The 1973 Jumbotrons

How sunshine benefits the powerful

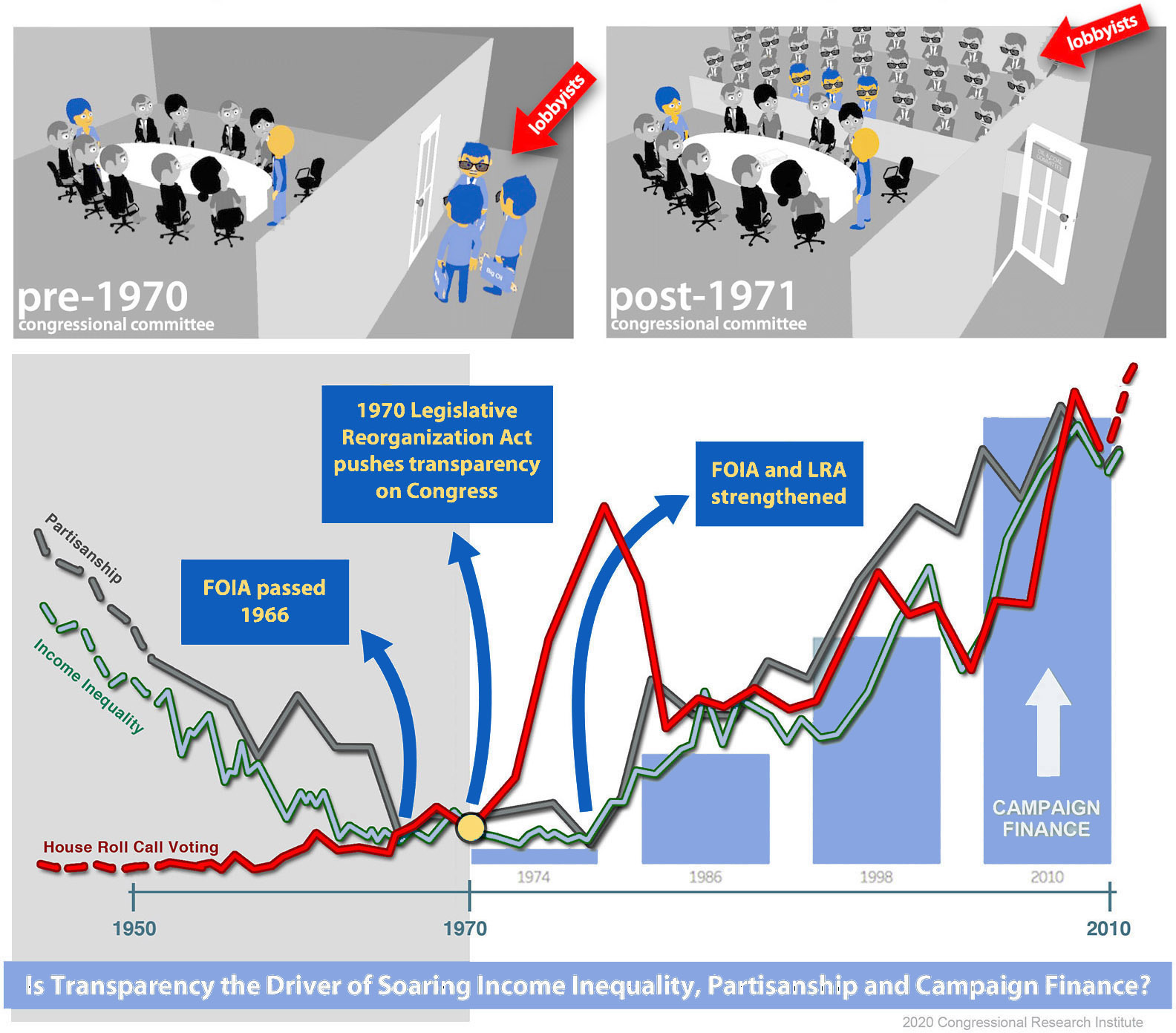

On January 3rd, 1971, the US Congress switched from being one of the most closed institutions in history to one of the most open. Congressional voting and meetings that were once secret were thrust open in a wave of ‘democratic’ transparency. No evidence has ever been offered to support this change, and there is now ample evidence to suggest that these actions overwhelmingly benefit lobbyists and the powerful.

By James D’Angelo, David King, Brent Ranalli – September 2, 2020

The Electronic Voting System in the House of Representatives was used for the first time on January 23, 1973 – 87 years after the first proposal to use an automated system to record votes was introduced.Jacob Straus 2008

Electronic Voting System in the House

The Voting Boards

In 1973 a set of four jumbotron-sized electronic boards were hung on the walls of the House galleries just above the Speaker’s head. As members voted on the floor, their names were broadcast above in bright lights. Next to each name was a red dot if they voted ‘no’, a green dot if they voted ‘yes’ and a yellow dot if they were still undecided.

Because of this, for the first time in history, any legislator (or lobbyist) could get a second-by-second, rolling tally of all member’s votes by just checking “the board.” Importantly, these boards removed all signaling costs between members, lobbyists and others, allowing for broad unspoken arm-twisting of all members on each vote. As such, the boards, themselves, are likely a significant source of increasing partisanship and corruption.

Still, few citizens are aware of the existence of these jumbotrons. This is because as soon as the voting ends (and the member’s votes are published), the boards are covered in brocade cloth. As a result, images of these 12-foot square monstrosities have yet to appear in textbooks and are never exposed during the Chamber’s most public events like the Presidential State of the Union.

Still, their exclusion from textbooks does not diminish their importance on history. From the day the boards were installed, 50 years ago, the members (and other interested parties) watch them with the fervor one might follow the rolling ticker of the stock market or the final out of the World Series.

The Changes

1. Lobbyists Get the Upper Hand

It is an understatement to say that this massive increase in transparency brought about dramatic changes all over Washington DC. Overnight, the power dynamic between lobbyist and legislator flipped. Where once the congressman held all the cards in every meeting, the tenor changed completely. The lobbyist could suddenly wield credible threats and strike deals based on verifiable votes. This newfound accountability changed the political landscape by allowing ‘insider-trading-style access’ to any wealthy interest around the world. This benefit to lobbyists and the powerful has been recognized by hundreds of scholars.

Immediately on the heels of the sunshine reforms, the careers of lobbyists flourished, and as scholar John Kingdon suggests, ‘members felt more and more harassed... more pressure from single interest groups...(and) more need to raise campaign money.’ Just after retiring from Congress, Senator Bumpers underlined this same sentiment:

In the 1970’s national associations by the dozens were setting up shop in Washington, right down to the beekeepers and mohair producers, and with them came a new threat to the integrity of the legislative process: “single issue” politics. These groups developed very harsh methods of dealing with those who crossed them. Suddenly, every vote began to have political consequences...We (Senators) have all come to reflexively calculate on every vote, significant or insignificant, (1) what 30-second television spot our next opponent can make of it, (2) the impact it could have on contributions, and (3) what interest group it might inflame or please.

Senator Dale Bumpers 1999

How Sunshine Harmed Congress

In the LRA’s wake, K-Street grew exponentially as special interests were able to participate directly in the drafting of legislation that would eventually become law. Indeed, the entire growth of the lobbying industry is highly correlated to the rise in transparency. And since 1970, money invested in lobbying Congress yields some of the world’s highest returns on investment (figure below). Equally important, perhaps, is that during this same period, the public’s trust in Congress has been in near free fall.

2. Party Leaders Get the Upper Hand

A strikingly similar transformation (and likely just as powerful an influence on legislation) also occurred between the members themselves, centralizing power into the hands of the few. With the increased accountability provided by the LRA, party leaders can now intimidate or cajole the rank-and-file members, turning every vote into a game of carrots and sticks. As a result, coveted committee seats, favorable hearings and other congressional perks are given only to those members who vote consistently with leadership. And as dozens of scholars have noted the increased sunshine drives partisanship.

Caught in the lurch, freshmen legislators know that if they want their cherished legislation to reach the floor for a vote, they have to play ball. This power dynamic is likely the principal cause of soaring partisanship as all voting is dictated by fewer and fewer voices, and it appears to be a powerful driver of campaign finace as well, as committee chairs consistently raise far more money than other members.

Nowhere is this rise in power seen more clearly than with the Speaker of the House. Throughout history, the Speaker has wielded power, but open voting increased this power significantly. With significant control over the legislative calendar, committee assignments and the contents of omnibus bills (an obfuscating device that also correlates strongly with increased transparency), the Speaker applies these same newfound accountability measures to sway all legislation with simple threats and intra-house perks. Under the strong-armed whip/majority leader Tom DeLay (1995-2005), over 50% of the Republican procedural and amendment votes were unanimous, which means that on most votes, not one Republican member dared step out of line.

NOTE: Overlooked by most scholars, intimidation (arm-twisting) appears to be the predominant force used by both interest groups (like the NRA) and members of Congress to influence legislators. It seems likely to effect legislation more than the common scapegoat of campaign finance. Unlike campaign finance, intimidation is often vastly less expensive and one threat can directly influence all members of Congress (even inadvertently). More importantly, many forms of intimidation are legal, so even soft-spoken Speakers, like John Boehner, make their ultimatums comfortably in front of the rolling cameras of the press.

3. The President Gets the Upper Hand

This same pattern can be reapplied endlessly. A more accountable Congress yields increased power to anyone who can apply pressure via threats or perks. This includes police unions, the Tea Party and most notably during the recent impeachmeant hearing, the President.

Even on regular legislation this redistribution of power, upwards to the executive is clear. During close votes on important bills, members of Congress receive calls from the President pressuring them to rethink their position. For example, on 2am on November 22, 2003 – while the House vote was still open – George W Bush made such calls from Air Force 1, to push Republican representatives to reverse their votes on Medicare Part D, one of the largest government expenditures in history. In the background, Barney Frank could be heard on the floor shouting “stop the arm-twisting,” a pressured congresswoman was crying, other members left the chamber to hide from the threats, and months later it was determined there were bribery attempts, threats and suffocating controls imposed by the rules committee.

When voting is secret, members are free to vote their conscience. In Congress, this means that secret voting eliminates intimidation and bribery. Secrecy (just as it worked in 1890 with the secret ballot) checks the powers of all special interests, including the Speaker, the President and the enormous partisan powers of party and PACs. By opening the vote, the executive branch gains enormous power over the legislature, and this becomes especially dangerous when the sitting President (as George Bush was in 2003) is seeking re-election.

4. Constituents Lose Ground

(Members grow to) feel more accountable to some constituents than to others because the support of some constituents is more important to them than the support of others.Richard Fenno 1976

House Members in their Constituencies

While special interests and others inside government gain enormous powers with the direct accountability provided by transparency, the reverse is true for constituents. Indeed, legislation and legislators’ attention are zero-sum games. As special interests and others can now directly threaten and mandate members, hence demanding more time, attention and legislation, constituents (who cannot directly threaten members) lose ground. This happens even inside Congress as even the members with the best intentions, are compelled by leadership to vote along party lines.

These outside pressures can be seen in the recommended schedule below. As shown in the image, a member is likely to spend 5 hours a day pleading with wealthy special interests, 2 hours a day inside committees under the pressures of the Speaker and other intra-governmental special interests and just 1 to 2 hours a day chatting with ‘constituents’ (more on them later).

Importantly, none of these call-time conversations are made transparent, and there is likely no way to open them to increased public scrutiny. This is because members of Congress aren’t prisoners, as such they could easily interact with special interests anywhere, at any time (in bars, the gym, their house, by phone, in bathrooms, etc). Nevertheless, these conversations are essential to the existence of a legislator, and they dictate policy, bend legislation, and influence all of the thousands of budget items under congressional jurisdiction.

The trouble is, because of the increased accountability provided by open voting, they are no longer conversations in which the representative has the upper hand. And with thousands of budget items a year and thousands of calls/meetings being made, this begins to resemble a form of ‘legislation for sale.’ Worse, as all budgeting is by its very nature subjective and slippery (more on this later), untraceable corruption can exist in each of the thousands of budget items, even under strict transparency regimes (and likely because of strict transparency regimes).

‘Call time’ is not time spent calling your family, or think tank experts, or ordinary constituents. It’s time spent calling donors. Strategic outreach is, of course, also time you can spend with donors, and if your constituent visits include constituents who are donors, then all the better!Ezra Klein 2013

The Washington Post

But there’s hope right? 1 to 2 hours a day are spent with constituents. But who are these constituents? Many of them are brought in by the same lobbying groups that are on the phone with members just a few hours before, pushing the same biased agenda. And the rest of them are hardly average constituents. Indeed, there is little that political scientists agree on more than the notion that general constituents do not follow the actions of Congress, but lobbyists do.

And like most interest groups, the few constituents that show up to pester legislators often have specific agendas they are pushing, and are likely to represent just a tiny fraction of the member’s jurisdiction. Indeed, outside of holding a well-attended vote on each and every issue, it appears impossible for a member to gauge the true intentions of their constituency (even expensive polling efforts are proving more faulty each year). So as members spend more and more time with narrow interests, they have less and less time to ponder the repercussions on the greater constituency or even the nation’s common good.

How Transparency Benefits the Powerful

The question arises (whether)...transparency is either conducive to more corruption or, at least, to corruption taking forms that are more detrimental to efficiency or equity.Albert Breton 2007

The Economics of Transparency in Politics

Ironically, the ability for interest groups (and others) to reward or punish legislators, relies entirely on high levels of transparency and accountability. As such, the more open a legislature, the easier the work of a special interest becomes. In just seconds, Big Pharma and Big Oil can scan the congressional record (tens of millions of pages), searching for just a handful of key terms that affect their narrow industry. As a result, they can distill this seemingly impossible amount of information into just a dozen or so key lines of legislation. Then, they can draft legislation, incentivize a congressman to drop it into the hopper, and precisely monitor the individual votes and actions of each legislator as the legislation moves forward. If any congressman steps out of line (at any step of the legislative process), these pressure groups get rough, going after that legislator with force.

While this process is much more direct than voting, it is hardly democratic. Indeed, it appears that increased transparency lays the foundation for oligarchy, as the greater the resources the special interest has, the more accountability they can unleash. So while the NRA or Big Oil can twist arms and change votes, these same levers of power are not available to the average constituent. Indeed, the average constituent is the polar opposite of a powerful special interest in two fundamental ways, and these differences are highlighted by the two following problems:

1. Transparency Benefits Special Interests

Unlike special interests, the average constituent is not likely focused only on one narrow issue. Instead, constituents are concerned about corruption in any aspect of government and therefore maintain broad interests throughout. As such, a constituent is better described as a general interest. But, having a broad set of interests results in a marked disadvantage when it comes to monitoring Congress. Indeed, unlike the NRA or Big Oil, general interests are unable to quickly scan legislation by searching for just a handful of key terms. Instead, a vigilant constituent is burdened with millions and millions of pages of hearings, amendments, summaries and legislation as each line could be the source for corruption.

See our page dedicated to this topic

See our page dedicated to this topic

More importantly, like a Facebook post, the congressional record is hardly a source of reliable or complete information. By their very nature, even the most transparent hearings and debates include omissions, grandstanding and political bias. And there are those who suggest that the more transparent the proceeding, the more of these problems there are (quote below). As such, constituents are faced with the Brobdingnagian task of not just reading the dense legalese, but also scrutinizing each of the millions of pages with an eye for inaccuracies, bias and omission (wherein each line could take months or more to substantiate).

Disclosure also induces policymakers to distort the process of information gathering and evaluation. In contrast, when no information can be disclosed, the government has no incentive to manipulate information. Secrecy is therefore effective at protecting the integrity of the decision-making process.– Patacconi, Vikander 2013

Further, each of the thousands of budget numbers are impossible to verify, as they can only be, at best, subjective. It is impossible to prove that the allotted $372 million for the Justice of the Interior is appropriate amount when a number twice as high or half as much could be argued and supported by the same congressional budgeting process. This absolute subjectivity means that it is likely impossible for constituents (even those with extensive resources and time) to comb through legislation for corruption. While absurd, this claim is well supported by the notion that scholars insist that corruption is endemic and pervasive but very little corruption is actually found or prosecuted. This can clearly lead to hopelessness as evidenced by the remarkably little attention citizens pay to congressional voting and legislative actions. It appears, therefore, that legislative transparency greatly benefits special interests while, at the same time, only overwhelms and confuses constituents. Indeed studies show that excessive information, dumped wholesale on constituents, clouds understanding and distorts decision-making. Political scientist, Francis Fukuyama expresses this informational asymmetry clearly:

The typical American solution to perceived government dysfunction has been to try to expand democratic participation and transparency. Almost all of these reforms failed in their objectives of creating higher levels of accountable government. The reason is that democratic publics are not in fact able by background or temperament to make large numbers of complex public policy choices; what has filled the void are well-organized groups of activists who are unrepresentative of the public as a whole. The obvious solution to this problem would be to roll back some of the would-be democratizing reforms, but no one dares suggest that what the country needs is a bit less participation and transparency.– Francis Fukuyama 2014 - Political Order and Political Decay

2. Accountability Benefits the Wealthy & Powerful

A donor who gives $100,000 gets a lot more free speech than the assembly-line worker.

Sen. Bumpers 1999

How Sunshine Harmed Congress

It doesn’t take much imagination to realize that special interests and other powerful groups can hold members of Congress accountable. The trouble is, few if any, scholars seem to acknowledge this. In perhaps the greatest of oversights, the word ‘accountability’ is mistakenly associated exclusively with the people (who, ironically, have the least power to use it). This strange paradox is manifest even in Apple’s dictionary definition of ‘accountable.’

Indeed, as we’ve suggested, accountability is strongly dependent on wealth and power. While average constituents are limited to just their vote, special interests can apply direct pressure at any time of the year via the media or with finance. Even large constituent groups (i.e. the 99%ers) lack the resources to bribe or intimidate legislators in the same fashion as Big Oil, the NRA and others. This is confirmed by various angles of research which suggest that voting is a remarkably diluted, imprecise and indirect tool, and citizen-based accountability is exceedingly difficult and rare.

See our page dedicated to this topic

See our page dedicated to this topic

This massive asymmetry of power can also be intuited from the ease of access given to these powerful groups. While individuals may struggle for even a few minutes of time with their representatives, special interests and large donators can expect to be on the receiving end of members’ phone calls and letters. And while voters have very little incentive to spend the entire year scouring the congressional record partly because they have little ability to hold member’s accountable, the opposite is true for large corporations who pour millions into aggressive lobbying campaigns confident that their efforts can produce billions of dollars worth of tax exemptions or subsidies. This means that increased accountability measures should always benefit the wealthy and harm the middle class and the poor.

The end result of all this lobbying...is a government so in hock to special interests that it has little money left to meet the general interest...the utilities doled out more than $10 million in campaign contributions to insert a provision that will end up saving them $19 billion.– Alex Raskin, LA Times 1994

As seen, the transparency and accountability problems are intimately intertwined. Because of increased transparency, special interests can quickly gather all the information they need (information asymmetry), and with that information they are uniquely able to hold members accountable (asymmetry of power). Each problem, in turn, strengthens the other and together they suggest a clear path to the oligarchy suggested by the New Yorker’s coverage of the work of Gilens and Page. More importantly, these two problems appear to be fatal flaws with two of the most fundamentally misunderstood and poorly analyzed policy agenda points of the last hundred years. It is shocking to consider that the wholesale the embrace of increased transparency appears to be completely unsupported by evidence, research or data. And indeed (as Fukuyama mentions above), it is hard to imagine a political reform that calls for less transparency. So instead of diminishing the problem, activists and scholars are insisting on measures that would appear to increase corruption, partisanship, campaign finance and intimidation. As a result we would expect problems like the debt, income inequality, and climate change to soar in their wake.

Sources: CQ Quarterly analysis of congressional campaign finance, Piketty & Saez's research on inequality, McCarty's work on partisanship, and public roll call data.