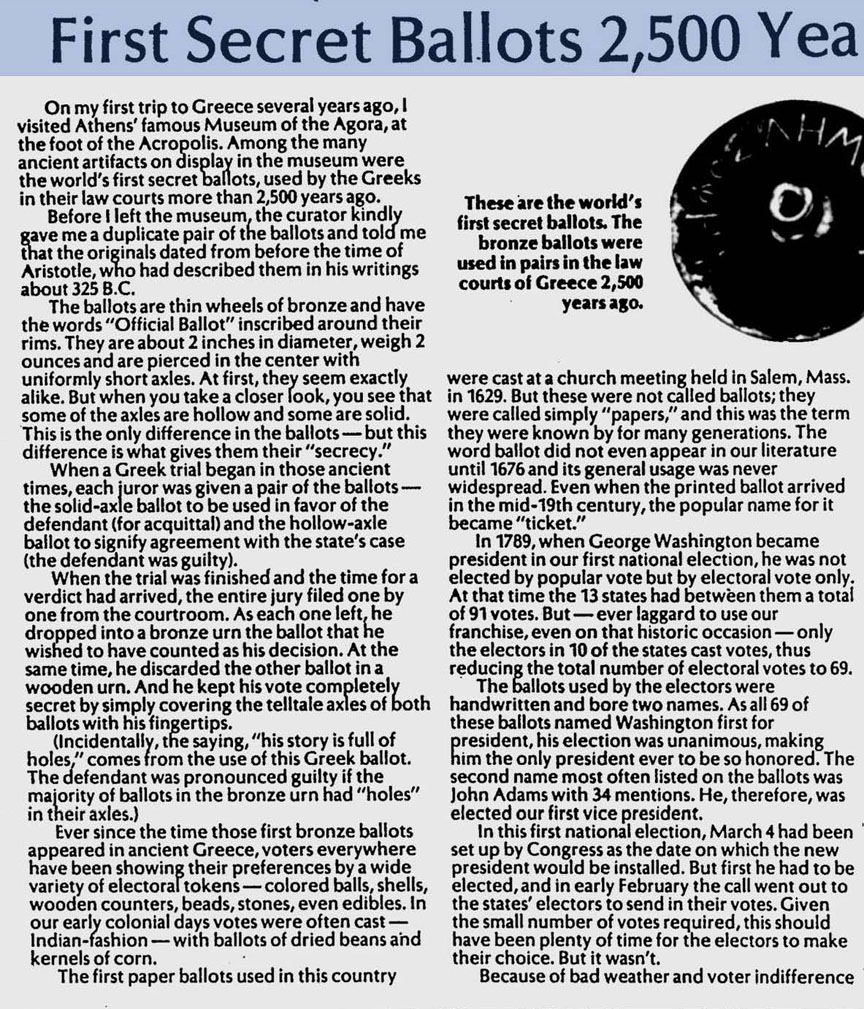

Aristotle’s Secret Voting ‘Machine’ 350BC

3-D drawing by James D’Angelo made from Aristotle’s notes on a dual urn secret voting system. To use, the voter grabs both of the ballots (balls) in one hand and inserts their hand in the hole. To vote yes, they put the yellow ball in the yellow urn and the blue ball in the blue urn. To vote no, they do the opposite. The blue ball is grooved so it can be distinguished by touch alone. This system allows for observers to monitor the voting process while still keeping the vote secret. A the end of the vote, the urns are overturned in public and the votes counted. It is an ideal system for legislatures, where the number of votes are small – and it eliminates the ability to record the vote with cellphones.

“Any election I work in, I’ve got money. Generally there’s somebody buying votes against me. The person who gets ‘em (wins the election) is the one who pays the most, and I generally have it (the most money).” But Fugate never pays off until he has actually seen the bought vote cast, or else casts it himself. “You don’t give nobody money unless you watch ‘em. I go to the house, line ‘em up. On Election Day, I vote ‘em. They let me vote ‘em any way I want to. If they want to vote themselves, they won’t get no money from me. I wouldn’t trust ‘em if I couldn’t watch ‘em vote.”

“Any election I work in, I’ve got money. Generally there’s somebody buying votes against me. The person who gets ‘em (wins the election) is the one who pays the most, and I generally have it (the most money).” But Fugate never pays off until he has actually seen the bought vote cast, or else casts it himself. “You don’t give nobody money unless you watch ‘em. I go to the house, line ‘em up. On Election Day, I vote ‘em. They let me vote ‘em any way I want to. If they want to vote themselves, they won’t get no money from me. I wouldn’t trust ‘em if I couldn’t watch ‘em vote.”

By law, only voters who swear they cannot read, are blind or suffer from some other physical disability requiring assistance can legally receive aid In the voting booth. Such voters generally are assisted by one of two precinct officials while the other observes. But if the voter prefers, he can be assisted by a person of his choice. Under state law, an individual can assist only two voters in any election. In years past, Fugate and others have been able to perpetrate widespread fraud by II assisting II dozens of voters actually casting their votes In exchange for giving them money.R.G. Dunlop 1987

A Vote-buyer on his Trade - to Win you have to do it

The Plug Uglies were excellent intimidators of voters. With their bloody help, the American Party in 1857, for example, won 19 of 20 wards in Baltimore with 76 percent of the vote and took control of the city and state government. Baltimore roughs were so good, they were recruited to control voting in Philadelphia and Washington, D.C.Carl Schoettler 2006

The Plug Uglies were excellent intimidators of voters. With their bloody help, the American Party in 1857, for example, won 19 of 20 wards in Baltimore with 76 percent of the vote and took control of the city and state government. Baltimore roughs were so good, they were recruited to control voting in Philadelphia and Washington, D.C.Carl Schoettler 2006

Think Baltimore's rough now?

Anderson and Tollison (1990) … argue that the poor used the secrecy provided by the Australian Ballot to vote in their own interest. As rational wealth-maximizers, they voted for expansionary government policies in the form of redistribution.Jac C. Heckelman 1995

Anderson and Tollison (1990) … argue that the poor used the secrecy provided by the Australian Ballot to vote in their own interest. As rational wealth-maximizers, they voted for expansionary government policies in the form of redistribution.Jac C. Heckelman 1995

The effect of the secret ballot on voter turnout rates

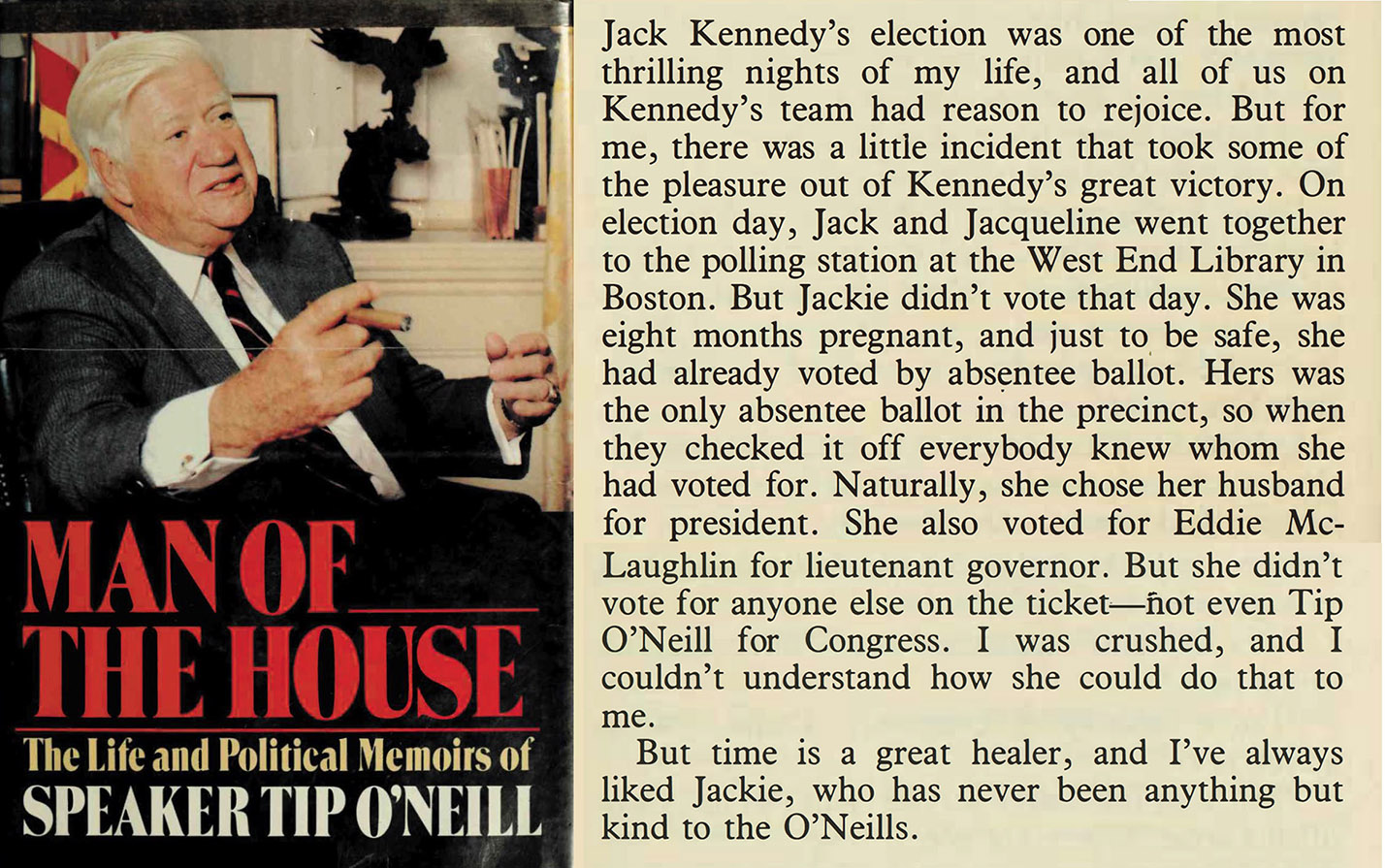

Perils of voting without secrecy: Before modern voting procedures were created, there was a lively trade in votes. Employers, landlords, political operatives and even clergy exerted their influence on people who had to vote by voice or public show of hands. In places that used paper ballots, party agents handed out pre-marked, color-coded party “tickets” and watched as voters dropped them in the ballot boxes. People could be – and were – bribed and threatened into voting for particular candidates, regardless of their personal views on the candidates or the issues.Susan Orr & James Johnson 2020

Perils of voting without secrecy: Before modern voting procedures were created, there was a lively trade in votes. Employers, landlords, political operatives and even clergy exerted their influence on people who had to vote by voice or public show of hands. In places that used paper ballots, party agents handed out pre-marked, color-coded party “tickets” and watched as voters dropped them in the ballot boxes. People could be – and were – bribed and threatened into voting for particular candidates, regardless of their personal views on the candidates or the issues.Susan Orr & James Johnson 2020

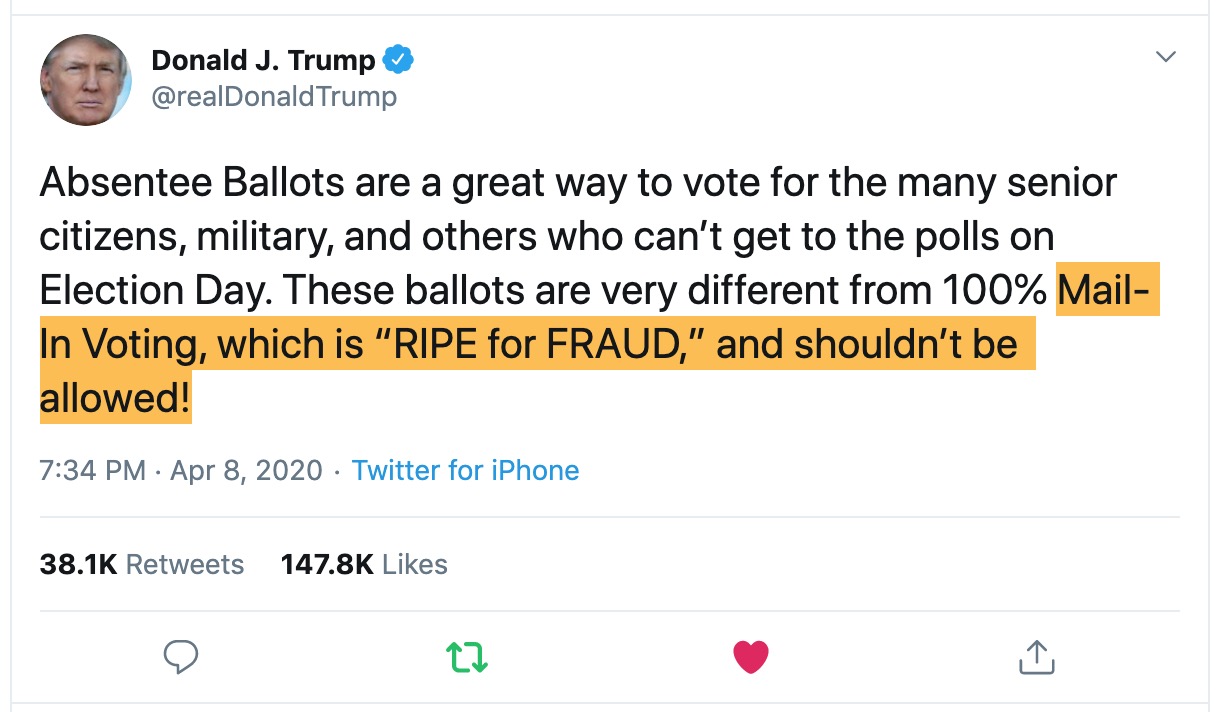

Voting by mail is convenient, but not always secret

Other forms of intimidation may be even more difficult to identify. How could anyone uncover the subtle – or not so subtle – influence exerted at the kitchen table by an abusive spouse or domineering parent, when the family sits down to vote? It happens all over the world in places where ballots are not secret.Susan Orr & James Johnson 2020

Other forms of intimidation may be even more difficult to identify. How could anyone uncover the subtle – or not so subtle – influence exerted at the kitchen table by an abusive spouse or domineering parent, when the family sits down to vote? It happens all over the world in places where ballots are not secret.Susan Orr & James Johnson 2020

Voting by mail is convenient, but not always secret

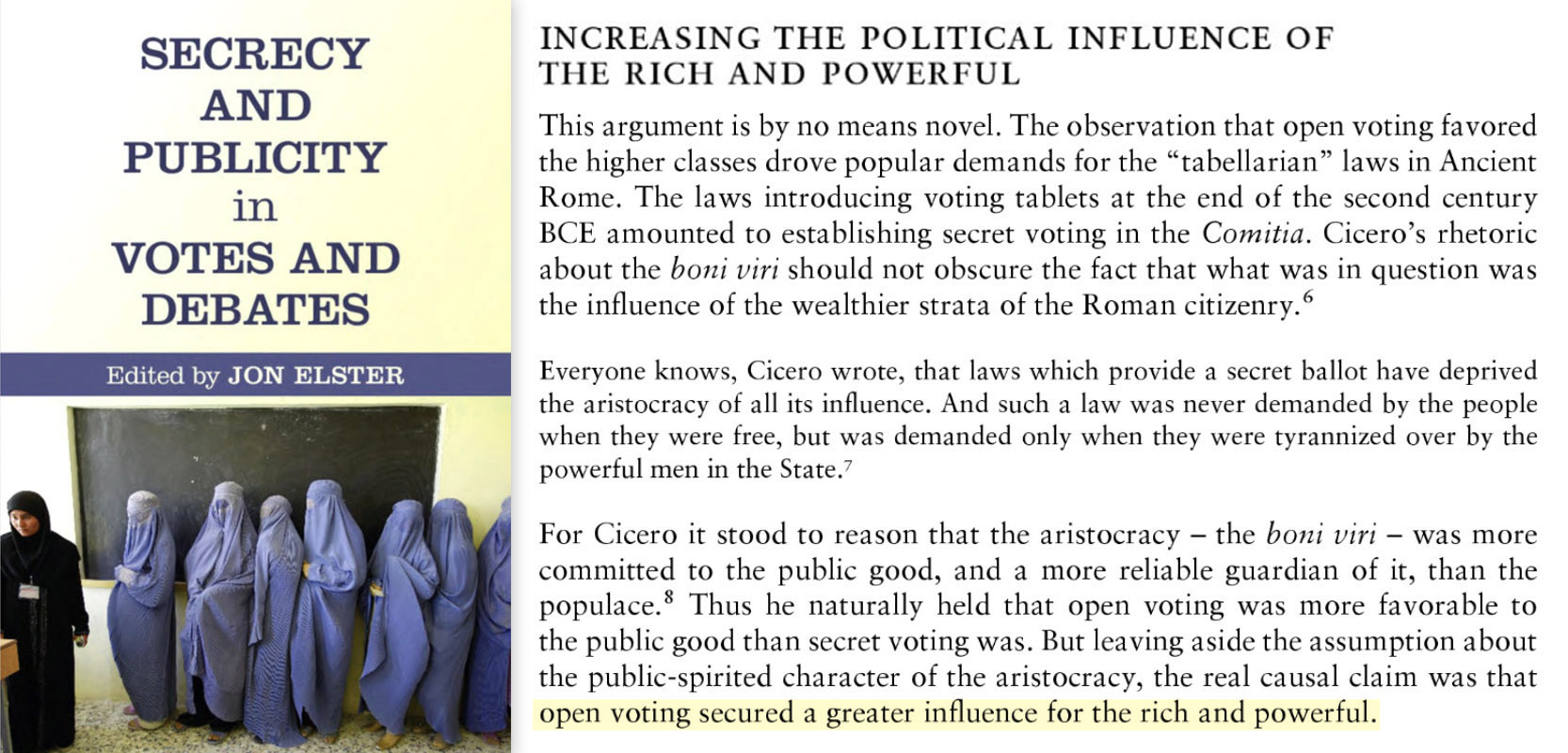

Bernard Manin 2015 - Open Voting Benefits Rich and Powerful

Some theorists claim that the secret ballot privatizes the vote. Actually, quite the opposite is true. It is only under public voting that the vote may effectively be employed for private gain. The secret ballot is an obstacle to such practice.Bernard Manin 2015

Some theorists claim that the secret ballot privatizes the vote. Actually, quite the opposite is true. It is only under public voting that the vote may effectively be employed for private gain. The secret ballot is an obstacle to such practice.Bernard Manin 2015

Secrecy and Publicity in Votes and Debates (Elster editor)

In the essay "Public Voting and Political Modernization" Buchstein writes “To Rudolf von Gneist (1816–95) – an outspoken German conservative critic of modern society – secret balloting was therefore a logical side effect of sociopolitical modernization. His resistance against secret balloting was [supposedly] part of his defense of the traditional feudal order, which he considered ‘more appropriate’ to mankind than industrial mass society. But one should not be fooled by the Gneist’s language: What Gneist had in mind politically was to intimidate the economically dependent masses on the country by the reactionary agrarian elite in Prussia, of which he was part.”Hubertus Buchstein 2015

In the essay "Public Voting and Political Modernization" Buchstein writes “To Rudolf von Gneist (1816–95) – an outspoken German conservative critic of modern society – secret balloting was therefore a logical side effect of sociopolitical modernization. His resistance against secret balloting was [supposedly] part of his defense of the traditional feudal order, which he considered ‘more appropriate’ to mankind than industrial mass society. But one should not be fooled by the Gneist’s language: What Gneist had in mind politically was to intimidate the economically dependent masses on the country by the reactionary agrarian elite in Prussia, of which he was part.”Hubertus Buchstein 2015

Secrecy and Publicity in Votes and Debates (Elster editor)

Checking the ways other people vote is likely to be driven by private concerns, not by a concern for the common good. Vote checking, then, is likely to be performed for the wrong reasons.Bernard Manin 2015

Checking the ways other people vote is likely to be driven by private concerns, not by a concern for the common good. Vote checking, then, is likely to be performed for the wrong reasons.Bernard Manin 2015

Secrecy and Publicity in Votes and Debates (Elster editor)

Ballot reform hence is part of the explanation for the turn-of-the century (1900) demise of partisanship.Susan Stokes & Thad Dunning 2010

Ballot reform hence is part of the explanation for the turn-of-the century (1900) demise of partisanship.Susan Stokes & Thad Dunning 2010

What Killed Vote Buying?

By secret voting alone could bribery and intimidation be stopped.Charles Seymour 1915

By secret voting alone could bribery and intimidation be stopped.Charles Seymour 1915

Electoral Reform - The Final Attack Upon Corruption

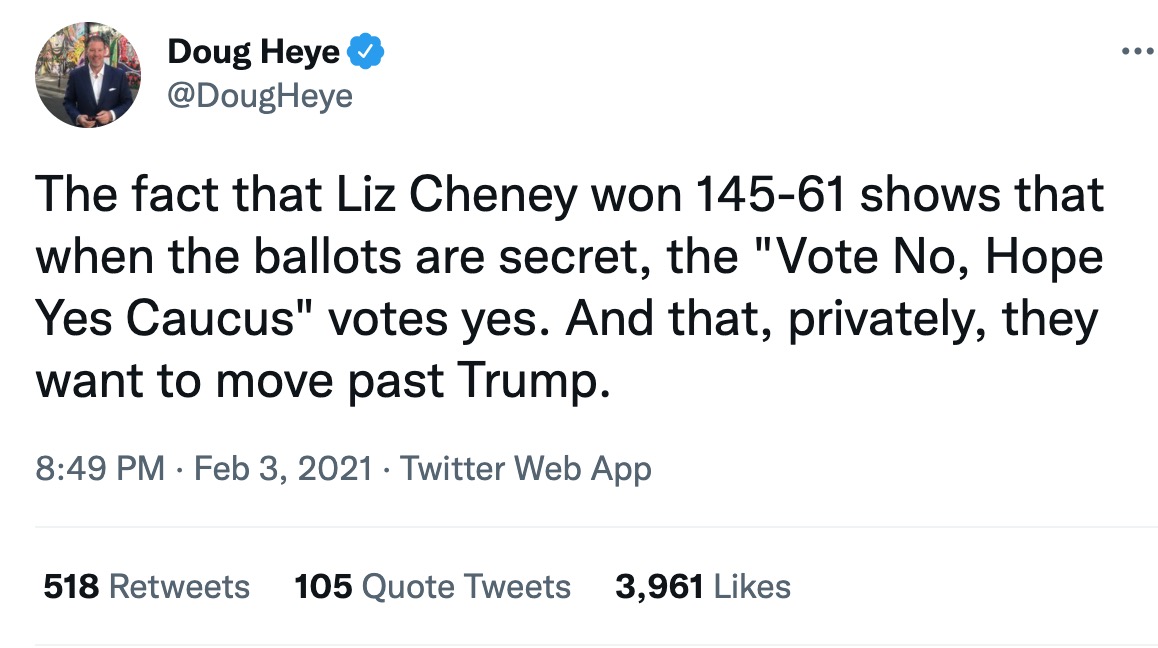

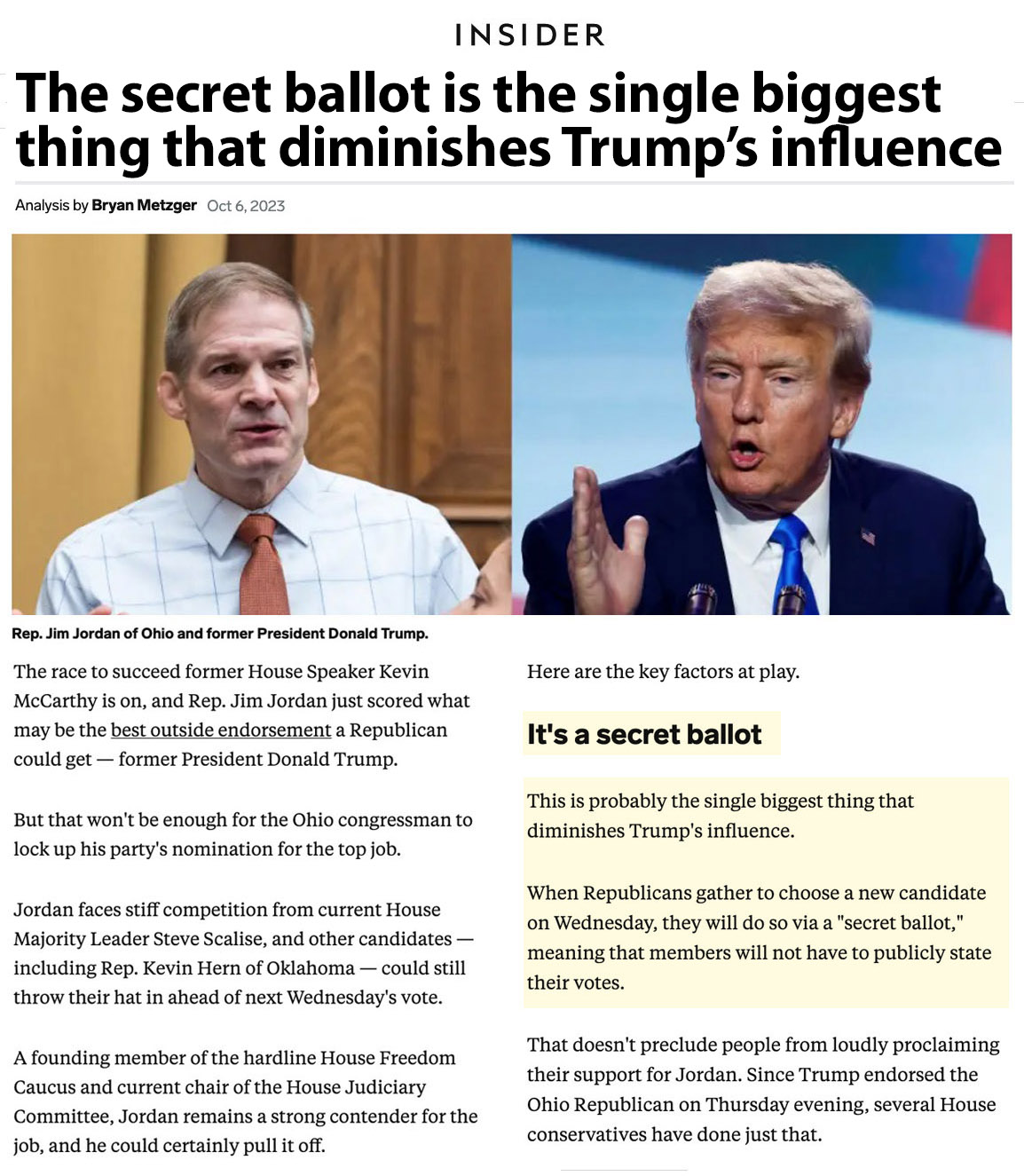

2021 Liz Cheney retains leadership role via secret ballot despite attacks on Trump

Labor racketeer Richard “Big Dick” Butler complained that “elections nowadays are sissy affairs. Nobody gets killed anymore and the ambulances and patrol wagons stay in their garages… [Before, the secret ballot] to be a challenger at the polls you had to be a nifty boxer.”Marie Alison Weiss 2013

Labor racketeer Richard “Big Dick” Butler complained that “elections nowadays are sissy affairs. Nobody gets killed anymore and the ambulances and patrol wagons stay in their garages… [Before, the secret ballot] to be a challenger at the polls you had to be a nifty boxer.”Marie Alison Weiss 2013

"A Plumb Craving for the Other Color"

LIncumbents most often have a direct access to state resources, which they can distribute to citizens in exchange for political support. Opposition parties rarely have access to financial resources that could in any way compete with the incumbents in vote buying efforts. The main problem with vote buying is that its effectiveness is often hard to measure or verify. As the ballot is cast in secret, vote buyers have little chances of knowing whether their vote buying effort actually had any significant effect on the voting behavior of the masses.Teemu S. Meriläinen 2012

LIncumbents most often have a direct access to state resources, which they can distribute to citizens in exchange for political support. Opposition parties rarely have access to financial resources that could in any way compete with the incumbents in vote buying efforts. The main problem with vote buying is that its effectiveness is often hard to measure or verify. As the ballot is cast in secret, vote buyers have little chances of knowing whether their vote buying effort actually had any significant effect on the voting behavior of the masses.Teemu S. Meriläinen 2012

Electoral Violence as a Side Product of Democratization in Africa

Soon after this sermon was preached, the election was held. Approaching the polls, I asked for a Union ticket, and was informed that none had been printed, and that it would be advisable to vote the secession ticket. I thought otherwise, and going to a desk, wrote out a Union ticket, and voted it amidst the frowns and suppressed murmurs of the judges and bystanders, and, as the result proved, I had the honour of depositing the only vote in favour of the Union which was polled in that precinct. I knew of many who were in favour of the Union, who were intimidated by threats, and by the odium attending it from voting at all. It was now dangerous to utter a word in favour of the Union. Many suspected of Union sentiments were lynched.John Hill Aughey 1863

Soon after this sermon was preached, the election was held. Approaching the polls, I asked for a Union ticket, and was informed that none had been printed, and that it would be advisable to vote the secession ticket. I thought otherwise, and going to a desk, wrote out a Union ticket, and voted it amidst the frowns and suppressed murmurs of the judges and bystanders, and, as the result proved, I had the honour of depositing the only vote in favour of the Union which was polled in that precinct. I knew of many who were in favour of the Union, who were intimidated by threats, and by the odium attending it from voting at all. It was now dangerous to utter a word in favour of the Union. Many suspected of Union sentiments were lynched.John Hill Aughey 1863

The Iron Furnace

In the middle decades of the nineteenth century [when votes were made openly], eighty-nine Americans were killed at the polls during Election Day riots.Jill Lepore 2008

In the middle decades of the nineteenth century [when votes were made openly], eighty-nine Americans were killed at the polls during Election Day riots.Jill Lepore 2008

Rock, Paper, Scissors

The formulation of the case against the ballot incorporated the self-interest of an aristocracy nervous about the potential impact of secret voting on the existing distribution of political power.Bruce Kinzer 2014

The formulation of the case against the ballot incorporated the self-interest of an aristocracy nervous about the potential impact of secret voting on the existing distribution of political power.Bruce Kinzer 2014

The Un-Englishness of the Secret Ballot

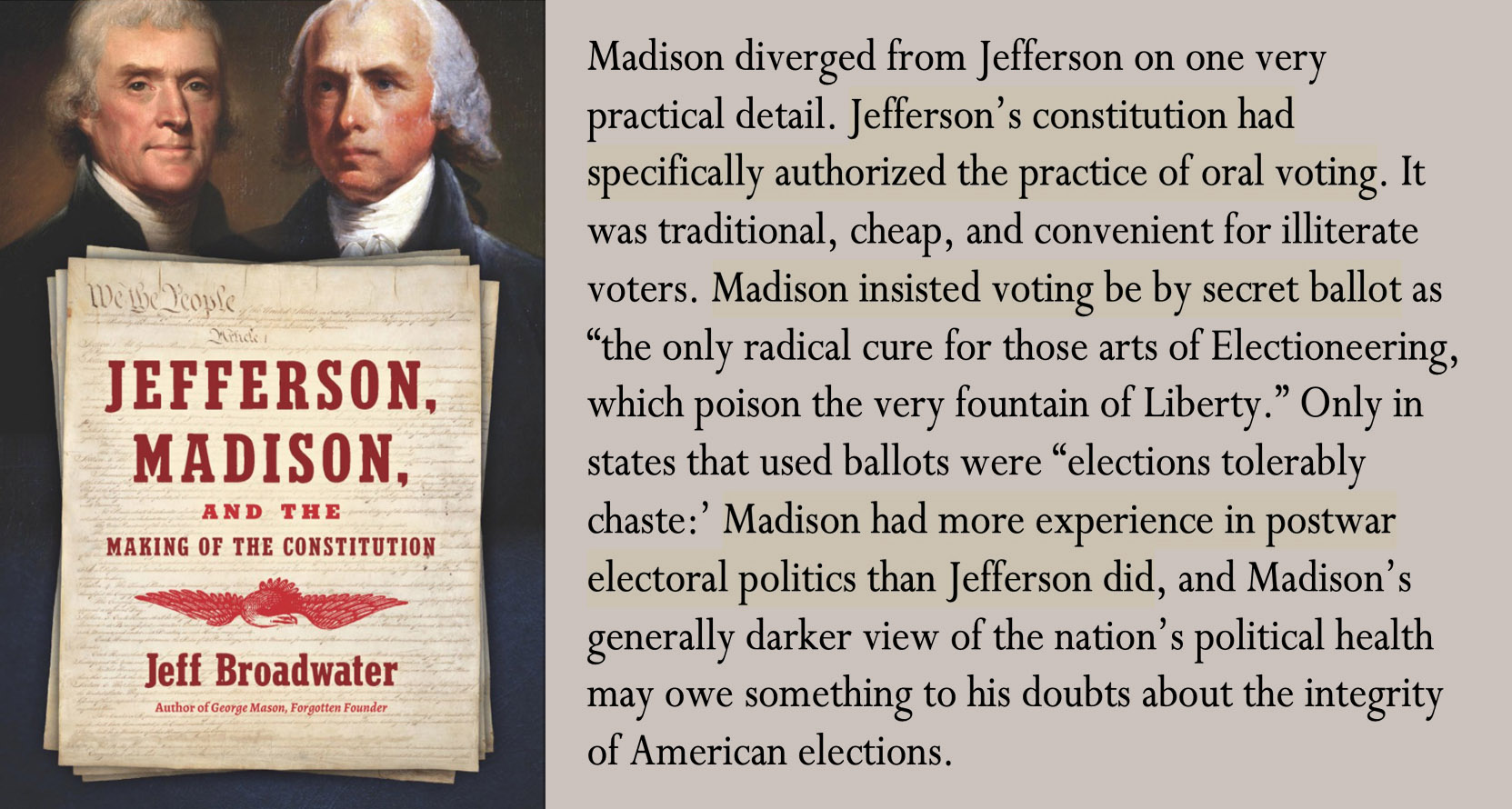

Jeff Broadwater 2019 - Madison vs. Jefferson

Madison diverged from Jefferson on one very practical detail. Jefferson’s constitution had specifically authorized the practice of oral voting. It was traditional, cheap, and convenient for illiterate voters. Madison insisted voting be by secret ballot as “the only radical cure for those arts of Electioneering, which poison the very fountain of Liberty.” Only in states that used ballots were “elections tolerably chaste:’ Madison had more experience in postwar electoral politics than Jefferson did, and Madison’s generally darker view of the nation’s political health may owe something to his doubts about the integrity of American elections.

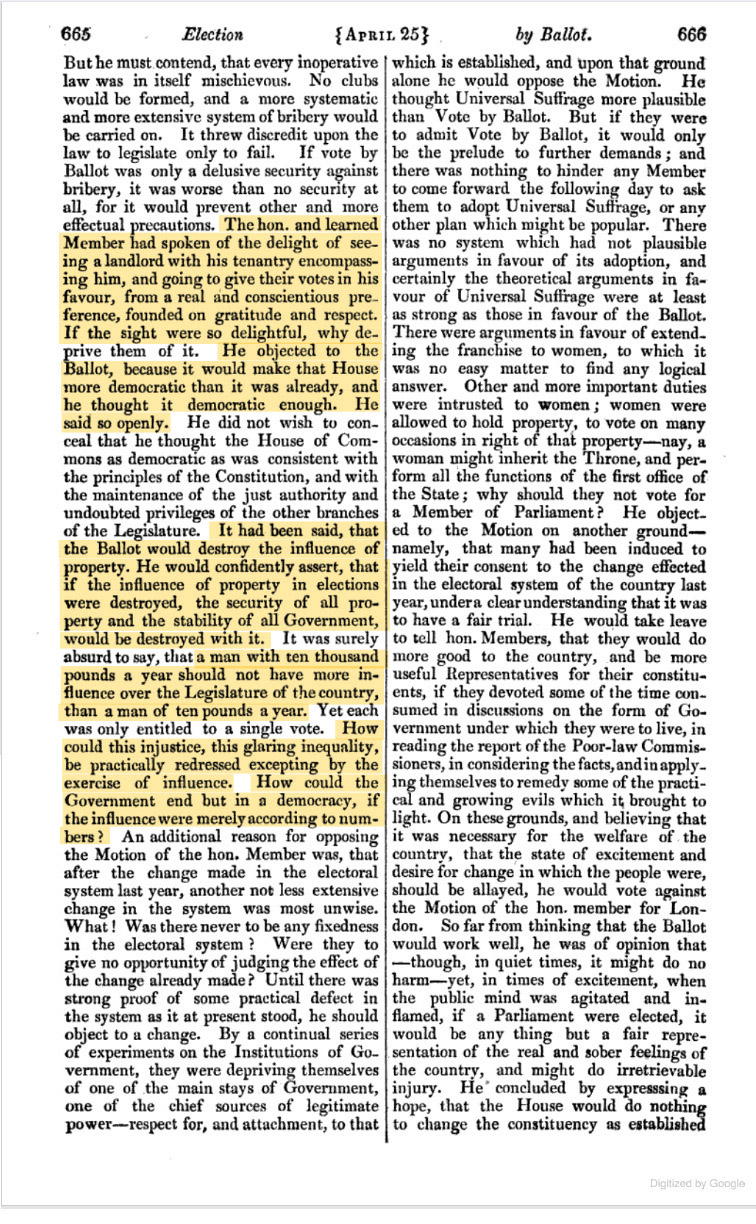

(I object) to the Ballot, because it would make that House more democratic than it is already, and (I think) it democratic enough.Sir Robert Peel 1833

(I object) to the Ballot, because it would make that House more democratic than it is already, and (I think) it democratic enough.Sir Robert Peel 1833

Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates*NOTE: The wealthy elite Robert Peel suggests that the problem with the secret ballot is that it would make the government more democratic. To elites, that was surely not a good thing. And while the argument likely has some merit, he does come off sounding a bit like Cicero on this topic.

The anonymous vote, a feature of the Australian ballot, was gradually adopted by all US states during the nineteenth century as a protection against intimidation, bribery, and voter harassment by political organizations and local factions (Fortier and Ornstein, 2002–2003). Denying would-be bribers and intimidators the chance to observe what voters actually did in the voting booth in effect undermined efforts to control vote outcomes. Bruce Cain 2014 (Stanford)

The anonymous vote, a feature of the Australian ballot, was gradually adopted by all US states during the nineteenth century as a protection against intimidation, bribery, and voter harassment by political organizations and local factions (Fortier and Ornstein, 2002–2003). Denying would-be bribers and intimidators the chance to observe what voters actually did in the voting booth in effect undermined efforts to control vote outcomes. Bruce Cain 2014 (Stanford)

Democracy More or Less

Although open threats against Roman voters seem to have been exceptional, the necessity to vote openly, under the watchful eyes of their superiors, could not fail to hamper the voters’ freedom of choice. A voter might be reluctant to offend not just his patron, but his landlord, or his military commander… The change brought about by the ballot laws must then have been quite significant. Modern scholars have stressed the popular and liberating nature of this legislation, and it has even been described as a manifestation of “a much more genuine popular movement than the Gracchan legislation itself.”Alexander Yakobson 1995

Although open threats against Roman voters seem to have been exceptional, the necessity to vote openly, under the watchful eyes of their superiors, could not fail to hamper the voters’ freedom of choice. A voter might be reluctant to offend not just his patron, but his landlord, or his military commander… The change brought about by the ballot laws must then have been quite significant. Modern scholars have stressed the popular and liberating nature of this legislation, and it has even been described as a manifestation of “a much more genuine popular movement than the Gracchan legislation itself.”Alexander Yakobson 1995

The Secret Ballot and its Effects in the Late Roman Republic

It has been suggested that the ballot laws did not fully ensure the effective secrecy of the voting; the nobles found ways to circumvent the legislation and thus protect their ascendancy.Alexander Yakobson 1995

It has been suggested that the ballot laws did not fully ensure the effective secrecy of the voting; the nobles found ways to circumvent the legislation and thus protect their ascendancy.Alexander Yakobson 1995

The Secret Ballot and its Effects in the Late Roman Republic

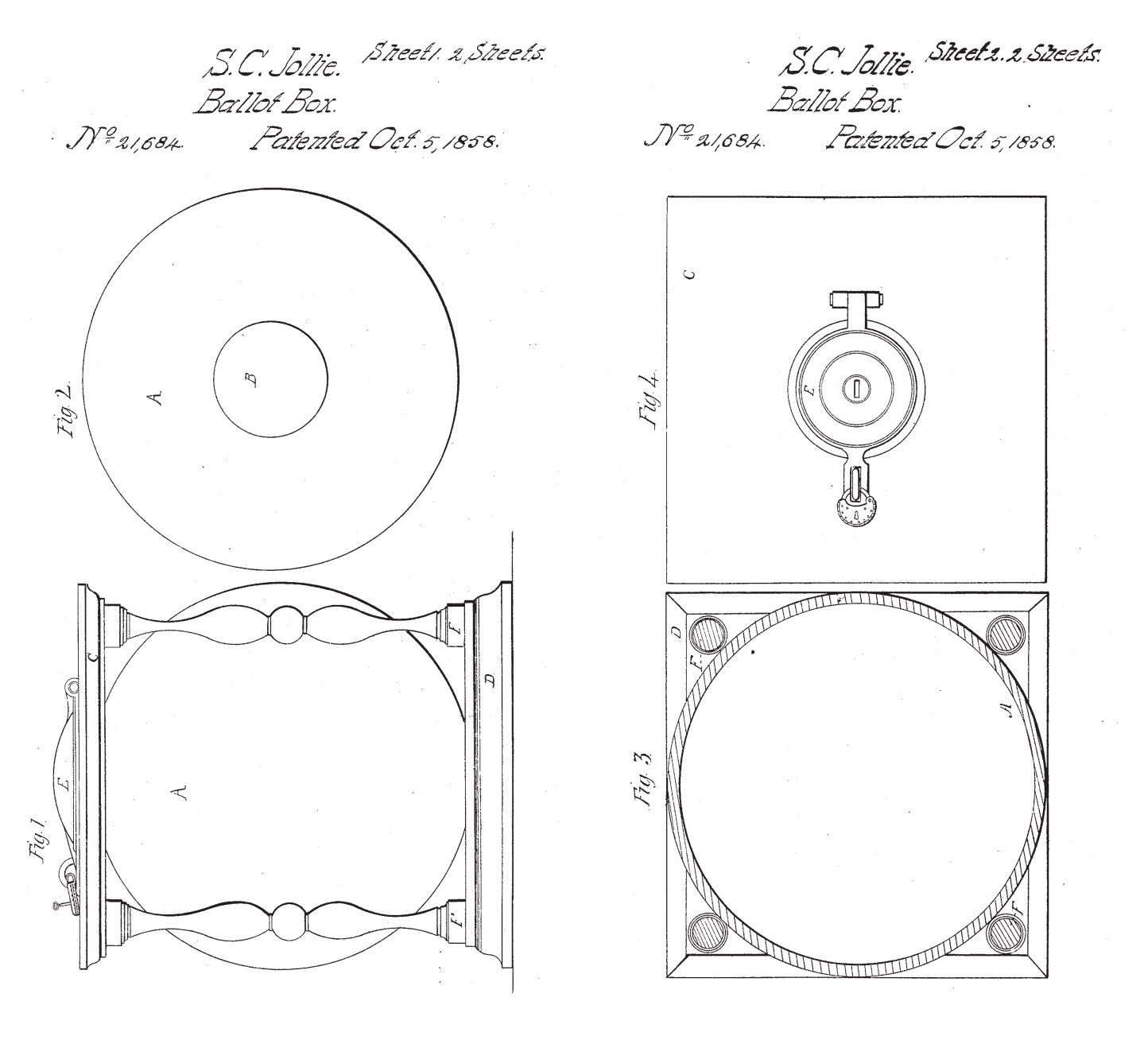

Samuel Jollie Patent Application for Transparent Voting Box 1858

Because most democracies use a secret ballot, citizens can accept the money but vote for whichever candidate they prefer even if their preferred candidate did not offer similar gifts.Ari Pradhanawati, George Towar Ikbal Tawakkal & Andrew D. Garner 2018

Because most democracies use a secret ballot, citizens can accept the money but vote for whichever candidate they prefer even if their preferred candidate did not offer similar gifts.Ari Pradhanawati, George Towar Ikbal Tawakkal & Andrew D. Garner 2018

Age of Voting their Conscience

The general impression of the new system was positive, with Childers among those rejoicing that the secret ballot had proved ‘thoroughly workable’. In contrast with the unruly behaviour which had often marred previous elections, seasoned observers declared that ‘they never saw a contested election in which less intoxicating liquor was drunk’ and there were no allegations of bribery or other corrupt practices. So quiet and orderly was the town that ‘it hardly seemed like an election’.Kathryn Rix 2013

The general impression of the new system was positive, with Childers among those rejoicing that the secret ballot had proved ‘thoroughly workable’. In contrast with the unruly behaviour which had often marred previous elections, seasoned observers declared that ‘they never saw a contested election in which less intoxicating liquor was drunk’ and there were no allegations of bribery or other corrupt practices. So quiet and orderly was the town that ‘it hardly seemed like an election’.Kathryn Rix 2013

The First Secret Ballot in Britain

Before the introduction of the secret or Australian ballot following the vote-buying scandals of 1888, the parties printed the ballots, “slip tickets,’ in party-coordinated lengths and colors. (“Big Tim” Sullivan of Tammany Hall perfumed his tickets, “so that they might be tracked to the ballot box by scent, as well as by size, shape, and color.”) Inquisitive party hacks manned the polling places. Like the party snoops monitoring East German plebiscites, they knew who voted and how, and who didn’t vote. Workingmen could vote – but in company towns like Scranton, Pennsylvania, they had to vote right. “Why do you say the poor men here have not the right of suffrage?” the chairman of a House committee investigating the effects of the long depression of 1873-79 asked a Scranton man. “I do not,” he replied, “consider that they have the right of suffrage when a foreman stands at his window and says, as a poor man goes up to cast his ballot, ‘There is another of those God-damned short tickets going in; we will have to see that fellow’; and when, a day or two previous to the election, another man is told that the best thing he can do is to keep his mouth closed. In such cases men have the right of suffrage only in name, not in fact.”Jack Beatty 2008

Before the introduction of the secret or Australian ballot following the vote-buying scandals of 1888, the parties printed the ballots, “slip tickets,’ in party-coordinated lengths and colors. (“Big Tim” Sullivan of Tammany Hall perfumed his tickets, “so that they might be tracked to the ballot box by scent, as well as by size, shape, and color.”) Inquisitive party hacks manned the polling places. Like the party snoops monitoring East German plebiscites, they knew who voted and how, and who didn’t vote. Workingmen could vote – but in company towns like Scranton, Pennsylvania, they had to vote right. “Why do you say the poor men here have not the right of suffrage?” the chairman of a House committee investigating the effects of the long depression of 1873-79 asked a Scranton man. “I do not,” he replied, “consider that they have the right of suffrage when a foreman stands at his window and says, as a poor man goes up to cast his ballot, ‘There is another of those God-damned short tickets going in; we will have to see that fellow’; and when, a day or two previous to the election, another man is told that the best thing he can do is to keep his mouth closed. In such cases men have the right of suffrage only in name, not in fact.”Jack Beatty 2008

Age of Betrayal - The Triumph of Money in America, 1865-1900

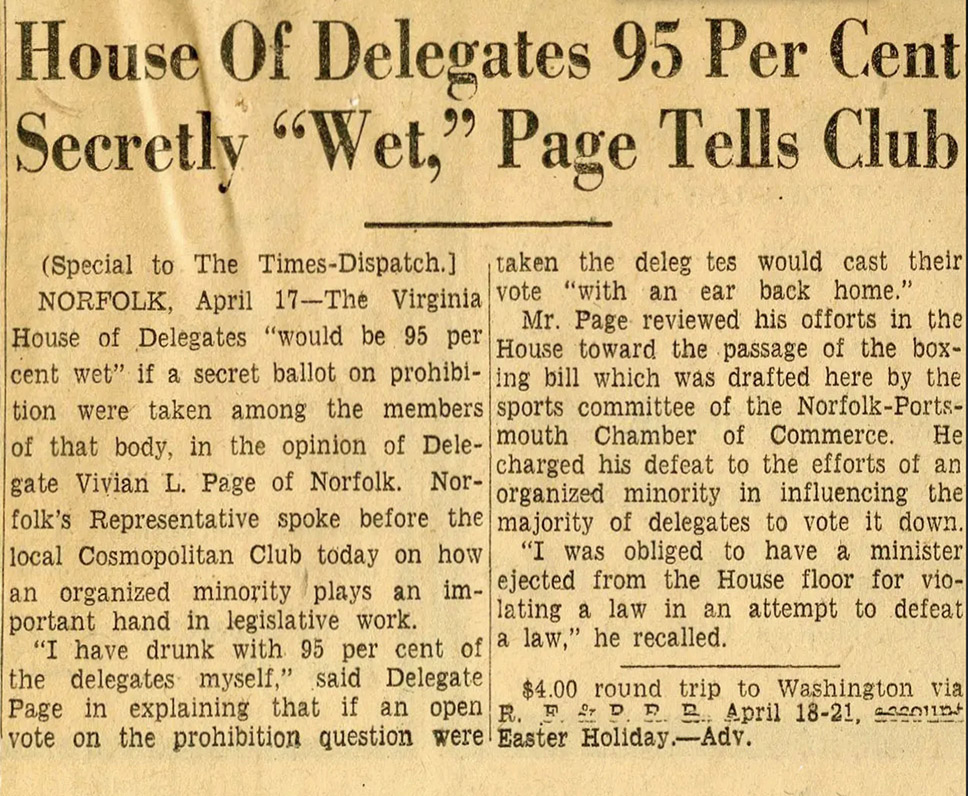

Richmond Times-Dispatch 1930 - House of Delegates 95 Per Cent Secretly ‘Wet,’ Page tells Club

House Of Delegates 95 Per Cent Secretly “Wet,” Page Tells Club (Special to The Times-Dispatch.) NORFOLK, April 17—The Virginia House of Delegates “would be 95 per cent wet” if a secret ballot on prohibition were taken among the members of that body, in the opinion of Delegate Vivian L. Page of Norfolk. Norfolk’s Representative spoke before the local Cosmopolitan Club today on how an organized minority plays an important hand in legislative work. “I have drunk with 95 per cent of the delegates myself,” said Delegate Page in explaining that if an open vote on the prohibition question were taken the delegates would cast their vote “with an ear back home.” Mr. Page reviewed his efforts in the House toward the passage of the boxing bill which was drafted here by the sports committee of the Norfolk-Portsmouth Chamber of Commerce. He charged his defeat to the efforts of an organized minority in influencing the majority of delegates to vote it down. “I was obliged to have a minister ejected from the House floor for violating a law in an attempt to defeat a law,” he recalled. Richmond Times-Dispatch, Apr. 18, 1930.

If an open vote market [for public votes] exists, government policy will be dictated by high income groups.Anthony Downs 1957

If an open vote market [for public votes] exists, government policy will be dictated by high income groups.Anthony Downs 1957

An Economic Theory of Democracy*NOTE: This citation comes at the end of a brilliant analyisis by Downs, the full text of which is here: Before answering these questions, we must first examine the peculiar character of the value of voting to an individual. In any large-scale election, a rational voter knows that the probability that his vote will be in any way decisive is very small indeed. Given the behavior of all others, his vote is thus of almost no value to him at all, no matter how important it is to him that party P beat party Q. Consequently he will be willing to sell his vote for a very low price if vote-selling is legal, since money is definitely of value to him. In other words, every rational voter has a low reservation price on his vote. Nevertheless, this does not mean votes would be cheap in an uncontrolled market; their price depends upon demand as well as supply. To explore this matter further, let us assume for the moment that (1) there is no legal restraint on the purchase or sale of votes and (2 ) some kind of negotiable vote certificates are printed up and distributed one to each voter before each election. What will happen? No one voter has much political power—that is why there is a low reservation price. But any voter who can buy up a large number of votes can strongly influence the government’s policy in any area of interest to him. As a result, those desiring such power and possessed of vote-buying capital funds will form a demand for votes. Others not so desirous, or not so endowed with funds, will act as vote-suppliers. It is even possible that there will be keen competition among vote-demanders, so that the price of votes will be driven well above the reservation price of a majority of citizens. If this happens, most low-income citizens will not be able to afford to be buyers but will instead become sellers. Thus no matter which of the competitors finally accumulates enough votes to control government policy, the winner will almost always be a possessor of high income or large capital. In short, if an open vote market exists, government policy will be dictated by high income groups, even if there is severe competition within these groups for dominance over specific policies.

Secrecy, in short, is not disappearing. It remains at the heart of democracy, certainly as it has been practiced in the United States since the adoption of the Australian or “secret” ballot in the 1890s. There is a plausible argument – the English political thinker John Stuart Mill presented it in the mid-nineteenth century – that democracy works better if citizens are publicly held accountable for their votes. But this argument lost out to the concern that public voting subjected relatively powerless individuals to threat, arm-twisting, or bribery by the powerful (notably, employees were vulnerable to coercion by their employers). In designing democracy, a realistic assessment of the consequences of unequal power for the independence of individual voters overcame the conceptual appeal of openness.Michael Schudson

Secrecy, in short, is not disappearing. It remains at the heart of democracy, certainly as it has been practiced in the United States since the adoption of the Australian or “secret” ballot in the 1890s. There is a plausible argument – the English political thinker John Stuart Mill presented it in the mid-nineteenth century – that democracy works better if citizens are publicly held accountable for their votes. But this argument lost out to the concern that public voting subjected relatively powerless individuals to threat, arm-twisting, or bribery by the powerful (notably, employees were vulnerable to coercion by their employers). In designing democracy, a realistic assessment of the consequences of unequal power for the independence of individual voters overcame the conceptual appeal of openness.Michael Schudson

Rise of Right to Know

It is true that in many situations an indigent vote-seller and a wealthy vote-buyer would both gain if the former could sell his vote to the latter. However, in almost every such instance, their gain is someone else’s loss. Anthony Downs 1957

It is true that in many situations an indigent vote-seller and a wealthy vote-buyer would both gain if the former could sell his vote to the latter. However, in almost every such instance, their gain is someone else’s loss. Anthony Downs 1957

An Economic Theory of Democracy

Some… predicted that the introduction of the secret ballot would lead to the end of the established church, the abolition of the House of Lords, and the end of the monarchy.Tom Theuns 2017